BalloonTalk: Emergency Edition

Balloon bloodlust, the epic military history of balloons, the fate of US-China relations, and how balloon expertise can help you on Hinge

What on Earth is a Chinese spy balloon doing over the US? To discuss, we have William “Balloon Guy” Kim of The Marathon Initiative, Eric Lofgren of Acquisition Talk, and Gerard DiPippo of CSIS. We dive into:

The epic military history of balloons;

Why it’s surprisingly difficult to shoot down a balloon, and the US-China “balloon gap”;

Whether Secretary of State Blinken should have canceled his trip to China;

How expertise in balloons could improve your dating prospects.

This is a long one (I promise it’s worth it!), so I recommend opening it up in a webpage or in the Substack app.

No Strings Attached

Jordan Schneider: Welcome to perhaps the most important ChinaTalk show of the six years I’ve been doing this.

What the hell just happened?

Gerard DiPippo: It was yesterday that the Pentagon and NORAD announced that there was a balloon that they were tracking from China that was, at the time, over Wyoming or Montana. The bottom line: it caused a diplomatic minor crisis.

First of all, the Chinese government was vague and kind of denied it at first. Eventually the MFA released a statement where they said the “airship” (飞艇), which is what they call the balloon, is in fact Chinese. They claim it was for meteorological purposes — a weather balloon. They said it was drifting because of westerly winds, and that they regret the unintended entry of the airship into US airspace due to force majeure (不可抗力) — a legal concept meaning it’s like an act of God, it’s out of their control — and that they are communicating with the US side to address the issue.

But then, a few hours later, the US government announced that Secretary Blinken would not be flying to Beijing as planned. He was supposed to be wheels up tonight; now the trip is postponed indefinitely. The State Department has not said when or under what conditions they will resume the trip. But they have said that, basically, while they recognize the Chinese side has since regretted it — which is a meaningful statement coming from them — it was still a violation of US sovereignty, and they found it unacceptable and inappropriate for them to go at this time.

Jordan Schneider: I don’t even know where to start. Will, why would a Chinese balloon be over Wyoming?

William Kim: It is possible that they’re telling the truth and it did just malfunction and drift away. But blimps do offer advantages, compared to satellites, in terms of things like intelligence collection. Satellites are very difficult to conceal, and they find predictable orbits. Spy satellites tend to be quite large, so you know when they’re there.

Now, this balloon doesn’t seem to be something that would be easy to hide — we’ve been tracking it so far. But it could offer much more persistence: if you have a balloon that’s there all the time versus a satellite that maybe is overhead just a few times a day. And the US can know, “Hey, we’re not going do anything too secretive while a satellite is overhead” — so there are definitely reasons why they might want to use this balloon for intelligence collection.

Gerard DiPippo: Has the Pentagon or anyone confirmed that it is — or at least the view is that it is — a spy balloon and not a weather balloon? How confident are we of that?

William Kim: All the statements I’ve seen have said “surveillance balloon.” I have not seen anything, at least officially, indicating that there’s ambiguity or that it may be a weather balloon.

Jordan Schneider: In the Chinese statement, it said, “气象等科研” — for scientific as well as other purposes.

William Kim: It also looks rather large compared to weather balloons that I’ve seen. So that’s one thing that makes me a little suspicious of that cover story.

Eric Lofgren: Why is it so hard to take one of these things down? Is there a cost-effective way to bring it down — or why are they leaving it up there?

William Kim: As of now, I don’t think there is. For one thing, these balloons are rather cheap: it depends on the payload, but you could make one under $1 million, or even under $100,000. So if you’re going to shoot a $4.5 million surface-to-air missile at it, you’re not going to have surface-to-air missiles for very long.

But in terms of hitting them — these are not balloons you have at a birthday party where you can just poke it and then it pops. There was an instance where a Canadian weather balloon went rogue, and they had fighter jets shooting at it with 20 mm cannons, and it still took six days before it finally came down.

Jordan Schneider: Could you grab it? How high are they?

William Kim: This one doesn’t appear to be very high. Some of these can go well past 100,000 feet, which is beyond the ceiling of any aircraft.

Eric Lofgren: Even if you wanted to shoot a missile at it, could you target it? How would you target a balloon? It’s not reflecting radar.

