I’ll be in Tokyo in late March. Do reach out — it would be great to meet up!

I’d also love some book recommendations on the Meiji Restoration, postwar political history, and Buddhism in Japan.

Uncle Sam Wants You for AI Legislation!

We’re at a really exciting moment around AI policy where there’s a bipartisan appetite to do things so that clever ideas can quickly gain traction. I’ve found engaging as an outside expert in the legislative process to be one of the most rewarding ways to spend my time — and FAS is great at on-ramping subject-matter experts on how to take an idea and put it on the path to actually existing in the world.

The Federation of American Scientists is hosting an AI Legislation Policy Sprint to identify, develop, and publish a set of AI-focused policy ideas that could be implemented by Congress. Action-ready proposals are only 1,000-3,000 words. The deadline to apply is March 22.

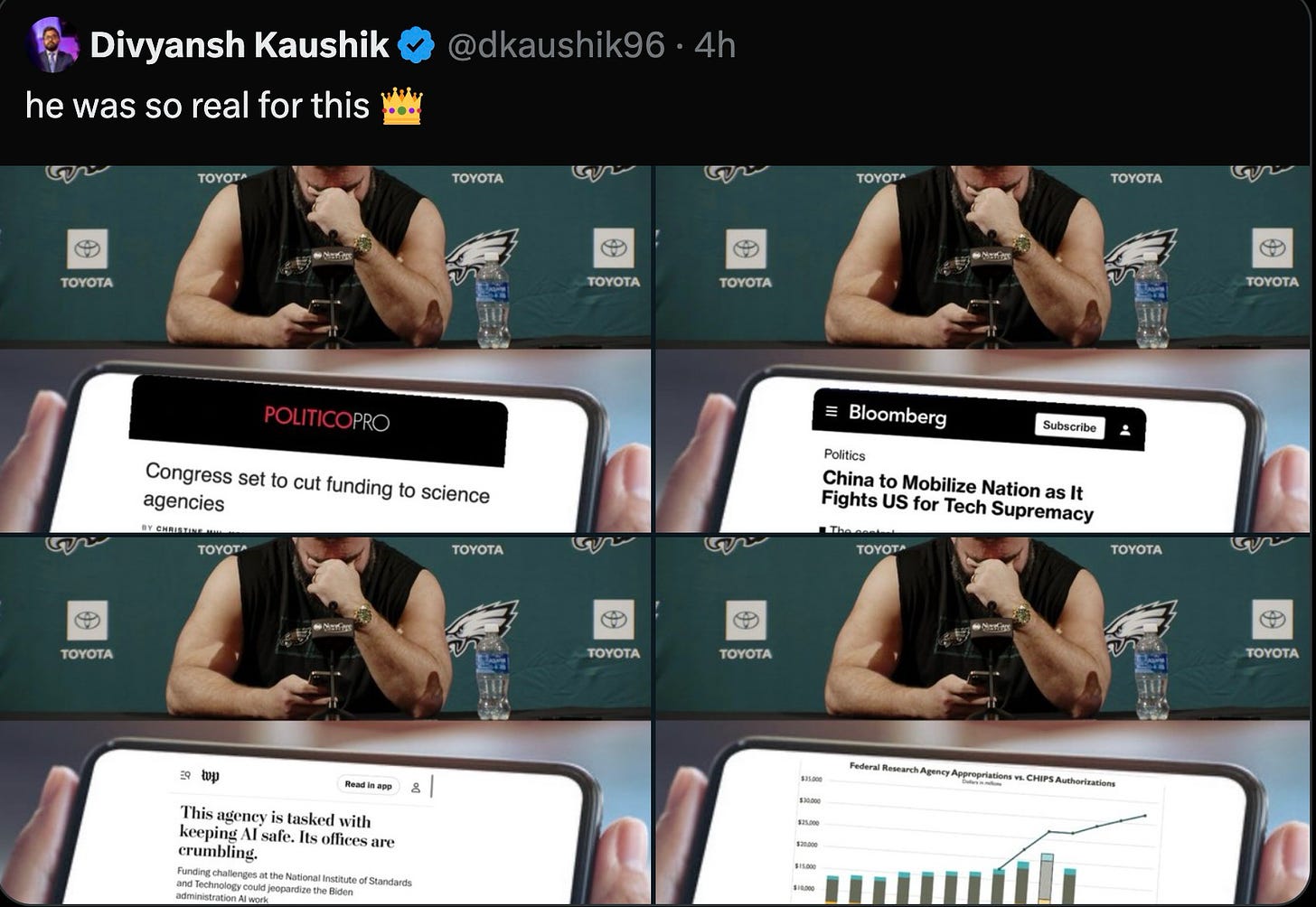

For some inspiration, check out the podcasts below I did with Dan Correa, FAS’s CEO, and Divyansh Kaushik, who is leading this AI legislation sprint. Feel free to bug him with DMs to stress-test your idea before writing it up!

