Anthropic's Dario Amodei on AI Competition

DeepSeek, export controls, the future of democracy

Dario Amodei is the CEO of Anthropic. In today’s interview, we discuss…

Whether an AI innovation race is inevitable between the US and China,

How the US should update export controls in light of DeepSeek’s R1 release,

DeepSeek’s willingness to generate information about bioweapons,

His message to Chinese engineers and DeepSeek itself,

Technical defenses against model distillation and AI espionage,

How advanced AI could eventually impact democracy,

The tension between export controls and believing that AI will broadly increase human flourishing.

Have a listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

Export Controls and AI Benevolence

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with a brief picture of how rapid AI progress could cash out in terms of national power.

Dario Amodei: A few months ago, I wrote an essay called “Machines of Loving Grace,” where I focused on many of the positive applications of very powerful AI. I had this definition of what I think very powerful AI will look like. I use this phrase, “country of geniuses in a datacenter,” to describe what all the companies are trying to build. The phrase is very evocative for understanding the implications.

It’s as if you drop down a country of 10 million people, except all of them are polymathic Nobel Prize winners in any field. What does that do to national power? Presumably, that does a lot of things to national power. It greatly accelerates economic ability. It greatly accelerates science. Perhaps, unfortunately, it probably also has implications for intelligence and national defense — both in terms of controlling swarms of drones or analyzing intelligence information. Generally having a lot of incredibly smart entities who can control anything in a virtual way — that’s going to be a source of a lot of power in many different ways.

Jordan Schneider: Why write an essay about export controls?

Dario Amodei: Seeing the reaction to DeepSeek and being in the industry, being one of the people who’s developing the technology, I saw a lot of things that were just not correct. They came from people who weren’t following closely the actual arc of the technology but were now paying attention because there was this novel fact that it was a model developed by a Chinese company. They had missed many of the previous steps and misunderstood the dynamics of the field. They said, “Oh my God, this is really cheap,” and maybe they had a stereotype of cheap things being made in China and pattern-matched to that stereotype.

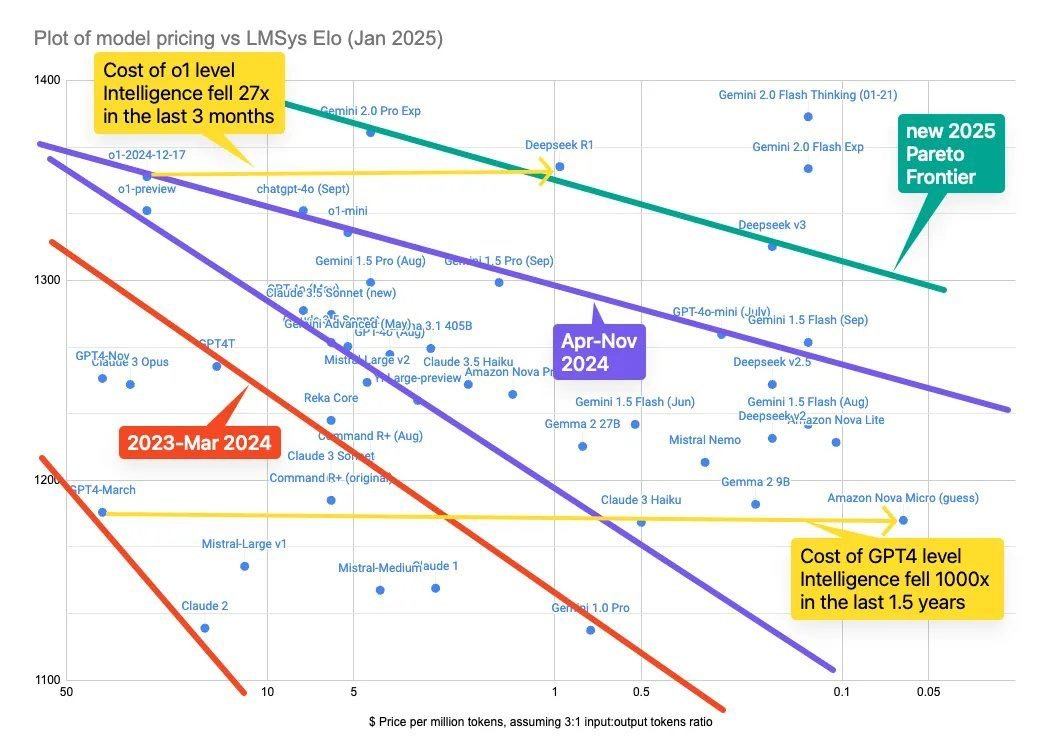

The reality, as I said in the essay, is that there’s been an ongoing trend of cost decreases in this field at the same time as we’ve spent more and more money to train the models. They’re so powerful and so economically useful that the countervailing trend of just spending more to make a better and smarter thing has outstripped the trend of making things cheaper.

The timing has been such that DeepSeek was able to release something that genuinely had some important innovations in it but was along the same cost-decrease curve that we’ve seen for AI in the past. This wasn’t making something for 6 million that cost the other companies billions. This was more like we’ve seen a 4x cost decrease per year — roughly that, give or take, relative to models that had been trained half a year to a year ago.

