How has Chinese hegemony shaped power relations in East Asia? Why did imperial China conquer Tibet and Xinjiang but not Vietnam or Korea? Can learning from history help maintain peace in the Taiwan Strait?

Today’s interview begins with a striking observation — while medieval Europe suffered under near-constant war, East Asia was defined more by great power peace.

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Professor David C. Kang, director of the Korean Studies Institute at USC and co-author of Beyond Power Transitions: The Lessons of East Asian History and the Future of U.S.-China Relations.

We discuss…

How East Asian nations managed to peacefully coexist for centuries,

Why lessons from European history don’t always apply,

How to interpret outbreaks of violence in Asia — including conflicts with the Mongols, China’s meddling in Vietnam, and Japan’s early attempts at empire,

Whether the Thucydides trap makes U.S.-China war inevitable,

Old school methods for managing cross-strait relations.

Co-hosting today is Ilari Mäkelä of the On Humans podcast.

Have a listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

Power Transitions in East Asia

Ilari Mäkelä: Professor Kang, what do you think people unfamiliar with East Asian history often get wrong about international relations and war?

David C. Kang: When great powers stumble, it’s often due to internal reasons rather than external threats or wars. To me, that’s the most important yet least widely known lesson from East Asian history.

Ilari Mäkelä: Your argument about about East Asia — the region comprising China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam — is striking. These states formed clear national identities by the end of the first millennium. From that point on, territorial conflicts between them were rare. Compared to the almost constant warring in Europe, East Asia’s history seems remarkably peaceful, according to your book.

David C. Kang: Exactly. It’s not that East Asian countries never fought — they did, sometimes fiercely — but the nature of those wars and the dynamics of territorial disputes were very different from what we see in European history.

Because of European history, territorial expansion, violent power transitions, and power grabs are often seen as inevitable and universal aspects of human nature. But in East Asian history, those types of interactions are not the norm.

What kinds of power transitions do we see in Asia, then? This is a central question my co-author Xinru Ma and I explore in the book. Most people try to squish European historical frameworks onto Asia, asking if China today is most like Athens, Sparta, or Bismarckian Germany. We challenged that approach. Why not start with Asian history and see what parallels emerge?

If you began your study of international relations with Asia instead of Europe, you would never come up with a theory of power transitions, of rising and falling powers grabbing land and exploiting tiny advantages. Instead, you’d observe a system of remarkably stable states with clear national identities. Korea was clearly not China, and it was clearly not Japan. These states were unequal in terms of power, but they managed their relationships in ways that respected those differences.

The other key insight is that nearly every dynastic transition in East Asia stemmed from internal collapse, rebellion, or decay — not external invasion. When you look at the collapse of dynasties like the Tang, Ming, or Qing, the reasons are overwhelmingly internal. Remarkably few changed because of external invasion.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s dive into specifics. How did the Mongols manage to conquer the Song dynasty?

David C. Kang: Over the last 2,000 years, there are few examples of China being conquered by an external force. But the Mongol victory over the Song in the 13th century is one of those rare examples. On the surface, it looks like a classic power transition — a rising power (the Mongols) overtakes a declining power (the Song). But when you dig deeper, the reality is far more complex.

At its height, the Song dynasty was an incredibly powerful, wealthy, and dynamic state. It had a population of 50 million and a standing army of three million soldiers. The Song pioneered paper money, developed an extensive canal system, and achieved remarkable cultural and technological advancements.

In contrast, the Mongols were a relatively small group. Even at their peak, their population was around one million, maybe less. How did they conquer such a powerful state? It wasn’t because they were a “rising power” in the traditional sense — it was because of the Song dynasty’s internal mismanagement.

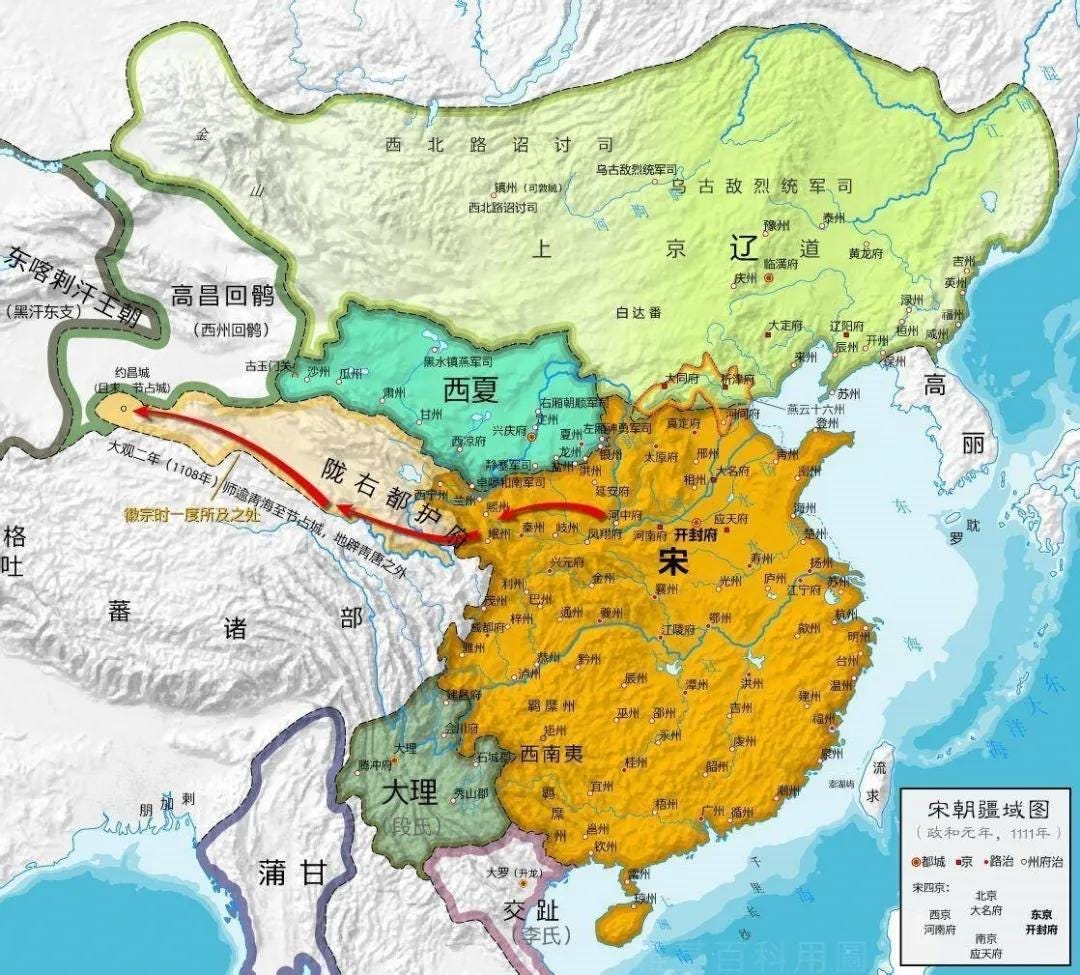

For decades, the Song leadership was obsessed with reclaiming the “Sixteen Prefectures” 燕云十六州 in the north, territories they had lost to the Liao dynasty. This obsession blinded them to the real threat posed by the Mongols. In fact, the Song even tried to ally with the Mongols at one point, thinking they could use them to recover their lost lands.