Tweets of the Week

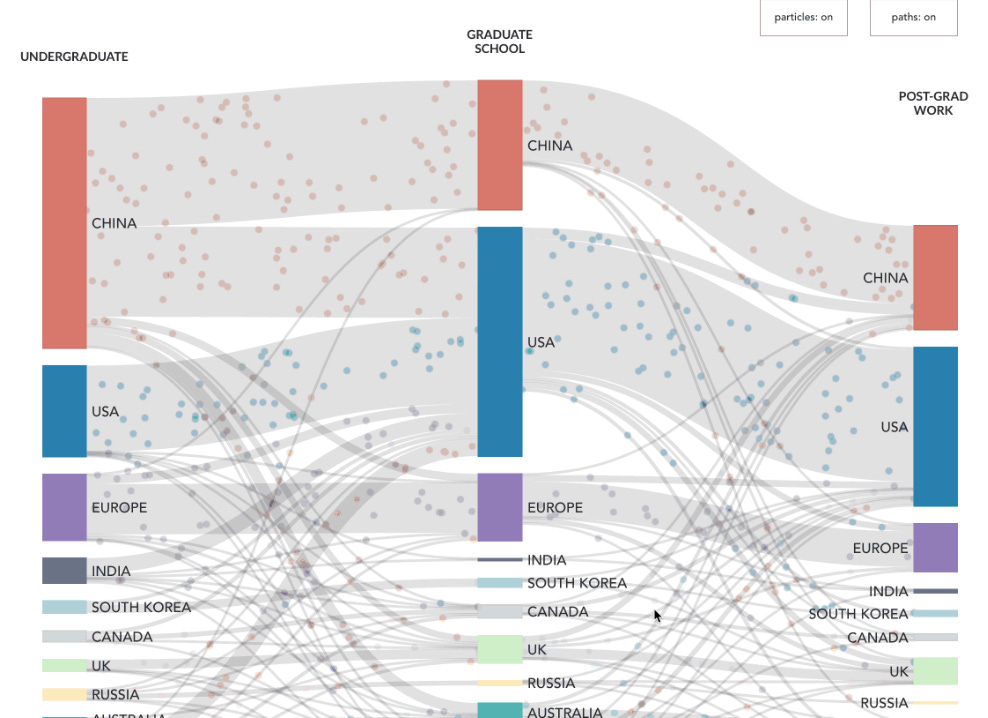

A new MacroPolo AI Talent Tracker dropped! Full link here.

BIS wishes it were Sardaukar…

Speaking of, I was very bummed the CHIPS Act didn’t opt for this release strategy…

After Xi

The Two Sessions is cool and all, but the biggest question in Chinese politics is one that is getting approximately zero official airtime! Neil Thomas of the Asia Society wrote a fantastic paper exploring some potential succession dynamics. See below for an excerpt, and for more check out this podcast I did with Richard McGregor about his report on the topic.

Xi’s Succession Is Unlikely to be Orderly or Predictable

Xi Jinping’s successor is unlikely to be as powerful, regardless of how the succession occurs. The later a successor is appointed prior to Xi’s departure, the weaker they are likely to be. If Xi appoints no successor, different networks of Xi followers are likely to struggle over the top job.

Much of this uncertainty stems from the Party’s lack of clear succession mechanisms. Mao Zedong tapped Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping ousted Hua, Deng elevated Jiang Zemin, Deng anointed Hu Jintao, and then Jiang supported Xi. It is backroom politics through and through.

Xi’s selection as Hu’s heir apparent after the 17th Party Congress in 2007 was reportedly helped by his victory over Li Keqiang 李克强 in a straw poll of senior officials. But Xi ended intra-Party voting after 2012 in favor of choosing new leadership lineups through elite interviews.

If Xi picks a successor, he will likely go through the motions of an orchestrated but seemingly rigorous selection process to bolster the legitimacy of the chosen cadre. He could also embed the choice in authoritative Party documents and make other leaders declare their assent, making it more difficult (or at least more awkward) to turn on the successor.

If Xi experiences a sudden health incident, there is no way to know what would happen next. Article 23 of the Party Charter simply states that the general secretary is elected by a plenum of the Central Committee and must be drawn from the ranks of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). Xi’s successor would likely — but not necessarily — be a current PSC member, because a plenum could technically add a new member and then make that person the general secretary.