We’ll see that models of that quality will be now produced very cheaply by multiple players, while multiple players, including probably DeepSeek, will spend much more money to train much more powerful models. The new fact here is that there’s a new competitor. In the big companies that can train AI — Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, perhaps Meta and xAI — now DeepSeek is maybe being added to that category. Maybe we’ll have other companies in China that do that as well. That is a milestone. That is something that didn’t happen before. It is a matter of concern to me, but people were way overreacting and misunderstanding the implications.

“I think [DeepSeek’s releases] make export control policies even more existentially important than they were a week ago.”

~ Dario Amodei, “On DeepSeek and Export Controls”

Jordan Schneider: Your big update is on the skill of one Chinese player and perhaps more Chinese players. What, if anything, should people reassess specifically on the model side about what you can expect going forward about the gap?

Dario Amodei: I want to be clear — we’ve been tracking DeepSeek for a long time. We’ve been aware of DeepSeek as the likely most capable player in China for over a year. That’s informed our view of how things are going to evolve. For those who are just seeing DeepSeek, the update is, there were three to five companies in the US who could make frontier or near-frontier models. Now there are three to five companies in the US and one company in China. Whether they continue to make near-frontier models depends upon how many chips they can get access to and whether they can get access to chips at a much larger scale than those they’ve been able to get access to now.

Jordan Schneider: The AI safety community, yourself included, warned for years about the risks of racing dynamics. I’m curious if you could talk me through how you got to your current view on export controls.

Dario Amodei: The two things aren’t really opposed. I’m still concerned about the idea of a race in particular. My worry is that if the US and China are equally matched in terms of this technology, neck and neck at every stage, then there will be basically nothing preventing both sides. It will completely rationally make sense for both sides to keep pushing the technology forward as it has so much economic value, so much military value.

Absent very strong evidence of danger, there’s going to be a fair amount of incentive to continue developing it. In particular, a worry I have is about legislation in the United States. Like efforts to measure and perhaps at some point even restrict the risks of AI systems — the dangers, the misuse of them by individuals, for example, for bio attacks, or the autonomous dangers of the systems themselves. There have been various legislation in the US over the last year or so. One argument that’s been given against the legislation is, “Hey, if we slow ourselves down, China will just jump ahead and beat us.” That argument is absolutely correct.

The only way that I see that we can kind of do both — we have to make sure that we’re ahead of China and other authoritarian countries both because I don’t think they would use powerful AI very well and because if we’re not ahead, there’s this racing dynamic — yet somehow we have to also protect against the dangers of AI systems we ourselves build. My guess is the best way to do this, and it may be futile, it may not work out, but my guess is that the best way to do this is with something like export controls. We can create a margin between us and China.

Let’s say we’re two years ahead. Maybe we can spend six months of those two years to ensure that the things we build ourselves are safe. In other words, we’re still ahead and we’re able to make things safe. If things are evenly matched, then we have to worry that what they build isn’t safe, and at the same time we have to worry about them dominating us with the technology. That puts us in a very bad dilemma where there are no options.

For a long time — this is not anything new, this is just the first time I’m talking about it — I’ve felt that keeping the US ahead of China is very important. It’s in tension with this idea of wanting to be careful in how we develop the technology. But the great thing about export controls is that it almost pushes the federal frontier outward because there are two ways you can stay ahead: you can accelerate a lot, or you can try to hold back your adversary.

I think we’re going to need to do some amount of acceleration, but it’s a move that has trade-offs because the more of that you do, the less time you have to be careful. But I think one way to get around the trade-off to some extent is to impose these export controls because they widen the gap and give us a larger buffer that we can use to govern the technology ourselves. It’s tough though. It’s a tough situation. It’s hard to have both. There are real trade-offs.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on this for one more second. Can you tease out getting to a race-to-the-top logic with China and getting to a race-to-the-top logic with peers in the West?

Dario Amodei: The nice thing about the other companies in the West is that there’s a coordination mechanism between them. They can all be brought under the same law. If someone passes a law, we have to follow it. OpenAI, Meta, Google, and xAI all have to follow it. You can know that you’re engaging in necessary safety practices and others will engage in them as well.

If you do something voluntarily to set an example, as Anthropic has often done, the threat of someone coming in and imposing legislation, even if there isn’t any, is often very valuable in getting other actors to behave well. Because if it looks like one actor is much more responsible and other players are behaving irresponsibly, that really creates incentives for regulators to go after the other players.

But I don’t think that’s possible between the US and China. We’re kind of in a Hobbesian international anarchy. I do think there are opportunities to try to cooperate with China. I’m relatively skeptical of them, but I think we should try. There’s not zero that can be accomplished. In particular, a thing that might change the game is if there was some kind of truly convincing demonstration that AI systems were imminently dangerous, like at the level of human civilization.

I don’t think we have that now. Some safety people think that they have arguments that are super convincing. They have arguments that are suggestive enough to make me worry and take it seriously and factor it into my calculus and do research on it. But certainly, on the merits, the quality of the arguments is not anywhere near strong enough to make two competing superpowers say, “Okay, we’re going to relinquish the technology or we’re going to pause for a certain amount of time to build it really carefully.”