William Kim: That’s the thing — the balloons themselves do not actually reflect radar; the payload will. But the problem is the payload is very slow, and these missile guidance systems are designed to hit fast-moving targets, to shoot down missiles or aircraft — and they’re actually designed to ignore chaff, which is what these balloon payloads very well may look like.

So I think it’s an open question how well these surface-to-air missiles would even work if we shot at it. Although, I should clarify: as far as I know, it’s never been tried before.

Jordan Schneider: Well, tell it to me straight: is there a US-China balloon gap — and can I sleep at night until it’s closed?

Gerard DiPippo: The short answer is, “I don’t know” — and the long answer is, “The people who do know probably aren’t going to say.” But I do think there is reason to be concerned that the Chinese clearly have an interest in and are developing this technology. And I think we need to be doing more on our end, both to develop cost-effective counters to this — things like energy weapons that could be used against this — as well as our own capabilities when it comes to high-altitude balloons.

I’m very concerned that the Chinese could potentially use these for not just surveillance but also strikes in the future. During World War II, the Japanese used to send balloons at the United States. To be sure, they killed only six people because they were very inaccurate — but high-altitude balloons can definitely carry payloads large enough for bombs or missiles or something like that. The US Army has a concept for suicide drones launched from balloons.

Carried Away by History

Jordan Schneider: This is a good little transition: Eric, apparently you have balloons in your genes. Give us a little history of America and its interactions with balloon warfare.

Eric Lofgren: It turns out my grandfather worked at Goodyear as a military contractor doing this stuff for the Navy back in the day. So two hours before this podcast, I called my dad: “Give me the lowdown on balloons.” And of course, he knows everything about the military history of balloons.

They were mostly for recon stuff, mainly tethered. They actually started to be used during the Napoleonic Wars — but the first big time they were used was in the Civil War for artillery targeting: they were inflated using coal; it was the first time that they put a person on board one of these airships.

In World War I, they started meeting opposition from powered flight: but these things were using hydrogen at that time — so it was super dangerous for a pilot to get in close and shoot the hydrogen package, because then it would then burst and there would be a big fire.

What Will was talking about — those are using helium, and inert gas won’t ignite. So when you shoot them down, nothing’s going to explode; it will just drift down for a long time.

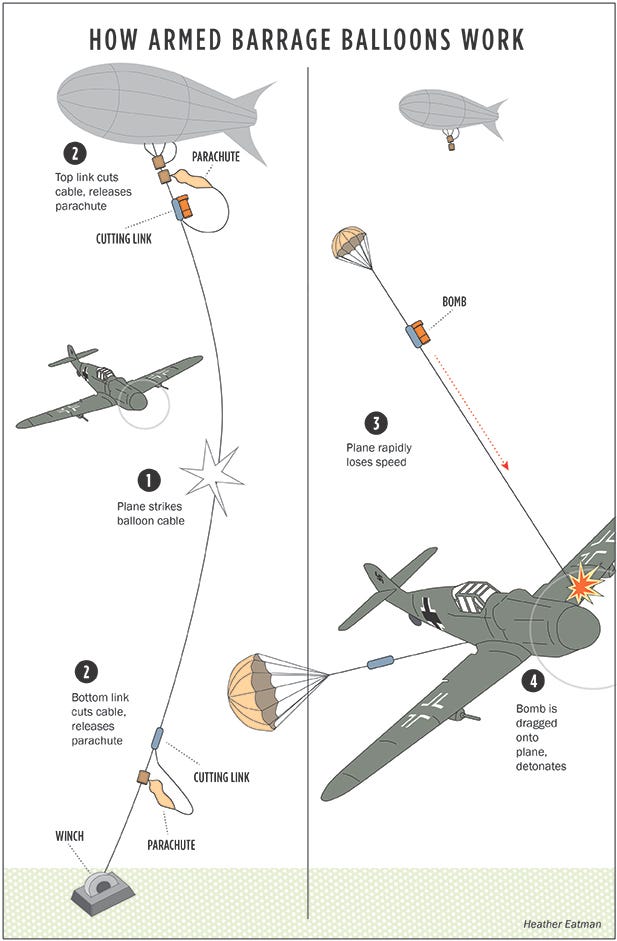

But for the most part, they were used in World War II as barrage balloons: you’d cable them to the ground, and they would prevent bombers from coming over. The Brits had these for the Battle of Britain to foil the Luftwaffe. And when you look at pictures of D-Day, you’ll see all the supply ships out there with a bunch of these barrage balloons. They didn’t do much because the allies killed most of the Luftwaffe fighters and bombers at that time; so they weren’t really attacking the D-Day fleet. But that’s what they were used for.

