Adam Tooze and Matt Klein Return!

Was Stalin a Hamilton Fan? Can Bolshevism Break The Link Between Capitalism And War? Does Elite Conflict Drive Policies Towards International Institutions?

This past week on ChinaTalk, I hosted Adam Tooze (now on Substack!) and Matt Klein, author of Trade Wars Are Class Wars. They picked up right where they left off last September. We discussed whether Ricardo’s theories of comparative advantage actually work in a globalized age, why Stalin’s embrace of “socialism in one country” was a response to the hegemonic power of British (and American) capital, whether a Bolshevik Revolution is the best way to solve global inequality, how intra-elite conflict drives sovereignty-limiting engagement in international organizations, vaccines, and a whole lot more. What follows is an abridged transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

Was Stalin a Hamilton Fan?

Jordan: Hamilton and the German model versus Adam Smith and David Ricardo. What do the latter two get wrong and Hamilton get right?

Matt: Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage is well known and often taught, but I don't think a lot of people read the original text. I had not until I started doing research on this book. One of the things that's interesting is that Ricardo makes a lot of specific caveats and assumptions about the circumstances under which his argument makes sense. That argument is that for certain societies, you want to specialize in one particular activity at the expense of all others.

Ricardo makes the point that this only works because businesses can't easily pick up and move and you can't easily move workers from one society to another.

They talk about Portugal and England, textiles versus wine, which you can think of as a high-tech industry of the time versus a low-tech but valuable agricultural product. As he says, if it were the case that the investors in England could do it, then obviously they'd want to just make the textiles in Portugal as well. They'd move the workers and the machines. Thankfully they can't do that, or they won't do that, because they're afraid of foreign investing. It's too dangerous and difficult.

Hamilton's point was “Actually, we probably can get them to do that. If you make it attractive enough.” He was writing in the 1780s, 1790s, when the U.S. was predominantly an agricultural society. It was not a manufacturing society. It was very dependent on imports from Europe. In fact, that was a deliberate policy of the British empire and one of the reasons the colonists were upset with the policies of the British crown.

Hamilton’s point was that it’s not inevitable. There were specific contingent circumstances that made that the case, but we can change those things. His point was that we can get Europeans to help us industrialize and modernize if we present them the opportunity of a really big profitable market that they have to be able to put money in and, if they do that they can make money. More importantly, we'll develop all the various skills and technologies and abilities that we didn't have before and make the economy more diversified.

That was something that Ricardo didn't really discuss in his model. Ricardo's model would probably would have said it was a bad thing because, from the perspective of England, if you move all your production to Portugal that's great for Portugal, but it's bad for England.

I think that’s an important distinction.

You mentioned the German model. Friedrich List was a German political dissident, or early nationalist, who ended up being kicked out of the German state. He comes to the United States and sees the U.S. as a model for what German unification should look like, starting with economic unions were a big free trade block and a big domestic market, and then leading to a strong political union. He has a line basically saying, “if you want to understand political economy and just look at the United States.”

More controversially, you can look at what happened in the Soviet Union under Stalin. I don't know to what extent they were thinking of Hamilton, per se, but a lot of the arguments and logic fit in with how they were thinking about this stuff. To the theme of this podcast, I think you can look at Chinese experience in the past several decades as being in a very similar view of: “We're a poor country that's not as technologically sophisticated, but if we create the conditions that foreign businesses from societies that have the technology we want to invest here and develop them, then they'll make money and we'll make money and be better off in the long-term.”

So I think that you should consider this long trend. The traditional Ricardian view doesn't really account for any of these circumstances.

Adam: I love the suggestion of a link between Stalin and Hamilton. I actually Googled this and I don't think there is one, as best as I know. I’m sure if anyone had come across some stray references to Hamilton in the writings of Stalin, that would be a nugget familiar to all of us. The line does run a little bit closer through List, though, because the German socialists of the late 19th century did spend quite a lot of time thinking about the possibilities of national economy. Of course, the crucial slogan for Stalin which was at the time totally heretical is "socialism in one country.”