As models become more powerful, I think we’ll understand the extent to which they really are a danger. There’s real uncertainty here. We’re going to learn a lot over the next year, year and a half. If we do find truly compelling evidence that these models are really, truly dangerous in a grand sense, maybe that could change things.

But so far, I’m aware of efforts by the US Government to send a delegation to talk to China about topics related to AI safety. My understanding, again, I obviously wasn’t part of those delegations, is that there wasn’t that much interest from the Chinese side. I hope that changes. I hope there is more interest.

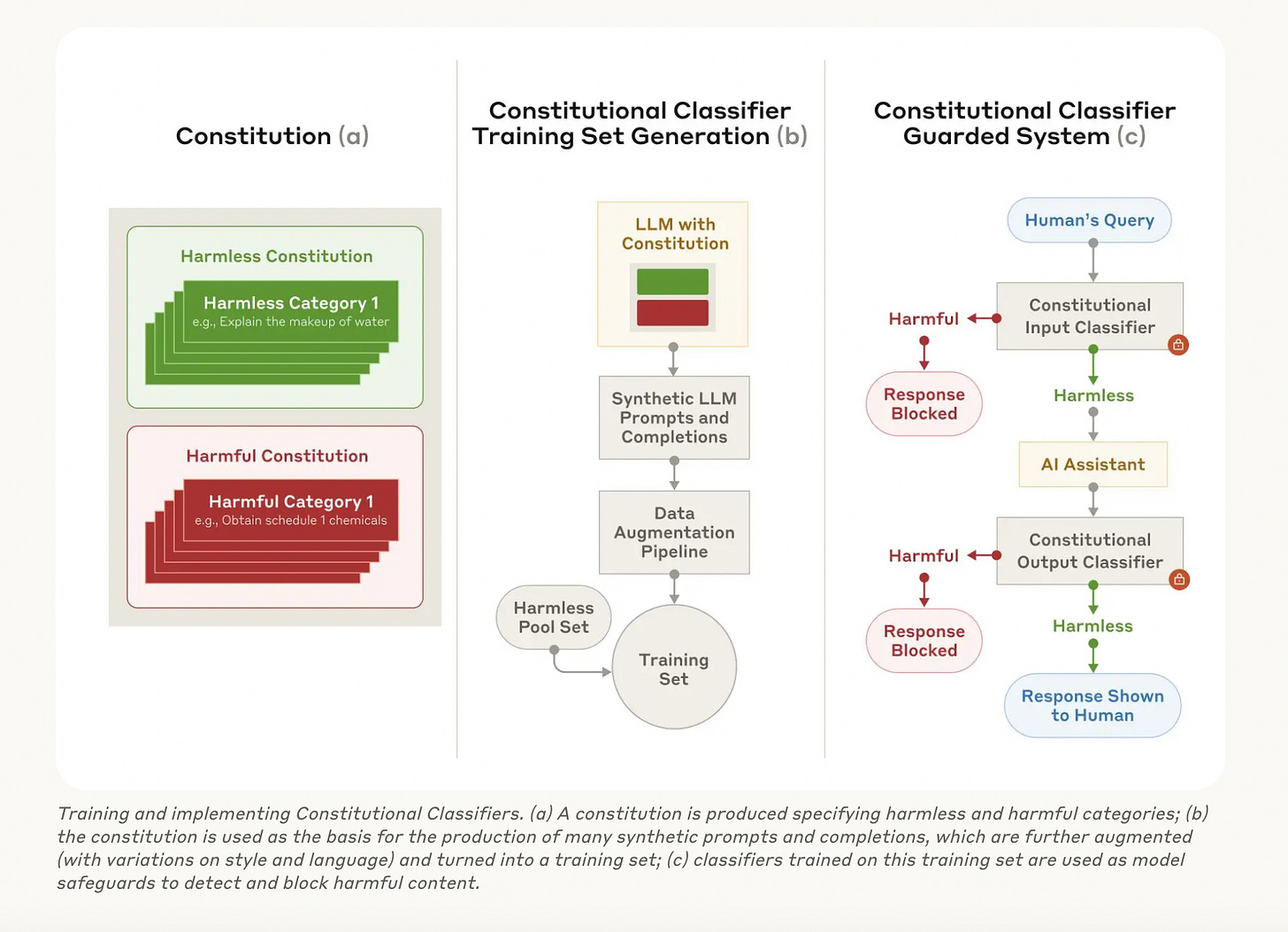

We do lots of stuff in trying to educate the world about AI safety in order to make progress on doing a better job of steering AI systems. We do all this work in interpretability and things like constitutional AI and developing ways to scalably supervise AI systems. We can only hope that these ideas diffuse everywhere, including to China. Just to say it, I’d be happy to have DeepSeek copy these methods — I hope they do. There are ways of making AI systems more reliable.

We should be realistic about the actual situation. We should have a realist view of how international relations work, which is that it’s possible to make progress at the margin, and if some really compelling evidence were available, then maybe it could change things. But look, you have two nation-states that have very different systems of government that have been adversarial for a long time. They’re going to compete over this technology and they’re going to race to build it as fast as they can. That’s what’s going to happen by default.

