What can American diplomacy do to head off an invasion of Taiwan?

To find out, ChinaTalk interviewed R. Nicholas Burns, Biden’s Ambassador to China, whose diplomatic career spans 35 years and 8 countries.

Listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

We discuss…

Lessons from Kissinger’s career,

How China’s negotiating tactics are so different from those of the Soviet Union,

Great power responsibilities, and whether Chinese leaders truly appreciate the reputational costs of helping the Russians and the Houthis,

How talking can lower the risk of WWIII.

We have a podcast! Listen to this interview on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

The Art of Diplomacy

Jordan Schneider: Ambassador Burns, welcome to ChinaTalk.

R. Nicholas Burns: Thank you very much. Long time coming, Jordan. I’m a big fan of yours. I’m glad we could schedule this before I leave China next week.

Jordan Schneider: When you co-authored a book on Kissinger’s negotiating style, you wrote about the diplomat who, among many other things, probably had the most fun negotiating in U.S. history. As he described his Chinese interlocutors, he said…

“Mao, Zhou, and later Deng were all extraordinary personalities. Mao was the visionary, ruthless, pitiless, occasionally murderous revolutionary; Zhou, the elegant, charming, brilliant administrator; and Deng, the reformer of elemental convictions…”

Do you ever get bummed out that the Chinese officials you were destined to deal with are so much more boring?

R. Nicholas Burns: I don’t think they’re boring! In fact, we have animated discussions. When I was a professor at Harvard, I co-authored a book on Henry Kissinger called Kissinger the Negotiator with two other professors. The main author was Professor Jim Sebenius of Harvard Business School. We spent hours with Secretary Kissinger in New York and in Cambridge at Harvard. He told us that while hundreds of books had been written on him, no one had ever written a book about his negotiating theory and style.

Subsequently, when I was nominated to be ambassador, I spoke to him multiple times before I came to China and then multiple times while I was in China. This extraordinary thing happened when he was 100 years of age — he came here to Beijing in the summer of 2023 for five full days. I met him at the airport, and he was ready to go. I really benefited from his historical perspective on the arc of the U.S.-China relationship and what it’s like to deal and negotiate with the Chinese.

Many of the principles he developed based on his conversations with Mao, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping remain true today because the Party is still the primary agent of Chinese power. In my conversations with the Chinese leadership — I’m having a series of outgoing meetings with ministers here and other senior officials — these are challenging discussions. As a career diplomat, I have a healthy respect for how well-trained these Chinese diplomats are. They’re really worthy adversaries, and they’re thoughtful in many different ways. I’m having big-picture discussions this week about where this relationship is heading. They’re not boring.

Jordan Schneider: After taking Nixon to China, Kissinger reflected on how the U.S.-Soviet relationship changed:

“Prior to my secret trip to China, Moscow had been stalling for over a year on arrangements for a summit between Brezhnev and Nixon . . . then, within a month of my visit to Beijing, the Kremlin reversed itself and invited Nixon to Moscow.

“Suddenly, the Moscow summit was not elusive. . . . Other negotiations deadlocked for months began magically to unfreeze[.]”

Today we’re in a period in U.S.-China relations where Beijing is not super interested in negotiating anything necessarily to the level that the U.S. and Soviet Union achieved over the course of détente. What are your reflections on that?

R. Nicholas Burns: Many people have raised this with me in conversations — is there an opportunity that we in the United States could look at the current situation in our fraught relations with both the Russian Federation and China and do a reverse Kissinger? The situation we’re in today in 2025 is completely different from what Kissinger and President Nixon faced in ’69, ’70, ’71 as they began to think about the opening to China.

You’ll remember, Jordan, that Mao began to distance himself considerably from the Soviets in the very late ’50s. By the early ’60s, he had kicked the Soviet advisors out. They’d gone on to develop their own nuclear weapons program by 1964. What Kissinger and Nixon did was historic, but they had an opening that is certainly not present today.

The fundamental question for the Chinese is this: they continue to say — and many of them believe — they want to be agents of world order, they want to be responsible, they want to respect the international system.

But they’ve got a choice to make because they’ve aligned themselves with agents of world disorder.

They’ve aligned themselves with Russia, with its brutal invasion of Ukraine, and the Wagner Group sowing mayhem in West Africa. Iran, now weakened thankfully, but for 40 years has been one of the biggest problems in the Middle East and a country threatening to become a nuclear weapons state. North Korea is one of the biggest agents of disorder in the world today.

There’s a loose alignment between China and those three countries, and they can’t have it both ways. At some point, they’re going to have to choose. Obviously, we would hope that the Chinese would want to be a more responsible country than they have been on some of these major issues of global order and the future of the international system.

One good example that leaps out to me, because I’ve lived it here since late February of 2022, is that the Chinese say they’re neutral in Russia’s assault on Ukraine, but they haven’t been neutral. Hundreds of Chinese companies have been giving very important dual-use technologies to the Russian war machine. The Chinese deny that’s happening, but it is happening, and we’ve sanctioned those companies.

Another example is the cyber aggression by China against the United States, which Director Wray and other American officials have been talking about publicly and how objectionable this is. These are the questions that we Americans need to put before the Chinese leadership. I’m doing that. I’ve been doing that for several months, as have Jake Sullivan, Secretary Blinken, and others. That’s what the Chinese need to really think about as they think about their own position in the world.

Jordan Schneider: In the book, you discuss how Kissinger, when at an impasse where the other side didn’t necessarily see your point of view, would start playing 4D chess, moving things around on other parts of the global chessboard. The dream is to get to a direct bilateral dialogue of the sort that Dobrynin had with Kissinger, where he says, “I can say with certainty that had it not been for my channel with him” — where they’re doing all this Marilyn Monroe-style sneaking into the White House — “many key agreements on complicated and controversial issues would have never been reached and dangerous tension would not have been eased over Berlin, Cuba, and the Middle East.”

The question to you is, if the stage is not set for that real dialogue where both sides are interested in really grasping, really trying to push forward solutions on the biggest, most difficult questions, what can dialogue do?