By the time they realized the Mongols were the greater threat, it was too late. The Mongols exploited the Song’s internal divisions and strategic missteps, ultimately conquering them and establishing the Yuan dynasty in 1279.

In many ways, the Song-Mongol transition doesn’t look anything like what we would expect a power transition to look like. Instead, Song China focused on what it believed to be its own inherent territory, and didn’t pay attention to actual threats.

Jordan Schneider: The Song had no business losing, but they were just so emotionally bound up in their connection to these northern territories that they just made a lot of dumb decisions that opened them up to conquest. But the Mongols didn’t just conquer the Song — they built the largest contiguous empire in history. Do the Mongols deserve some credit for this conquest, or was it a completely self-inflicted defeat on the Song’s part?

David C. Kang: The argument isn’t just that the Song just screwed up and the Mongols got lucky. The Song leadership wasn’t looking at the broader picture and thus let the fox into the hen house.

That isn’t to take away credit from the Mongols per se. Genghis Khan and his successors were extraordinary strategists. But the goal here is to think about how we should categorize this event — it didn’t really look like a power transition in the traditional sense.

By the time the Song realized the true scope of the Mongol threat, decades of evidence had already shown how powerful the Mongols were. Yet the Song continued to focus on reclaiming lost territory. The Song had already been divided into two because they were so focused on fighting to reclaim these prefectures that they had lost to the Liao — they had already been pushed back and become the Southern Song.

In the book, we tried to avoid the term “national identity” because that’s way too modern — bt there was some conception of what Song China should be, and it was longer, older than the Song itself. That’s what they were focused on until way too late.

“What is civilization? What does it mean to be Chinese? Oh, wait, the Mongols are attacking us.”

Ilari Mäkelä: Another interesting point you made about the Mongols — there’s a big difference between the events that happen in China’s east vs in China’s west. The Mongols are just one example of the troubles on China’s western frontier. This is, after all, the very reason the Great Wall was built.

What’s striking, though, is how differently the story unfolds in East Asia. On China’s western frontier, there’s a constant threat of violence — if not outright war, then at least persistent instability. But on the eastern and Vietnamese fronts, particularly from the emergence of the Vietnamese state around the year 1000, we see a different pattern. There’s a notable stability, with one major exception when Japan goes on a rampage against Korea and China. We’ll get to that, but before we do, can you elaborate on how Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and China formed a system that’s remarkably distinct from what we see not only in Europe but also on China’s western frontier?

David C. Kang: Certain ways of thinking about the world get codified as conventional wisdoms, to such an extent that we even stop questioning them

First, let’s talk about history. The “lessons of history” that we often hear about — the gladiators, Athens, Sparta, the Crusades — are almost exclusively drawn from Europe. That’s fine, but it narrows our perspective. Second, even when historians talk about China, they focus overwhelmingly on the threats from the west — the nomadic peoples of the steppes, like the Mongols or the Xiongnu, who lived on the Great Plains thousands of years ago. The Great Wall is the enduring symbol of this focus on western threats. Disney’s Mulan defending China from the barbarians is probably the most widely known impression of Chinese history. But when you dig deeper, it’s fascinating.

Western theories of international relations — whether it’s the “game of Risk” or formalized theories of power dynamics — usually assume that larger countries bully smaller ones. But with China, we focus on how this massive civilization was constantly threatened by smaller, nomadic peoples. That shouldn’t make sense, right?

If you imagine a country of 50 million people with a powerful bureaucracy and military, surrounded by smaller polities, you’d think the smaller polities would be terrified of it. Yet, China was building walls to protect itself. It’s the smaller neighbors that should have been fortifying against China, not the other way around. The US-Mexico border wall is a modern parallel to this, but we’ll discuss that later. But the point is, we take for granted that China was being threatened.

Then there are the eastern and southern frontiers, where the dynamic is entirely different. These were not nomadic tribes but settled agrarian kingdoms — recognizable “nascent states” like Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. They had established territories, bureaucratic administrations, and written languages. They used Chinese characters, and their governance systems were inspired by Chinese models. These were fully functional governments, not roaming tribes.

By all accounts, Korea, Japan and Vietnam should have been terrified of China. But they weren’t building walls to protect themselves. Instead, they developed remarkably stable relationships with China — and with each other.

Now, in a way, this shouldn’t be surprising if we allow ourselves to move away from what “should” happen based on the European example. We have a bunch of countries — some are bigger, some are smaller, but they all have similar goals. A shared understanding emerges, and I mean that literally. They could all understand each other because they all wrote with Sinitic scripts. The Japanese originally wrote only with Chinese characters (kanji), and then invented syllabaries based on modified Chinese characters.1

The Koreans originally wrote with Chinese characters called hanja, and the Vietnamese used Chinese characters plus additional characters of their own in a system called Chu-nôm. 60 to 70% of the vocabulary in these languages is borrowed from Chinese words.

But more than that, these smaller states were consciously trying to be like the Chinese. They adopted systems like the Six Ministries, civil service examinations, and Confucian bureaucratic practices. China’s influence provided a template for stability and organization.

So in a way, if we start from that, it’s not surprising that these countries could craft stable relations with each other. They had, what we call in the book, a common conjecture. All sides — Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese and Chinese — had a common vocabulary and a common understanding of what mattered. That doesn’t mean they always got along. There was lots of pushing and shoving, but it was within a shared understanding of what the world meant and how to handle disputes.

This is very different from China’s relations with the nomadic peoples to the west, like the Mongols and Xiongnu. Those groups didn’t share the same cultural or political aspirations. The Mongols weren’t necessarily interested in building bureaucratic systems or adopting Confucian ideals until they conquered China. They ruled as the Yuan dynasty for about 100 years and maintained the civil service exam, but the Yuan eventually fell apart because bureaucracy was fundamentally foreign to the Mongol way of life.

In contrast, the relationships between China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam were built on shared understandings and mutual recognition. This led to very different patterns of interaction — markedly more stable than what we see in Europe or on China’s western frontier.