Jordan Schneider: Eric, explain the barrage balloon concept?

Eric Lofgren: Basically, these balloons go up really high, and you would attach tethers to them and other types of chaff and cables — so when bombers tried to come through, they would be hit with these nets and cables, which would prevent them from hitting ships or hitting London or wherever.

Jordan Schneider: So it’s like catching fish in a net in the sky with balloons?

Eric Lofgren: Pretty much. People were innovative back then!

They were actually used for U-boats, too; they protected convoys. Before nuclear submarines, you would keep a balloon up there — you could have a pretty big payload and have a big radar on there — and it would force the U-boats to say submerged. Otherwise, even if they just had a periscope up, you’d be able to catch them with these balloons, because they had long loiter times. So they used these to degrade the capabilities of Nazi U-boats.

They used them up until 1962 — essentially when the Soviets were introduced with nuclear submarines. That’s the downfall of the age of airship balloons.

Jordan Schneider: I want to stay on the “Japan bombing America with balloons” story.

Eric Lofgren: It was kind of similar to what they had here: you would put incendiaries on these balloons and let the jet streams take them over. They were targeting the Pacific Northwest, hoping to create forest fires. It wasn’t too effective.

Jordan Schneider: I think it happened after the US started bombing the Japanese homeland, right? The context I remember it in: they’re trying to have some kind of propaganda win. And the other interesting wrinkle with this: there was a big media blackout in the US because they didn’t want the story to get out; I think it was highly classified for like decades that the Japanese balloons actually ended up being able to hit US targets.

William Kim: Six people were killed by one of those balloons — it just happened to land on a picnic. They were the only Americans who were killed on continental US soil during the entire war.

Keeping Up With Balloon Science

Gerard DiPippo: How do the Chinese communicate with the balloon? How do they collect the data that it’s collecting? Do they have to physically retrieve it? Is there some satellite uplink?

William Kim: I assume, like a satellite, you could just use radio communication. Google’s Project Loon tested out using laser communication between different balloons — which was a big challenge, but they managed to do it.

Jordan Schneider: Wasn’t there going to be balloon internet at one point?

William Kim: Yes — that’s what Google was doing with Project Loon: they were going to float these balloons up, and they would be able to provide internet. The idea was that they would provide internet to areas that didn’t have cell phone towers already — areas that were, for example, particularly poor or rural.

That program has been shut down, but my understanding is that the technology wasn’t — in fact, the technology is pretty incredible: when you learn what these AI algorithms were able to do in catching the wind; this thing that sailors have been doing for thousands of years, the algorithm figured it out on its own.

But the thing is, for something like that to work, it has to be really, really cheap — and my understanding is they just couldn’t get the price low enough for it to be viable.

Eric Lofgren: It sounds like a poor-man Starlink to a degree. It seems to be working for Ukraine, but maybe they could use this in other denied environments.

William Kim: Totally — at least in the military realm, you don’t need the price to be quite as low. For DoD or something, I think it definitely has a lot of potential.

Jordan Schneider: Will, can you talk a little bit more about the algorithms — is there propulsion on the balloons, and how does machine learning help with that?

William Kim: This is why you don’t see this stuff being used all the time: you send it up, and unless it has some propulsion — and there are challenges with propulsion and using engines at that high an altitude — it goes wherever the wind takes it.

But what has happened recently with AI is that these algorithms can figure out how to adjust the altitude of the balloon to catch the right wind: there will be these winds going in different directions, and you can use that to go or even orbit around one spot for an extended period of time.

I know that in some cases these balloons have been able to stay up there for 300 days.

Eric Lofgren: And they can do that without propulsion?

William Kim: Yes. It’s just a matter of going up and down. You don’t need propellers or anything like that.

Jordan Schneider: But there aren’t weather reports for, say, 50,000 feet versus 60,000 feet — or are there? What are your data?

William Kim: That was one of the challenges with doing it — getting the data. I know that DARPA had a project called ALTA which was using laser sensors to collect data and information about weather patterns.

