Autocracy and Stagnation: How Imperial Exams Shaped China's Destiny

Keju's role in slowing technological development

Yasheng Huang 黄亚生 is the author of one of the decade’s greatest books about China — The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline. It’s a rich book, a product of a career of reflections, with each page delivering something novel and provocative.

In this first half of our two-part interview, we discuss…

How the imperial examination system (known as keju) shaped Chinese governance, culture, and society,

Why autocratic Chinese dynasties benefitted from a meritocratic bureaucracy,

Statistical methods for analyzing social mobility in imperial China,

How the keju system survived the Mongol conquest,

What the tradeoffs in the imperial exam system can teach us about the future economic prospects of China and Taiwan.

Co-hosting today is Ilari Mäkelä, host of the On Humans podcast.

Listen on Apple Podcasts:

Listen on Spotify:

Frictionless Autocracy

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with Emperor Wanli 萬曆帝 and Henry VIII. How would you contrast these two figures?

Yasheng Huang: They lived close to each other in historical terms, but in dramatically different political systems. The basic difference was that Wanli didn’t have to deal with anybody to do what he wanted. Specifically, he wanted to nominate his third son as his successor, but that was being pushed back by Confucian bureaucrats. He was dealing with opposition, but he only encountered opposition from the bureaucrats on this one issue and this one issue alone.

Henry VIII, on the other hand, had to deal with peer opposition. The biggest peer was the Pope. He had to get permission to divorce his wife to marry Anne Boleyn, whereas Wanli didn’t need permission at all. He only encountered opposition from the bureaucrats on this one issue. Otherwise, he was completely free. That was the point of the story. The difference between the East and the West was laid down long ago, and that historical imprinting has some bearing on the differences between China and the West.

Jordan Schneider: We’ve got Henry VIII, who wants to marry this woman and has to fight tooth and nail against all these other forces in the system. Whereas Emperor Wanli, basically, no one was going to stage a coup against him. No one was going to really push back. There were no other power centers, and even all these ministers who kept giving him trouble, at the end of the day, he held all the cards when it came to his relationship with them. With that image, I’d like to fly all the way back to pre-Sui China. Let’s do the same contrast between what was going on in the Han and post-Han era and what you saw in the Roman Empire.

Yasheng Huang: Many early Western civilizations placed value on violence, warfare, and battle, and many of their luminary leaders came from military backgrounds.

When you look at early Chinese history, certainly there was violence and warfare.

But there was also something I didn’t quite see in the history of the West — emphasis on assessing human capital through artificially created metrics, essentially exams, rather than promoting or demoting people according to their record on the battlefield.

According to historical records, that goes way back, before the Sui dynasty in the 6th century. The Sui dynasty essentially institutionalized that method. For a bit of historical background, the Qin dynasty unified China in 221 BCE, and China remained united until 220 CE, when it collapsed into multiple kingdoms. Warfare broke out among them. The Sui reunified China from this fractured collection of kingdoms into a unified country, similar to what Qin did in 221 BCE. But one big difference was that the Sui dynasty invented the exam system, called keju 科舉 in Chinese, that kept China unified.

The Qin dynasty unified China but didn’t succeed in keeping the country unified. Whereas if you look at the era after the Sui dynasty, most of the time, China was united. There were periods when China fell into disunity — notably in the 20th century — but most of the time, China was unified. This was a dramatic shift from disunity to unification, which I attribute to the keju system.

The Roman Empire, on the other hand, kept its empire together mostly through military conquest, with some political governance methods as well. But they didn’t succeed in unifying the empire for long. It collapsed, and Europe never went back to the Roman Empire, despite efforts by many generals. Europe today basically reflects the fragmented situation that happened after the Roman Empire collapsed. That was the enduring difference between China and Europe.

Ilari Mäkelä: Bringing that moment of Sui as a kind of threshold, watershed moment in China’s history is really eye-opening. It raises a lot of new questions and gives a lot of new answers. Before we delve deeper into that, let’s take one more look at the time before it. There’s this period of fragmentation that you already mentioned between the collapse of the Han before the reunification, which you call the Han-Sui interregnum. You tongue-in-cheek called that China’s European moment. In what sense was this period, which most people don’t even really have a good word for, China’s European moment?