R. Nicholas Burns: Dialogue does two things, and we do believe in it.

First, it’s the daily practice of diplomacy. There are a thousand issues, metaphorically, in the U.S.-China relationship. We deal with an extraordinary range of problems with China. Conversations from my embassy to the Chinese Foreign Ministry and other parts of the government here happen every day on all those issues. They take place in Washington with the embassy from the PRC as well. That’s one order of business you’ve got to have.

We learned in this relationship — and I certainly learned — what happens when you don’t have daily connectivity. After Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022, the Chinese very unwisely and objectionably shut down eight channels of communication. We went for several months until November of 2022 with not a great ability to contact them. I was having meetings with the Foreign Ministry, but we didn’t have our cabinet engaged.

In early 2023, when that strange balloon drifted across the national territory of the United States in a strange Orwellian way, the Chinese blamed it all on us when the President rightfully ordered the balloon shot down. We went through another three to four months of no appreciable contact. That’s a dangerous situation when the two strongest countries in the world, two strongest military powers in the world, where our militaries are juxtaposed very closely to each other in the East and South China Seas, are unable to have conversations if there’s an accident or a misunderstanding.

What we’ve tried to do over the last 18 months in re-engaging with the Chinese is to establish reasonable, sustained conversation about diplomacy. It’s identifying problems — sometimes you can’t find a solution, but you can manage the problem and you can disengage or sanction them, whatever the answer is. You just can’t afford in the modern age to have a situation where we’re not talking on a daily basis.

This second part is very meaningful — can you have thoughtful conversations that are not tit-for-tat and trying to one-up each other or score points? Can you try to investigate what’s behind that policy that you’re running? Why are you doing it? What are the limits of it? What are the boundaries of it?

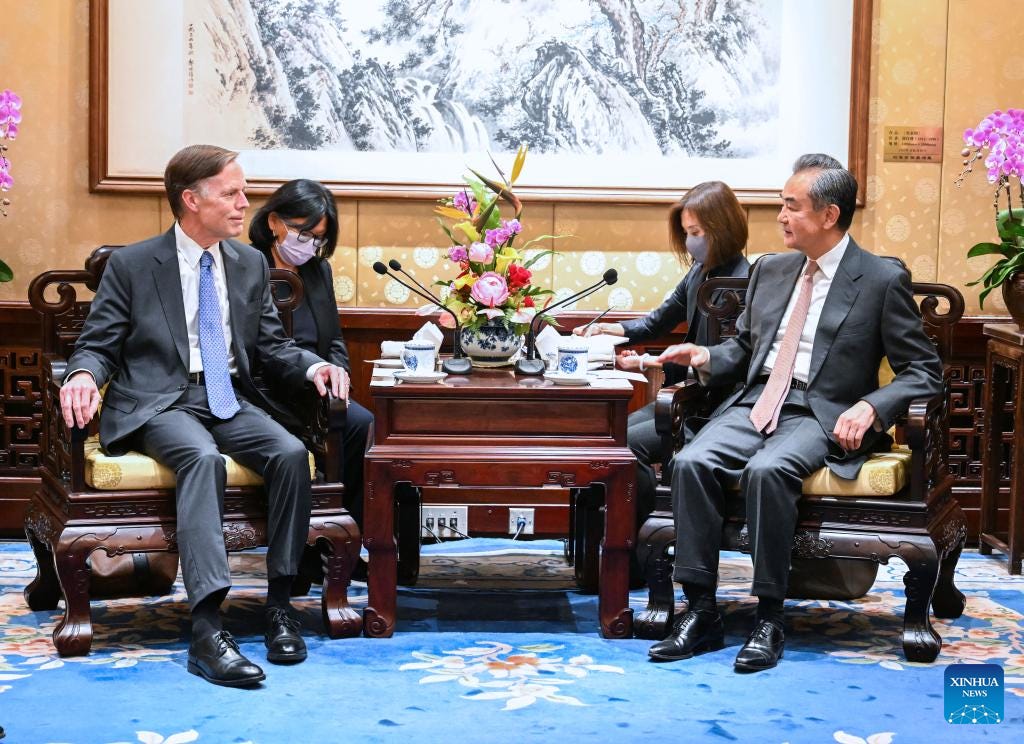

We’ve begun to have those conversations. I’ve been with Jake Sullivan in Malta and in Bangkok and here in Beijing over the course of the last year and a half in two-day meetings each of those times with Wang Yi, who is the Foreign Minister of China but also has a more senior position — he’s Director of the Foreign Affairs Commission. In 12-15 hour conversations in each of these settings, Jake and Wang Yi have been talking in a much more introspective way. Secretary Blinken has had those types of conversations with Wang Yi as well. It’s harder with the military here because they’re more closed, they’re more opaque. But it’s important to have those conversations as well. It’s part of diplomacy between two superpowers.

Jordan Schneider: My bellwether is Wang Yi coming on ChinaTalk. When that happens, then we’ll know we’re really ready to get down to business.

Michèle Flournoy said in an interview I did with her a few years back:

“Risk reduction measures and crisis communications are things we tried even when there was a lot of dialogue back in the Obama administration. We tried to push them on hotlines or incidents at sea agreements. These were mechanisms we had with the Soviets. The Chinese have never been willing to talk about that. They just say, ‘You seem to really want this, so give us something else like stop talking about Taiwan.’ And of course that’s never going to happen.”

I’m curious for you to reflect more broadly on the relationship between talking and the probability of great power conflict. People refer back to World War I where great powers sleepwalked into war. But there’s also World War II, where the U.S. and Japan were talking the day of Pearl Harbor, where Hitler and Stalin were talking the day before Operation Barbarossa, where Hitler and France were talking before Czechoslovakia. What are your thoughts on that?

R. Nicholas Burns: This is a central question. We are competing with China. The answer to the question, and it’s structural, is that we’re global rivals. It’s going to continue. One of the tests of this relationship is, can we compete and yet do so in a way that doesn’t elevate the probability of a conflict between us? Our job is to diminish the probability of a conflict.

