Is Zuck right that AI lab security is a lost cause? How much AI technology has China already stolen? What will the consequences be if authoritarians win an AGI arms race?

In this week’s ChinaTalk YouTube documentary, we explore the Leopold Aschenbrenner thesis. Let us know what you think!

“Why are Chinese Government Workers So Average?”

One former bureaucrat has some anecdotes to share from their time working at a Chinese government office. This post was translated by Moly at Weibo Doomscroll:

Our workplace intranet’s system often has a bug where you can’t open up the status bar and it really affects people’s work. Before I came along, people would just reset their computers, eat some snacks, drink some tea, and chat while waiting for the computer to recover. Then I came along and discovered this problem while working, so I asked an IT friend how to fix it. From that point on, if anything goes wrong with any computers at work, it’s my job to fix it.

Here’s an example. Our workplace hires an outside contractor to make our PowerPoints, and no matter what the quality is, they charge a couple hundred RMB. But if one of us makes it on our own, no matter how well you do, all you get is a word of praise. Now, aside from your actual job, they’ll put you in charge of making all the PowerPoints. You have to work overtime to do them, and if you don’t do it well enough, people will complain and demand you make changes. Now everyone in the office claims they have no idea how to do PowerPoints.

A new guy came who knows how to take drone footage, posts vlogs to his social media every now and then. Then, our workplace wanted to make a promotional short video and put me in charge. I was asking photography studios for a quote when the boss suddenly remembered, “Hey, doesn’t so-and-so usually do this sort of thing? Let him try.” And I was like, “I dunno about that, drones can have all kinds of problems, and if it broke, we’d have to pay for it.” And the boss was like, “Oh, then never mind.” I don’t know who this asshole heard the gossip from, but he thought I was trying to put him down, so he went and recommended himself to the boss. Then, his drone fell into the artificial lake and nobody’s ever said anything about compensating him, and it’s been two years.

You don’t dare to be anything other than average. When I first got hired, my coworker saw my resume and asked me to help tutor their kid. I agreed because I thought it would be fun, and I ended up doing a great job, so now all of my coworkers want me to go tutor their kid. Ever since then, my line is, “It’s been so long since my graduation that I’ve forgotten everything.”

Swapped offices, and my boss was going to some diplomatic training, and as his secretary, I got so bored that I spent an afternoon translating the English curriculum and itinerary, and even preserved all the tables they had in the original document. Now, all kinds of diplomatic work is falling on me as the secretary. From that point on, “I’ve been to Europe, but I don’t speak any English.”

Our workplace hired some big-name ad company to make a fancy but entirely useless PowerPoint that doesn’t follow any of our formats at all. They were trying to run special effects made on a mac computer on MS Office, and it was all fucked up. I had to pull two all-nighters to basically do everything over from the ground up. And then, all kinds of important power points ended up coming my way. From that point on, “I don’t know how to use Chinese software.” Even now, I’m just an average dude who knows how to do data entry and maybe make a few phone calls and run some errands. I don’t know how to write any lesson plans, translate languages, do calculus, or make slide shows.”

The comment section:

This is so real…

All I can say is that this institution has fucked up management. How long has it been since you’ve had a government job?

See, it’s against nature to have no mobility in the government.