When we talk about international relations, it’s not simply a question of who has the most relative power. We should also be asking, “Do we understand each other? Do we have a common culture and vocabulary? Are we all part of the same Great Conversation?”.

Ilari Mäkelä: This history wasn’t always rainbows and butterflies — but the civil service exam did seem to usher in a long era of peace.

When Jordan and I interviewed Yasheng Huang, we discussed how the civil service exam shaped China. Your work shows it wasn’t just China that was impacted — Japan, Korea, and Vietnam also emulated this civil service system. The Sui Dynasty institutionalized this system, but they also attacked Korea several times. But after the civil service system took hold across these regions, we see long-term peace emerge.

That’s particularly important in the case of Vietnam. Many Vietnamese today argue that China was always a bully. Your research, however, suggests a different story. While there was conflict at certain points, once Vietnam adopted the civil service system and developed a state from roughly the year 1000 onward, the dynamic changed. This seems to mark a distinct shift in their relationship, resulting in remarkable stability.

David C. Kang: Exactly. One of the ways in which Vietnam, for example, maintained its independence was by instantly entering tributary relations with China’s Song dynasty once it gained independence from Chinese rule around the year 1084.

I’m currently researching the Ming Shilu 明實錄 and the Qing Shilu 清實錄, the veritable records of the Ming and Qing dynasties from about 1400 to 1900. I’m particularly interested in how the elites in Beijing discussed Vietnam. Modern Vietnamese nationalists often say, “China was always bullying us and trying to invade.” But when you look at the historical records, the story is different.

When rebellions occurred in Vietnam, factions would appeal to the Ming or Qing courts, asking to be recognized as the legitimate rulers. Chinese elites would then debate who to recognize, how to stabilize the relationship, and how to avoid disruption. There’s almost no discussion in the Qing historical records about invading Vietnam or annexing it. It’s all about maintaining stable relations and deciding which faction to recognize as the legitimate government.

On the Vietnamese side, Chinese recognition often legitimized a faction’s rule domestically. The formal border between Vietnam and China, first negotiated in 1084, is still in the same place today. That’s almost a thousand years of stability. They even placed bronze pillars to mark the boundary, as described in Liam Kelly’s excellent book, Beyond the Bronze Pillars. Those markers have endured, underscoring the remarkable longevity of this arrangement.

Jordan Schneider: I’d like to push back on this a little bit. When comparing East Asia to Europe, it seems that at the end of the day, you have China as the dominant power and smaller polities figuring out how not to get squished. Some, like Vietnam and Korea, succeeded and survived, while others, like Tibet and Xinjiang, were subjugated and absorbed.

In regions like Yunnan, there are no longer any independent kingdoms. Tibet and Xinjiang have had particularly rough histories, with various ethnic minorities once doing their own thing but eventually being subsumed. By contrast, perhaps Vietnam, Korea, and Japan were just far enough away, geographically remote, and, perhaps, not important enough to China to justify military campaigns.

Is it fair to say that these dynamics helped Vietnam, Korea, and Japan maintain their independence? Did the Chinese view the tribute system as sufficient payoff — bringing them symbolic gifts like cows and inscriptions while allowing these states to govern themselves?

What really drove this home for me was a quote from a scholar you cite:

Over the centuries, Korean elites, as stakeholders rather than outsiders, helped shape the imperial tradition. The palpable irony of all this is the myth of China’s moral empire has persisted even until today, partly because generations of Korean diplomats had been repeating it to China’s imperial forebears for centuries... But to come away with this conclusion is to forget why Korean envoys and memorial drafters used the notion of moral empire in the first place: it was to convince emperors and their agents that behaving according to Korean expectations was the best way to be imperial.

This dynamic reminds me of something I recently reflected on during Yom Kippur. Many Jewish prayers essentially remind God of His promises to be nice and to practice forgiveness. Similarly, Korean envoys were telling Chinese rulers, “This is how you should act if you’re truly the moral empire.” If you look at it from a national power perspective, these smaller states didn’t have a lot of choice given that China was 100x bigger than they were.

From the Yom Kippur Amidah:

And You, Lord our God, have lovingly given us this Yom Kippur for pardoning, forgiving, and atoning – to pardon all our iniquities – a sacred occasion commemorating the exodus from Egypt…. Our God and God of our forefathers: pardon our iniquities on this Yom Kippur; wipe away and remove all our transgressions and sins from before Your eyes, as it is said: “I, I am the One Who shall wipe away your transgressions for My sake, and I shall not recall your sins” (Isaiah 43:25). And it is said: “I have wiped away, like mist, your transgressions, and like a cloud, your sins; return to Me, for I have redeemed you” (ibid. 44:22). And it is said: “For on this day, atonement shall be made for you to purify you of all your sins; you shall purify yourselves before the Lord” (Leviticus 16:30). For You are the Forgiver of Israel and the Pardoner of the tribes of Yeshurun in every generation, and without You we have no king who pardons and forgives but You. Blessed are You, Lord, King Who pardons and forgives our iniquities and those of all His people the house of Israel, and removes our guilt each year, King of all the earth, Who sanctifies Israel and Yom Kippur.

Could it just be historical happenstance that Vietnam, Korea, and Japan realized early enough that they needed to carve out a role as fawning foreigners if they wanted to avoid being squished? What are your thoughts?

David C. Kang: You’ve captured one of the book’s key arguments — this system wasn’t about relative power. It was about a shared understanding of how to behave and interact. Relationships were built on norms and expectations, not just power calculations.

In real life, people — and states — don’t constantly carry figurative knives, ready to stab at the first opportunity. Instead, there’s a basic understanding of what is acceptable and expected behavior. This “great conversation,” as we call it in the book, allowed these countries to coexist.

By the way, that passage you read was from a brilliant book written by Sixiang Wang. But this is the discussion. It’s not that somehow under the Sui dynasty in 500 AD, they came up with a bunch of rules that everybody just then followed for the next 1500 years. No — this system was constantly being adjudicated and adjusted, as you pointed out.

Jordan Schneider: But the only reason you can even have this conversation in the first place is because that relative balance of power doesn’t change. The fact that China was a thousand times more powerful than these other states was the constant that gives rise to the understanding you’re describing.

David C. Kang: You’re absolutely right. Europe was a multipolar balance of power system. It was and it still is today. Asia has and is a unipolar, hegemonic system — it’s got one massive power and a bunch of smaller countries, so these continents are not going to behave in the same way. From the first time China was unified, almost 2000 years ago, all the other countries had to figure out how to survive and exist and pursue our goals in the shadow of an enormous central power. They weren’t focused on expanding their territories. The fact that they were stuck meant that they had to work out how to behave in this unequal relationship.

