The Three-Body Problem 三体 tells the story of humanity’s multi-generational war against a race of omnipotent aliens fleeing their uninhabitable native world. The book series, written by Chinese author Liu Cixin 刘慈欣, has a diverse and devoted fanbase that includes Barack Obama and Mark Zuckerberg.

Netflix’s new adaptation of the series is a hit. It’s ranked in the top 10 most-watched TV shows in 93 countries, and is now the number 1 most-watched Netflix show in the US.

But the reception of the show in China has been … mixed. Today, ChinaTalk brings you the rundown on the debate based on translated reviews from China’s version of IMDb, Douban 豆瓣, which currently has the show sitting at a respectable 6.8.

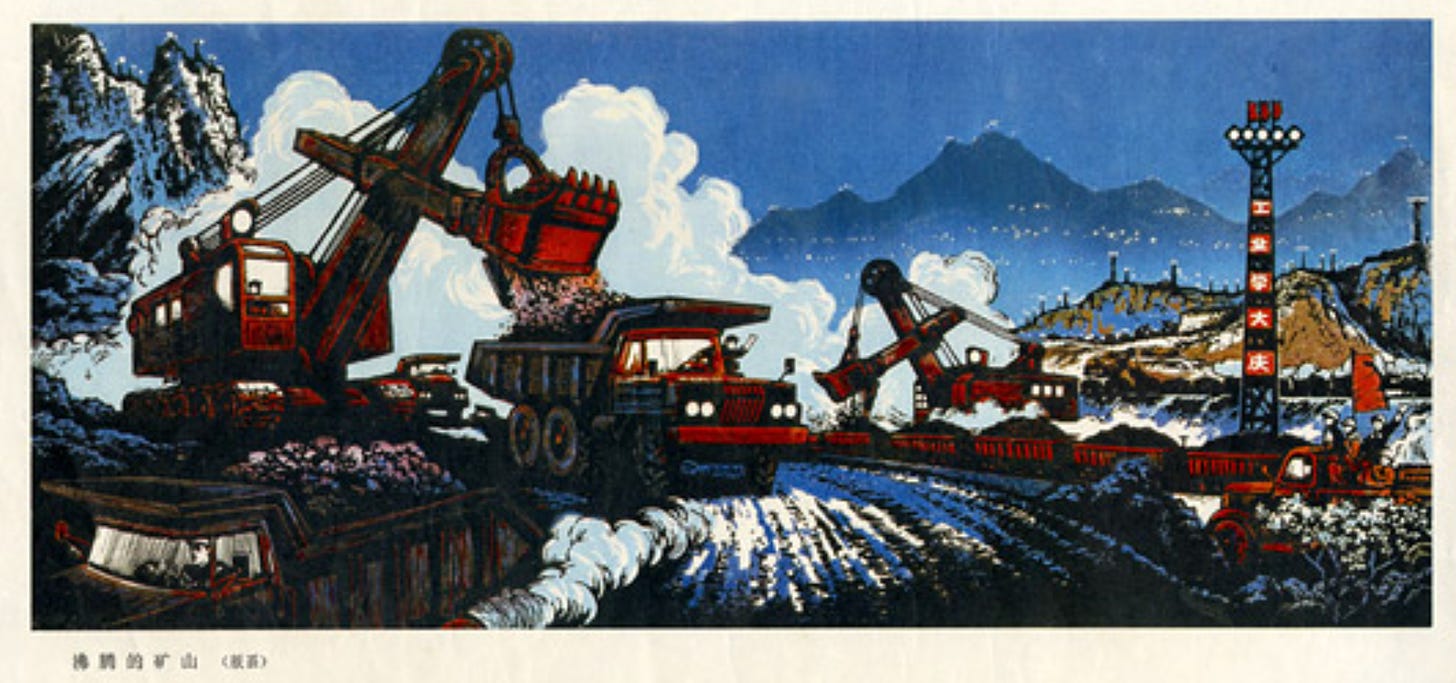

The Cultural Revolution

The Netflix adaptation opens with a scene from the Cultural Revolution: protagonist Ye Wenjie 叶文洁 witnesses a “struggle session” in which Red Guard revolutionaries beat her father to death for the crime of teaching bourgeois physics.

This scene has largely been taken off the Chinese internet. Similarly, Tencent’s adaptation only reveals the fate of the protagonist’s father, Ye Zhetai 叶哲泰, in episode 6. Instead of showing the struggle session, the facts of his murder are revealed clinically in a conversation between two other characters. There is no flashback.