Why China’s New Cultural Confidence Is a Good Thing

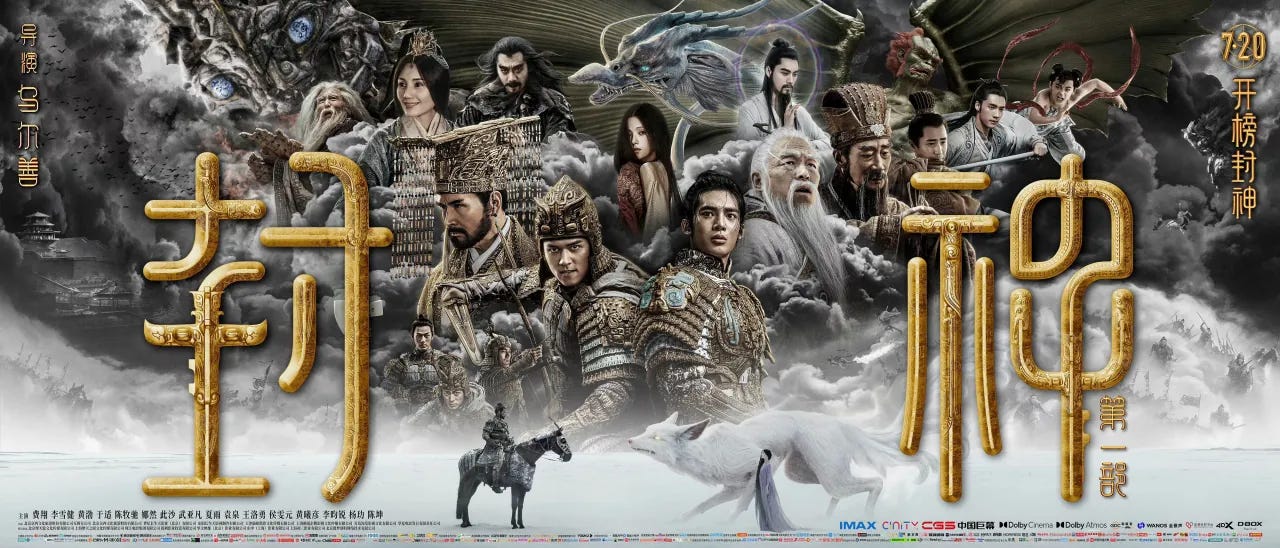

William Han is a Taiwan-born and US-educated writer and lawyer. He has a couple of screenplays bouncing around Hollywood. Today, he’s here to discuss the film Creation of the Gods I: Kingdom of Storms (streaming on Amazon Prime).

The plot may well be too complicated and unfamiliar for Western audiences to follow. And that may be part of the point.

The film Creation of the Gods I: Kingdom of Storms 封神第一部:朝歌风云 came out in 2023, after a three-year delay due to Covid, to nearly universal acclaim within China. It also cleaned up at the box office, becoming the 26th highest-grossing film to ever hit the Chinese market and out-earning Hollywood blockbusters such as Avengers: Infinity War and Avatar. Part II of the trilogy is now slated for 2025, with part III yet to be scheduled.

The film was made chiefly for the Chinese audience. It’s an epic historical fantasy based on ancient Chinese history. If you haven’t studied Chinese history, you’ll need some background to understand the movie.

From a Bronze Age War to a Fantasy Epic

In the 11th century BC, the Zhou state of western China was but a vassal of the ruling Shang Dynasty, until the Zhou revolted against the last Shang king. Led by their chief (the Lord of the West) and then by his son (the soon-to-be King Wu of Zhou 周武王), they defeated the Shang at the Battle of Muye 牧野之战 and established the Zhou Dynasty. It was a watershed moment in Chinese history — the Zhou would persist in some form for nearly eight centuries, and their fundamental impact on Chinese culture can be seen to this day.

That much is real history. Some of China’s most hallowed ancient texts attest to these events, but they are thin on details. Over the centuries, popular fictionalizations of history appeared to satisfy the folk imagination. Creation is officially based on two such fictionalizations.

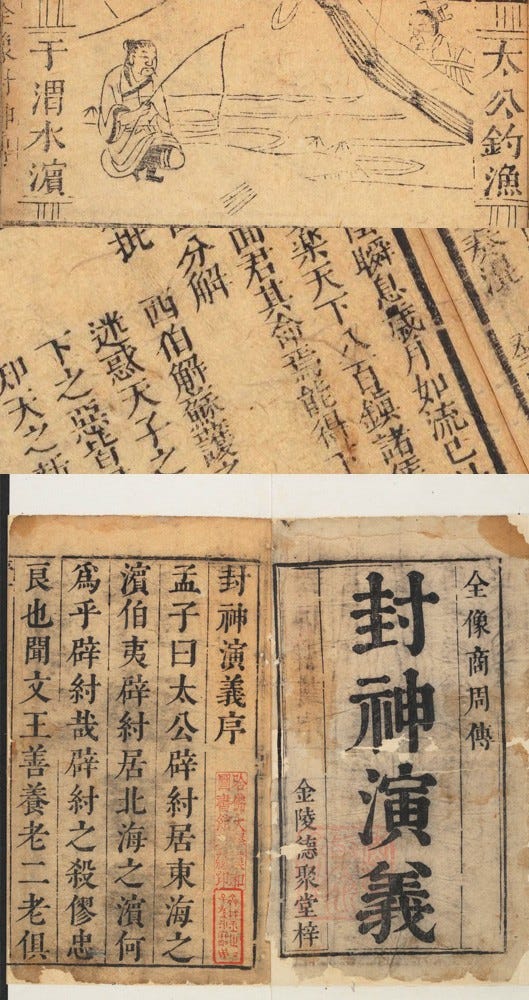

The first is a huaben 话本 (literally, “vernacular speech book”) — an outline for storytellers in the Song Dynasty. Just as premodern Europe had bards and rhapsodes, marketplace storytelling was a common art form in ancient China. This one was first printed during the Yuan Dynasty in the 14th century.