But how would the Central Committee even convene a plenum without a general secretary? The Party Charter says that the Politburo is responsible for convening plenums, but it is the general secretary who is responsible for convening the Politburo. This legal conundrum lays bare the importance of informal power in determining political outcomes in Beijing.

History can be a guide to the future…

The best account of the transition from Mao to Hua to Deng is Joseph Torigian’s book, Prestige, Manipulation, and Coercion — the title of which sets out the three key factors that matter for succession struggles in Leninist one-party regimes.

[Hear Joseph on ChinaTalk talk about his book, below]

First, the importance of prestige means that victory often depends more on interpersonal authority than policy differences or economic interests. If we apply this theory to the case study of Xi’s succession, we can examine the different networks that connect senior leaders below Xi.

Here, two potential rival networks of Xi loyalists seem to be emerging:

The first is a group of officials connected to Fujian Province who either got to know Xi when he was a local leader there from 1985 to 2002 or worked with him there afterward; these individuals include Xi’s chief of staff Cai Qi 蔡奇 and new economic czar He Lifeng 何立峰.

The second is a group of officials with similar ties through Zhejiang Province, where Xi was leader from 2002 to 2007. Atop this group is Li Qiang 李强, who, as premier, leads the work of the ministries in the State Council.

We know little, however, of the personal relationships between top leaders or the possible coherence of such networks without Xi. And the longer Xi rules, the more of his longtime associates will retire into “Party elder” status and vie for post-Xi political influence with emerging “seventh generation” leaders born in the 1970s.

Second, victory depends on coercion — that is, gaining the support or control of the military, police, intelligence services, and other security-related ministries to enforce the succession. For Xi’s succession, we might look at which networks of Xi followers appear well-placed to leverage China’s centers of coercive power.

One could argue that the Fujian network is best placed to deploy coercion. It likely includes top security official Chen Wenqing 陈文清 and Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong 王小洪, as well as newly empowered Central Military Commission (CMC) Vice Chairman He Weidong 何卫东 and his fellow CMC member Miao Hua 苗华. Cai Qi’s remit includes the Central Guard Bureau, which is responsible for the security of Party leaders. Chen Yixin 陈一新, the minister of state security and a close colleague of Xi and Li Qiang in Zhejiang, could emerge as a rival powerbroker.

The third key factor, manipulation, means victory depends more on the ability to control the process of selection rather than playing to a defined “selectorate.” So while rules can be bent or even ignored, the appearance of legality, legitimacy, and stability is still important.

If Xi were to depart suddenly, who could best manipulate the process of selection? The situation would be extremely fluid, but a case can be made that Cai Qi — or someone in his position in the future — would play a role. Cai has an unusually central role in managing internal Party affairs as a PSC member who leads both the Central Secretariat and the General Office of the Central Committee. He would likely be the first senior leader to learn of any developments regarding Xi’s health or decision-making.

The Party Charter produces the legal conundrum discussed earlier, but Article 23 also establishes the Central Secretariat as the working body of the Politburo. In the absence of a general secretary, Cai could argue for a generous interpretation of this article that allows the Central Secretariat to call a Politburo meeting that then convenes a plenum.

An aspiring leader would not need universal support to pull this off. According to Article 25 of the Central Committee Work Regulations (which the General Office has the authority to interpret), only a majority of Politburo members must be present to hold a meeting. So, thirteen Politburo members could convene a plenum. Article 24 says that a majority of Central Committee members then need to be present to hold a plenum. That is 103 members. Just half of those members are then needed to pass a decision. Thus, following the Party’s own rules, one would theoretically need the support of only 52 Central Committee members to appoint a new general secretary. (This minimum condition assumes that the 52 Central Committee members include 13 Politburo members.)

Executing such a plan, however, would require many other things to go one’s way, including control of the propaganda system, support from the military and security services, and rivals too weak or disorganized to challenge the move. Moreover, any new leader would prefer to come to power with the façade of unanimous support within the Party.

Another wildcard could be the vice president. Article 84 of the state constitution says that if the presidency becomes vacant, then the vice president becomes president. While the largely ceremonial presidency is easily the least important of Xi’s three main roles, the new officeholder would hold constitutional powers to promulgate laws, appoint state leaders, grant special pardons, declare a state of emergency, and even declare war and issue mobilization orders.

The constitution, however, says that the president exercises these powers “pursuant to decisions of the National People’s Congress and the National People’s Congress Standing Committee [NPCSC].” Still, an accidental president could still try to affect the succession process by blocking government action. If they collaborated with a powerful NPCSC chairman, they could use lawfare, new appointments, or emergency decrees to gain more leverage.

These thought exercises are not concrete forecasts, however, and they are most valuable as illustrations of the uncertainty and unpredictability of succession politics within the Party, especially if there is a sudden succession crisis or a move to depose an anointed yet unpopular successor.