Jordan Schneider: The only happy, analogous story I can find is Xi deciding to care about climate change. But the thing about climate technology is it’s not super dual-use. There’s economic upside, but not military upside to making a lot of solar panels and electric vehicles.

Dario Amodei: My understanding is China hasn’t always kept its commitments here. There’s been some mix of yes and no. That’s kind of what I would expect here. It’s even a little bit what we see between companies — there’s no law forcing people to adopt RSPs. Companies have voluntarily adopted them.

I think there are differences in the extent to which companies comply with them. Something I could imagine being realistic is yes, there are treaties or kind of aspiring goals signed here and maybe things get 10% safer because of them and we should absolutely seize that 10%. But it’s going to be hard. Again, I would point to, if you really wanted to try to drive cooperation here, you just need really strong evidence that something is a threat to the United States, China and every other country in the world. You need really compelling evidence. What I would say to safety folks who want us to pause, who want us to stop developing the technology: Your number one task should be to develop that evidence.

Jordan Schneider: What chips should and shouldn’t America be selling to China?

Dario Amodei: First, the export controls were never really designed to prevent DeepSeek or any other Chinese company from getting the number of chips that they had at the level of a couple tens of thousands. We should reasonably expect smuggling to happen. DeepSeek probably had a mix of different kinds of chips for about 50,000. Export controls can be more successful at preventing larger acquisitions — they can’t have like a million chips because that’s easily in the tens of billions in economic activity, approaching 100 billion.

Regarding specific chips, there were three chips that they were reported to have. I’m going by Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis. None of this is confirmed — DeepSeek hasn’t stated it themselves. Generally, SemiAnalysis, when it relates to semiconductors, is pretty well sourced.

The claim is they had a mix of H100s, which are the standard chip that we have in the US — something like 10,000 of those. Those must have been smuggled in some form or maybe were proxied through some country other than China where they’re allowed but were used by a Chinese shell company.

The H800 is interesting. It was developed after the first rounds of export controls in 2022. Those export controls put a limit on the combination of the computing power of a chip and the communication bandwidth between chips. The H800 was made to reduce the communication bandwidth between chips to get around the export control. A bunch of H800s were sent to China, and then that loophole was closed in 2023. We actually noticed quite early that there are ways to train your model that get around the lower communication bandwidth. In 2023, a set of export controls were designed that were more robust to being evaded in this way. Presumably, those H800s were shipped between the time of the 2022 ban and the 2023 ban.

The H20 is a chip that is not suitable for training. It therefore must not have been used to make the Base V3 model, which was the first stage that I talked about in my blog post. In the second stage, the R1 model, which was stacked on top of the first and blew up on social media, involves a mix of training and what’s called inference. The H20 chip has not been banned and is good for inference, but not for training. It is possible that the H20 played an augmentative role — that it was used for part of the second stage, even though it could not have been used for the first stage.

Given that inference is increasingly involved in new models, it’s associated with this new paradigm of reasoning models that’s been developed. I would recommend also banning the H20 and attending to making these bans as broad as possible. We always want to be careful — we don’t want to ban other economic activity. For example, there’s no reason to ban sending gaming consoles to China. That would be too much of an economic imposition for something that’s aiming to be targeted. These things have to be designed carefully, but we should ban the H20.

Jordan Schneider: The argument Nvidia makes is the fewer chips we sell into China, the more demand there is for Huawei and the more customers they’ll have. There’s always an announcement that DeepSeek is running super efficiently on Huawei 910Bs or what have you. Thoughts on Chinese domestic capacity to produce chips and what implications are there for the semiconductor manufacturing equipment side of the export controls?

Dario Amodei: Over the timescale of 10 to 15 years, that’s probably correct — they probably will catch up. But the supply chain is really deep there, and as you mentioned, we’ve also export controlled semiconductor manufacturing equipment and repairs on that equipment. It’s actually going to be difficult to make chips that are competitive with say the new Nvidia B100 or with the chips we’re using like Trainium and TPU. The software ecosystem is also not up to snuff — that’s a less important constraint than the hardware.

My sense is that it is unlikely that the Huawei chips become anywhere near comparable to US chips anytime soon. As I wrote in “Machines of Loving Grace” and in the post on export controls, the critical period here where there’s really going to be contention, or where it’s important to achieve a balance of power, is going to happen in 2026, 2027, or at the latest, 2030. Policy should target that time range. Things are moving very fast in the AI world — 10 to 15 years is like an eternity. It’s forever. It’s almost irrelevant.

Jordan Schneider: The Biden administration’s policy was basically to let Chinese firms use chips on Western hyperscalers outside of the PRC. Is that kosher in your book?

Dario Amodei: Near the end they put in place the diffusion rule, which prevents that when it’s Chinese cutout companies. You may be referring to something different.

Jordan Schneider: Like ByteDance being Oracle’s largest customer.

Dario Amodei: The diffusion rule prevents or limits that within tier two countries outside the U.S. Some of it is done in the U.S. as well. It’s of less immediate concern to me because it’s farther up in the supply chain. You can yank the access to the chips instantaneously when they’re doing that. Once the model is trained, of course you have that model. The issue with the chips is once you have the chips, once you have enough of them, you can make model after model. It’s even more so with the semiconductor manufacturing equipment and the fabrication facilities. I’m less immediately concerned about it. Before we get to the end of this, it’s something that needs to be stopped or at least stopped at scale.

