Biden’s Final Export Control Salvo Misfires

Of scalpels and Swiss cheese. “The dumbest thing you could do is compromise and build your house in the middle of the street.”

Commerce released its much-anticipated chip export-control updates yesterday. To discuss, I was joined by Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis and Greg Allen from CSIS.

We were not impressed. To explain why, we get into:

What’s in the new controls: high bandwidth memory, FDPR, and the Entity List.

How key assumptions in Biden’s approach to export controls limited their ultimate impact.

How China’s stockpiling spree may have already rendered these new rules partially obsolete, and what policymakers can do about that going forward.

The law-enforcement approach vs. the counterintelligence approach, and whether export controls should be a foreign-policy tool or simply a law-enforcement activity.

How the new chip controls are like removing puzzle pieces just one at a time — and why that’s exactly what China wants to slowly but surely self-indigenize.

The “America First” rationale for export controls and domestic chip production.

Why the Democrats’ regulatory design philosophy was lured away by the promise of complexity — and what the Trump administration could do differently going forward.

Click this link to listen to the show on your favorite podcast app.

First, two disclaimers: Most at BIS and within the administration are well-intentioned, understand the stakes, and have worked incredibly hard these past four years to help America compete in chips and AI. We don’t mean to question anyone’s integrity — but at ChinaTalk, we call it like we see it. Also, we recorded this yesterday the same day the regs were released, and given their complexity our takes are inevitably provisional.

Second, a job post. ChinaTalk is hiring for a dedicated China AI lab analyst. Chinese fluency and a technical background are required. Apply here!

And third, a call for donations. ChinaTalk is teaming up the Substack community and GiveDirectly to raise money for households in rural Rwanda. The link to give is here. Every donation made before midnight today will be doubled through GiveDirectly’s matching fund.

When Regs Meet Reality

Jordan Schneider: First, why care about any of this? A four step logic chain.

The US is in strategic competition with China;

Semiconductors and AI applications will shape the contours of the 21st century;

Among AI’s three components — data, algorithms, and hardware — hardware is the area where liberal democracies have the best chance of developing a long-term competitive advantage over China;

This advantage can be maintained only through aggressive government intervention.

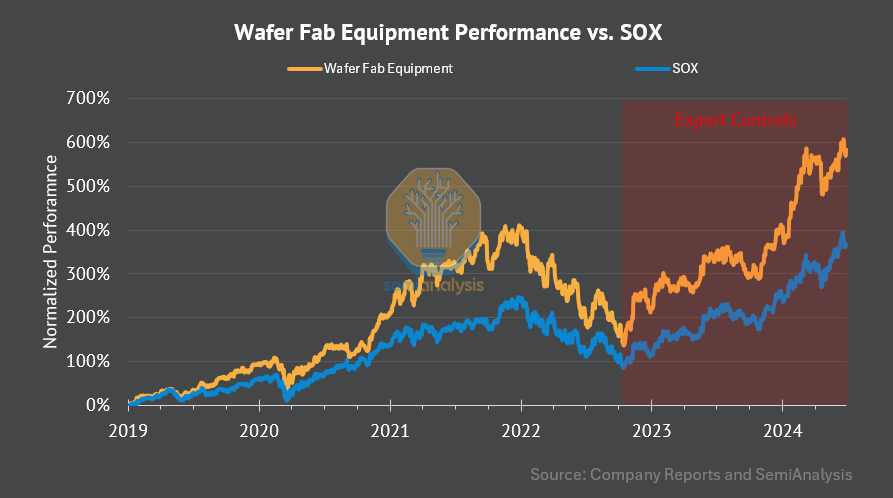

The October 2022 export controls were excellent — prescient in addressing the competition’s stakes before ChatGPT’s release, and creative in deploying new authorities in an area where the US government had to quickly develop expertise. The October 2023 update, while delayed, effectively addressed major loopholes, particularly regarding GPU exports.