I remember the EP-3 incident in the spring of 2001 — I was not involved in China affairs then. We had an air collision between Chinese and American military aircraft, which led to the death of the Chinese pilot and led to the impoundment of our plane and our crew. One of the things that we’ve worried about, and I certainly have worried about in my nearly three years here, is can we handle that kind of crisis in the U.S.-China relationship? Can we have the kind of higher level connectivity so that if 24-year-olds collide in ships in the Spratlys or the Paracels or the Senkakus, senior people can intervene and diffuse the crisis?

We’ve worked on it for a long time. The PLA wouldn’t talk to the senior levels of the military. During the balloon crisis, I was a primary port of contact with Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng, who’s now the Ambassador of the PRC in Washington. What I was saying to him was we need to get our senior military leaders talking about this incident, and they refused. President Biden pushed this at the San Francisco Summit and again at the APEC Summit in ’23 and ’24 with President Xi Jinping. The result is the Chinese have agreed and we’ve begun to have those higher-level military-to-military contacts. Admiral Sam Paparo, a very gifted leader who’s the head of Indo-PACOM Command in Honolulu, has had two meetings with the Southern Theater Commander of the PLA just this past autumn.

That’s just the beginning. We’ve got to have those kinds of contacts so that in the eventuality of a profound misunderstanding or an accident, we can intervene to keep the peace. Strategically we’ve got to compete with China, but we also have to live with China. We’re not trying to head this into a brick wall, we’re trying to avoid the brick walls. That gets to the heart of your question: do you have enough connectivity at the senior levels to do that?

We’ve begun to do it with Jake and Tony Blinken, Secretary Blinken with Wang Yi, and certainly with Admiral Paparo. We’d like to be able to get our Secretary of Defense, our Chairman of the Joint Chiefs — they have talked to their Chinese counterparts — but obviously elevate the conversation to them. As the American Ambassador here, one of my fundamental jobs is to establish these relationships of my own with Chinese leaders so that I can — and my successor obviously can — play a role in this. The central question is: how do you compete vigorously and at the same time keep the peace? That is what is at stake here for the United States and China.

Jordan Schneider: The key question is — even if they were really excited to talk about military matters X, Y, and Z, there’s the World War II analogy, where you can be doing one thing with one hand and be planning very dastardly deeds with another.

R. Nicholas Burns: Listen, you have to have your eyes wide open at all times in a great power relationship.

I’ve been asked a lot, “Are you trying to gain the trust of China?” or, “Do you trust China?”

My answer to is always the same — it’s not a question of trust. It’s a question of judging the Chinese by what they do, not just what they promise to do or what they say publicly or privately. Judge them, and call them on their actions, whether they’re positive or negative.

What we have been doing here on a practical basis is basically running a relationship that is, in my mind, about 80% competitive. I spend about that amount of time on the competitive edge of this relationship, whether it’s our military differences in the Indo-Pacific, our technology differences, or human rights differences. A generation ago, when I was Under Secretary of State for Condoleezza Rice, our ambassador, Sandy Randt — and he was a really good ambassador — probably was 75-80% engagement. I’m now 20% engagement. You have to judge these countries by what they do, and obviously we have plenty of disagreements strategically and tactically with what the Chinese are doing.

Jordan Schneider: You said on a podcast that, growing up and even into the ’80s, you never imagined the USSR would disappear. Then all of a sudden it did. You also noted that you didn’t really like Reagan a lot in your 20s but, in retrospect, came to respect his stance on the USSR. There’s the Gallagher-Pottinger thesis today, and I want to give them the full quote because people say “regime change,” but it’s a little more nuanced than that: “The U.S. shouldn’t manage competition with China. It should win it. What would winning look like? China’s communist rulers would give up trying to prevail in a hot or cold conflict with the United States and its friends, and the Chinese people, from ruling elites to everyday citizens, would find inspiration to explore new models of development and governance that don’t rely on repression at home and compulsive hostility abroad.” What’s your reflection on the Reagan-inspired Gallagher-Pottinger playbook for U.S.-China relations today and into tomorrow?

R. Nicholas Burns: I joined the State Department as an intern 45 years ago in 1980, and then full-time as a diplomat in ’82, so I served in President Reagan’s administration. President Reagan was an absolutely key figure in preparing for the end of the Cold War, which, by the way, we didn’t expect. I was actually at the White House between 1990 and ’95 at the NSC, working for H.W. Bush and then Bill Clinton. Right up until a month or two before the fall of the Soviet Union — really, it was only until October, November of 1991 that we thought the Soviet Union would collapse. It was that late, and that was a judgment of our entire government.

This is a very different situation. While it’s tempting to compare that old Cold War — and I was part of it in the early stage of my career — to this time, China is infinitely more powerful in its own self, in its own state, its economy, its technological base, its science and technology expertise, its incredible universities and research institutions — far stronger than the Soviet Union. That has to be said first.

I have a lot of respect for Mike Gallagher and I’ve talked to him a lot about these issues, as well as Matt Pottinger. They’re really smart guys, and they’re trying to be thoughtful about this relationship. I would pose a couple questions because I don’t necessarily agree with what they’re saying.

The first question is — how are the Chinese going to react to a strategy where the Americans say we’re going to win this competition? That implies that China is going to have to change its system of government that’s been in place since October 1, 1949. In this party-central state here in China, you’ve got to calculate how the other state is going to react in order to pursue a policy like this.

The second question is — how are the allies going to react to this? If we have a stated policy that we’re going to win now, people in the international system will think that means the kind of victory we had on December 25, 1991, when the Soviet Union imploded and disappeared. What does that pose to Japan, to the Philippines, to Australia, to India out here in the Indo-Pacific, to the NATO allies and EU partners? Because they’re a big part right now of our ability to try to limit the options that the Chinese have around the world.

What will countries in the Global South think of that strategy? Does it pay off for the United States? Does it win us more strategic weight in our relationship with the allies? Can you bring countries along in a strategy like that? I have real doubts that you could do that.

The final question is — what does it do to this really uneasy balance of trying to get certain things done where our interests are aligned? What does it do on issues like climate change, on fentanyl — where we are beginning to see the Chinese help us, but they need to do a lot more — and what happens on the military-to-military side? Would they shut down all communications with us?