Jordan Schneider: What do you make of DeepSeek releasing its model as open source?

Dario Amodei: There were several different properties of the DeepSeek release. One was that the weights of the model were released. Another was that the model was an efficient and strong model on the cost reduction curve, but it’s the first time the point on the cost reduction curve was made by a Chinese company.

The second of those is much more important than the first. Most of what I said in the post on export controls would have been almost entirely the same, maybe entirely the same, if it had just been a model that they were serving via API. Most of the implications just come from the fact that this is a strong model — this is the first time that a Chinese company has produced a strong model. That model will scale up to a very large scale. Whether Chinese companies are able to scale up to millions of chips will be determined by the export control.

On the commercial side, we’ve found that our main competitors are people who release strong models, whether they’re open weights or not. How strong a model is accounts for about 80 to 90% of how much it has mattered in competing against the model. Open weights is different for models than open source — there isn’t source code, there’s just a bunch of numbers. Some of the advantages and differences that are present there are just not present here as much. The analogy breaks down.

Companies that have a history of starting with open weights, at some point they need to monetize, at some point they need to make profit. They often stop doing this. The more important factor here is that a Chinese company is producing a powerful model. Just looking in the marketplace, we haven’t seen any evidence that people prefer models because they’re open weights separately from the behavior of the model. Sometimes you see it, there’s a little bit of a convenience factor.

I said this as early as my Senate testimony in 2023 — open weights models are fine up to some certain scale. They’re not substantively different from closed-weight models.

Jordan Schneider: But you take a margin on every API call, right?

Dario Amodei: The interesting thing is, any kind of model, no matter where it is, has to be served on a cloud. That ends up getting associated with a margin. You have this present either way. At the same time, there are vast differences in the efficiency of inference and there are vast differences in the training of models. The training of models is moving very quickly.

This is actually a relatively small factor. There are weeks when we implement like a 20% improvement in inference efficiency or something like that. The companies are all competing with each other to have the most efficient inference. Most of this is swamped by who has the most efficient inference, who’s training the best model. If a company in China is very good at serving their model for low cost, then that’s an area where competition will happen. Whether the weights are available or not is mostly — not entirely, but mostly — a red herring.

Jordan Schneider: Somewhat related, when do you think governments are going to start getting queasy about models getting open-sourced?

Dario Amodei: From a business perspective, the difference between open and closed is a little bit overblown. From a security perspective, the difference between open and closed models is, for some intents and purposes, overblown. The most important thing is how powerful a model is. If a model is very powerful, then I don’t want it given to the Chinese by being stolen. I also don’t want it given to the Chinese by being released. If a model is not that powerful, then it’s not concerning either way.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of being stolen, anything you want to say about model distillation?

Dario Amodei: There are these reports that, as I said in the blog post, I don’t really comment on one way or another, that DeepSeek distilled model from what might have been OpenAI. They claim they have evidence. I actually haven’t looked closely at it and can’t tell you whether it’s accurate or not. Distillation is certainly something you can do with a model, so it’s possible this is something that has occurred. It’s of course against terms of service.

There are a couple of points that are important. One is developing ways to detect model distillation. It’s probably possible to look at a model and looking at another model which is purportedly distilled from it, to look at the two together and say whether this model has been distilled from that. I’ll generate a bunch of output from one and generate a bunch of output from the other and try to figure out whether one model has been distilled from the other. You can already kind of see when one model has been distilled from another — they have similar mannerisms, they talk in similar ways. There are lots of behavioral signatures. It’d be great to turn this into some kind of measurable statistical test. Then there are monitoring techniques to prevent distillation.