The Marxist movement broke apart over this idea because one of the fundamental legacies of mid 19th-century Marxism was anti-nationalism. It took liberal nationalism to be camp, to be nonsense and the idea that capitalism operated in national boxes struck Marxists as the thing that needed criticizing. Flaming denunciations of the new discipline in Germany, particularly of the universities of national economics. But they haven’t yet seen the Soviet Union and don't know what it would actually be to make a revolutionary state in the setting of international diplomacy, balance of power, and global politics, that we see in the twenties and thirties.

And it's out of that, I think, that Stalin's vision is born plus the war economies.

But perversely and ironically the great shock for the Communists of the twenties is that their icon, imperial Germany, which is serving as your European stand-in for the Hamiltonian project, was defeated by a globally articulated British-style capitalism.

That’s when Stalin says we must industrialize or be crushed. He's not thinking at that moment of Nazi Germany, which has not yet emerged. He’s actually thinking of the oppressive power of a globe-spanning British capitalism which, with its ability to drag the Americans in, had proved completely overwhelming in World War One

Matt: I like the theme of encirclement, which is one of the big motivators. Some minutes of the Central Committee, or what have you, show Stalin explicitly saying the reason why you have to have a degree of industrialization and economic self-sufficiency is to protect yourself from the fact that everyone in the rest of the world is trying to potentially overturn your revolutionary state.

Adam: The British in particular though, let's be clear, Stalin isn't impersonal, and to that extent, there's another structural analogy to Hamilton, right? What we're basically talking about is, how do insurgent projects of national autonomy assert themselves against global frames set by other powers?

Historically the British were the power to do that. They're the first people to create something like an ironclad global hegemony. So all projects after that have to be pitched against that real existing project in the same way that America becomes the target for that kind of national economic development project after 1945, because globalization has a name, there's a power attached to it. It doesn't just exist, only liberal ideologues think it's flat. Everyone with a brain understands that it's hierarchical.

One of Trotsky's profound disillusionments with Stalin is that Stalin thinks the British empire is the main enemy, whereas Trotsky is quite clear about the fact that behind the British stand the Americans. It is the transatlantic North Atlantic nexus where power really resides: somewhere between the city of London and JP Morgan, broadly speaking.

Can Bolshevism Break The Link Between Capitalism And War?

Jordan: So we've done Stalin. We've done Trotsky. We can't leave Lenin out of the picture. Matt, what does Lenin get right and wrong about the way capital moves around the world?

Matt: The context here is we're talking about Lenin’s theory of imperialism, which is heavily influenced by John Hobson, who was a British economist and social critic writing about 15 years earlier. If you take Hobson’s critique of imperialism, which was focused on the Western European colonial projects in Africa, China, India, and so forth, and apply that to the modern world, I think you can draw a very clear line.

Lenin took that and then extended it to explain World War One, and then what he believed was the inevitability of the triumph of global communism. Obviously, it's not what happened.

I don't think there's great evidence that World War One was caused primarily by competition among the imperialist powers for colonies and the economic advantages associated with it. I think it's fair to say that mercantile competition probably didn't help maintain relations between say, Germany and Britain, but I don't think that was the main cause.

More broadly, I don't think that World War One and imperialism more generally, even if you think those things are connected, are inevitable consequences of a capitalist system more broadly. Even though this sort of pattern has recurred in different forms over time, how is that inherently connected to a market-based economic system? It's not very clear to me. It's something that was fixed before, in various ways, without having to overturn market-based society. You don't need to have a complete Bolshevik Revolution to fix the issue. The idea that it represents an inherent failure of capitalism doesn’t make a lot of sense. I think probably the biggest disagreement we would have with Lenin is that you can have the view that inequality in one's society leads to imbalances between them without saying that the solution is massive global revolution.