However, over the past 18 months, it has become increasingly clear that semiconductor export controls aren’t achieving their intended goal of slowing Chinese progress in advanced semiconductor development. The new rules released today I can’t give anything higher than a C+. There are real steps forward in these regs, but their delayed release was deeply harmful, and there are far too many counterproductive concessions to industry.

While many government tasks are genuinely difficult — educating a nation, pushing the frontiers of science, achieving peace in the Middle East — crafting effective export controls is relatively straightforward. The US, through its engineering excellence and position as the arsenal of democracy, has tremendous leverage over global technological flows and its treaty allies. Congress has given the Commerce Department statutory power, and the Treasury has provided the framework. The process is simple: write regulations, enforce them with billion-dollar fines, and you create a powerful global compliance regime.

Companies and nations are about to stomach far more stringent measures under a Trump administration to maintain good relations with America than what Biden could have implemented under a more expansive vision of semiconductor export controls. However, modern Democrats seem reluctant to fully commit to aggressive action. The result is an overly complex policy that trips over itself and misses the bigger picture.

Greg Allen: These export controls present a mixed picture. They’re undeniably stronger than the October 2023 update, but two crucial factors affect their impact: timing and implementation. The delayed release is significant, particularly considering Chinese stockpiling. While the controls are stronger, major gaps remain in the overall framework.

The Biden administration’s high-level strategic vision for semiconductor export controls makes sense conceptually. However, there’s a disconnect between this vision and its implementation across these 200-plus pages of policy. Chinese customers and their suppliers have demonstrated infinite capacity to find legal loopholes, working continuously, while our government manages only one update per year. This mismatch in pace of legal innovation is problematic.

Jordan Schneider: What was the strategic conception that limited the Biden administration’s speed and aggressiveness? What were their key assumptions?

Greg Allen: Two main factors created boundaries: the complexity of these controls, and the stakeholder dynamics. These regulations are massive and incredibly complex.

This complexity stems from negotiations involving three main stakeholder groups:

The US interagency process (Commerce, State Department, Defense Department, intelligence community, White House)

US industry, which maintains dialogue with all these organizations

Other governments, particularly Japan and the Netherlands, who have their own semiconductor manufacturing equipment export controls

The controls must be multilateral to prevent other countries from simply filling the gap left by US restrictions. Beyond Japan and the Netherlands, other crucial players include Taiwan, Korea, and various European countries. This extensive consultation process results in 200-plus pages of regulations that everyone can “agree” to, but requires a full year between updates.

Meanwhile, China rapidly identifies every loophole and stockpiles materials for future needs. While we have significant advantages in strategic technology competition with China, the question becomes how effectively we utilize our advantages compared to how China leverages theirs.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s examine the premise that Japanese and Dutch cooperation is essential. From a legal-technical perspective, it’s not. A more unilateral approach could implement the Foreign Direct Product Rule, stating that any company using American technology selling restricted equipment would violate US law, facing billions in fines and potential stock exchange delisting.

Unlike the satellite industry situation in the 1990s, these technologies are so complex that companies couldn’t simply engineer around American contributions to sell to Chinese fabs. The Biden administration understood this potential leverage but seemed unwilling to forcefully impose it on Japanese and Dutch partners, largely because their central foreign policy ethos emphasized cooperative international relations after the Trump era.

This reluctance to use maximum leverage led to extended negotiations resulting in complex, 200-page regulations that will enrich export control lawyers. If we can identify numerous billion-dollar loopholes within hours of release, imagine what lawyers will find in a month.

Greg Allen: The Foreign Direct Product Rule and its extraterritorial application is crucial here. While other countries may lack similar authority — as demonstrated when Japanese companies circumvented restrictions on semiconductor chemical sales to South Korea — this new package significantly expands the rule’s scope.

Let me break down this extraordinary expansion of legal authority. The traditional Foreign Direct Product Rule might prevent, for example, German companies from simply repainting American missiles and selling them to restricted countries. The 2020 Huawei controls expanded this to cover chips made using US equipment, even if manufactured in Taiwan.