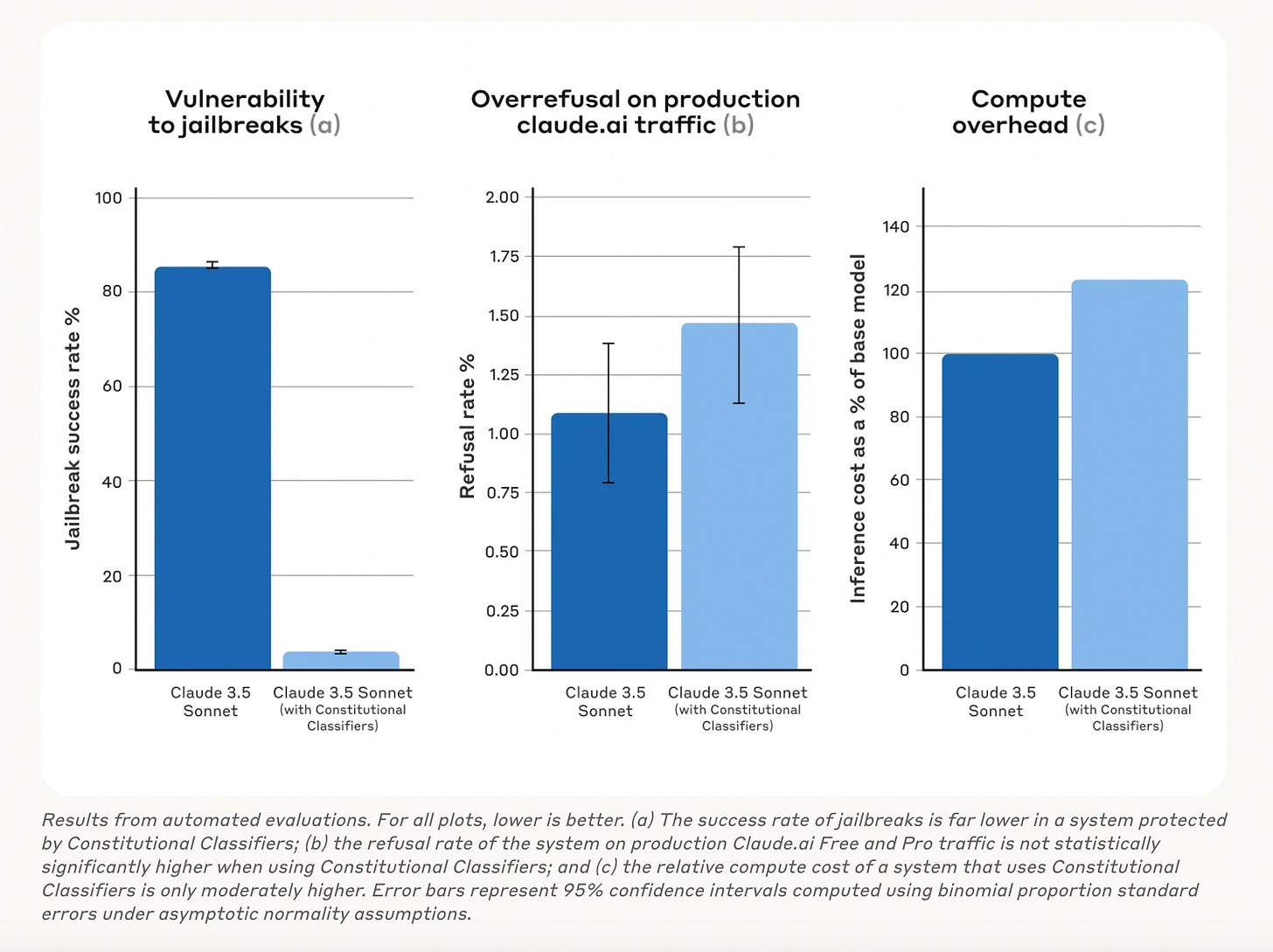

That said, like all problems in cybersecurity, it’s going to be an ongoing issue. That’s why some companies have chosen to kind of hide the chain of thought in their reasoning models, because it makes it much harder to distill. Those can be jailbroken. But folks are working on antidotes to jailbreaking. We just released something today that makes it much harder to jailbreak models.

Espionage Prevention and Cross-border Collaboration

Jordan Schneider: Setting distillation aside, when you were on the Dwarkesh podcast about a year and a half ago, you said that if it’s a state’s top priority to steal weights, they will. If we’re living in your timeline and this stuff becomes the most important thing on the planet and it attracts more attention from Beijing and other state actors, what does that do to the gap, if any, between the leading labs and everyone else?

Dario Amodei: The biggest possible gap I can imagine is a couple of years. That’s actually worth a lot for the amount of advantage it gives — it provides a buffer to us here in the US and its allies to address some of the safety problems of AI systems. A gap greater than two years isn’t feasible. We should aim for a gap of two years.

The idea of preventing state actors from stealing the most powerful models for two years is challenging — quite challenging. But it’s possible. The way to do it is to enlist help from two powerful forces: One is the United States government, and the other is the models themselves. As the models get better at everything, one thing they’re going to get better at is cybersecurity — using the models to defend themselves. Second, using the United States and its counterintelligence capabilities to prevent the models from being stolen.