You have to think through the upside and downside. I have great respect for those two guys, and we need this type of fermentation and dialogue in our own system in the United States. I just don’t agree with what they put forward — respectfully — in the Foreign Affairs article.

Jordan Schneider: Let me challenge one of your contentions. You just said China has had one system of governance since 1949, but we’ve had many different eras. Yes, the party has existed, but Mao almost overthrew it himself. We had a Deng era, we had a Hu era, and we have a Xi era now. The same thing happened with the Soviet Union — the way the party worked and the way it looked at its relationship with the world changed dramatically over its 75-year history. The one thing I can be sure about is China is going to change a lot over the next 30 years. How, if at all, should the US be thinking about what Chinese governance looks like in a world after Xi?

R. Nicholas Burns: Part of being competitive — and we’re waging a competitive relationship — is to object to much of that system, to object to the denial of basic human rights in Xinjiang and in Hong Kong and Tibet. I’ve gone to church here in multiple cities. We object to the lack of religious freedom in this country. That’s part of what the competition is. It’s normative. It’s about the nature of what governments should and should not do in giving rights or denying rights to their own people.

In saying that, one of the problems with a strategy of winning is, would the Chinese system actually implode? It doesn’t mean we want to preserve the system because we’re competing against major aspects of the system. But you do have to ask the question, what would be the consequence of trying to win, and would that strengthen us in some ways? What would we lose by our inability to work with them and work with others? That’s the central question that’s got to be asked.

Jordan Schneider: If China ever returns to a late ’70s, ’80s ferment, is there anything that the US can and should do to help bring about or prepare for that moment?

R. Nicholas Burns: Jordan, at one point in my career, a long time ago, I was State Department spokesperson for President Clinton, and I learned a big lesson there. Don’t ever answer a hypothetical question. That’s a supremely good but hypothetical question. I’m still the American ambassador to China for another eight days, so maybe ask me six months from now, but not today.

Jordan Schneider: Fair enough. Let’s go back to Kissinger. It’s fair to say that he is one of the most skilled diplomats. He had as many reps as anyone is ever going to get at the stakes that he did. One of the big takeaways I had from your book is two of the things he was most proud of and excited about and thought he did the best job on — Rhodesia and Vietnam — ended up being maybe the two biggest disasters. You could put Bangladesh in another category maybe. What does that mean if the person who is the best you’ll ever get at this and thought he was doing a great job actually had two of the worst outcomes he was ever involved in?

R. Nicholas Burns: Well, in a long career — it’s extraordinary that I’ve just picked up and I’m starting to read the book he wrote, posthumously published, with Eric Schmidt on AI. He was in his 100th and 101st years on earth, writing about AI. Think of the longevity of that career which begins in Nazi Germany and goes through the Second World War and all the way through.

No one’s going to get everything right. He was intrigued by the fact that we wanted to write a chapter in that book about his attempt to begin to abolish white minority rule in Rhodesia and then to get at the bigger question of the apartheid regime in South Africa. He made clear to us, this is 1975-76, that he and President Ford had decided they wanted to separate themselves from the white regimes in then-Rhodesia, later Zimbabwe and South Africa. He didn’t succeed.

What we did in doing some of the research of the book was to talk to many of the American diplomats and other diplomats from around the world with whom he worked. Most of them would say he didn’t succeed as Secretary of State, but he laid the groundwork for the Lancaster House conference in 1978, just a year after he left power, that overthrew white minority rule and established the modern state of Zimbabwe. He was very interested that we were going to study that because he said it had been forgotten as part of his work. He leaned into it and spent a lot of time with us going through his strategic assumptions and what he tried to do tactically.

The other thing, Jordan, that I remember very clearly from our conversations with him — and I also talked to him about this as I was preparing to come out here — is that there’s been a lot of criticism historically of Secretary Kissinger that he didn’t elevate human rights or the nature of the regime he was negotiating with, in this case, the Soviet Union or Mao’s China. He made a point — and I think Niall Ferguson, his biographer, has been making the same point — that he thought the prevention of nuclear war, driving down the probability of nuclear war, and creating some kind of balance in great power relationships was a highly moral objective.

That was an interesting product of all the conversations that we had with him. As we talk about US-China relationships, we’ve taken the position that we cannot afford not to talk about human rights. I just issued a statement a couple of days ago about a young man named Ekpar Asat, who is a Uyghur young man who’s been incarcerated for the last eight years unfairly because he was trying to promote better relations between Han Chinese and Uyghurs. We’ve decided we’ve got to stand up for the massive human rights deficiencies of the People’s Republic of China here. We’ve made a different calculation decades later, but that’s how he responded to the criticism that he was not sufficiently concerned about human rights.

Jordan Schneider: I really like the Rhodesia chapter. You guys made a great illustration of just how much of a tour de force it was from him at the negotiation table to doing the 4D chess of lining Nyerere up and the South Africans up. You convinced me that it helped get Zimbabwe created. But it’s a cruel irony that the creation of Zimbabwe ended up being one of the biggest humanitarian catastrophes of the past 30 years.

R. Nicholas Burns: The idea was that ending white racist regimes was the right thing to do. Obviously, Kissinger didn’t foresee what would happen with Robert Mugabe in the ensuing decades.

Red Lines and Great Power Responsibilities

Jordan Schneider: Regarding Salt Typhoon — should I be more annoyed with the Chinese or with the US cybersecurity establishment for allowing it to happen in the first place?

R. Nicholas Burns: You should be annoyed with the Chinese. One of the points we’ve been making to the Chinese leadership in recent weeks is, you’ve gone way too far. These are objectionable assaults on American infrastructure, on telecommunications and other aspects of our infrastructure, and on the rights of Americans. There’s going to be a price to pay. We’ve already begun to sanction some of the companies and the hacker groups involved in this. It’s become a major issue in this relationship and not just with us — because the Chinese have been going after these extraordinarily aggressive cyber assaults on many American allies in Asia and in Europe.

We have made it clear to the Chinese, as have some of the allies, that this has got to stop. There have to be boundaries here. What I’ve been thinking about as I wrap up my time here is how aggressive the Chinese have been on multiple fronts — on cyber in the South China Sea, these repeated attempts to intimidate the Philippines, our treaty ally, their attempts to intimidate Japanese administrative control of the Senkaku Islands. We’ve been having conversations with the Japanese about this, and we both objected to the Chinese.