The December 2 rule goes further: if your chip equipment contains any chips made using US machines, the Foreign Direct Product Rule applies. This effectively covers almost every machine globally, including Chinese ones, since virtually all computer chips involve US technology in their production.

Notably, Japan and the Netherlands received exemptions when shipping from their territories, essentially as recognition for adopting their own export controls. However, the rule still applies to their companies’ operations in other locations, such as Japanese company Tokyo Electron’s shipments from Malaysia.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s examine the other assumption — the perceived need to accommodate industry demands. Based on the rule’s writing, timelines, and recent reporting, it’s clear that American semiconductor manufacturing companies’ concerns influenced the decision-making process. The final rule takes seriously corporate fears about these rules doing lasting damage to American SME.

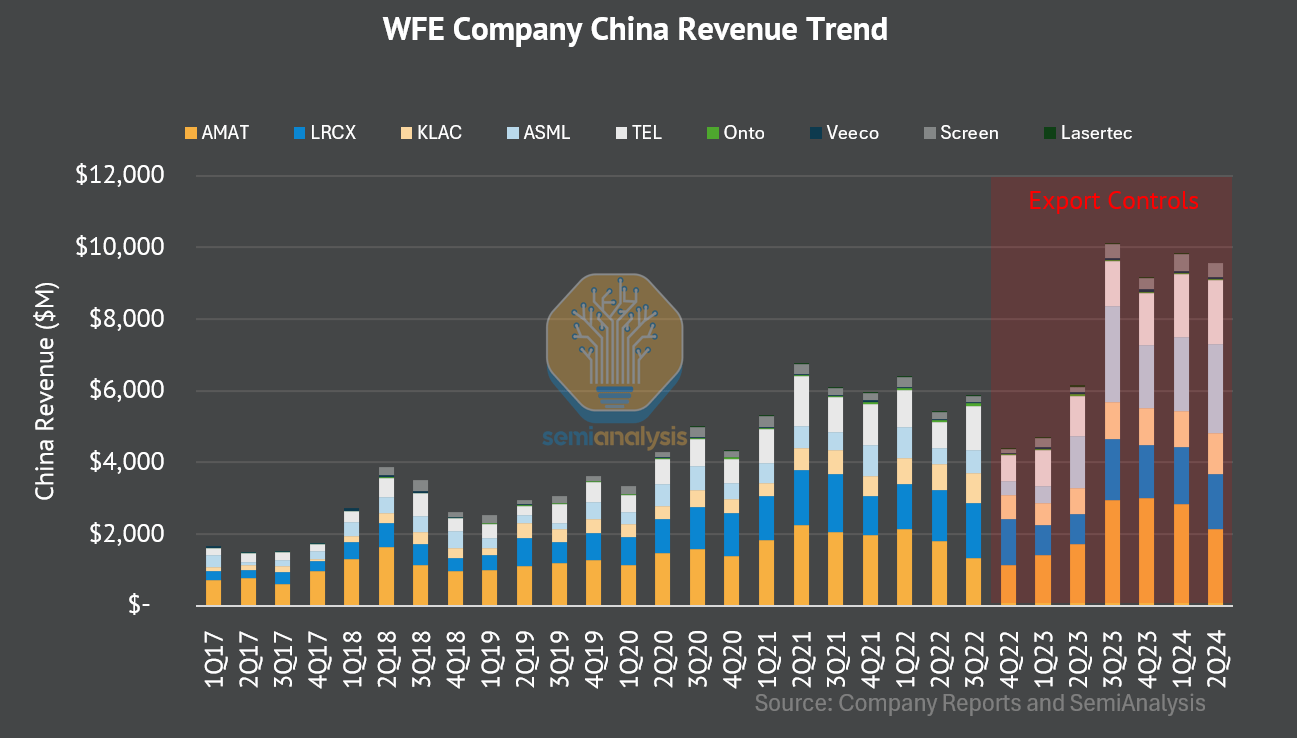

Dylan, could you discuss semiconductor equipment manufacturing firms’ sales and market performance since October 2022?