"International Red Day — The day to mobilize the proletariat of the world against the armies of imperialism" [Source: Brown University, Views and Re-Views: Soviet Political Posters and Cartoons]

Adam: The thing I want to save Lenin from is the accusation of inevitability. I think that Lenin's theory is more that contrary to the rather liberal kind of glossy optimism of mid-19th century Marxism. We have to remember the Communist Manifesto is written in 1848. By the early 1900s, it's 50 years old.

What Lennon is saying is, “A new, really terrifying, possibility has opened up. Marx told us we would move smoothly through feudalism, bourgeoisie and then there'd be a revolution and we'd end up in socialism, and ultimately communism. But what if something worse happens? What if you get global competition, the frontiers close, and the globe becomes a terrain in which capital argues? What if capital manages to hijack the power of militarized nation states and then we slide over the cliff.?”

He doesn't really provide a detailed account of the 1914 crisis. He doesn't need to. All he needs to say is we have the possibility of sliding over the cliff into something truly apocalyptic. What's really striking about the Bolsheviks in 1915, 16, 17 is they become more and more apocalyptic. Bukharin is the same, basically saying, “What if the possibility of a total annihilating war (a bit like nuclear war in the Cold War era) erases any possibility of positive progress?”

What then are the options for revolutionaries? You can't take the Menshevik line of waiting for it to turn out for the best because capitalism isn't heading you that way. Potentially, capitalism opens up the possibility for the socialization of much more sophisticated means of production, but it's now revealed to us the possibility that it could end up with the Kitcheners, and the Luddendorffs in control and they will literally annihilate humanity with the means that are available to them in ever larger wars.

Ludendorff was planning World War Three, Four, and Five in the later stages of World War One. So Lenin isn't entirely off base, and that's what warrants something which 19th century Marxism had not licensed, which is volunteerist leaps. To go back to the utopian revolutionary tradition of the mid-19th century, which is essentially a coup.

The much bigger point that you raised is, “What is a plausible account of the relationship between capitalism and big war?”

Lots of ink was spilled, especially by British historians in the fifties and sixties, trying to demonstrate that the war didn't start the way Lenin predicted. I think lots of it is totally beside the point.

Think of it this way instead: in terms of uneven and combined development, the analytic that Trotsky offered. Does global capitalism develop evenly? No, if it doesn't develop evenly, it shifts the balance of power. If the balance of power shifts, like Gilpin and other people argue, you have mounting tensions and all you then need is any casus belli. Somebody is going to see a strategic window of opportunity and jump through it.

This is exactly what we see before 1914. The swing variable is Russia because no one knows which way it's going to go. It could be a basket case and head down 1905 defeat at the hands of the Japanese; towards the civil war scenario of the 1920s where everyone pitches in to tear it apart like people were prophesying for China 20 years earlier. Or it could harden; develop into a power state and (if the French pump enough capital into it to build those railways) it will be the all-decisive military factor it becomes by 1945.

Germany had to align its strategy with regard to those two options. Japan did as well. On either end of the Russian Empire, you saw those two powers asking, “Do we jump now? Or do we get squashed later?”

But driving that is an uneven logic of economic development combined with lending. So to my mind, the bit that's explosive is not southwest Africa or Tanzania, or even the Suez canal, those kinds of struggles aren't large enough.

From the point of view of German military panels, we know flat out that the fundamental question they're benchmarking their planning against is how rapidly Russia's railway network develops. The link is one-to-one. You can see Ludendorff literally saying, “If they build that railway and I need to bring my military planning forward, I need two weeks less in my mobilization plan so as to be able to do the Schlieffen plan.” The military-industrial, military-economic entanglement is that direct.

I would agree with you that what Lenin did was the bolt a heavier form of inevitability on to that but it isn’t an inevitable claim that revolution will reside. It's a huge challenge for revolutionaries to face: what are profound tensions that are indeed inevitably going to arise?

That surely is what we've seen in the last year in the United States. A clear instance of that logic is being played out. Explicitly in the heads of American planners, they know that they're in that situation and formulate their problem in these terms: “China's overtaking. We have a window of opportunity. There are things we may be able to do in the meantime.”