Look at what they’ve done recently over the last year on Taiwan, the simulated blockade earlier in the autumn. Then think about this massive undertaking where all these Chinese companies — and the Chinese deny this, but it’s true — are giving very critical support to the Russian defense industrial base and allowing Russia to continue this war in Ukraine. There are other examples, such as what the Chinese are not doing to use their influence with Iran to stop the Houthi rebels in the Red Sea.

On issue after issue, the Chinese are over-the-top assertive against American, Japanese, and European interests. There’s a price to be paid for this.

I’ve tried to tell people here, “You have united both of our political parties in Washington, and both houses of Congress rightfully are pushing back against you because of the number of assaults against really important, in some cases vital, American interests.”

They’ve just got to understand how big a hole they’ve dug for themselves as they prepare to work with another administration.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on Chinese international aggrandizement. There’s one argument that Putin — before he invaded Ukraine — invaded Georgia, invaded a smaller piece of Ukraine, he sort of took over Syria. You have a Xi track record — what happened on the Indian border is not great, what’s happening right now in the South China Sea, also not great. But this is almost a difference in kind between actually rolling tanks into countries. Is that fair? How do you reflect on what Chinese international aggression looks like when you’re thinking about even more scary eventualities like a blockade or invasion of Taiwan?

R. Nicholas Burns: The problem, Jordan, is that they’re challenging the very basis of country sovereignty. They don’t have a leg to stand on in their claims in the Spratlys and Paracels, these exorbitant claims for the islands and islets hundreds of miles beyond the territorial waters of China. They don’t have any support legally for this, but they’ve done it through force of arms to the Philippines and the other claimants in the Spratlys and Paracels.

They have been extraordinarily aggressive against the Japanese. The number of air sorties and naval sorties on a nearly daily basis — you do have this new agreement between India and China, and yet you see India in the Quad. The Indians are one of our strongest partners now in the Indo-Pacific because of this uncertainty about what China is up to on their long Himalayan border.

Until recently, until the Biden administration came into power, you saw a lot of voices in Europe about taking some kind of middle ground between China and the United States. When President Biden came into office in 2021, the EU was on the verge of a major investment treaty between China and the EU.

Look at the hole the Chinese have dug for themselves now. The European governments have risen up against China because China is assaulting the existential issue confronting Europe — the indivisibility of the continent. It’s the fact that there’s war now in one of the major states of Europe, Ukraine, that Putin is assaulting the sovereignty of Ukraine.

Look at all these mysterious incidents happening in the Baltic Sea with cables being cut and the suspicion that the Chinese were involved in that. They have really harmed their relationships with Europe through this uber-aggressive policy, especially the alignment with Russia, with North Korea, and with Iran.

This gets back to the question I asked at the beginning of this interview that’s been on my mind a lot. At some point, the Chinese are going to have to decide, are they really going to be for the next 10 years with these agents of disorder in the world, or do they want to position themselves differently so that they don’t dig a hole for themselves with the European Union, the United States, Japan, the Philippines, Australia, India? If you alienate all those countries, that’s well more than 50-60% of global GDP.

Jordan Schneider: My theory of why China keeps doing this is that they don’t actually see as many costs as they could, and they don’t really think they’re going to trigger World War Three or global 50% tariffs.

How would you assess this? Biden has placed a lot of emphasis on signing new military agreements, and now we have AUKUS and the Quad — but it seems like China is not getting the message yet. Will they ever? Will that be okay as long as they don’t invade Taiwan?

R. Nicholas Burns: Frankly, in their heart of hearts, I sense that the Chinese are really worried that they’ve lost Europe, maybe temporarily for the life of the Ukraine crisis. We’ll have to see how that plays out over the next couple of years, but they’re worried about that. There’s a massive charm offensive underway by the Chinese Foreign Ministry to try to win back some credibility with the Europeans.

The Europeans have been very clear — with the exception of countries like Hungary, an outlier — about the price that China has to pay for supporting Putin in the war in Ukraine. Similarly, out here in the Indo-Pacific you’ve seen a real toughening of the policies of Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines against what they see as Chinese overreach.

One of President Biden’s accomplishments of over the last four years is that the United States is in a stronger strategic position in the Indo-Pacific in this long-running competition with China. In large part, it’s because we’ve strengthened our alliances with those three countries and with Australia, we’ve created AUKUS, and the Quad now is meeting at the head of government level. I just had a Quad meeting yesterday here in Beijing with my Japanese, Australian, and Indian counterparts. We meet regularly and we are lined up together out here in Beijing. That wasn’t the case five or six years ago, but it’s the case now because of Chinese overreach.

There have been penalties here that the Chinese are very well aware of. One of my takeaways, as I conclude my time here in Beijing, is the allies of the United States in the Indo-Pacific are force multipliers for American power. Academically or politically, diplomatically, a lot of people just look at this competition between the U.S. and China and they try to size up the weight — economic, strategic, military — of the two countries and compare. That’s not a valid comparison on the U.S. side, because China has no allies to speak of. To measure strength, you’ve got to put the U.S. alongside Japan, the Philippines, Australia, and, in many ways, India.

For me as a diplomat, the most important thing we can do in this competition is to keep the allies close. I also say that as a former American ambassador to NATO — and I was there on 9/11. Let me name two countries that stood up on 9/11, and called me immediately in the aftermath of the strikes. The Canadian ambassador called me first and said, “Let’s invoke Article 5.” Then the Danish ambassador called me.

I am an alliance-centered American who believes that these allies are just precious strengths for America because they multiply our power. These are reliable countries that have been with us through thick and thin. As I walk away from this job, I’ve been working very closely with all those allied ambassadors here and we are better off for it. I really hope that the United States is going to remain true to those alliances because they’re in our self-interest.

Jordan Schneider: This gets to a question of what is the scarier world state. There are a lot of instances in history — if you look in the Nazi archives, in the Japanese archives, in the Weimar Germany archives — where you see leaders who see they’re hitting an inflection point. Even if they don’t have good chances, they’re only going to get worse. This thinking has started some really awful and tragic wars.