People in DC talk aspirationally about how small Asian nations are going to band together as a counterbalance to China. That is never going to happen. The countries in Asia are not going to join a US containment coalition against China. That’s not how it’s going to work. They have to live with China. They don’t have to like it, but they have to craft a relationship with this massive country — which is really what they’ve been doing for centuries.

Japanese Bids for Hegemony (脫亞入歐)

Ilari Mäkelä: Korea stands out as a poster child for this kind of stable relationship with China. The Vietnamese viewpoint often pushes back by saying, “No, China was always trying to invade.” But many of those conflicts, like the rebellion led by the Trưng sisters 𠄩婆徵, happened before the sinification of Vietnamese culture.

Japan is an interesting case. Besides its wars with China and Korea in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there’s the period in the late 1500s when East Asia erupts during the Imjin War. I suspect most listeners haven’t even heard of it — it wasn’t on my radar before reading your book. Things really went wild during that time. Could you share the story of the Imjin War and discuss whether Japan, in some ways, behaved more like a European power?

David C. Kang: First, let me say that part of what has made this work so engaging over the past two decades is how much it challenges the way we teach international relations in the U.S. and Europe.

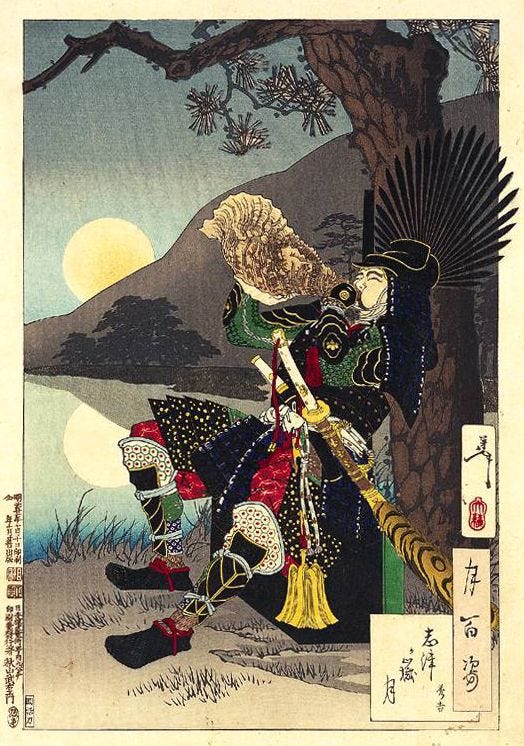

I grew up hearing stories from my father, who was from north of Pyongyang. He would talk about how the Japanese kept trying to invade Korea and how they were fought off with turtle boats. I didn’t pay much attention as a kid, but I vaguely knew about Admiral Yi Sun-sin, “the turtle boat guy.” That was the extent of my knowledge of Korean history before I started this research.

Admiral Yi Sun-sin deserves to be studied in every international relations course. He was an extraordinary admiral who, with just 13 ships, defeated fleets of 300 Japanese vessels during the Imjin War. But beyond Yi’s brilliance, the war itself is worth studying because it doesn’t follow the patterns we expect.

Everyone knows about the Spanish Armada of 1588 — the largest force Renaissance Europe had ever seen, with 130 ships and 20,000 troops aimed at invading England. But just four years later, in 1592, on the other side of the globe, Japan attempted to invade China by first conquering Korea. Hideyoshi’s campaign mobilized 300,000 Japanese troops and 700 ships — a force five to ten times larger than anything Europe could imagine at the time. The scale of warfare in East Asia dwarfed Europe’s during this period.

Ilari Mäkelä: Why is that? Was it because of Japan’s civil service system?

David C. Kang: Yes. It comes back to the civil service system and the organizational capacity it enabled. Consider that in 700 AD, Japan’s central government employed about 7,000 bureaucrats. By comparison, 500 years later, the Catholic Curia in Europe had only about 500 officials. That was one of the most organized institutions in Europe at the time. Also consider that at the time, Japan was considered to be less organized, less sophisticated, and more barbaric than Korea or China. Yet Japan still had a bureaucracy that far surpassed anything in Europe.

These East Asian countries had the capacity to raise massive armies and fleets when they chose to. China, for instance, always maintained a large army due to the persistent threat from the western steppe nomads. But when these countries decided to go to war, their logistical and organizational capabilities were staggering.

That brings us to the Japanese invasion of China by general Hideyoshi. There had been a breakdown of central rule in Japan for about 100 years. Hideyoshi first unified Japan, and then decided to invade China.

As we pointed out, China was bigger than Japan. Why did Hideyoshi invade then? Ego is certainly one reason. Another theory is that the campaign was motivated by domestic politics. By sending the armies of the newly unified daimyo abroad, Hideyoshi may have been trying to prevent internal revolts and secure their loyalty through the promise of loot and land.

“It is not Ming China alone that is destined to be subjugated by [Japan], but India, the Philippines, and many islands in the South Sea will share a like fate.”

~ Hideyoshi writing to his adopted son in 1592

What’s clear, though, is that Hideyoshi didn’t conduct any meaningful strategic assessments of the relative balance of power between Japan, Korea, and China. There’s almost no record of the kind of calculations we associate with the start of wars in Western theories of international relations.

Instead, he ordered Korea to allow his forces passage to China. When Korea refused — because they thought the demand was absurd — Japan launched a massive invasion in 1592.

IR theory indicates that in a situation with one big country and two small countries, the two small countries should form an alliance against the big country. But that’s not what happened. Instead, Japan invaded Korea, who was not expecting it. The Koreans were aware of Japanese military buildup for a couple of years, but they essentially refused to believe Japan was planning an invasion.

Eventually, they asked China for help. China sent troops to support Korea, and together with Admiral Yi Sun-sin, they pushed the Japanese back to Busan. Negotiations dragged on for a few years, the Japanese attempted a second invasion which was crushed.

Now, the Korean government would not have survived if the Chinese weren’t there. The Chinese troops were completely in charge of the Korean peninsula after this war. All they had to do was say, “Okay, we’re in charge. This is now the newest province of China.” But they didn’t do that. Within about a year, the Chinese troops all went home. The Koreans were actually trying to get the Chinese to stay because they thought the Japanese might come a third time, but China basically said, “This isn’t our country — this is Korea. Good luck.”

The Japanese slinked home and the system snapped back to stability after Hideyoshi’s death, and Japan entered a period of isolation under the Tokugawa shogunate for the next ~300 years.

But this was the only war between Japan, Korea and China in the 600 year period from 1200 to 1800.

Ilari Mäkelä: Perhaps the Imjin War is the strange exception that proves the rule of stability.