I agree there are tactics we have for containing that. We have learned some lessons, but we may also misapply lessons. In particular the idea that this is like the first Cold War and we can win it the way we won the Cold War. That may surely be a misapplied lesson of history in this case.

Matt: It’s interesting that it wasn't inevitable that Russia would industrialize and that it would industrialize in a way that threatened Germany in that timeframe.

Does Elite Conflict Drive Decisions To Join International Institutions?

Jordan: In your book, Matt, there is a throwaway line about how post-World War One suspicion of international organizations in America echoes the way China looks at the rest of the world today. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Matt: In the 1920s, America was the decisive factor in ending the war and became the predominant economic power. There were efforts to reform the international system. The league of nations was being created. But at the same time, there was a concern among certain elements within the U.S. that because the Europeans were going to be predominant in governing them, the purpose of those institutions was essentially to hold down the major power, which was the United States. That was why there was a big reversal within the Senate and Congress before Wilson left office.

In fact, one of the reasons why Wilson, and then afterwards the American government, was so insistent on getting debts repaid, including from their allies, was precisely to limit their power and stop them from re-militarizing: really the belief that you can't trust the Europeans. I think it's consistent with the idea that you don't want to be in an international institution where you get out voted by Europeans, which is what the League of Nations arguably would have been.

Talking about China, there's some important differences there. It's not as if we just had a major world war where China emerged triumphant.

China has become much more economically and militarily powerful than it was 30 or 40 years ago, but it’s power within certain international institutions has not grown commensurately. Even if it did grow commensurately, the combination of the U.S., Europe, Japan, and so forth would still outweigh China in any sort of international institution. You can understand why they would be reticent to submit. If you are the single biggest power and you think you can get subsumed by an international organization, then you're going to be hesitant to give that organization too much authority over your own internal affairs, especially if you think that the plurality might be hostile to you.

Adam: We could add as another wrinkle that another reason why a particular group of elites in a particular country might subscribe to various types of sovereignty limiting strategy is that they don't trust other elites in the same country. So it's not so much a realist nation-on-nation type logic, as a struggle for power within nations.

I think we saw that operating very aggressively in the 1920s within Germany, Japan, and Italy. Inside each one of those countries, an inter-elite struggle was going on over the orientation of strategy: whether towards a profitable conformity with an American- and British-led world or a gamble on national aggression.

I think some people rationalize Beijing's moves, which are often quite perplexing, in similar terms. In other words, there are elites within China that are more orientated towards a sort of almost Italian strategy, using external constraints to achieve various types of power shift within your own country: the Draghi strategy.

America, presumably, would be building a global order that would contain the rising power of China. America didn't go very far towards that move [under Trump], but a rational strategist in China might anticipate that America would be building liberal international institutions systematically biased against the emergence of Chinese power.

The crucial thing is to differentiate. So I think we see China playing a rather skilled game in the UN, which is an unweighted global body where they can assemble coalitions which are quite powerful. BRI is part of that.

That was why the UN was increasingly uncomfortable for America from the 1960s onwards. As soon as you start multiplying post-colonial States, many of them are actually aggressively anti-American in their positioning, whereas the IMF and institutions like that are shareholder weighted.

It's very difficult for an up and coming power like China to make much headway in the IMF, because they have to overcome an incumbent American veto that just can't be moved. Whereas in the U.N., the Americans are so sleepy and ideological that they don't even appear to play the committee game with real energy. In the IMF they certainly do. So there's a huge difference there in different types of international organization.

Matt: Yeah, I think that's a great point about the use of external constraints to inform, domestic politics, which of course fits in, with one of the themes of the book that thinking about countries as these discrete units of analysis is not helpful.

With China, I get the impression that joining the WTO and for that matter, a lot of the stuff that was done in terms of the liberalization of financial markets in the context of IMF rules is very much driven by internal conflicts and debates among people with different views on what would be best for China.

We don't really have a great insight into what those debates looked like and how the decisions were made, but I think it's absolutely right to say that the extent China is involved in a lot of international organizations reflects competing interests within China competing views about how the country should engage with the rest of the world, and what's good for the people who live there.