Yasheng Huang: The Han-Sui interregnum is an era that most historians don’t pay much attention to. The Han dynasty lasted 400 years, and the Tang dynasty is another glorious dynasty, as is the Song dynasty. This period in between is often overlooked. I call it a European moment in the sense that, it’s similar to the post-Roman Empire era in terms of fragmentation, political freedom, ideological freedom, warfare, constant changes of government, the importance of nobility, and the mobility of human capital.

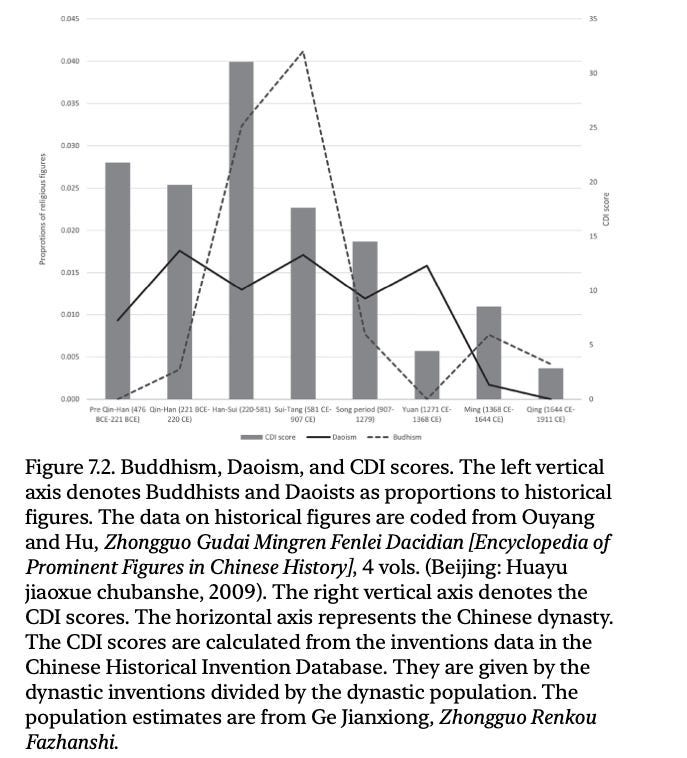

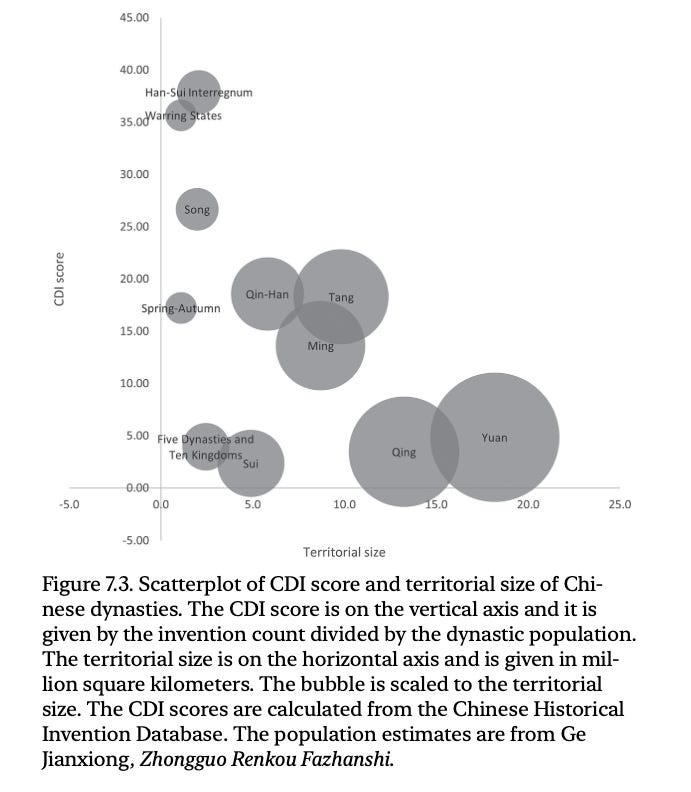

Crucially, that was the peak of Chinese technological inventiveness. It was also the peak of Chinese humanistic creativity. If you look at the measures of technological development and humanistic creativity, they coincided during that era, and I don’t think it happened by accident.

Ilari Mäkelä: Could you talk a little bit about how those measures work? I think we were both quite impressed. There are some really fascinating graphs, but can you give a little more of an idea? What exactly are you measuring when you have technological development or humanistic development?