The second (and much more famous) retelling of this story is the 16th-century novel Investiture of the Gods 封神演义. Written during the Ming Dynasty, this novel organized the storytellers’ materials into a grand epic now known to every Chinese schoolchild. Thanks to Investiture, the tale of the great Shang-Zhou war grew beyond a military and political drama and became a supernatural fantasy.

The novel follows a cast of mostly fictional Daoist practitioners wielding magical powers, who fought on both sides of the war. When they were killed — or, in some cases, even when they survived to the end — these characters became gods (they were “invested,” if you will).

One example is Yang Jian 楊戩 (aka Erlang Shen 二郎神, the “Second-Son God”). As a powerful practitioner of Daoist magic, he plays a major role in helping the Zhou army in Creation and Investiture. Those who have played the newly released video game Black Myth: Wukong 黑神话:悟空 will already be familiar with him.

China Can Now Make Movies Like Hollywood

Of course, the filmmakers also took some additional liberties, but their adaptation has been a resounding success. Creation is one of a wave of mainland Chinese films in recent years displaying full command of the craft of commercial filmmaking. The 2017 Wolf Warrior II 战狼II showed that the Chinese film industry was now fully capable of making a Hollywood-style action adventure with a Chinese hero. It was vulnerable to charges of jingoism, but no more so than Mel Gibson’s The Patriot or Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor. The visually gorgeous 2023 feature Chang’an 长安三万里 demonstrated the industry’s mastery of animation, featuring the great Tang Dynasty poets and their verses.

As for Creation, I felt that the CGI was occasionally unconvincing, and the elderly character Jiang Ziya 姜子牙 sometimes approached the type of slapstick humor found in older Chinese films. But, in my opinion, it is easy to overlook these flaws.

Foreign film industries often struggle to master Hollywood-style screenwriting. The three-act structure — based on Aristotle’s Poetics and preached in Hollywood bibles like Screenplay by Syd Field and Story by Robert McKee — sounds simple but is surprisingly difficult to execute. Adapting classic novels with nonstandard structures poses an even greater screenwriting challenge. Peter Jackson confronted this difficulty and succeeded with The Lord of the Rings. Investiture is at least as complicated as LOTR, and the screenwriters and director of Creation have risen admirably to the occasion, making significant changes to the source material so that the story works for the screen.

By the Chinese and for the Chinese

But can a Western audience follow all this? Can a Western audience follow the motivations and actions of so many unfamiliar characters and their conflicts against an equally unfamiliar cultural and historical backdrop?

Another thing Creation and Black Myth: Wukong have in common — they don’t care whether Western audiences can follow what’s going on.

Both Creation and Wukong are Chinese products drawing on Chinese culture made primarily for Chinese consumers. Foreigners who want to come along for the ride are welcome, but they’re not the main target audience. The same can be said for the animated film Chang’an: of course foreigners aren’t going to appreciate Tang poetry the way the Chinese, who all grew up reading and reciting these poems, can.

The arrival of these products signals a new cultural confidence on China’s part. Just as Hollywood expects the rest of the world to know about Superman, it’s now up to you to get up to speed on Sun Wukong and the heroes and villains of Creation. And if you don’t have the energy or interest to do so — well, that’s your loss.

Diversity with Chinese Characteristics

Some have greeted Wukong’s release with claims that it lacks racial diversity — which seems churlish given that it’s about a monkey in a fantasy version of ancient China. And the claims clearly have more to do with ongoing culture wars in the West than with the game itself.