Eric Lofgren: Will, how much research have you done on this? One thing I’ve always experienced in the DC realm is that I do a little bit of work, and then someone comes to me and treats me like an expert on something — but I’m like, “I’m not an expert on it; I just happened to write one thing.” What is your experience with that?

William Kim: I definitely feel the same way: a lot of my knowledge is coming from these two papers that I had in my original thread, which are written by Air Force officers back in the 2000s. And the rest is just media reporting — after reading those, I got into the media reporting of Project Loon and the other things that were going on in the commercial sector.

I used to just go on the internet and Google this stuff for a while — and I guess I was the only person in the national-security space doing this. I always felt like this was something that was a bigger deal than people were talking about. Everyone wanted to talk about hypersonics or autonomous drones — and I’m like, “Hey! Balloons are important.” And I think until now I’ve gotten these very blank stares from people.

So yes: full disclosure, I’m not an aerospace engineer or anything. I’ve never professionally worked on any of these projects, so keep that in mind.

Jordan Schneider: I’m looking forward to the day when you’re managing a $5 billion balloon budget.

I want to come back to this “balloon versus satellite” capability question, because it seems as though balloons have a lot going for them. Are people biased because they’ve seen Up and they think it’s silly, versus satellites which just seem cooler? Do you have a theory of why balloons don’t get more love?

William Kim: I think part of it might just be that, if your whole job revolves around satellites, you wouldn’t necessarily be too big on this kind of thing coming around. There’s a much more entrenched interest in satellites, especially now that we have the Space Force, whose reason for existence is satellites.

One interesting thing I’ve noted is the service which, in my view, has been doing the most work on this is actually the Army, not the Air Force; that might be because they don’t necessarily have the same institutional bias toward satellites.

But I’d also point out that this is a very new thing — and so far, a lot of the people working on this have been thinking of it for commercial purposes, like providing internet. I might just be weird to look at this like, “Hey — this could allow us to kill people more effectively.”

Eric Lofgren: Well, the Army has the JLENS. I did a cost estimate on the JLENS program — which is an aerostat, a balloon that sits above a base to do cruise-missile defense.

And then one day it got loose from Aberdeen and wreaked havoc into Pennsylvania — because it’s tethered, so the tether just kept being dragged along, and you saw these pictures of it taking out poles and all this stuff, and all these people lost power. And then they were just like, “We’re going to shut down the project.” And I think that was the end of balloons.

But the Army was looking at it from a different perspective — that’s why I like having multiple services. Are you going to be advocating that maybe we need some balloon programs going on? What other types of things is the military doing?

William Kim: I believe the Fiscal Year 2023 budget had about $27 million — which is chump change for the Pentagon, but still much larger than it was before (when it was in the single-digit millions). So there is work being done on this.

I think JLENS was definitely a big thing: anytime I break this up to people who are in the know, they’re like, “But JLENS…” — and I’m like, “Yeah … but this isn’t tethered, so it’s different!”

The other thing to keep in mind is that balloons are not completely replacing satellites anytime soon. I don’t think we could just get rid of the Space Force. For one thing — as we’ve seen with the political response here — there’s just a difference in how people react politically to a balloon in their airspace versus spy satellites going overhead every day.

Gerard DiPippo: So does the US use similar balloons against China, and does China do this frequently — or is this a rare occurrence? Do we know?

William Kim: I’ve seen reporting that says this is perhaps a pretty frequent occurrence from China. This is the first time that I’ve really dove into the news — and in fact, a lot of people have argued that, say, UFO military sightings were most likely Chinese balloons. So I don’t think this is that new — it’s just that this time was a lot more noticeable: people could look up and take pictures of it.

In terms of what the US does, I know there are experiments being done — that’s what my original Twitter thread was talking about — and there’s conceptual work. But in terms of any fielded capability, I am not aware of anything that the US military has done.

Eric Lofgren: Well, thinking about the “Tic Tac” and a balloon — I just doubt that aviators are messing that up. Which UAPs — unidentified aerial phenomena — are you saying might be balloons?

William Kim: There was an article in The War Zone talking about how some of the infrared images might actually be balloons. And some of the reports which say, “They are flying supersonic without making a sonic boom” — that could potentially be electronic-warfare packages on them.