Yasheng Huang: That work is really standing on the shoulders of a giant — in this case, Joseph Needham, Professor of Cambridge University. He, his students, and colleagues compiled 27 volumes on Chinese science and civilization. The documentation was done by him and his team. There’s still a Needham Institute at Cambridge University today. Needham himself died in 1995.

What we did, and that was a collaborative project with Chinese academics, was spend six years digitizing this impressive collection of information. Needham, even though he himself was a scientist, never really looked at his material statistically or used a data approach to analyze the information he collected. I wrote a whole book on the Needham question. Together with my Chinese collaborators, we were responsible for creating this database. It took us six years with some 40 research assistants.

What we did sounds simple, but the process was incredibly difficult and complex. Essentially, we tallied up the number of inventions that Joseph Needham compiled and then divided that number by population. Chinese historians have come up with very complete estimates of the Chinese population, dynasty by dynasty. That’s another work done before us — there’s no way we could do that ourselves. Our contribution is digitization, analyzing the information using a data approach.

Amazingly, that data approach reveals insights that I don’t think we are able to get just by reading historical materials and telling historical stories. One of the fundamental findings from our work is that a peak happened during this European moment. There’s absolutely no way you can get that insight by just reading Needham’s 27 volumes.

We also have a measure of historical development in terms of humanistic creation. One was actually published more recently by a group of scientists using digital textual data to analyze the textual richness of Chinese historical documents. It turns out this Han-Sui interregnum had the highest level of textual richness, measured by how many writers refer to the text created during that era, compared with the text created in other eras.

It’s quite amazing. When I went into this, sometimes I get pushback by people saying that I’m ideological, that I had my mind made up before I began. I’m not a historian. The Han-Sui interregnum, the only thing I knew about that era was from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which I read as a primary school student. I really knew nothing about that era. How could I have had a prior view to be so precise? It really just came from data.

That’s another thing I want to do in this book. I don’t invoke values or even theories. I let data speak. I let facts speak, and we follow data to their letter and to their spirit. I really want to push back against this view that automatically you have a Western ideological view because you emphasize diversity, freedom, and competition, and that somehow is ideology rather than fact. I’m telling that story from China’s own history. I do hope that I win some hearts from people who have an automatic immunity to Western ideas.

Jordan Schneider: One of the more interesting and challenging parts of your book is that people gravitate to stories and narratives. Your book, said with a lot of love, is very thoughtful and provocative, but there is a lot more drama contained in more narrative histories where you’re looking at personalities.

When you push back on a lot of the scholarship that has been trying to look at these questions of China’s technological rise and fall and what keeps it unified or not, you bring some interesting datasets to the field. I’m curious about methods for understanding China. Why do you think there has been so much overweighting on these sorts of narratives that you can kind of assert, particularly when it regards this question? Why did it take until 2023 for someone to write your book?

Yasheng Huang: As a professor at MIT, I do have some belief in the ability of systematic approaches and methods to provide us with insights. My book also has personalities and narrative accounts. But there’s a difference between just telling narrative accounts and using stories and accounts to illustrate insights. I’m trying to do the latter rather than the former because I’m not a historian.

To me, these are incredibly interesting things in and of themselves. But my ultimate interest is to reveal general principles and regularities in history, society, economy, and politics. Among China scholars, at least among the older generation, that has not been the primary motivation for going into China scholarship. Their interest is in history itself, in telling stories about Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping. Those are really important things. I’m not denying any value in doing that, but as a more scientifically oriented scholar, my interest is in revealing regularities and insights, rather than those historical details in and of themselves.

Younger scholars are doing more and more of that systematic research. But let me also add that the constraint in academia now is that the stories, arguments, and insights that we emphasize in these very systematic journals are getting smaller and smaller. It’s actually easy to be systematic and small. It is not that easy to be systematic and big. At least I try to be systematic and big. Maybe some people will say I’m not systematic enough, and other people may say I’m not big enough. At least those are my intentions, to do both of these things.

Ilari Mäkelä: I think it would be difficult to find people who say that you’re not big enough. It’s a wonderful big arc of history that you’re offering. But let’s continue the arc. At the moment, we see that during the Han-Sui interregnum, we have this Chinese European moment. But as you mentioned earlier, there are already seeds of using exams or a history of using exams on a level that we don’t really see in the West. Long story short, we get the Sui dynasty. We get a big, very systematic examination system where a lot of political power, although the emperor has the ultimate say, a lot of the middle management is more and more taken in via this standardized examination system. And that ends up being kind of a blessing and a curse for China. Is that a fair, quick summary of what’s happening next in your story?