But there are also times where countries have seen the writing on the wall and realized that maybe there’s a different, more peaceful approach to engaging with their neighbors. What do you think about what shifting global power balances mean for China’s leadership today and maybe tomorrow? What could the U.S. and the rest of the world do to help push the thinking one way versus the other?

R. Nicholas Burns: It’s a very thoughtful question, Jordan. You need an academic seminar on this or we could design a whole course at a university around it. Obviously, the United States needs to keep the allies close. They’re critical for the United States in the 21st century. We are still the single most powerful country without any question across all the dimensions of national power. We want that to continue. We don’t want China to be that country. You want the United States to be that country.

What’s unusual about this century, what’s changed in this century is that you can’t stand alone. Isolationism won’t work in a world that has so many different power vectors and challenges that are transnational in nature. We’ve got to have these allies. That’s point one.

Point two, obviously, the United States needs to strengthen its game in our strategy in the global South. I was in Lima with President Biden. I stayed an extra day and spent some time with Peruvians who are very smart about China, by the way, and they’re very involved with China. It’s painful to reflect upon the fact that 20 years ago the United States was the leading trade partner of nearly every country in South America. Now China is the leading trade partner most South American countries.

We need to have a concerted, bipartisan long-term national strategy to be more engaged economically, politically, and diplomatically in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and Central Asia. There’s a real battle for that kind of power influence in the ASEAN countries here in Asia.

We also have to stay engaged as a society with China. One of the peculiar aspects of what happened here because of COVID and the Chinese policy of zero COVID, which made it impossible to come here in my first year or two, is that we’ve only had one American governor visit China in the last five years. It was Governor Gavin Newsom, who came here in October 2023. We’ve only had one congressional delegation over five years. It was an extraordinarily effective delegation because it was bipartisan. The majority leader, Chuck Schumer came out with Senator Mike Crapo of Idaho and four other members of Congress, three Republicans and three Democrats. They were very effective in their meeting with President Xi Jinping on fentanyl. They actually arrived the day of the Hamas attack against Israel, October 7, 2023.

My message when I become a private citizen and meet with members of Congress will be, we need members of Congress to come here. We need China hawks — and I consider myself in many ways a China hawk, by the way — to be here to size up the adversary and to see this country up close. It’s not a nice thing to do. You do it because you need to understand the adversary better in the adversary’s home, on the adversary’s home turf.

Those are some practical things that I think we should try to do on a bipartisan basis because we want to preserve a bipartisan, rough consensus on how to deal with the Chinese. Those are a couple of ideas on how we can strengthen our game.

Jordan Schneider: On how to get China to understand — if things go well in the next 10 years, you have an increasing global national power balance where the U.S. and allies are gaining on China and friends. What can the U.S. do to communicate that to China in a way where they don’t do what Imperial Japan did in 1941?

R. Nicholas Burns: The Chinese are already looking — I read the Chinese press every day with my staff — and trying to make the point as they look ahead to the next couple of months that the United States is an unreliable ally, that the United States is becoming increasingly insular and isolationist and China is not. This is just Chinese propaganda — that the Chinese play by the rules, that they’re invested in the international system, that they’re responsible, that you can count on us.

If we walk away from the Paris Climate Change Agreement, the Chinese are saying if the Americans walk away, they’re going to be irresponsible, but we Chinese will not walk away. We should not want to give the Chinese those successes. Remaining engaged in the international system, if you want to be effective in the global south, you have to be present in arenas that are important to the Global South. That gets to climate change, it gets to trade, it gets to long-term infrastructure lending that won’t bankrupt and lead to massive indebtedness on the part of these countries.

The Biden administration has begun to make real changes there. We just need to have that continued. I hope in the future Congress can play a big role, which is another reason why I really hope we can get senators and members of the House out here, take a look at this competition and figure out from the ground here how we can be more effective. Keeping allies with us is going to be absolutely critical. Being respectful of our NATO allies, being respectful of their basic sovereignty and borders — I never thought we’d have to say that — is very important.

Jordan Schneider: Well, China just is trying to take islands, but at least Trump is offering to buy them. Do you think that’s a meaningful difference?

R. Nicholas Burns: Jordan, can I say this? That’s a really important point you just made. We have had the strategic advantage. We’re winning the argument globally against Russia on whether or not Russia had the right to invade Ukraine — it didn’t. We are winning the argument globally that China does not have the right to use force across the Taiwan Strait, that it ought to commit, it must commit to a peaceful resolution. But if you don’t act like that yourself, if you contest other countries’ sovereignty and borders, allied countries, it gives a pass to Putin and Xi Jinping that we shouldn’t want to give them.

Jordan Schneider: Would you like to offer any advice for the incoming administration and your successor?

R. Nicholas Burns: What I’ve actually tried not to do is to give a lot of specific advice. I’ve been asked a ton of times to comment on this or that statement or what’s the new administration going to do. I’ve declined because obviously they have a right to figure out what they want to do, get their team together. I don’t want to complicate things, but we just talked about matters of high policy about how the United States should act in the world. I gave you my honest answer.

I’ll say this about the new administration: I don’t know Senator David Perdue, but when he was nominated by President-elect Trump, I said publicly that I congratulated him, wished him well, and that I would give him as much help as I can. I’ve reached out to him and I hope to meet him before he goes out to China. I really want him to succeed because if he succeeds, the country succeeds.

We have a huge mission out here. We have one of the largest American embassies in the world in Beijing and our four consulates in Shenyang, Wuhan, Shanghai, and Guangzhou — 48 U.S. government agencies. I think he’s very well qualified, based on his career and what he did in the United States Senate, to be the American ambassador. We out here are nonpartisan as civil service. We were nonpartisan throughout the election. It didn’t come into the lifeblood of this embassy at all. I was really proud of our team.

As I’ve thought about it and explained to people out here, we have enough problems dealing with the government of the People’s Republic of China. We want to stay out of the divides back home. That’s why I thought it was really important for me to say I’m going to give Ambassador Perdue, when he does become ambassador, all the help I can.