But that same rule doesn’t hold when we look at the much more familiar examples of Japan attacking China in the late 1800s and, of course, during the world wars. One of the key points we discussed earlier with Jordan was how major international relations theories, like the so-called Thucydides Trap, tend to be too Eurocentric. This theory posits that when a rising power challenges an established one, war is almost inevitable— citing that 12 out of 16 such cases in history have led to war.

You argue this pattern doesn’t apply to East Asian history, and that’s fair enough. But some might say this is simply because no power in East Asia was able to meaningfully challenge China. As Jordan mentioned earlier, the moment Japan industrialized and became capable of challenging China’s hegemony, it did so.

Lo and behold, Japan behaves exactly like the Western IR theorists would predict Japan to behave.

How do you see East Asia as either a counterexample to the Thucydides Trap or, alternatively, a case that supports it? Could it be that East Asia’s history simply lacks sufficient examples of power transitions, leaving us with only one — Japan — and in that instance, Japan behaved exactly as Western international relations theorists would predict?

David C. Kang: That’s a great question. This is what makes the topic so fascinating. You had a traditional East Asian world order with its own principles, values, and expectations, and it was, as we’ve been discussing, remarkably stable. The arrival of Western imperial powers in the 19th century shattered that stability.

I think this era is particularly crucial for international relations scholars interested in understanding how world orders change. There are fascinating examples of Japan adopting Western theories and practices, even learning French to communicate with Western powers. By 1879, Japan was arguing with China over Taiwan, using Western-style legal frameworks like contracts, while China clung to the tributary system and its associated norms.

The Chinese perspective was rooted in its historical system, speaking in Chinese and adhering to traditional principles. The Japanese, on the other hand, were adopting Western concepts and were baffled by the Chinese resistance. These were literally different worldviews clashing, and they didn’t understand each other anymore.

One of the most fascinating areas of research is why Japan adapted more successfully than China. To put it simply, China, as the hegemon, had little incentive to change, while Japan, recognizing its vulnerability, was eager to learn. Japan borrowed German military practices, English business models, and other Western systems with remarkable speed.

When we look at the actual wars, though, I wouldn’t necessarily call them power transition wars. Japan’s expansion was as much about ensuring its own survival as it was about challenging China. Japan had more time to adapt because it wasn’t as valuable a target as China. For Japan, the central question was, “How do we become a great power?”

Great powers had flags, colonial possessions, militaries, and modern institutions. Japan adopted these markers of power. There’s even this striking image from the 1870s of the Japanese emperor from the dressed like Bismarck, complete with a sword, medals, and a mustache.

Japan’s transformation wasn’t just about competing with China—it was about being recognized on equal footing with Western powers. For example, Japan’s push for a racial equality clause at the League of Nations in 1919 was part of this broader effort. Half of Japan’s actions were aimed at asserting itself in the Western-dominated international system, while the other half focused on recalibrating its relationship with China.

If you don’t look too closely, it might seem to fit the Thucydides Trap. But when you examine Japan’s motivations, they seem driven as much by survival in a Western-dominated world as by any transition of power with China.

Ilari Mäkelä: Okay, fair enough. But your book is titled Beyond Power Transitions, so we can’t let you off the hook that easily.

It might be possible to offer alternative explanations for some of these cases, but it’s another thing entirely to argue that East Asia doesn’t support power transition theory. Traditional international relations scholars might counter that East Asia simply hasn’t experienced many examples of power transitions. When one finally occurred—Japan’s rise—it followed the typical pattern of conflict.

Even if East Asia shows remarkable examples of peaceful coexistence, it doesn’t demonstrate that power transitions can occur without war.

David C. Kang: Fair enough. This brings us to a broader question: has the entire world adopted the Westphalian system? Have nation-states, balance of power politics, and sovereignty — hallmarks of the European model—become universal? If the answer is yes, then debates about the applicability of power transition theory become relevant.

But I argue this transition is superficial at best. One of my critiques of power transition theory is that it claims to be universal. In our book, we try to “regionalize” power transitions, essentially arguing that what’s seen as universal is actually specific to Europe.

In East Asia, we didn’t see the same beliefs or behaviors. The question now is how much Asia has truly changed.

When it comes to Japan specifically, I don’t think Japan ever matched China’s strength, even in the 19th century. It may look like Japan was rising while China was declining, but if you examine the metrics — population, resources, or military capacity— China was always larger and more powerful.

So I’m not convinced Japan’s rise constituted a power transition. It might look like it on the surface, but China was never as weak, nor Japan as strong, as some narratives suggest.

Ilari Mäkelä: But hold on. Do you think China could have defeated imperial Japan during WWII without U.S. support?

David C. Kang: Remember the line from The Princess Bride, “Never get involved in a land war in Asia.” Japan was already bogged down long before the U.S. became deeply involved in the conflict.

I’m not sure Japan ever had the capacity to conquer China, even in the 1930s. The war looks more like an imperial project aimed at securing Japan’s survival than an opportunistic move against a weakened China.

But let me be clear — Japan’s achievements were extraordinary. It was the first non-Western country to industrialize and the first to defeat a European power in war, with its victory over Russia in 1904. I don’t want to diminish Japan’s accomplishments or the threat it posed.

Still, the dynamics of Japan’s rise don’t fit neatly into the framework of a Thucydides Trap. It’s more complex than a simple transition of power between two nations.

Jordan Schneider: Over the course of the thousand years we’re discussing, how do you think about China’s westward imperial expansion of all those neighboring civilizations that didn’t Sinicize fast enough? It’s hard to generalize across such a long period, given the particularities of Xinjiang, Tibet, Yunnan, and other regions. But for places like the Uyghurs’ homeland or others, what went differently? Did they decide not to follow the South Korea or Vietnam playbook? Or was the farmland simply too appealing to resist? What’s the key explanatory factor here?

David C. Kang: There are two possible explanations, and I lean toward the cultural one rather than the material one. The material explanation would argue that the farmland was better, or that it was easier to ride horses into those areas, or that some other geographic factor dictated the outcomes. But I suspect there’s more to it than that.

The cultural explanation is that those groups kept butting heads with the Chinese, which led to fighting. There’s a great quote in the book by a scholar who focuses on the western steppes. He noted that the nomads and the Chinese had very clear conceptions of who they were and what they wanted, and that the nomads did not want to change their way of life.

Even today, you see occasional glimpses of this with modern Mongolians — living in yurts, riding horses, moving up into the hills during summer and back down during winter. Part of the answer lies in the fact that these groups didn’t want what the Chinese wanted. They had incompatible worldviews and they knew it.

Ilari Mäkelä: Let me push back on that. There’s a third, or perhaps an in-between explanation. Consider that there are essentially two types of western frontiers for China. One is the Himalayas, where you see some stability in what we might cautiously call Tibetan statehood. The other is the famous steppe.