Yasheng Huang: That’s very fair. Interestingly, a lot of the liberal intellectuals in China criticize the keju system because they think it’s really bad. They argue it’s just memorization, nothing else — conservative and even reactionary. I agree with that. But on the other hand, I also see that the keju system contributed tremendously to Chinese human capital development and literacy.

Let me just make sure that your audience knows this — it was only open to the male segment of the population, it was never open to the female segment. But there was a spillover effect. Mothers were mainly responsible for bringing up their boys and educating them. The preparation for keju started very early, at three or four years old. Thus, mothers had to be able to read and write.

It’s not an accident that in terms of 20th-century economic miracles, many of them happened in East Asia with the legacy of keju and its human capital. One of the things that keju did was homogenize human capital. We can come back to the bad side of that. But let me just emphasize the positive side.

When you work in a factory, when you work in manufacturing, when you try to scale your EVs, when you try to scale your solar panels, if you have inconsistent human capital from one worker to another worker, you cannot scale these technologies. Going back to the shirts that we wear, going back to the shoes that we wear, it’s not just high tech, even this low tech — anything that you have to do at scale requires consistency, requires human capital consistency. Keju, I’m not saying it’s the only thing, but it contributed critically to the formation of that human capital consistency.

Ilari Mäkelä: Before we go to the bad part, could I ask one more thing about the good part? One of the things that I was really surprised when reading your book is how much you suggest that there was genuine social mobility created by the keju. Because the really short story often told is that in Europe, you have to be an aristocrat to have political power. In China, anyone can take this exam. And I was always skeptical, thinking, "Yeah, okay. But no farmer is actually going to be able to train their son for this exam and actually succeed." It’s a nice story to tell, but actually, the outcome is the same thing. The aristocratic kids get a good education. The farmers don’t have a chance. And you suggested I’ve been a bit too bleak. Right?

Yasheng Huang: The historians who study keju use the term "social mobility." I may have used that term as well in my book, but more precisely, it is political mobility. Social mobility implies that you are a farmer, and you go up in social ranks, economic ranks. You can become an entrepreneur, you can become a professor, become a government official. That’s social mobility because it’s social rather than just narrowly political.

In the keju case, it’s really just political. You become an official, you become a bureaucrat. In that sense, it is limiting your range of mobility to one thing only: the imperial bureaucracy. You didn’t go into commerce, you didn’t go into universities, you didn’t go into other things like political opposition, for example. You didn’t go into the church. So, yes, there is that incredible mobility. You could be a farmer, and then you took the exam, you succeeded, and then you became an official. So in that sense, it’s not social mobility, it is political mobility.

Ilari Mäkelä: But there was genuine political mobility.

Yasheng Huang: Oh, absolutely.

Ilari Mäkelä: How would you convince a skeptic of that?

Yasheng Huang: Very easily. Again, going back to our earlier conversation about data, this is not something you can just use stories to illustrate. You kind of have to use statistics and data. An earlier historian, Ping-ti Ho 何炳棣 who really pioneered research on the keju showed that it was meritocratic. There are later historians who study keju, and they say, “Oh, so-and-so came from a prominent family, and he also succeeded. He got promoted.” But the problem with that is, how do you know it is the prominent family part that contributed to his mobility? Maybe he was extremely smart.

I’m not saying that the second view is necessarily wrong, but all I’m saying is that just telling that story itself is not convincing enough to make your point. In my work with Clair Yang from the University of Washington, we ran statistical tests to determine the effect of family backgrounds on exam performance. Whether or not you came from a rich family, whether or not you came from a politically prominent family, your father was a government official, your grandfather was a government official. Statistically, if that background influenced your exam score, we should be able to see it. We should be able to detect that effect in the statistical results we generate.