This Week from Weibo Doom Scroll

The campaign video from Valentina Gomez (running for Missouri Secretary of State) is getting a lot of attention, the one where she promises to shoot down Chinese spy balloons and poses with a … gun? Of some kind?

Comments say, “If this is the level their politicians are at, then I can rest easy.”

“When she fired, I thought the gun exploded or something XD”

Home buyers are getting more and more insane.

Nobody wants number 4, so a lot of developments don’t have 4, 14, or 24.

They don’t want 6 and 13 either, because apparently they’re “unlucky” in the west. I don’t know what kind of busybody the western demons are, though, that they’d come bother homeowners in China…

8 used to be the most popular, but now it’s not anymore, because “seven up eight down” [七上八下, an expression from Water Margin 水浒传 used to describe uneasiness, worry, anxiety], so your career will go down with “eight”…

The most ridiculous is that people now think 18 is unlucky, too. People used to love 18 because it means “destined for fortune.” But now they’re talking about 18 layers of hell. And I’m all like … even if there are 18 layers to hell, it would be 18 floors below ground, right? What would it have to do with the 18th floor above ground?

Comments say, “Lol, the 4 and 18 debuff can stack, too. If your building doesn’t have the 4th and 14th floor, then the 20th floor might actually be the 18th floor.”

“But if hell has 18 layers, then wouldn’t everything from 1-17 also be unlucky?”

“7th floor really is popular, though, with this ‘seven up eight down’ thing.”

Question: “What’s the most incomprehensible logic you’ve seen from Chinese parents?”

Answer: “What I don’t get the most is that a lot of parents will demand that their children not cry even while they’re beating them. The more they cry, the more the parents beat them. The more the parents beat them, the more they cry. I literally don’t get it. What’s the point of forcing your children to not cry?”

Comments say, “Growing up for most people: bearing with pain —> understanding pain —> creating pain.”

“I’ll answer. My childhood was like this. I got beat by my mom all the time. Every time something went wrong in her life, she’d vent by beating me. I wasn’t allowed to cry. She knew she was abusing me, so she had a lot of cognitive dissonance. If I don’t cry, she won’t feel like she’s properly vented. But if I cry loudly, she’s worried the neighbors will judge her. So she’d beat me while demanding that I don’t cry. But if I actually succeed at not crying, she’ll beat her harder. (She used a thin bamboo stick. It hurt a lot.) She would beat me until I was rolling around on the floor, until she’d gotten off on it.”

“So long as there’s no noise, the neighbors will think you have a perfect family.”

“Nah, it’s just because crying is annoying to listen to — but they won’t learn anything if you don’t beat them. They’ll learn their lesson after a beating, and you don’t let them cry because you’re already annoyed. Listening to a kid cry will just make you more annoyed.”

Hey, are there any Chinese-made cartoons with a female protagonist?

My kiddo said that America has Elsa, and she has magic, and she’s a princess, and my daughter likes magical princesses. Are there any Chinese cartoons with female protagonists or a predominantly female cast? I want to change her tastes.

I’ve thought about it, and can’t come up with anything except Mulan?

Comments say, “Well, there are plenty of Japanese cartoons with female protagonists, but it’s all about the male gaze.”

“I grew up watching anime, so I had no idea that there aren’t any Chinese cartoons with a female protagonist?? That’s completely incongruous with my perception of women’s status. Japan has Sailor Moon and Phantom Thief Jeanne and Chibi Maruko-chan and countless others.”

“Well, several came to mind — the Small Giant, Mona the Vampire, etc. — and then I realized none of them is from China. China only has, like … I dunno, Diamond Sisters? And it’s only a spin-off of the Diamond Brothers. Honestly, does a cartoon even exist in China with a female protagonist that isn’t covered in stereotypes (pink, frilly dresses, high heels, long eyelashes, dolls, bows, etc.?) Japan at least has Spirited Away.”

“Yeah, we’ve got Little Zhuoma 小卓玛, all about a Tibetan little girl, with a plot line mostly about the hunting and protection of Tibetan mountain goats.”

“Yeah, it’s hard to think of one where the girl is the primary protagonist. Most of them are just a companion that shows up as a part of a boy’s journey, like the dragon girl in Nezha’s story. Look at The Twelve Kingdoms, or Moribito — they actually have a solid plot line and character arc about girls.”

“If there aren’t any female protagonists, I’ll create them myself. I grew up watching Nezha as though he was a girl. Gosh, you should’ve seen how much I freaked out the first time I found out he was supposed to be a boy.”

If you make it to Kyoto on the trip, I’ll buy you a beer.