This Balloon is Different

Gerard DiPippo: If this has happened before, why is this one getting all this press? Did it get too low or something? Why now?

William Kim: For one thing, the balloon is very big — and that’s what surprised me when I saw photos: you can make these packages much smaller, and I’m not sure why they didn’t. If you compare it to, say, WorldView-3, this payload seems rather large, and it seems to be flying rather low.

I wouldn’t say it’s an overreaction in the sense that the demonstration of this capability is absolutely something to worry about. We have to think about operating under much more persistent PLA ISR than perhaps we’re used to. In my view, we don’t have a very good cost-effective counter to ISR capabilities yet. And we also have to consider whether they can do strikes at ranges that previously would have been unthinkable.

Gerard DiPippo: But this balloon is probably not an armed balloon, right? It’s just surveillance.

William Kim: It’s probably not armed — but then again, NASA had a balloon that could carry up to 8,000 pounds to an altitude above 100,000 feet.

One of the articles that got me into this wasn’t even talking about them for surveillance — it suggested using them as close air-support platforms: sticking a bunch of them over Iraq and Afghanistan so soldiers could just call in bombs whenever they needed. And unlike a plane, they can stay up there much longer. So I think kinetic use is definitely something we should be thinking about.

Gerard DiPippo: And evidently they’re hard to shoot down.

William Kim: So far, yes. I think energy weapons should probably provide a solution there, but we might have some work cut out for us.

Jordan Schneider: For the uninitiated, Will, what is an energy weapon?

William Kim: Sci-fi lasers, microwaves: microwaves would fry the electronics; and with lasers you could heat up and destroy the balloon itself. So far they’ve been relatively short-range, used for things like defense against small drones. I think laser or microwave weapons specifically designed to destroy — or at least capable of destroying — these high-altitude balloons deserve more attention.

Eric Lofgren: Epirus has a microwave thing for which they got a $66 million contract from the Army — apparently they can knock out hundreds of small UASs [unmanned aircraft systems] with that thing.

The directed energy one is funny: a few years ago, they put a laser on a C-130 and popped a balloon from altitude. People were joking about: “Oh, you popped a balloon — who cares?” Well, maybe there’s some utility to that!

William Kim: It’s weird being “the balloon guy,” because like I said, I don’t really think I’m a subject-matter expert — but I realized, “Almost nobody else in the national-security space has even thought about this.”

So I hope that the attention helps us develop these capabilities — beyond JLENS and tethered things, and to more advanced, free-floating designs using AI.

Maybe the solution is the laser on the C-130 — but whatever it is, we have to counter it; we have to have this capability ourselves. So I hope that this starts a conversation, and that people smarter and more powerful than I do more on this.

Jordan Schneider: Eric, I was curious: once China tested the hypersonics, what did that do to the DC conversation around hypersonics — and what might this balloon saga do for Will’s dreams of a massive balloon investment plus-up?

Eric Lofgren: Certainly policy people and defense people are envious — if they have a shiny new toy, we want it, too.

But it did get me thinking, “Is this thing really that survivable?” Because you look at certain missions, like air target moving indicator: we will have a sortie of six or more F-35s — and you need a tanker on station just to keep them forward-deployed — so we can see what’s in the air, say, whether there are some J-20s coming forward. That’s a lot of money — maybe $40,000 an hour — to keep multiple F-35s up there just to be sensing up forward.

If you could put balloons up there: very low cost, very survivable, same EW [electronic warfare] and sensing packages on them — why not? How many more missions can this thing take forward? Because today we’re burning tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars every hour just to do something with high-end equipment when we just don’t need to burn out the engines and airframes of F35s. It seems as though it’s worth some analysis.

Jordan Schneider: Will, this may or may not increase the salience of balloons in the national-security conversation — but one thing it certainly already has done is improve your dating prospects. You recently tweeted out a Hinge response from a long-dead match:

William Kim: People say dating in DC sucks, but I think this is a good counterargument.

Blinken’s China Trip Up In the Air

Jordan Schneider: I don’t think this is the same as putting nukes on Cuba. So what do you think just happened? And can we talk through a little bit of your balloon bloodlust? Why did you want to blow this thing up so bad?

Next up, we get into Gerard’s balloon bloodlust and what this all means for the future of US-China relations.