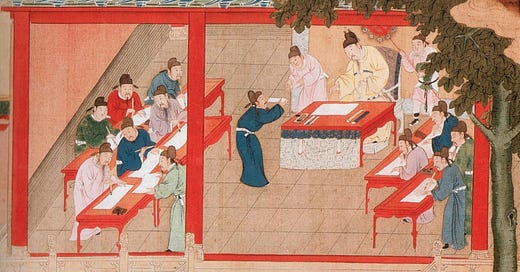

Indeed, because you had three rounds, in the first two rounds that were anonymized, we didn’t see any effect of family backgrounds on exam scores. That’s quite impressive — going back to the 6th century, 7th century, 9th century, and 13th centuries — that your backgrounds didn’t influence your exam scores. That means they had a pretty good system. It’s called anonymization. China actually invented the double-blind system. The examiner didn’t know who the examinee was. The examinee didn’t know who the examiner was. That was really incredible. That was an incredible invention, and China should get credit for it. To me, that’s more convincing evidence that the keju system was truly meritocratic.

Jordan Schneider: This is a nice transition to talk about court politics dynamics. There is one fascinating point that you brought up in looking at educational attainment and family background — at the very richest level, there was actually a bit of a negative correlation, because the emperor is smart, and they know that they don’t want to have a chief minister who actually has money, connections, and land.

This comes to the sense that you made very clear of there just not being other power centers. How did the emperor’s ability to literally handpick the top echelon jinshi 進士 class shape China for so many centuries?

Yasheng Huang: In the first two rounds of the civil service exams, family backgrounds didn’t affect the exam scores. However, in the final round, known as the palace exam, backgrounds were known to the examiner. This round included both written and oral components, with the emperor presiding as the chief examiner.

Surprisingly, candidates from wealthy families performed worse during this round. This is counterintuitive, especially when compared to contemporary educational systems where socioeconomic background often correlates positively with educational access and performance. Our research revealed a negative correlation in imperial China.

We attribute this to the emperor’s reluctance to appoint officials from independent power bases to central government positions. The final round selected the most important officials for the imperial court - those who would design future keju examinations, advise the government, and have direct access to the emperor. This system effectively marginalized the nobility and successful merchants.

This contrasts sharply with European royal families, which were interconnected and shared power. In China, the emperor maintained absolute dominance through a vertical system. Even imperial concubines were chosen from peasant backgrounds in remote areas, deliberately excluding those from prominent families.

The system’s cleverness in maintaining power is remarkable, though it’s unclear who specifically devised it. It likely evolved as collective wisdom over time.

Jordan Schneider: You also examined how emperors dealt with top ministers they disagreed with. Could you elaborate on this and its benefits to the system?

Yasheng Huang: Our research revealed an interesting pattern in Chinese imperial history. In earlier periods, ministers who disagreed with the emperor were often executed. However, after the implementation of the keju system, ministers typically resigned voluntarily when conflicts arose.

This shift can be attributed to changes in the nature of disagreements. Earlier bureaucrats and ministers might have posed fundamental threats to the emperor’s rule, necessitating their physical elimination to prevent potential coups. In contrast, later bureaucrats, shaped by the keju system, accepted the overall legitimacy of the imperial system even if they disagreed on specific policies.

Clair Yang and I are writing a book about China’s political evolution, using precise data to show that the frequency of coups decreased significantly after the keju system was established. The system served as an ideological tool to homogenize human capital in terms of both skills and ideology.

For instance, during the Wanli era, when the emperor abstained from ruling, no one considered overthrowing him despite his neglect of duties. This acceptance of the system’s legitimacy allowed for a more peaceful resolution of disagreements, where ministers could simply resign rather than be eliminated.

Ilari Mäkelä: Your work draws an interesting connection between the "frictionless autocracy" of Chinese emperors and the examination system. The keju system effectively centralized human capital and political mobility, preventing the emergence of alternative power centers. However, this raises questions about technological innovation.

You’ve presented data showing that Chinese inventions were more prevalent before the Sui dynasty, with a subsequent decrease. You’ve also noted a correlation between the prevalence of Buddhism and innovativeness, suggesting that intellectual diversity fosters innovation.

However, the Song dynasty seems to contradict this pattern. It’s often regarded as one of China’s most innovative periods, producing or refining many significant inventions. Shen Kuo 沈括, a Song dynasty polymath, is legendary perhaps to the point of da Vinci status. To many people’s eyes, it’s the Song dynasty that represents China’s european moment. How does this fit into your overarching argument?

Yasheng Huang: The Song dynasty does present a challenge to our thesis, and we address this in detail in our forthcoming book from Princeton University Press on the history of Chinese technology.