But the Netflix version of the scene is exactly the way that Liu Cixin intended the series to begin. According to English translator Ken Liu,

When it was first published, the Cultural Revolution chapters were moved to the middle of the book because it was around the time of the 30th anniversary of the end of the Cultural Revolution, and such topics were deemed sensitive (but the chapters weren’t deleted).

When working on the English translation, Ken Liu recommended putting the Cultural Revolution scene at the beginning. Liu Cixin instantly agreed because that was the original intended order. Keep this context in mind when you see comments debating about Netflix’s “changes.”

A 5-star review posting from Germany speaks in code about the Cultural Revolution:

If my family beats children, outsiders shouldn’t comment … NOT. Did Liu Cixin protest this change? No.

A 4-star review with 4,000+ upvotes writes from Guangdong 广东:

Compared to the domestically produced filler-bloated drama, this adaptation is much more efficient in storytelling. Watching a series is different from reading a novel; the emotions conveyed through visuals are more immediate.

The key to understanding The Three-Body Problem lies in understanding Ye Wenjie. Understanding Ye Wenjie is truly understanding human nature. If you downplay the crucial factor that led to her transformation, the entire story loses its meaning. Therefore, Netflix’s decision to place that segment of the story at the beginning is very appropriate.

A 1-star review from Yunnan 云南 with 4,000+ upvotes:

On one hand, they’re lavishing attention on our Cultural Revolution, but on the other, they don’t even dare to write the slogans about overthrowing American imperialism.

A 3-star review from Anhui 安徽 added:

The expectations were too high, and it really doesn’t compare to Tencent. … What’s even more interesting is that Netflix did manage to film the part of the story that China dares not touch. Upon comparison, however, I still feel Tencent’s version is better. Tencent, although compromising and cutting corners, did a better job of delicately portraying the complexity of Ye Wenjie’s inner feelings. Compared to Netflix’s portrayal, where Ye Wenjie only displays anger on her face, Tencent’s portrayal hides the complex emotions beneath the surface. In terms of depicting this unfathomable aspect of human nature, Tencent comes out on top.

A 2-star review from Heilongjiang 黑龙江 writes:

I was actually thinking, if they changed Wang Miao 汪淼 to a British person and made Luo Ji 罗辑 black, then why not portray Ye Wenjie as a black woman? Her father could have been assassinated by the US government during the McCarthy era for spreading communist propaganda. This storyline would have been perfect for their adaptation. It would have been coherent, with only the Cultural Revolution part being faithful to the original, while everything else is changed. Keeping everything else intact but only partly sticking to the original makes it really uninteresting.

Wang Miao was not changed to a British person (more on that in the next section). Regardless of whether this person actually watched the show, this review has 5,000+ positive engagements. If we’re racebending all the characters, why keep the Cultural Revolution as a plot point?

Liu Cixin answered this question in a 2019 interview with The New York Times: “The Cultural Revolution appears because it’s essential to the plot. … The protagonist needs to have total despair in humanity.”

Note that this is also personal for Liu Cixin, who grew up during the Cultural Revolution. From the same NYT article:

The Cultural Revolution had torn Liu Cixin’s family apart. He was just 3 when the political upheaval began, and still remembers hearing gunshots at night and seeing trucks full of men wearing red armbands patrolling the city where he lived in Shanxi province. When the situation there became too volatile, his parents, who worked in a coal mine, sent him away to live with relatives in Henan.

Cultural export or cultural appropriation?

The most prominent debate was about race/gender swapping in the Netflix adaptation. Here are the swaps, for reference:

Jovan Adepo (black American) plays Saul Durand, based on the character of Luo Ji;

Eiza González (Latina) plays Augustina “Auggie” Salazar, based on the character of Wang Miao;

Alex Sharp (white British guy) as Will Downing, based on the character of Yun Tianming 云天明.

Note that the phrase “Cultural Appropriation” 文化挪用 does not actually appear in these reviews. I’ll let the comments speak for themselves:

A 3-star reviewer posting from the UK writes,

There’s a black guy, there’s an Asian, and the female Wang Miao is Mexican. It seems like everyone is satisfied, but I’m not. … Pros: The story has a somewhat tight, movie-like quality, the Cultural Revolution storyline is decent, special effects are decent. Cons: The actors are wooden, especially Ye Wenjie, heavy on political correctness (the Fab Five: Asian, Mexican, black), dialogue is subpar, plot adaptations are unreasonable (everyone on Earth can see the flickering).