Creation, though, is very diverse. The film’s director is ethnically Mongolian, as is the actor who plays the future King Wu of Zhou. The actor who plays the Shang king is multiracial, having a Taiwanese mother and an American father: indeed, in English, his name is Kris Phillips. Naran, the Russian model and actress who plays the Shang king’s favorite consort Daji 妲己, is ethnically Buryat. The actor who plays Yang Jian is from the Yi 彝 minority ethnic group spreading from southwestern China into Southeast Asia. There is even disability representation on screen: the actor who plays the Lord of the West has lost his hearing due to cancer.

It’s hard to imagine greater minority representation within the Chinese context. Of course, Chinese filmmakers aren’t motivated by Western social-justice concerns. I have no inside information as to why the makers of Creation chose such a diverse cast — it could be purely a creative choice. It could also be an intentional move to present a multiethnic vision of China, in light of harsh international criticism of Beijing’s policies toward ethnic minorities.

The diverse casting, though, does feel appropriate given the source material. Both Investiture and Wukong’s source material Journey to the West 西游记, were written during the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty. This was a time of religious syncretism in China. All three major teachings — Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism — were seen as converging toward the same destination. The great Confucian thinker Wang Yangming 王阳明 (1472-1529) famously used the metaphor of a house: the three teachings, he wrote, were like three different rooms of the same house. Buddhism, the motivating force of Journey to the West, had been a foreign import from India. But Chinese people saw this fact as irrelevant. Every race everywhere, Confucian intellectuals argued, must’ve been endowed with the same capacity for moral reasoning. If sages in India had figured out a way to Enlightenment, then we should gladly take advantage of it.

Although the Shang-Zhou war occurred centuries before the rise of Daoism and Buddhism, Investiture takes pains to acknowledge the latter’s wisdom for the benefit of its Ming Dynasty readers. Several supernatural characters are presented as future Buddhist deities, with the novelist explicitly noting that so-and-so immortal would later turn to “the Religion of the West,” no less valid than the teachings of China. Investiture thus reflects the ecumenical view of the world prevailing in Chinese thought at the time. Indeed, around the same time, Chinese intellectuals welcomed Jesuit missionaries like Matteo Ricci into their midst, believing that Christianity must also serve as simply another path to Truth.

Confidence Is Good, Actually

Historically, then, the Chinese have often been receptive to foreign ideas and careless of their foreign origins precisely when they are most confident in the strength of their own civilization. That version of China is the one I would like to see today.

Unless that’s Pollyannaish. Maybe that idealized China, confident and therefore ecumenical, is as much of a myth as Sun Wukong or Investiture. But I prefer not to think so. And films like Creation of the Gods I, along with games like Wukong, show a growing cultural confidence that is one step in the right direction.

Who knows? Maybe even Americans can be confident enough in their own culture to be receptive to Chinese films, games, and stories. Wouldn’t that be something?

Alexa Pan — Chinese Art Rock Song of the Week

“The Peacock Flies Southeast” 孔雀东南飞, by Wood Pushing Melon 木推瓜.

This song is for the art rock fans and ecstatic dancers. Formed in 2000, Wood Pushing Melon’s lineup hails from far corners of China: Jilin (northeast), Guizhou (southwest), Hainan (southernmost), Xinjiang (northwest). After a brief stint in Beijing’s crib of rock legends, Shucun, they went on hiatus and reunited in 2015, recording four studio albums since. Often compared to King Crimson and Frank Zappa, Wood Pushing Melon covers an eclectic range. Vocalist Song Yuzhe 宋雨喆 had spent his free decade blending ancient China, central Asia, religious, and contemporary music in his personal project Dawanggang. These influences feed into the Wood Pushing Melon’s sound: world music and folk fusion meets progressive and art rock.

“The Peacock Flies Southeast” plucks its name from a celebrated ancient poem describing a tragic romance. Under Wood Pushing Melon’s direction, it is a twelve-minute ballad with no words. In this musical ensemble iridescent as the bird itself, rhythm is the only constant; everything else — flute, organ, synthesizer, grating or rattling percussion, operatic voice flourishes — comes and goes in flushes (I particularly enjoy the banging piano chords and martial arts-like vocalizations around 6:50). For all the highlights in its musical fabric, I find the song a nice piece of ambience to work or relax to as well.

If you enjoyed this song, check out their first album.

Incompetence and a focus on “barely good enough” in public administration is hardly an exclusively Chinese characteristic. I’d suspect you’d find similar stories from public servants around the world, including the us and Europe.