2021 Year in Review

Open Source China Research, Best of the Newsletter and Podcast, What's Next for ChinaTalk

Open Source Chinese Government Research

Earlier this year, my favorite college professor passed away. Donald Kagan was a historian of Ancient Greece and lifechanging around a seminar table.

His courses would cover around thirty years of history. Each week, he would give two students simple prompts for five page papers that were circulated to the rest of the class and served as the basis for discussion. After spending the first fifteen minutes querying the papers’ authors, he would cold-call the room, incorporating responses while guiding the discussion. He tried to limit seminar size to 15 (the Spartans’ preferred number for common meals), though inevitably there would be 25+ crowded in.

Part of the magic of studying Ancient Greece is that, given the limited sources, a week’s worth of reading on a narrow topic could allow you to ingest the breadth of relevant primary sources as well as a handful of contemporary scholars arguing about what it all means. As Kagan once put it, “that’s a very unusual situation, in that it has the great advantage that the teacher is not in the position of the all-knowing master who can tell you everything you need to know. [The student] can find it out just as well as [the teacher] can!” This fact lets students be at “a very high level of analysis, but not swamped by all the information they don’t have that the other guy has.”

Kagan’s courses left me with two central lessons. First, the conviction that studying political history isn’t just a game. People made decisions that altered the course of history, and understanding the dynamics of those decisions can speak directly to contemporary issues.

Secondly, if you aren’t interrogating sources and reading critically, you’re wasting your time. Even Thucydides, the ‘Father of History’, had his own agenda and sought to frame events to the ideas and people he cherished in the best possible light.

The current debate on China certainly takes itself seriously. But it lacks deep, systematic engagement with government sources. Particularly as opportunities on the ground for bottom-up interview-based research dry up, what we’re left with are speeches, propaganda newspapers, and government policy announcements.

That’s not the worst thing in the world! There’s far more in open source available about China, the CCP, and the Chinese government than there ever was about the USSR during the Cold War. While you don’t get the ‘blessing’ of a limited source pool for a college seminar, the reams of text give newcomers to the field acres of fresh material to harvest. But the problem is, no one gets trained in how the PRC system functions and how to decipher Chinese government documents.

Contemporary academia rewards regressions over deep qualitative readings of politics, think tankers are rarely hired for their fluency in the language of Chinese bureaucracy, and intelligence analysts often aren’t given the time and training to skill up.

There are maybe two dozen academics and analysts outside of the intelligence community who have developed this skillset and actively engage in English in the public debate. Having had conversations with a number of them over the past few weeks, nearly all were more or less self-taught.

I want to help create a cadre of a few hundred. What China watchers with language skills need now is the training and set of modern tools (think Genius.com or a CCP Sefaria) to do the sort of work the likes of Alice Miller, Geremie Barmé, Tsai Wen-Hsuan, Ryan Manuel, Dan Tobin, Holly Snape and Ling Li produce.

If you’re interested in joining this cadre, please fill out this form to help me get an understanding of where you’re coming from. And if you’re interested in supporting such an endeavor, either financially, institutionally, or through teaching, please reach out by responding to this email.

Newsletter Year in Review + Future Plans

My deepest writing this year touched on the chip industry. By focusing on the political economy questions and geopolitical tensions that increasingly drive developments in the sector, I’ve been able to bring a fresh perspective to some current debates.

Earlier this year, I published a three-part ‘Labs over Fabs’ series alongside Chris Miller and Danny Crichton exploring research funding, talent, and the role of open source in rebuilding the US chip ecosystem. I also authored a piece with Terry Daly about how Beijing could hit back on chips and wrote for Rhodium on how China’s chip industry is running faster but still falling behind.

Expect more in this vein—I’m currently working with the Day One Project and Hassan Khan (who wrote a fascinating PhD thesis on how research institutions failed to rise to the challenge of a post-Moore Law paradigm). We explore how the US should support the next generation of semiconductor research and will have a policy paper dropping in mid-January.

This year the newsletter also featured some strong Chinese translations, including on

My favorite one was of a 36Kr piece exploring China’s chip Theranos: HSMC

The story reads like a Hollywood script: An audacious and motley crew of scammers with high school educations (but rumored Party-backing) convinced a district government hungry for chip-making glory to invest billions of RMB into their factory.

A string of unbelievable victories followed. Chiang Shang-Yi, the venerable chip-making veteran who led TSMC’s R&D team, joined the company. Under Chiang’s guidance, HSMC acquired a coveted ASML lithography machine. Success seemed inevitable…until everything came crashing down.