The same 3-star reviewer from Anhui continues their comment from the last section,

The well-regarded contemporary Chinese male characters of the original work were assigned to actors of other ethnicities, while the not-so-great character, Da Shi 大史, remains Chinese. … Ye Wenjie’s simple and kind husband, Yang Weining 杨卫宁, was changed to a sly and sleazy colleague involved in plagiarism, and Ye Wenjie’s daughter turns out to be born of a relationship with Evans. Various overt and covert signs make it hard not to feel uncomfortable. Does this predominantly white-led production team have elements of racial discrimination? Have Chinese people truly gained a foothold in Hollywood? From The Joy Luck Club in the last century, to Mulan, Shang-Chi, and now The Three-Body Problem, it seems like all Chinese narratives in Hollywood only serve to amplify stereotypes.

This is basically the least charitable way to read all of these plot modifications. This person is also not comparing the Netflix version with the book, but rather with Tencent’s adaptation. How do I know that?

First, Yang Weining is only a “simple and kind husband” in the Tencent adaptation. In the book, Ye Wenjie kills her husband to conceal her communications with the Trisolarans. He doesn’t contribute much to the plot because he is killed so early on.

My impression was that Netflix cut that part of Ye Wenjie’s backstory, which made Yang Weining no longer useful as a plot device. Evans was then slotted in to allow more romance-drama within the ETO. It’s a weird choice to be mad about interracial relationships in 2024 — but let’s move on.

Second, I don’t anyone who read the book would say that Da Shi is a “not-so-great character.” Here are some helpful quotes from the book to contextualize Da Shi:

Buddy, you’re the one who was right!” Da Shi laughed, shaking his head. “I would never have thought that actual fucking aliens would be involved!

To be honest, even if I were to look at the stars in the sky, I wouldn’t be thinking about your philosophical questions. I have too much to worry about! I gotta pay the mortgage. … I’m a simple man without a lot of complicated twists and turns. Look down my throat and you can see out my ass.

The Trisolarans who deemed the humans bugs seemed to have forgotten one fact: The bugs have never been truly defeated.

The fair criticism of the Netflix adaptation is that it underutilizes Da Shi and doesn’t give him the lines he deserves. But to imply that he was cast as Chinese because he’s a “bad character” says a lot more about the psychology of the reviewer.

It’s also pretty weird to say that adding black and Mexican characters to the cast advances white supremacy. As Da Shi would say, “Anything sufficiently weird must be fishy. … There’s always someone behind things that don’t seem to have an explanation.”

Some highly rated reviews also defend Netflix’s casting choices:

A 4-star review from Zhejiang 浙江:

The original author of The Three-Body Problem encourages adaptations of the work. … The Netflix adaptation has been broadcast in over 190 countries and regions worldwide. This is an opportunity for global exposure. Why do some people always criticize? Is it a bad thing that Netflix’s version is popular worldwide?

Another 4-star review from Zhejiang:

Is it really so difficult to admit that it’s better than the mainland version? Why must we nitpick over irrelevant changes like gender and skin color? With an all-Chinese cast, do you really think it was made for Chinese viewers? It’s not even available online in China.

Wait, Liu Cixin approved all the casting changes? Why did he do that? In his words, “Science fiction is a literature that belongs to all humankind.”

Here’s a longer endorsement from the post-script of the first book in the series:

On Earth, humankind can step onto another continent, and without a thought, destroy the kindred civilizations found there through warfare and disease. But when they gaze up at the stars, they turn sentimental and believe that if extraterrestrial intelligences exist, they must be civilizations bound by universal, noble, moral constraints. …

I think it should be precisely the opposite: Let’s turn the kindness we show toward the stars to members of the human race on Earth and build up the trust and understanding between different peoples and civilizations that make up humanity. But for the universe outside the solar system, we should be ever vigilant, and be ready to attribute the worst of intentions to any Others that might exist in space. For a fragile civilization like ours, this is without a doubt the most responsible path.

Cultural exports are not a zero-sum game, and different adaptations can all be worth watching. The urge to pit China’s domestically produced adaptation against the Netflix series seems a distinctly nationalist impulse.

But blaming the Jews is apparently easier than egalitarianism. One star from Zhejiang:

The protagonist group has been changed to the “Oxford Five” 牛津五人组, with no relation to China, and only the Cultural Revolution segment of Ye Wenjie is left, tsk tsk tsk. The ETO symbol of the Hexagram has also been changed (the director is Jewish). F*cking Netflix’s show has nothing to do with our “Three Body.” It’s okay to make changes, but the problem is, does the core theme after the changes still have any relation to the original work? Without understanding modern Chinese history, it’s impossible to capture the essence of The Three-Body Problem.

Speaking of core changes…

Good-Faith Criticisms

The previous section was about criticisms based on nationalist culture-war talking points. This section will discuss criticisms of Netflix’s fidelity to the spirit of the book.