Jordan Schneider: Kissinger pioneered many things. One among them was Kissinger Associates. The path where former officials end up serving government relations jobs for countries and companies — has that been like a net positive or more neutral or negative development over the past 50 years, that this is something a lot of former officials end up doing?

R. Nicholas Burns: I think it depends on what the nature of the activity is. I retired actually the first time from the Foreign Service in 2008, and I was a professor at Harvard. But I also consulted for a D.C. consulting firm and I found it really interesting and enriching. People have to make their own choices as to what they do out of government.

Jordan Schneider: What are your biggest outstanding analytical questions about China?

R. Nicholas Burns: The biggest question is how China wants to lead as a global power. Let me give you two examples. Who do they want to work with most prominently? Can they work more effectively with Japan, the United States, Western Europe, the EU, and NATO? They’ve got real problems working with all of us now.

The door is open. We would like to see China be a more responsible country on these big international questions than it has been. The door is open to that kind of cooperation if they’re willing to walk through it, but they have not been willing because they’ve got this intense association with Russia. Russia is a country that’s assaulting the whole edifice of the global system that we built after the Second World War.

I’m afraid that China, through its Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative and Global Civilization Initiative, is giving us the impression that it wants to alter the global system and make it more friendly for authoritarian countries. That’s a big question that the Chinese leadership is going to have to reflect upon. Do they really want to stay with North Korea, Iran, and Russia in a loose association? Is that going to be good for Chinese interests?

The second question we’ve been reflecting on is that great powers have responsibilities to do really difficult things — to negotiate a ceasefire in Lebanon, as the United States succeeded in doing, to negotiate a ceasefire in Gaza. We’re not there yet, but we’ve got to have a ceasefire in Gaza and the hostages released. You expend a lot of capital when you do that. You can make yourself very unpopular, but there’s a greater good.

We’ve not seen that kind of attitude from the Chinese. They have an opportunity in the Red Sea because China is the major importer of Iranian oil and they have a very strong strategic relationship with the Iranian leadership. If any country could convince Iran to use its influence with the Houthi rebels, it’s China. They haven’t done it. We have said, and I’ve certainly said to them in repeated meetings, you really ought to use your influence here. The world needs you to do it so the commercial shipping traffic can resume along one of the major routes of the international system.

They’ve been on the sidelines of the crisis in Gaza. They talk every day about the Palestinians, but what have they really done to help the Palestinians? When you get to be a global power — and China is a global power by virtue of its economic and military strength, technological strength — you gotta act like it. We haven’t seen that from the Chinese.

Jordan Schneider: What open question about U.S.-China relations are you curious about going forward? On what topic do you wish you could read a book that hasn’t yet been written?

R. Nicholas Burns: I believe that China is our strongest adversary now (competitor, adversary, you can choose the word) and they will be 10 years from now, maybe 20 years from now. We have got to be stronger as a country to take on that competition with China.

I worry that we don’t have enough American students here learning Mandarin in the current generation of 20-year-olds. For now, we have a core group of people in the country who understand China, speak Mandarin, and have had experience here. One of my great advantages as ambassador is that this building that I’m in, our embassy, is filled with people on their second, third, fourth China tour. They speak Mandarin, they understand this country. I worry that my successor 10 years from now, 15 years from now will not have that deep bench.

We have to think about this competition carefully. There’s the hawk in me in the sense we’ve got to compete and we can’t afford to become the second strongest power out here in the Indo-Pacific ten years from now. We’ve got to compete and succeed in the competition, but at the same time, we have to engage the Chinese.

It’s not 50-50 — it’s 80% competition, 20% engagement. The engagement part is important because it’s about other national interests that we have. Fentanyl, climate change, and getting American prisoners out of jail — we’ve helped four Americans get out of jail in the last several months because of quiet diplomacy with the Chinese.

If we don’t see both sides of that equation, then we don’t serve American national interests. Because the ultimate goal here is to compete, but also to live with China in the world, avoid war, and drive down the probability of conflict. That doesn’t always come out in the American debate. There’s so much focus on competition. The harder and more complicated question is, how do you do both at once with competition being the overwhelming priority?

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned the generational change in national security leadership. We had this situation where by the time we’re starting wars in the Middle East, all we have are Soviet analysts running the game. Ten, twenty years from now, we’ll probably have ambassadors to China and secretaries of state who speak Mandarin. I’m curious, reflecting about what having the principals also be regional specialists in the place that’s most impactful in the world, or where the U.S. is most focused — what that does and doesn’t change about how policy gets formulated, implemented?

R. Nicholas Burns: My career has been in the American Foreign Service, and I’m so proud of the Foreign Service. I’m actually a big proponent of not being a generalist. Here’s where I disagree, respectfully, with Secretary Kissinger — he didn’t want to have lots of people specializing on Latin America or the Soviet Union or China. He wanted people to have general skills and to have diverse careers.

We need people like that. I was such a person. I served in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and on Soviet affairs from the White House. I was a generalist. But we need China specialists. I’ve started a program here in our embassy called “Path to Senior Leadership.” We read books together on the U.S.-China relationship. We think through careers — how do you build a career where you become an expert on the history, culture, politics, economics, language of China? I want our younger officers here in China to think about coming back two or three times, and I encourage them to do that.

We also need to have Arabists, obviously, and Latin Americanists. When I worked for Secretary Rice — and I have huge respect for her — we concluded that we needed about half of our officers to be specialists and half to be generalists. That’s probably about right.

A lot of signals are sent to our Foreign Service officers about careers — “Don’t focus on one country, don’t focus on one language, you’re going to get promoted more easily if you do two or three regions.” I don’t always trust that or agree with it. I’ve had a lot of conversations with our great younger diplomats here about becoming the George Kennan of your generation, or the Victoria Nuland or John Beyrle (probably the two great Russia specialists of my generation in the Foreign Service). You’re going to serve the national interest. You’re going to have a fulfilling career.

The Pentagon and the Treasury Department, we all need to think about how we bring along the next generation. I didn’t expect when I came out here as ambassador that I’d spend as much time as I have, but I’m glad I did, trying to work with our younger officers to think through and help train them for the longer-term goal of having profoundly important China specialists in the U.S. government.