If you lived on the steppe, you were essentially living off grass. Humans can’t eat grass, so you needed animals that could convert grass into something usable. Grass, being a low-energy resource, necessitated a nomadic lifestyle, requiring vast areas to sustain people and animals. This lifestyle inherently shaped culture.

The demands of the steppe way of life dictated horse riding, mobility, and a fundamentally different worldview. In such an environment, cramming Confucian classics for a civil service exam to run granaries for famine relief just didn’t make sense. It’s not that the steppe people couldn’t adopt Chinese-style governance; it’s that their material realities didn’t allow for it. The steppe experience, in this sense, is largely shaped by energy poverty and material demands.

David C. Kang: That’s a valid point. There are definitely material explanations, but I also think it’s important to recognize that these groups liked the way they lived. There might have been room for compromise — by trading goods, for example — but they didn’t fundamentally want to change their way of life.

I will admit that I’m not a steppe scholar. I’ve been more focused on trying to explain the stability on the Eastern side, which is relatively understudied.

Jordan Schneider: I see what you mean. But what about regions like Yunnan or Sichuan? These areas, taken over by China between roughly 1000 and 1500, don’t fit into the steppe-nomad narrative. They didn’t have steppe-style grassland landscapes, and yet imperial China absorbed them completely.

Ilari Mäkelä: Well, Sichuan had a lot of farming, and thus needed granaries and bureaucrats to manage decisions about how and where to store the grain.

Jordan Schneider: That’s what I’m saying. In these areas, you had dozens of small kingdoms and cultures. Yet, looking westward, virtually all of them were unable to maintain their independence and eventually absorbed into China.

David C. Kang: That’s a great observation. When I teach this, I often ask students to imagine a country that starts with a populated, urbanized, and sophisticated eastern seaboard, then expands westward into less organized and less institutionalized inland areas. As it expands, it tends to overwhelm or displace indigenous peoples. There are at least two countries that fit this description — China and the United States.

This process of expansion is fairly straightforward. Frontiers eventually become borders, as they did when China met Russia or the Himalayas. This pattern of turning frontiers into borders has been a consistent feature of global history for the past 10,000 years.

In the case of China, this expansion westward often involved sparring with Tibet or other groups for centuries. During the Tang Dynasty, for example, China fought and negotiated with Tibet repeatedly. There was a constant cycle of Tibet gaining independence and then being conquered by China and then becoming independent again. As the frontier moved further west, nomadic peoples were pushed back until there was nowhere left to go.

China tried many strategies to deal with the frontier — building the Great Wall, bribing nomads with goods, or engaging in military campaigns. Eventually, it incorporated these regions into its territory as it moved farther west.

In many ways, this isn’t unique to China. It mirrors what the United States did during its westward expansion. I wouldn’t necessarily place a moral judgment on it, but it’s a process that has happened repeatedly in history.

Why History Matters for Taiwan

Ilari Mäkelä: Let’s connect this to modern times. It’s always fascinating to learn from historians, but what does this have to do with whether world war breaks out if an American ship bumps into a Chinese ship in the Taiwan Strait?

David C. Kang: The most important lesson from history is that we need to question whether the power transition dynamic is truly the most critical framework for understanding Asia today. It’s widely assumed — especially in Washington, D.C. — that the U.S. is in decline, China is rising, and this dynamic of rising and declining powers is the primary driver of events in Asia.

Our book challenges this assumption. We argue that this might not be the most important factor at all.

For example, if you look at Korean dynasties, every single one—Shilla, Goryeo, Joseon—fell due to internal reasons. The same holds for Vietnam and even for China. While the Song Dynasty was conquered, the Tang, Ming, and Qing all collapsed primarily because of internal dynamics. To paraphrase Arnold Toynbee, empires die by suicide, not murder.

This idea has contemporary relevance. Much of the debate about China today revolves around two questions. First, will there be a power transition? Second, does China want to dominate the world? But just as pressing is the question of whether China might collapse under its internal pressures.

Xi Jinping likely wakes up far more concerned about internal issues — economic challenges, the real estate crisis, demographic shifts — than about planning territorial expansion. To me, the core takeaway from our research is that internal dynamics are likely far more consequential than external ones in shaping East Asia’s future.

The second lesson relates to the shared understanding or common conjecture among East Asian countries. From the Opium Wars in the mid-19th century until about 1979, China went through a period of internal chaos. What we’re witnessing now isn’t a rise but a return.

East Asian countries have long dealt with the presence of a large, powerful China. This isn’t new. They’ve had to navigate relationships with a massive neighbor, and they’ll continue to do so.

One of the biggest mistakes American policymakers make is trying to force these countries to choose sides, often in a binary, “with us or against us” fashion. This doesn’t align with how Asian countries operate. Vietnam just joined the BRICS bloc, and Thailand is moving in similar directions. These countries don’t align perfectly with China, but they’re also not unequivocally siding with the U.S. and completely decoupling.

East Asian nations have a nuanced, pragmatic approach to dealing with China, rooted in shared understandings of history and geography. For example, I don’t think any serious Korean, Vietnamese, or Japanese policymaker truly believes that China intends to invade and conquer their countries. That doesn’t mean they’re entirely comfortable with China, but they don’t act as if a Chinese invasion is imminent.

Jordan Schneider: The modern PRC has some imperial legacies. It operates within roughly the same geography and landmass. But earlier, we discussed how rapidly Japan went from coexisting peacefully with China to cosplaying Bismarck. How do you interpret this in the case of China? Because of course, Mao didn’t want peaceful coexistence. He wanted global revolution. He funded revolutions in South America, Angola, and other areas. He threatened nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

To what extent is the modern PRC influenced by its historical identity versus following an entirely new trajectory?

David C. Kang: This is a critical question, and I don’t think we ask it enough. Is modern China fundamentally the same as the China of two centuries ago?

Most of my Sinologist colleagues would answer without hesitation that it’s completely different. They point to the CCP, Xi Jinping, and modern frameworks like “one-party authoritarianism” to explain contemporary Chinese foreign policy. They view the Communist Party’s desire to maintain power as the primary driver of China’s actions.

I’m not so sure. This is the question we need to ask because, while modernity shapes us all, there are continuities in China’s interests that transcend dynasties.

Everybody is a citizen of some nation. Most people have passports. We’ve internalized the nation-state system, a hallmark of modernity. The Chinese national anthem sounds more like something composed in 1870s Vienna than Beijing opera. These are markers of how China, like everyone else, lives in a modern, Westphalian world.