Many reviewers were disappointed that Netflix simplified the book’s scientific explanations for international audiences. Other topics of debate include Ye Wenjie’s sex scene, the quality of the dialogue, and the fast-moving pace of the Netflix show.

“To effectively contain a civilization’s development and disarm it across such a long span of time, there is only one way: kill its science.”

— The Trisolarans

1 star from Beijing:

Book fans’ nightmare! Do foreigners not understand high-level ideals and macro spiritual pursuits, with their minds only focused on lowbrow and vulgar matters? Just like when “Death Note” was remade, the first thing they do after obtaining the notebook is to go flaunt it to girls. It’s ridiculous. This version can be considered a spiritual contamination nuclear bomb. If the Trisolarans saw it, they would probably flee the galaxy.

3 stars from Guangdong:

If viewed as an ordinary science fiction work, it’s still acceptable, but as an adaptation of The Three-Body Problem, it’s really hard to describe. It’s understandable that the production team made bold changes for a global audience, but many of the adaptation choices are disappointing. For example, condensing the main characters from all three books into the first installment, and making them close friends, resulting in just a dozen or so people constantly dealing with the life-and-death matters concerning humanity, making the overall scale seem small.

Additionally, adding several kissing and sex scenes for Ye Wenjie diminishes the sense of power attributed to her leadership, essentially altering her character. Furthermore, the overall pacing is too fast, compressing the motivations and backgrounds of many characters into tiny fragments, and the depth and complexity of the characters are not sufficiently explored. Many actions that require scientific explanations are glossed over, aiming to provide viewers with a pleasurable, fast, and easily understandable viewing experience, which is quite lazy.

5 stars and 1,000 upvotes from Guangdong:

The screenwriters are obviously top-notch, transforming the Chinese background of The Three-Body Problem into an international version while still retaining the basic development of the original work. The costume and set design are also first-rate, and it’s impressive that the Netflix team could essentially recreate scenes from China’s Cultural Revolution–era struggle sessions. Respect. Thank you, Netflix, for not abusing this IP. Looking forward to even better performances in the upcoming seasons.

A 4-star reviewer from Jiangsu 江苏:

Tencent is like an elementary school student copying homework, mindlessly copying everything regardless of its appropriateness, without changing a single word. Netflix is like a college student bullshitting an essay, making changes here and there, piecing things together, which still seems somewhat reasonable.

A 3-star review from Hebei 河北:

It’s not reasonable to expect Netflix’s adaptation to fully respect the original work. Since Netflix doesn’t have a market in China, they won’t produce a series with a Chinese protagonist. Isn’t it said that the disasters, setbacks, and dangers faced by characters in science fiction literature are challenges shared by all humanity, rather than just one particular ethnicity? Can’t the same story be told from the perspective of other human beings facing the crisis of the Trisolaran invasion?

After binge-watching all 8 episodes, Netflix’s adaptation retains the events from the three books but redesigns the characters using the storytelling techniques typical of contemporary American TV. Each character represents a market where Netflix operates. This character rewrite intensifies emotional entanglement but also narrows the original scope of the story, almost turning it into a teenage drama series, which is quite annoying. This Americanization of the adaptation makes each episode’s story more complete, paces faster, and production quality is fine. It’s entertaining and watchable.

4 stars from Beijing:

I binge-watched it all in one go. The storytelling pace across 8 episodes is smooth, with just a few individual plot points seeming a bit unreasonable. Overall, the adaptation is superior to Tencent’s approach, which seems to only aim at pleasing the masses. The mission of global streaming platforms is to allow the widest audience to quickly immerse themselves in the story. Those interested in the IP will naturally seek out the original work to read. Isn’t this an excellent way to expand the influence of the story? Are your standards for judging movies and TV shows so low that if it’s not a shot-for-shot remake of the original, it’s considered a travesty? The true meaning of adaptation lies in daring to make bold changes to the structure and characters, engaging in reinterpretation. Otherwise, if AI can simply convert text into video, what else is there left to film?

If you’ve seen the show, which of these criticisms do you find salient? Let us know in the comments!

I watched both series back to back. The Chinese version was I believe, deeper and more profound. More philosophical. And closer to the books. (Disclaimer I only read the first two). The actors were exceptional imho.

The American version irritated me (an American grandmother) because the changes in gender and race were unnecessary, and gratiuitous. It was also more entertaining than the Chinese version because Americans are good at pure entertainment.

The storyline was easier to follow in the netflix take.

Honestly, im so happy that we have two versions. They complemented my understanding.

Great books! And two solid series.

I just wish netflix hadn’t taken such broad liberties with the original.

Chinese soft power…