Dylan Patel: When the October 2022 regulations were announced, everyone panicked initially — the first reading suggested everything would be blocked. Then it became clear these regulations were full of holes. This triggered a surge in Chinese purchasing, as they realized they could still get what they needed despite nominal restrictions.

China’s share of purchases from major equipment companies jumped from around 30% to the high 40s — peaking at 49% for some companies. After the October 2023 update, business dipped briefly but quickly rebounded as new loopholes emerged. This pattern appears to be repeating.

In some cases, there won’t be any business decrease. Applied Materials’s largest Chinese customer faces virtually no restrictions and will continue increasing purchases. They’ll spend more on memory equipment than the largest American memory company. These companies will maintain their profitable Chinese business because lobbyists ensured loopholes remained — or new ones emerged.

The stocks have risen significantly, and their China revenue is up massively. Another key development — their production outside the US has soared, whether it’s Lam Research in Malaysia or Applied Materials and KLA in Singapore. These restrictions have driven massive expansion of non-US production.

Greg Allen: The export restrictions have impacted the composition of semiconductor manufacturing equipment demand. China is buying more legacy equipment since advanced node chip manufacturing faces restrictions. Much production that would have occurred in China has moved elsewhere.

ASML’s executives have stated their demand forecast isn’t based on China’s actions but on overall chip demand — like how many chips the next Apple smartphone needs. Whether those chips are made in China, Taiwan, or Korea, they’ll be produced because end-market demand exists, and ASML holds a near-monopoly.

Regarding China’s growing demand, I expect it to decrease in the next year or two, regardless of export controls. They’ve pulled forward significant demand through stockpiling — buying three to five years’ worth of equipment. ASML reports their Chinese customers struggle to install equipment as fast as they’re acquiring it, anticipating future export controls. That 49% quarter reflected purchases intended for 2025-2027.

Dylan Patel: Previous rounds of Chinese restrictions have shown they maintain a high percentage of revenue longer than expected. While they’re purchasing beyond current plans, money continues flowing because strategic priorities and purchasing waves persist for years — even when market-based demand would suggest three years’ worth should suffice.

What’s in the Regs

Greg Allen: This regulation has three major components.

First, after two years of restricting AI chip sales on the logic side, it now addresses memory — specifically, high-bandwidth memory chips.

Second, it significantly expands the Foreign Direct Product Rule’s application to semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Third, it adds numerous Chinese companies to the Entity List — identified by the US government as shell companies for Huawei, SMIC, and others.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with high-bandwidth memory (HBM). What is it, and why is it important?

Dylan Patel: Looking at an AI chip like Nvidia H100 or Google TPU, roughly half the manufacturing cost — and it’s trending higher — comes from high-bandwidth memory. While TSMC remains the linchpin for making the logic, the logic chip itself is less valuable on a total cost basis than the high-bandwidth memory.

We’ve restricted AI chips to China to varying degrees. Though some still slip through smuggling, China faces decent restrictions on AI chips or receives weaker special versions. However, high-bandwidth memory hasn’t been restricted at all. This memory, alongside logic, represents the two linchpins of AI chip manufacturing.

ChinaTalk listeners have heard much about SMIC and advanced logic, but less about China’s high-bandwidth memory. Their high-bandwidth memory manufacturing ecosystem lags behind their advanced logic development — it’s received less focus. Korean companies have readily sold HBM to China.

A major market story involves Samsung’s struggles — they still can’t sell HBM memory to Nvidia because their quality falls below SK hynix and Micron. Despite being the world’s largest memory maker, Samsung isn’t supplying the highest-end Nvidia products. Their organizational leader issued an apology note so drastic that people joked someone might have hanged themselves in the parking lot.

Samsung’s largest HBM customer today is China, representing about 30% of their HBM sales. They sell some to Google TPU, Nvidia, and Amazon, but most ends up in Huawei Ascend products and upcoming AI products. These AI chips continue domestic manufacturing despite lacking HBM production capacity.