But what’s fascinating is how many of China’s foreign policy interests are what I call “trans-dynastic.” These are not new concerns, nor are they unique to the CCP or even to the KMT before it.

Take Taiwan. The Qing Dynasty explicitly told Japan that if they took Taiwan, it could permanently sour relations. The issues with Hong Kong trace back to the British takeover around 1841. These interests aren’t just CCP policies — they’re rooted in a much longer historical tradition.

Some scholars argue that Taiwan is only a starting point, and that after Taiwan, China might turn its sights on the Philippines or Vietnam. I find this perspective puzzling. Historically, China hasn’t expanded in that way, and its current behavior doesn’t support such claims. For example, China and Vietnam conduct joint naval patrols in Haiphong Bay despite their disputes.

I don’t see evidence that China’s growing power has led to an expansion of its ambitions. Instead, I see a country focused on advancing long-standing historical interests with improved means, not a fundamentally new or aggressive agenda. There’s no indication that China’s strategy involves moving from Taiwan to broader regional conquests.

Jordan Schneider: Well I’ll grant you that. But here’s the rub — Taiwan, in a Westphalian sense, is as close to being a state as you can get. There are treaties between the U.S. and Japan, the U.S. and South Korea, the U.S. and the Philippines, and the Philippines and Vietnam. While you might say that these countries understand they need to coexist with China, you don’t see politicians in Japan, for instance, campaigning to abandon their treaty with the U.S.

Even if these treaties suddenly disappeared under a Trump presidency, the world has largely decided it’s not acceptable to invade and take over states. Since 1945, there have been many terrible conflicts, but most have been civil wars or adjacent to civil wars. Ukraine is an exception, and it’s triggered a dramatic global response. Countries worldwide, including South Korea, are supplying artillery shells to Ukraine because they don’t want to live in a world where big countries are allowed to take over smaller countries.

What do you make of this? What is Taiwan supposed to do?

David C. Kang: You are absolutely correct. This is exactly why the Taiwan issue is so challenging, and in some ways, Taiwan is a perfect encapsulation of the problems that arise when applying the European IR model globally.

If we weren’t living in a Westphalian world, Taiwan’s status would be very easy to figure out.

Taiwan is a contentious issue only because we have decided that the sole type of entity deserving of legitimacy, recognition, and a seat at the table is the nation-state.

That is a uniquely rigid way of thinking about the world. Historically, even in Europe, there were kingdoms, principalities, duchies, and so on. In Asia, there were nomadic kingdoms, centralized Confucian states, and other forms of governance. If we weren’t so fixated on Westphalian norms, Taiwan could be its own thing. But that’s not the world we live in.

The easiest solution of the Taiwan issue would be to forgo Westphalian thinking in this instance, and let Taiwan be its own, distinct type of entity. But that’s not going to happen because that’s not the world we live in.

The global system today creates an incompatibility that’s difficult to resolve. If there were an easy answer, we’d have found it by now.

I have two main points about Taiwan.

The idea that China is preparing to invade Taiwan is more prevalent in the U.S. than in China. In Washington, D.C., the amount of money being spent on war-gaming simulations is staggering. Every few months, there’s a new prediction about when China will invade — 2027 is a popular date right now.

But I don’t think Chinese leaders are approaching this the way Americans think they are. From everything I’ve read, the CCP and Xi Jinping reserve the right to use force because they view Taiwan as part of China. However, it’s not framed as an imminent invasion. The strategy so far has been to kick the can down the road, and that strategy has been remarkably successful.

I do not understand why we are trying to change the status quo in Taiwan. The U.S. has maintained a policy of acknowledging China’s claim to Taiwan without endorsing it. China, in turn, says it reserves the right to use force but hasn’t acted on it. Meanwhile, Taiwan has its own flag, it’s own currency, and it’s own government. Taiwan has flourished in this environment, transitioning from a brutal authoritarian regime under the KMT to a thriving democracy. The island has grown wealthy, and China has grown wealthy too. The status quo is imperfect, but it works.

In terms of alliances, you are right that Asian countries are not abandoning their ties to the U.S. But let’s consider what happened when Pelosi visited Taiwan a couple of years ago. Within a week, every major Asian country, including ASEAN members like Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines, publicly reaffirmed the One China policy. The only exception was South Korea, but even there, not a single official government official met her at the airport. President Yoon Suk-yeol wouldn’t meet with Pelosi during her visit. He claimed he was on vacation and wouldn’t pick up her calls.

I was at the Yongsan Presidential Office in South Korea last year, and I spoke with a senior national security advisor. When I asked about South Korea’s stance on the One China policy, he said their position has remained unchanged since normalizing relations with China in 1992. They adhere to the One China policy but won’t just reaffirm it every time China demands them to. The South Korean defense minister stated that he doesn’t want U.S. forces stationed on Korean soil to get involved in the event of a Taiwan conflict.

If there is a war over Taiwan, I suspect many Asian countries would slowly back away and avoid direct involvement.

Jordan Schneider: What’s fascinating is that the One China policy is almost like a modern version of an imperial-era common understanding. It’s not perfect and nobody is super happy, but it prevents war. China agrees to leave Taiwan alone, and Taiwan agrees to keep quiet and not embarrass China.

The concern is whether this delicate arrangement — “fudging it,” so to speak — will be enough going forward. CCP’s actions in autonomous regions, as well as in Hong Kong, raise doubts. Hong Kong was supposed to be the model for an enlightened, semi-autonomous relationship with Beijing, but that experiment has clearly failed. You saw what Mao did to Tibet.

Would you like to expand on the parallels you see between the One China policy and Korean diplomats sending “be nice” reminders to Beijing?

David C. Kang: The main distinction would be what’s internal and what’s external. We don’t have to like it and we don’t even necessarily have to agree with it, but China considers issues with Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong to be internal. That’s very different from their relations with Vietnam or Korea.

Jordan Schneider: To clarify, Korea wasn’t viewed as internal in the year 1100, correct?

David C. Kang: Korea was not internal. It had formal tribute relations with China, however. The Koryo dynasty was never conquered by the Mongols. They suffered unbelievably, but they never gave in. The king survived. He had to keep moving around and stuff like that. They finally settled their relations with the Yuan dynasty when Kublai Khan decided he was going to adopt Chinese methods of doing things, and then they entered into tribute relations. The Koreans had to give princesses, but Korea remained as an independent country.

Jordan Schneider: What I’m saying is, if Taiwan could establish a kind of tributary relationship with China — where they play nice on the international stage, they send some symbolic gifts, and call their Olympic team “Chinese Taipei” — then that’s a compromise Taiwan and Taiwan’s allies would be open to accepting. But if China wants Taiwan to be another Xinjiang or Tibet, then things get a lot more complicated.