I’ve also been proud to run some fantastic guest columns this year:

Chinese economists debating amongst themselves what industrial policy makes sense

And my personal favorite (from a college sophomore no less!): a profile of Chinese blogger Chairman Rabbit, China’s ‘Cosmopolitan Patriot’. I’d love to do more profiles of leading Chinese public intellectuals if anyone is up for writing them.

I’m always looking for interesting pitches and am happy to pay!

Since I started working full-time this year, I’ve personally been writing less in this newsletter. I hope for that to change in 2022, starting small with more brief takes on news items, books I read, and papers I come across (à la The Diff).

As a longer term goal, through the Emergent Ventures fellowship I’ve met a number of folks who’ve written books piece-by-piece on Substack. This reframing makes a book project seem less scary.

The idea I’m currently most excited about is exploring the evolution of PRC technology policy since Reform and Opening. I hope to approach the topic in a similar matter to Rush Doshi’s ‘The Long Game,’ which wove together close readings of policy pronouncements, leaked documents and memoirs to paint a picture of China’s grand strategic aims. Hopefully the Open Source CPP project provides the methodological toolset for such an undertaking!

Podcast in Review + Future Series

I’m about a month away from my 200th episode. To put that in perspective, that’s five 40-hour workweeks of content!

I tried to capture the Dao of ChinaTalk in an episode earlier this year:

Understanding China is like one of the most important things that is happening intellectually today. It is a really fraught thing that a lot of people are doing irresponsibly. It’s sad and upsetting watching analysis of the country be simplified, skewed and flattened in a dangerous way.

I don’t have the answers or even much of an agenda when it comes to US-China relations. I’m am pretty ecumenical on who I invite on the show and think I’m doing something right knowing I have dedicated listeners that range from ex-Trump appointees to hard left college kids. But the one message I want to convey in my interviews is that doing objective analysis is important and making sure that you are starting from the facts and building up as opposed to starting with an ideological conclusion and backfilling from there.

If there is a ChinaTalk worldview, is that you can never ‘Understand China’, but you can be on a path towards understanding China. The fact that I can promote voices that I think are doing that in a responsible and thoughtful way and put them in front of an audience they might not have otherwise is a real blessing and responsibility I take seriously.

Some of my favorite shows this year have been ‘buddy episodes’ where the two guests have mutual respect and some pre-established rapport. Lizzi Li and Mike Forsythe coming on to gossip about Red Roulette, Dan Rosen and Jude Blanchette reflecting on Xi’s regime, and my series of shows with Adam Tooze and Matt Klein all fit this mold. Going forward I’ll start asking future guests who they’d like to do shows with.

I also really enjoyed doing strings of five or so episodes on the same topic. I’ve gotten a lot of positive feedback on my series on industrial policy, the space industry, and the R&D ecosystem. I was able to interview two think tank presidents (CNAS’ Richard Fontaine and CSET’s Dewey Murdick) and hope more are up for coming on the podcast. Doing groups of shows, as opposed to one-offs, lets me ask progressively smarter questions about a topic, while hopefully taking the audience a learning journey with me.

Ideas for future series include SOE governance and performance, critical emerging technologies beyond AI and chips, open source CCP research, Vietnam as a foil for China, and China’s tv and movie industry. Thoughts?

Going forward, I’d like to be more deliberate in picking topics. For the past few years, I’ve found show ideas either by scrolling on twitter, browsing academic presses’ websites, or searching ‘China’ in recent books published on Amazon. That has been fun but leaves me a little constrained by the tyranny of the new.

I’d like to find a way to record shows discussing books and articles not published in the past few months. I’ll start asking past guests if they’d like to do book club-type episodes discussing some of their favorites. Would paying subscribers be interested in live zoom book clubs that we then turn into podcasts? If you have other ideas for formats, let me know.

In 2021, I only had one show with a guest based in mainland China, Aizhe of 故事FM. This is not for lack of trying. Most Chinese academics just don’t respond, and this year a handful who initially agreed to come on the show later backed out. Perhaps more public intellectual-types (say a 梁文道) or people in industries that don’t necessarily touch as directly on sensitive topics (musicians, curators?) might be more willing to accept interviews.

It would be great to host a few shows in Chinese. My language ability is just on the edge of being able to do this, and perhaps changing up the language of the show would make it more comfortable for mainland scholars and guests to sign up. I think I’d probably need a regular co-host with better speaking and listening ability than I have—if you think you might be that person, do reach out.