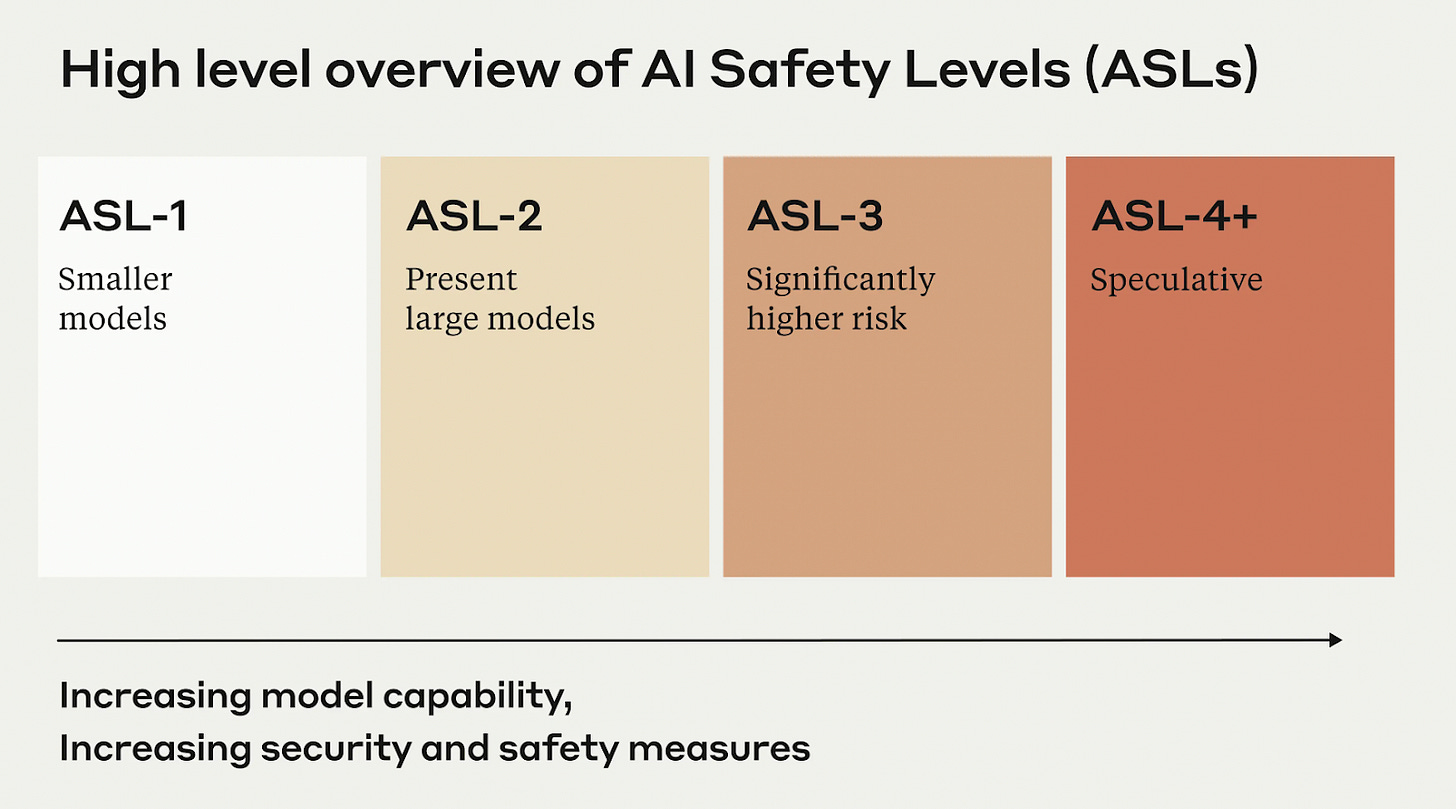

Our responsible scaling plan, our RSP, which we developed about a year and a half ago, anticipates this. It has different levels.

Currently, we’re at ASL2, which is strong but relatively ordinary for tech company security measures. The next level, ASL3, is preventing the models from being stolen by strong non-state actors. ASL4 and ASL5 are preventing theft from state actors. Those are very high bars to clear. When the model reaches certain levels of capability that we’re specifying, we have to put in place these strong security measures. A lot of what we were thinking about was this competition between the U.S. and China and the need to improve lab security.

Jordan Schneider: If the US government can’t keep Gina Raimondo’s emails safe and the Chinese can listen into every phone call in America, it seems like a tough thing to hang your hat on. Maybe another way to ask it is: say you steal the model weights — how much tacit knowledge is necessary that a DeepSeek or a ByteDance may or may not have with Opus 5 in order to make the most out of it relative to what the makers can?

Dario Amodei: Running that particular model is not that difficult. Using it to develop the next model is substantially more difficult because it’s optimized to run in some other cluster and setup in some other place. There are other things you can imagine doing.

Jordan Schneider: We’ve talked about competition from the lens of compute, from the lens of models, but models are created by people. The times I’ve been to NeurIPS, it has been really striking to me just how much Mandarin is spoken at those poster sessions. I’m curious what message you’d have to say to PRC nationals studying in the West who hear this and are like, “Why would I want to work for this guy?"

Dario Amodei: I want to be really clear on one thing — I should probably say it even more than I do. When we talk about China, this isn’t about Chinese people versus American people. Speaking for ourselves, but I suspect the other US companies would say the same, we’re excited to have talent from around the world. We have no beef with talented researchers and engineers, no matter where they work. We’re from the same community they are. If there’s some kind of cooperation to be had here, it’s probably through this kind of track-two researcher-to-researcher thing. We welcome these folks absolutely, as much as we can.

The concern here is authoritarian systems of government, wherever they exist. We could have seen in the last 10, 15 years, China could have gone down a very different route than they did. I’m not a China expert, but many people do seem to think that there was a bit of a fork in the road and maybe an opportunity for them to take a more liberalizing path. For whatever reason, that didn’t happen. But if it had happened, certainly my view on all of this would be completely different. This is not about animus against a country. This is about concern about a form of government and how they’ll use the technology.

Jordan Schneider: Well, now this interview is definitely not going viral in China. Thank you for that. Dario, anything you want to say to DeepSeek?