David C. Kang: Absolutely. This gets to the heart of the issue — what is internal, what is external, and how Taiwan fits into that dynamic. Taiwan is an unusual case because its status is unclear and doesn’t fit neatly into traditional categories.

China claims it annexed Taiwan in 1684 and argues that it has always been part of China. Others dispute this. What is clear, though, is that no other country claims Taiwan. Koreans don’t think it’s Korean. Filipinos and Vietnamese don’t claim it. Even Japan, which once ruled Taiwan, no longer stakes a claim. Taiwan may not definitively belong to China, but no one else is saying it belongs to them either. This ambiguity is one reason Taiwan is often treated as a Chinese issue within a broader civilizational framework.

Another important point is that Taiwan’s indigenous peoples historically never developed the kind of centralized government capable of engaging in formal diplomatic relations with China or other states. This contrasts with the Ryukyu Kingdom (Okinawa), which maintained formal tribute relationships with China, Japan, and Korea before being annexed by Japan in 1879. Similarly, Hawaii had a recognized monarchy before its annexation by the United States in 1898. While independence movements exist in Okinawa and Hawaii, they’re largely symbolic and seen as politically unviable.

Taiwan’s situation is different due to its unique geopolitical context. Its de facto independence exists more because of larger political factors than because of any historical claim to sovereignty. That’s the reality of international politics—it’s not necessarily about fairness but about the broader strategic situation.

Ilari Mäkelä: You have a great line in your book, “Despite decades of Western predictions to the contrary, it is by now widely admitted that East Asian states are not forming a balancing coalition against China out of fear of its rise.”

There are two ways to interpret that. One is that these countries don’t feel the need to balance against China. You also point out that military spending as a percentage of GDP has steadily declined across East and Southeast Asia, regardless of whether a country is a U.S. ally or not.

The other interpretation is that the U.S. acts as a kind of “gray eminence,” enabling this reduction in military spending. Many in the U.S. argue that it’s only because of American protection and military presence that these countries feel secure enough to avoid an arms race.

David C. Kang: That’s a long-standing argument, but I’m not entirely convinced. Let me explain why.

First, there’s an assumption that countries like Korea and Japan should naturally ally against China, given shared interests. But that hasn’t happened. For decades, I’ve heard arguments like, “Come on, Koreans, don’t you realize Japan is your friend and China is your enemy?” But those arguments don’t resonate in the region. Koreans don’t love China, but they don’t hate Japan as much as some think either.

The region doesn’t operate according to the neat balancing logic of realist international relations theory. American policymakers often push Asian countries to “balance” against China, but many simply don’t see the situation that way.

If U.S. protection were the primary reason for regional stability, we’d expect to see clear differences in behavior between U.S. allies like the Philippines, and non-allies like Vietnam or Malaysia. But we don’t.

Second, there’s the question of U.S. commitment. In recent discussions, I’ve been asked what China might be learning from the Ukraine war. My response is that Taiwan should also be paying attention to how the U.S. has responded.

Despite strong rhetoric, the U.S. has been very cautious about directly engaging in a war with a nuclear-armed superpower. Ukraine is on Russia’s doorstep, and while the U.S. has provided significant support, it has avoided direct confrontation. This raises an important question — would the U.S. really go to war over Taiwan, or even the Philippines?

This is a critical concern for Asian countries. They constantly assess whether they can truly rely on the U.S. in a crisis. Despite what alliance treaties might say on paper, the answer is far from certain.

Ilari Mäkelä: The final question I always ask my guests is, how has your research shaped your outlook on humanity?

David C. Kang: The biggest way my research has changed the way I view the world —and my outlook on humanity — is that the more I’ve delved into scholarship, whether it’s my earlier work on economic growth, political economy, and corruption in East Asia, or my decades of work on history, I’ve come to realize just how central values and beliefs are to human behavior.

People are far more motivated by what they value and believe in than by a simple cost-benefit analysis. I see this repeatedly, whether at the individual level or in the way nations act.

As scholars and social scientists, we often lean on cost-benefit frameworks because they’re more comfortable or measurable. But in my experience, values and beliefs are far more influential in driving decisions, shaping both individual actions and international relations.

Jordan Schneider: By the way, would you like to recommend any good books about the Imjin War or other topics we’ve discussed today?

David C. Kang: Yes! We already mentioned Liam Kelley’s Beyond The Bronze Pillars: Envoy Poetry And The Sino-Vietnamese Relationship, which is absolutely eye-opening. It explores how Vietnam historically viewed its relationship with China.

Sixiang Wang’s Boundless Winds of Empire: Rhetoric and Ritual in Early Chosŏn Diplomacy with Ming China is another excellent book. That’s the one you quoted earlier. It just came out, and it’s fantastic.

I also recommend Yuhua Wang’s The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development. While I don’t agree with everything in it, it’s an insightful materialist perspective on state formation in China, focusing on how China centralized and grew.

For a more classic take, Bin Wong’s China Transformed: Historical Change and the Limits of European Experience is a standout. It compares the Chinese and European paths of growth over the centuries and highlights the unique aspects of China’s development.

On the Imjin War specifically, there isn’t a definitive English-language book that comes to mind. [From the comments: Kenneth M. Swope’s A Dragon’s Head and a Serpent’s Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598. (University of Oklahoma Press, 2009).] Elizabeth Berry’s biography of Hideyoshi is excellent. It covers his life overall, and includes the Imjin War, although that isn’t the book’s exclusive focus.

Jordan Schneider: Since we just mentioned Hawaii, I’d like to shout out Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands by Gavan Daws.

It’s one of the most beautifully written books I’ve ever read. I’ve probably gone through ten books on Hawaii, and this one stands out far and away. It does an incredible job of telling the story of Hawaii’s transition from a kingdom to becoming part of America.

Editor’s note: for example, the hiragana symbol き ki comes from the Chinese character 去, which is pronounced qù in modern Mandarin and khì in the Hokkien language of Southeastern China. The visual similarity is clear, but the phonetic connection is only apparent from the Hokkien pronunciation of the character.

"On the Imjin War specifically, there isn’t a definitive English-language book that comes to mind." Kenneth M. Swope A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598. (University of Oklahoma Press, 2009).

Like other commenters (and perhaps the hosts of the podcast), I'm pretty skeptical that China's historic hegemony is the result of non-Western cultural norms. To me it still seems downstream from power dynamics: when one state massively overpowers all the others, everyone else has to live with them. Perhaps the real issue is over-application of power-balancing theory by IR wonks.

However I do agree with the point about empires committing suicide instead of being murdered. Both China and the US' leadership seems to be in a race to do just that. China has perhaps the more severe structural issues, but I think over the past month the US has taken the lead.