While the Song dynasty was indeed innovative, inventing three of the four great inventions (gunpowder, printing, and the compass), it’s important to note that it was still a unified empire trending toward a single ideology, unlike the European situation.

In our current research, we’ve developed a measure to assess the importance of inventions. Even when weighting major inventions more heavily, the Han-Sui interregnum still emerges as the most inventive period. This period saw significant advancements in pure mathematics and other important inventions that are less well-known than the "four great inventions."

Ilari Mäkelä: We haven’t discussed the role of commerce as a potential power base. Some scholars, like Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, emphasize the importance of commercial power as a competitor to political power in England’s industrialization. How does commerce fit into the story of frictionless autocracy in China? Could the commercial activity in the Song dynasty explain its innovative streak?

Yasheng Huang: Commerce can impact both technology and politics. There’s likely a connection between vibrant commerce and technological innovation, which may have contributed to the Song dynasty’s achievements. However, commerce is just one of many factors.

In the context of the Western Industrial Revolution, commerce played a role within a broader framework of political and intellectual freedom. Commerce alone is insufficient to launch an industrial revolution.

Chinese commerce always operated in a restricted environment, similar to how Jack Ma’s commercial empire prospered but remained constrained by political factors. This restricted environment could foster technology to a point, but not to the extent of launching an industrial revolution.

Regarding politics, evidence increasingly shows that commerce alone doesn’t change political structures.

The Song dynasty had vibrant commerce but remained autocratic. In fact, it invented one of the most restrictive ideologies in Chinese philosophy — neo-Confucianism — while Buddhism declined.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting to consider how this tradition persisted even after interactions with border countries and foreign conquests. One of the more dramatic things you said at the very beginning, like one of the downsides of not valorizing generals and generalship is that you kind of lose more wars. The Han people did a lot of that over the past 2000 years. You probably wouldn’t expect nomadic horse tribes to all of a sudden decide that eight-legged essays 八股文 were the best way to run their country.

How did invaders like the Mongols and Manchus, who weren’t initially invested in Confucian ideals, end up adopting and perpetuating these systems?

Yasheng Huang: The reverse takeover of China by the keju system is a fascinating piece of history. The Mongols initially had no such system in their culture or civilization, as they were primarily focused on warfare. However, at some point, they recognized its usefulness for ruling their vast empire.

The Yuan dynasty, presiding over an enormous territory, needed a large number of capable bureaucrats and administrators. Keju provided the means to acquire this human capital and ensure consistency across the empire. The Mongols not only resurrected keju but also innovated by incorporating the most restrictive ideology into its curriculum.

Cleverly, the Yuan dynasty utilized two Han Chinese inventions, keju and the Neo-Confucianist ideology developed by philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹 during the Song dynasty. They combined these elements to create the most restrictive institution in Chinese history. The narrowing of the curriculum, which began in the Song dynasty, reached its apex under Mongol rule.

The subsequent Ming dynasty, ruled by Han Chinese, adopted the Mongol modifications to keju. Even the Qing dynasty, not ethnically Chinese, quickly recognized keju’s utility. This demonstrates the system’s power as a toolkit for autocratic rule.

Jordan Schneider: Indeed, the key takeaway from this system is the trade-off between scale and dynamism. While having 10,000 bureaucrats well-versed in Confucian texts ensures a level of competence, it may not foster radical innovation or dramatic changes — for better or worse.

This principle extends to imperial succession as well. Primogeniture may not always result in the most capable ruler, but it provides clarity and stability, avoiding the bloodshed often associated with other succession methods, such as those seen in the Ottoman Empire or the Yuan dynasty.

Yasheng Huang: Your observation is excellent. When examining the political history of both East and West, we see that each system developed methods to resolve conflicts. Democracy allows for disagreement within established rules, while autocracy relies on force or indoctrination to quell dissent. Primogeniture is another conflict resolution tool, providing clear succession rules to prevent power struggles.

Wang Li’s proposal to violate primogeniture was potentially dangerous to the regime, prompting pushback from Confucian mandarins who recognized it as undermining a critical rule of succession. The Chinese system adapted by having Confucian scholars educate the heir apparent from an early age, instilling Confucian values and ethics as an additional safeguard.

Ultimately, these systems aim to resolve conflicts, either by relinquishing some control or by consolidating it. China opted for the latter approach.