Adam: What's really shocking, I think, is that exactly that debate is going on in Washington right now on the turn in American strategy towards China. One of the fundamental issues is: do we treat it as a block? If we do treat it as a block, how aggressive do we think it is? Or do we actually think the Chinese elite is split? Do you, as that anonymously authored paper insisted, treat Xi Jinping as a separate factor?

What I find disappointing about the current American debate is that it seems so impoverished in terms of its analytic. It's basically “Bad King Xi” against a more processually-orientated, bureaucratic party. It's very personalized. It's very ideological. Whereas I think, as Matt was saying earlier in the conversation, an analytic organized around socioeconomic interest groups and strategies of economic development for China would probably be more fruitful.

I think the conversation going on amongst Western China Watchers over climate is much more interesting because there we actually are having a political economy conversation about whether Xi's leadership group and the folks who are pushing the decarbonization agenda can prevail over the big utilities and entrenched coal interests.

That's where the conversation gets real. When it's a bunch of American liberals trying to figure out how bad they think King Xi is, I think that's an impoverished conversation.

It's also a dangerous conversation because as a historian of the Third Reich. I cannot help thinking of appeasement. The 1930 strategy with regard to Nazi Germany was explicitly modeled on the idea that you could separate Göring from Hitler; that Göring represented the serious, sensible Germans, and a little bit of business talk with Göring would get you where you need to go.

So you actually have to have the right model of the regime first. If you have a bad model and then you apply this clever side-picking strategy, it can massively backfire.

Matt: This is also a characteristic of some of the debates in the U.S. about the Soviet Union: “They're the liberals. We want to reinforce it.” It turns out, you don't know who those people really are, or maybe there's much less of an internal debate than you thought.

Adam: And why would you trust the liberals more? How well has democratization gone in Egypt from the point of view of American strategy? I think the same analogy applies in spades to China. Normatively, we might prefer that for all sorts of extremely good reasons, obviously starting with human rights and the rule of law. But from the point of view of grand strategic consideration, the idea that democratization is some sort of recipe for easier geopolitics for Western States seems like a gamble with incredibly long odds.

Will “The Jab” Usher In A New Era Of Chinese Public Diplomacy?