We hear a lot of criticism of the federal government, and it’s not perfect, but I’ve served in it a long time and now I’ve come back into it for these past three years. We have tremendously talented people in the Foreign Service, in the Commercial Service, at the Commerce Department, in the Treasury Department, in DoD — and they are a national asset. We’ve got to keep those people in government, encourage them, and thank them more often than we do for their service.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about Martin Luther King Jr. and theories of change. You have the NAACP approach, which involves technocratic methods — filing lawsuits and building brick by brick. Then you had Dr. King saying that as long as you’re pure and spread truth, people will come around whether they like it or not — even if it doesn’t feel popular or tactical and even if JFK is saying you should wait two weeks.

Do you have any reflections on the tension between the prophetic and the technocratic when it comes to international relations?

R. Nicholas Burns: Thank you for bringing up Dr. King. He was somebody I really admired when I was a teenager. I was in sixth grade when he was assassinated, in April 1968. Our sixth grade teacher wheeled a television set into our classroom and said, “We’re going to watch the funeral of a great man.” That awakened me as a 12-year-old to what a heroic figure he is in American history.

Your question about politics and foreign policy — what kind of pace of change should we seek or the degree of change we seek? It depends on the moment, the era, the country, whether that change can be brought about easily or with difficulty. The United States has played the most important role in the world since the end of the war 80 years ago. We’re commemorating that here in China. We’re working to commemorate the end of the war because we were allied with China back then.

A lot of the battle for the future is going to be within the United States itself in terms of what we tell each other about our responsibilities as a great power to the rest of the world and to our own country. As a career diplomat, I deeply believe the United States has to be outward focused, true to its allies, maintain those alliances, see the allies as force multipliers, as adding to American power. They also add to the normative struggle that we have with communism — communism in China, communism as pseudo-communism or authoritarianism as practiced by Vladimir Putin. We differ with them and we object to the fact that they deny individual liberties and individual freedom, and we support that.

We can’t win these battles if we stay at home and forsake our alliances and don’t think strategically about American power overseas. Part of what’s going to happen in the next 10 or 20 years will depend on our own national conversation about these issues.

Jordan Schneider: I’m coming off paternity leave, and as a new father I’ve been reading a lot of Civil War history.

R. Nicholas Burns: Congratulations! I’m reading Jon Meacham’s book on Lincoln, And There Was Light. It’s a great book about Lincoln’s lifelong focus on the issue of slavery starting from the time he was a little kid, and it’s really been enlightening for me. It’s not a complete biography — it’s really about the question of race and slavery leading up to the Emancipation Proclamation.

Jordan Schneider: Lincoln famously, a month before releasing the Emancipation Proclamation, wrote a letter stating that if he were to free the slaves, it would only be because it was necessary to save the Union. A lot of historians over the past 150 years have given him a really hard time for that.

Some argue that what Lincoln was doing was making it easier for the Democrats in the North and the Copperheads of the world to stomach what he was about to do with the Emancipation Proclamation.

Relating that to today — that’s a very un-MLK-like thing to do, to disavow the thing that you most believe in, that you’re standing on from the strongest moral perspective. Thoughts on that? That’s a really interesting contrast. I’m curious how that relates to idealism and how America should walk in the world.

R. Nicholas Burns: I am neither a Civil War historian nor an expert on Lincoln, but consult Jon Meacham. Meacham says Lincoln had to deal with the Copperheads, the anti-war Democrats in the Northern states. He had to deal with the border states and keep everything together and defeat the Confederacy. What I get from Meacham is that Lincoln had to do that and bring people along slowly. His views also evolved towards the very end of his life, holding a radically different view. But that’s just based on my reading.

Jordan Schneider: This brings us back to the Kissinger question — what types of things should the U.S. be willing to hold its nose at for the sake of advancing a greater good? Where do you draw the line?

R. Nicholas Burns: I’ve really enjoyed this conversation and I enjoyed my time as a professor when we could have lots of conversations about this. We can have another conversation when I’m a private citizen.

But in that context, here’s how I would answer your question. I’ve lived in eight countries in the last 52 years, started when I was 17, living overseas and in Africa, in the Middle East, in Europe and in Asia, places where I’ve lived and other places where I’ve traveled.

What stands out in the minds of foreigners about the United States is we believe in human freedom. That’s how people see us. While we are not a perfect democracy, we are a democracy and we have a balance of power, and our constitutional freedoms and the Bill of Rights are the backbone of this country.

The second thing people really appreciate about the United States is that, however imperfect we have been in getting some things wrong, like the Iraq War back 20 years ago, we are devoted to being a responsible global power and we’re a good ally. When other countries get in trouble, we back them up. As I saw on 9/11 when I was ambassador to NATO, when we get in trouble, our best allies back us up, like Denmark and Canada.

We’ve got to protect those two strengths that we have in the world. It’s our moral strength that comes out of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and the way we’ve acted inside our country, and it’s the way we’ve acted responsibly, particularly since the end of the Second World War, in the great generation of Truman and Eisenhower and Kennan that led us to be permanently engaged because that was the American national interest.

If you look at our national conversation, some of that is up for grabs right now and is being questioned. I tend to be a defender of the faith. Stay with what made America great. That was both of those things: our democracy at home and our reliability as an ally and partner of like-minded democratic countries in the Indo-Pacific and Europe and elsewhere in the world. There’s a lot at stake here for us to get these two right. I know what side I’m on on both of these questions.

I used to think that the enormous loss of 20 million jobs to China, creating a 200 million middle class of Chinese, would avoid a World War III

I think I was wrong.

Fuck China

Fundamental misunderstanding by Ambassador Burns in believing that the PRC has simply “fallen in with the wrong crowd” by associating with these disruptive actors like Russia and North Korea who are trying to undermine the western-led world order. The U.S. strategy of trying to convince PRC leadership of the value of becoming “more responsible” has not worked for decades, it won’t work today. It’s actually condescending to think PRC leaders don’t know what they’re doing. As Xi said to Putin at the Kremlin, you and I are driving these changes unseen in 100 years, and let’s keep it up.