The Downfall of the Imperial Exam System

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss the late Qing period when the system began to unravel. Increased commerce, exposure to the West, and military defeats led to a growing realization that changes were necessary. New ideologies emerged, such as those that fueled the Taiping Rebellion. By 1905, the keju system was abolished, marking the end of an era. Can you elaborate on this transition and the continuities (or lack thereof) between the imperial tradition and the subsequent Republican era?

Yasheng Huang:

Several factors contributed to this transition.

1. Population growth during the Qing dynasty made the keju system increasingly competitive, as the number of available positions did not increase proportionally.

2. The Qing dynasty, aware that keju favored Han Chinese due to their long history with the system, actually decreased enrollments, exacerbating the competition.

3. Ideological challenges arose. While keju had successfully suppressed Buddhism and Taoism, Christianity proved more difficult to contend with, arriving in China with significant force.

4. Western intrusion further weakened Manchu rule.

The Taiping Rebellion exemplifies the convergence of these factors. Led by Hong Xiuquan 洪秀全 — a failed keju candidate who embraced Christianity — it demonstrated the system’s inability to maintain legitimacy. Although the rebellion was eventually suppressed, it drained government resources, leading to the sale of official positions and further undermining keju’s credibility.

These factors collectively contributed to the collapse of the imperial system and the establishment of the republic.

Ilari Mäkelä: Another significant development was the creation of a modern army to combat the Taiping Rebellion. This led to the emergence of powerful military leaders, such as Yuan Shikai 袁世凯, which contributed to the empire’s downfall. How significant do you consider this aspect of the story to be?

Yasheng Huang: While the military’s growing power was indeed a factor, we shouldn’t overstate its importance. Civilians, not generals, primarily initiated the Republican revolution. It was a revolution driven by ideas and regional rebellions rather than a classic military coup.

The military largely attempted to defend the regime rather than overthrow it. The collapse resulted more from the loss of ideological narrative and the imperial system’s legitimacy. Increasingly, I believe the role of ideas and ideology to be a more significant driver of history than economics or military power alone.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss Chiang Kai-shek, a leader with a unique ideological blend of Christianity, fascism, and Confucianism. What elements do you think he adopted from the imperial tradition, and were there aspects he should have emphasized more?

Yasheng Huang: The Nationalist Party, under Chiang Kai-shek and his son, struggled to balance scale and scope more than their imperial or communist counterparts. They never fully resolved the conflict between Western influences and Chinese autocratic traditions, resulting in an unstable arrangement that allowed for some diversity but lacked a decisive direction.

This lack of resolution led to ad hoc solutions and eventual democratization in Taiwan. Chiang Kai-shek attempted to maintain an autocratic veneer while incorporating some elements of scope and diversity, which is not an ideal combination. Democracies are generally better equipped to productively incorporate heterogeneity.

A similar pattern emerged under Deng Xiaoping in mainland China, but with different outcomes. While Taiwan evolved towards democracy and the institutionalization of scope, China moved in the opposite direction.

Ilari Mäkelä: To clarify for our listeners, when you mention scale and scope, you’re referring to the system’s ability to handle uniformity (scale) versus diversity and heterogeneity (scope). Is that correct?

Yasheng Huang: Exactly. Scale refers to economies of scale, producing millions of identical widgets or maintaining a single party and ideology. Scope encompasses diversity, such as having multiple political parties, liberals, and conservatives in a democracy.

My book explores how China initially grappled with these opposing forces before ultimately favoring scale at the expense of scope and diversity. In contrast, Western countries resolved this tension by embracing scope, creating systems that can manage conflicts while promoting economic development and preserving political and ideological diversity.

Ilari Mäkelä: The keju system seems to be a prime example of favoring scale over scope. You have a compelling line in your book, "Too much autocratic stability is detrimental. This conclusion is not based on Western values and ideology, but on China’s own history."

Yasheng Huang: I aim to convey this message through Chinese history, hoping to persuade people to reconsider their aversion to diversity and competition. China has historically prospered when it allowed for a degree of diversity, both in ancient times and in the contemporary period.

For those concerned with economic growth, development, technology, and science, China should celebrate diversity rather than suppress it. The evidence from China’s own history supports this conclusion.

Subscribe for next week’s edition where we take the story from 1949 up to the present