Dario Amodei: They seem like talented engineers. The main thing I would say to them is take seriously these concerns about AI system autonomy. When we ran evaluations on the DeepSeek models — we have a spate of national security evaluations for whether models are able to generate information about bioweapons that can’t be found on Google or can’t be easily found in textbooks — the DeepSeek model did the worst of basically any model we’d ever tested in that it had absolutely no blocks whatsoever against generating this information.

I don’t think today’s models are literally dangerous in this way. Just like with everything else, we’re on an exponential, and later this year, perhaps next year, they might be. My advice to DeepSeek would be take seriously these AI safety considerations. The majority of the AI companies in the US have stated that these issues around AI autonomy and also these issues around AI misuse are potentially at least serious and real issues. My number one hope would be that they come work in the US, they come work for us or another company. My number two hope would be that if they’re not going to do that, they should take some of these concerns about the risks of AI seriously.

Jordan Schneider: The dominant framing, how you’ve written and other folks in AI policy circles is that AI is going to be something that entrenches autocrats. People are talking about the CCP like it could turn into a thousand-year Reich. Can you see a world in which AI, and perhaps particularly open source AI, is actually sort of like a democratizing force?

Dario Amodei: I actually can and I wrote about it a bit in “Machines of Loving Grace.” I don’t really think it’s about open source or closed source. I could imagine a world where China makes powerful AI that’s open source, but they have the biggest clusters, they have the biggest ability to fine-tune the model. If I’m a citizen of an autocracy, does a flash drive with some model weights on it help me resist the autocracy? There’s this almost impressionistic connection between “oh, there’s this thing that’s available to everyone” and it’s like a freeing resource. I don’t really see that connection.

It’s similar to saying like, suppose I had the code for TikTok or the code for Twitter or something. Would that change the effects that social media had on all the people around? I don’t think that it would — this all comes from things operating at scale. What does matter is how we use the technology, whatever form it’s been produced in.

As I wrote in “Machines of Loving Grace,” I had these ideas for using AI to strengthen democracy. It’s more around the administration of justice. AI may open up the possibility of having a more uniform, more fair system of justice. The justice system often involves making judgment calls — things that are somewhat subjective and typically have to be done by a human. People worry that if you do it by an algorithm, it’ll be less fair. But if we apply it correctly, AI systems could create a fairer society — one in which people are more likely to receive equal justice under the law.

Around deliberation and democratic decision-making, there are opportunities for AI to help. We did a collaboration with an organization called Polis that used AI systems to aggregate public opinion and facilitate discussions between people to find areas of common ground. That’s something healthy for a democracy. Finding areas of common ground is really something that we want to do.

I also suspect that improving our science, improving our health, and improving our mental health across society may in lots of subtle ways improve the effectiveness of our deliberative decision-making.

“[B]oth the specific insights and the gestalt of modern AI can probably be applied fruitfully to questions in systems neuroscience, including perhaps uncovering the real causes and dynamics of complex diseases like psychosis or mood disorders.”

~ Dario Amodei, “Machines of Loving Grace”

Jordan Schneider: You wrote two blog posts and they seem to be in tension with each other at some level. One-sixth of humanity lives in China. How do you think about that in the context of your sort of vision of AI enabling more human flourishing?

Dario Amodei: I actually think these are part of a single worldview. In fact, in “Machines of Loving Grace,” in the section on AI and democracy, I say we need to lock down the supply chain. Export control is obviously part of what I meant by that, lab security and semiconductor equipment being other parts of it. These actually are deeply compatible.

First of all, I think it’s perfectly possible to distribute the benefits of AI to all the world, including China, including other authoritarian countries, without distributing the military capabilities. If you have a powerful model and you’re just handing over the powerful model, then yes, they all come together because it’s a generalized dual-use technology. But you can take a model, you can run it via API, and you can serve it to China for drug development, for the next cancer drug. You can serve it to China for more efficient energy production. Basically, you can rent very large amounts of the model’s time to someone in China for these economically productive activities.

I think that’s a useful form of trade. That should happen. Through that, you can have all the benefits of AI shared, but at the same time, you can just block usage of the model if someone’s asking about how to make a hydrogen bomb with the model, or someone’s asking how to find and target nuclear submarines, or R&D for orbital weapons or something. You can block those applications while allowing the ones that are really good.

Now, there’s kind of a bigger picture here, which is that in the long run, we’re going to want all the uses of AI to go to everyone. We’re going to have to work out, in the long run, some kind of international governance of the technology, some kind of stable equilibrium. Because I said that the US lead at most will be two years. My hope is that that will go better if the US is leading the setup of that international regime. It will go better if we’re able to negotiate for safe deployment for everyone from a place of strength. If we’re doing it from a place of weakness, the worry is we’ll just get dominated.

I think the US is in a position to make some more magnanimous decisions here if it has the lead. We should start thinking now about what we should do. The plan isn’t just like, crush our adversaries. I don’t think that would even work. The plan has to be some version of, start from a position of strength, and work out how this technology can benefit the whole world and how its downsides can be mitigated.

Jordan: Dario, if this AI stuff doesn’t end up working out for you, I think you might have a chance to make it as a substacker. Thanks so much for being a part of ChinaTalk.

This was great!

The outro song is just *chef's kiss*, wow.