And on the topic of co-hosts more generally, I’ve quite liked having guests with me in the booth this past year. It breaks up the routine, lets me give a platform for young folks to engage with people they admire and hopefully inspires more of people out there to start shows for themselves. If you have someone you’d be really excited to interview, consider submitting the idea here.

Growth and Revenue

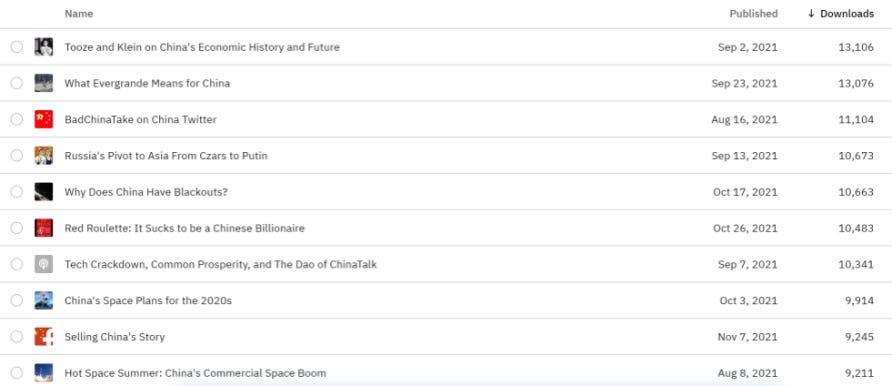

I switched podcast hosts so don’t have the data for the first half of the year, but here are the download numbers for the top 10 most popular episodes starting in August.

The best performing shows in the first half of the year include China’s Spies with Matt Brazil, Invisible China with Scott Roselle and US-China Ideological Competition with Dan Tobin.

Processing the fact that this many people listen to each episode is a real trip. Unfortunately, listenership for ChinaTalk has been largely flat through 2021.

Unlike tweets or YouTube videos, podcasts don’t really go viral. People don’t find new podcasts via scrolling on an algorithmic feed, they go out and actively search for new channels to subscribe to. This leads to a very stable listenership episode to episode, but strong shows don’t bring in many new listeners. Take for instance the fact that some servicable YouTube Evergrande content got 20x the downloads as my interview with Logan Wright.

I had a handful of conversations with YouTubers about their process and what makes a channel work, but it became clear that investing time to make shows that fit the YouTube mold doesn’t line up with the vision I have for ChinaTalk.

I want to produce content that approaches the highest level of thinking and analysis on China-related issues with energy and enthusiasm. Successful education-related YouTubers told me that they spend upwards of 2x the amount of time editing video as they do researching and writing. That said, if you’re reading this and would like to work with me on producing YouTube-specific content, please do get in touch!

Aside from reaching a smaller audience, the podcast ad market is far less developed than YouTube’s. A 100k viewed 10-minute YouTube video could net me $1,000. However, dynamic insertion at the beginning and end of each ChinaTalk episode currently brings in just $100 per show.

Further, at 10k downloads per show, ChinaTalk doesn’t hit the radar for the mass market podcast advertisers like SquareSpace or MeUndies. Even the more niche China-adjacent potential advertisers like language programs or specialty foods take too much time to pitch, onboard and chase around for payment to make it worth my while.

Thankfully, a number of you have chosen to support me directly via either Substack or Patreon. Your donations have allowed me to bring on a fantastic part-time editor Callan Quinn, pay contributors at least $100 per column, keep up a pace of five podcasts and 3-4 newsletters per month, and dream up bigger ambitions for this platform.

If you have the means, please consider supporting the show. $7/month will get you access to an ad-free podcast feed and $150/yr a first edition ChinaTalk mug, not to mention my boundless gratitude and buckets of good karma.

And please tell three friends about the show and newsletter. Actually, don’t just tell them, the next time you see them, take their phone, hit subscribe, and download the three shows you think they’d like the best.

If you’re looking for my favorites, check out this playlist I made on Spotify of my Top 10 shows. One week from now I expect to see 3x growth!

Jordan,

I find this to be an exceptional review.

I already have my hands full processing all the input that I'm already receiving and then attempting to serve all the individuals that I serve. China and its affairs are on the periphery of my activities, not directly involved with anything I do and yet extremely influential in a secondary way.

I'm going to just subscribe for now and see how this fits in. I like the model you are presenting here, I'd rather pay just a couple of insightful people and pay them well, than a whole lot of sources that are mostly trash...so if this works for me then I may offer you more later.