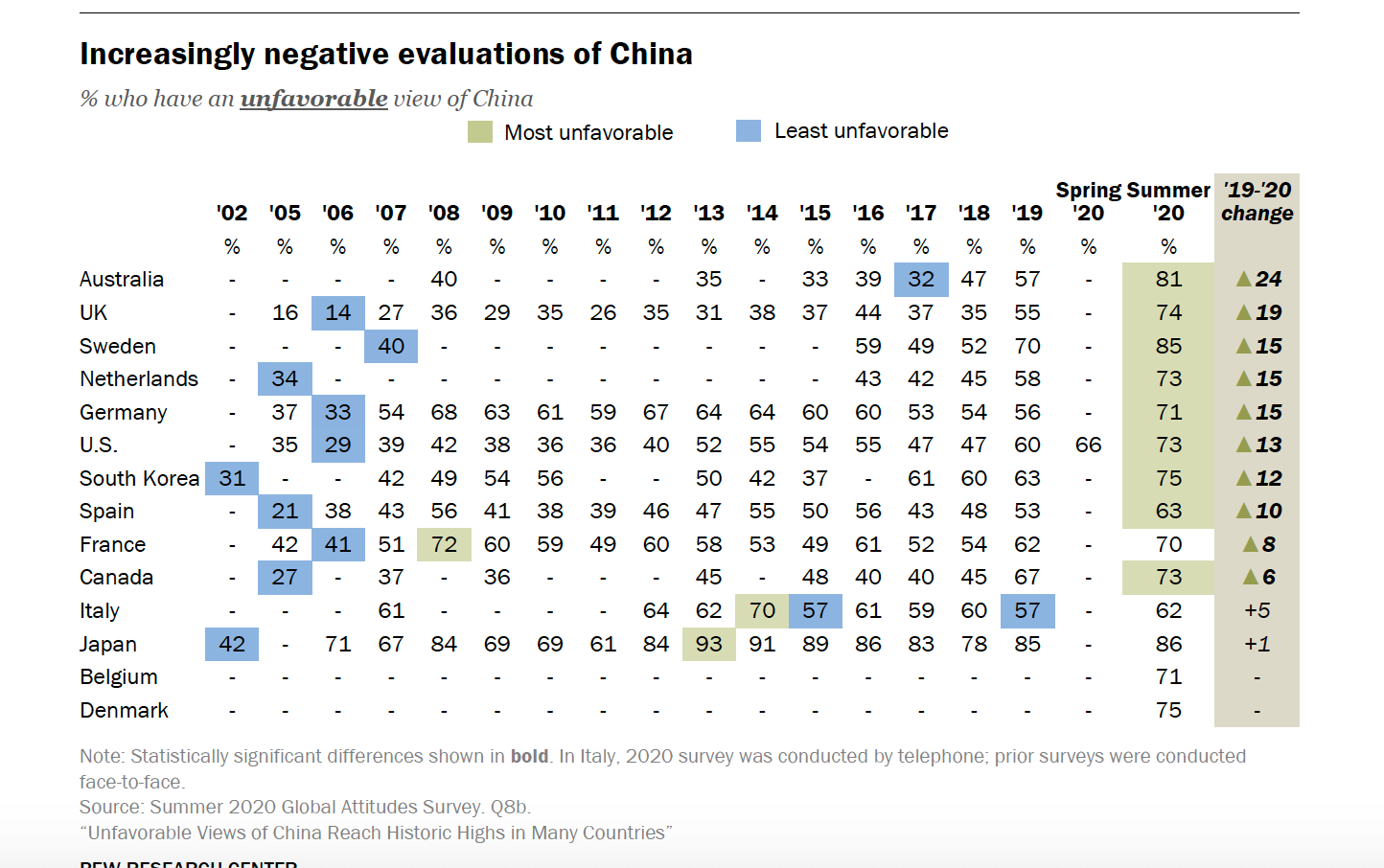

Jordan: Let’s step back and think about the way that the Chinese government is thinking about elites, as well as the elites in comparison to the broader society. What I've found remarkable is even though you've seen China’s poll numbers drop spectacularly over the course of 2020 [Pew also found that89% of Americans consider China an enemy or competitor], but you still see 50 Muslim-majority nations at the UN voting to approve of what's happening in Xinjiang.

At some point this tips, right? It clearly tipped in the United States. Playing the elite game and talking to Stephen Schwarzman and Ray Dalio about how cooperation is really important was able to run a very long road. But we've clearly reached the end of that, at least at a certain level. Following the extent to which elites will start to align more with their populations on China, outside the U.S., is a fascinating thing to watch. Whether the Chinese government can understand and process that and adjust will definitely be one to follow in the next few years.

[Source: Pew Research Center]

Adam: Which is why vaccines are so utterly fascinating, right? That's literally putting your faith in China in your arm, you are literally putting your body into the geopolitical arena and saying, “You know what, I may not like them very much, but…”

Chile has achieved a remarkable vaccination rate in part by being part of the original Chinese phase III trials. Their scientists were all over the vaccine and they know it pretty well. They trust it. Now they’ve got an exemplary vaccination rate by any standards, let alone a middle income country.

Given the botched geopolitics of vaccines in the West, that is going to be an increasingly prevalent issue. I'm not saying that there isn't overlap because we also have plenty of evidence of resistance to both Russian and Chinese vaccines on exactly the grounds that you're citing. But in the end if the West fails as badly as it does on the ground on issues like that, we hand the game to the Chinese. It's not just their cheap smartphones that we love. Large parts of the world basically can't live without those. But also it's the thing that saved my grandmother.

It's also about a sort of elite alignment, but this is rather different. It's not Schwarzmans. It's the public health authorities of these areas. It builds trust in really interesting ways and it opens up an entirely new arena, which I think the West should not be too insouciant about. We should be aware of the difference this is making.

“Everybody must take precautions against epidemics to smash the germ warfare of American imperialism!” [Source: Chinese Posters]

Chaoyang Trap Excerpt

This is a fantastic project. You should subscribe! An excerpt:

Caiwei: Podcasting is having a moment in China. In 2021, it’s not unusual to find “podcast lover” as a profile tag on Beijing Tinder—a result of the medium’s recent popularity. “Podcast lover” has now entered the hallowed lexicon of China Tinder Guys, joining such legends as “travel enthusiast,” “gym fanatic,” “crypto nerd,” and “cat owner.”

I was an avid Chinese-language podcast listener for three years before I started my own. In early 2018, a few sharp and witty women I followed on Weibo started Loud Murmurs (小声喧哗), a show that later introduced me to a whole new world. There was a strong “pirate radio” vibe to these early Chinese podcasts: emo philosophy guru Li Houchen’s FlipRadio(翻转电台), foreign correspondents Du Chen and Xu Tao’s East to West (声东击西), and tech writer Lawrence Li’s Yitian Shijie(一天世界) . At the time, podcasts were a “supplementary” medium—a niche to park your more experimental ideas in.

Calling yourself a Chinese-language “podcast lover” would not have made sense in 2018. There just wasn’t enough out there. But last year’s lockdown saw a huge surge in both creators and listeners.

I launched my podcast on the first day of 2021. When my trailer episode went online, I remember anxiously switching between every podcasting app to check for feedback. I lingered on Xiaoyuzhou FM (小宇宙), known as the most newbie-friendly podcasting app because of its sense of community. In the comments section, I saw one familiar name pop up: 七个梦 (qi ge meng, “Se7enDreams''). “I’m here for support,” he commented in Chinese, just a few hours after the episode dropped. He became one of my first subscribers.

I don’t know Se7enDreams personally, but he’s instantly recognizable in China’s podcasting scene. On Weibo, he’s known for his “podcasting notes,” which contain daily short reviews of recent podcast episodes. A living encyclopedia of Chinese podcasts, he calls himself an “omnivore podcast lover,” because there’s almost no genre that he does not listen to.

Investment advice, wuxia deep-dives, marketing insights, urban love stories—nothing escapes Se7enDream’s notice. From established prestige shows to emerging ones, he follows over 1,000 podcasts and has clocked over 3,500 hours on Xiaoyuzhou FM alone, an app launched barely a year ago. He is also one of the first advocates of the “podfaster lifestyle,” i.e. listening to each show at 1.5x playback speed (or higher).

When my second episode dropped, he appeared again. “来了,” he commented (“omw”), only minutes after the episode was online. He leaves a stream of feedback as he listens, marking time stamps in his post. He has another important mission: cuigeng (催更), a term used by avid fans to urge the creators of their favorite shows to put out new content.

For any content creator, having an attentive audience, generous with their feedback, is a blessing. And thanks to Se7enDreams, I became part of this lucky bunch. “First listeners'' like him are now a central part of what keeps Chinese podcasting moving. Through Weibo's hashtag “podcast recommendations” (播客推荐) and a namesake WeChat group, hundreds of podcast lovers (and some creators) practice a similar routine. They rush to the podcasts they love to show support. They scramble to new podcasts to “mark” their presence. They keep a log of their listening history to share in the community. They cuigeng creators for new content. They tend to the blooming podcasting scene with infinite tenderness, patience and care.

I was struck by the originality and vitality in these communities. In the WeChat group, anyone can share their favorite new episodes with a simple message, then a voluntary coordinator congregates entries into a daily, public Weibo post. On Jike (即刻, roughly a Reddit-Facebook hybrid), the kindness and heartfelt compliments are amplified through the popular hashtag #一起听播客 (“let’s listen to podcasts together”).

Although relatively mainstream, there’s a unique indie spirit in podcasting that is rare in other Chinese-language media formats.