Some puzzling aspects remain. CXMT, Applied Materials’ largest equipment customer, has an HBM manufacturing subsidiary about a year from production — is not entity-listed. Similarly, Huawei’s HBM manufacturing subsidiary isn’t listed. Despite equipment controls potentially catching shipments to them, they avoided Entity Listing. Nevertheless, this necessary regulation helps prevent China from acquiring AI chips.

Jordan Schneider: Oddly, this doesn’t take effect for a month. We’ll see planes loaded with high-bandwidth memory flying to China over the holidays.

Dylan Patel: This actually reflects the need to communicate with other parties. When you ban chip manufacturing immediately, you must address existing inventory. Nvidia, Google, and Amazon don’t want HBM2E anymore. When Nvidia faced restrictions on selling AI chips, they could redirect sales elsewhere during the chip shortage. With HBM, Nvidia has no interest — they’re focused on HBM3e for upcoming product launches.

Greg Allen: Multiple types of high-bandwidth memory exist: HBM2 (since 2017), HBM2E, HBM3E, HBM4, and soon HBM5. The rule still permits HBM2 sales to China, though with intense end-user checks and new regulations. You can sell HBM2 to Chinese customers directly, but not through distributors, and not to those planning to use it in AI chips. While HBM has other applications, AI drives the primary demand.

This approach considers Samsung’s desperate position in the HBM market while attempting to control distribution through end-user verification. Chinese companies might achieve large-scale HBM2 manufacturing within a year. The strategy mirrors our logic chip approach — banning advanced GPUs while allowing older, lower-performing versions, despite the strategy’s potential failures.

Jordan Schneider: This raises another strategic question — whether end-use controls limiting specific fabs or customers represent a reasonable policy approach compared to nationwide controls found in other components of current and past regulations. What’s your take on this strategy’s efficacy?

Greg Allen: The government’s opinion on this strategy appears in the document. They acknowledge that while end-use based controls have had some effect, circumvention has occurred. Consider this — if selling equipment to companies engaged in advanced chip production in China was already illegal based on end-use criteria, why add these companies on an end-user basis?

The Commerce Department and selling industry effectively self-assessed their inadequate effectiveness in preventing targeted sales through end-use controls. This doesn’t mean the controls had no effect — SMIC can’t produce as many 7-nanometer chips as they’d like due to equipment constraints — but the impact could have been stronger.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s move to part two, FDPR.

Greg Allen: After discussing restrictions on logic and memory chips themselves, we must consider manufacturing equipment. There’s no strategic value in restricting chip sales if China can produce them domestically. While China has a domestic equipment industry, it remains small globally and technologically inferior to US, Dutch, and Japanese state-of-the-art capabilities.

This control significantly expands the Foreign Direct Product Rule’s application to semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Let me explain through simplified legalese: the basic version prevents scenarios like selling missiles to Germany, who might repaint them and resell to Russia. The rule states that regardless of modifications, it remains an American missile under US law.

In 2020, the Trump administration expanded this interpretation to include chips made by TSMC using American-built semiconductor manufacturing equipment. This effectively cut Huawei off from advanced smartphone processors. The new control goes further: if your chip manufacturing equipment contains any chip made using US equipment, the rule applies. This encompasses virtually all semiconductor manufacturing equipment globally, including Chinese-made equipment.

The rule has two triggering mechanisms.

First, advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Essentially all equipment needed in the EUV era — including lithography, deposition, etch, and metrology equivalents — regardless of origin, cannot be sold to China. This addresses previous loopholes where US manufacturers moved production abroad. The restriction affects foreign providers, too. Tokyo Electron, for instance, faces the rule when shipping from Malaysia, while shipments from Japan or the Netherlands fall under local versions of the rule.

The second trigger involves end-user and end-use controls. Customers engaged in advanced semiconductor manufacturing or identified as risks for diversion to Huawei or SMIC face restrictions.

This represents a massive regulatory change that might affect semiconductor manufacturing equipment stocks.

Dylan Patel: I see two main workarounds.

First, the diplomatic exception for Japan and Netherlands — they’ll implement their own versions months later, as they did after the October 7 restrictions.

Second, the rule apparently doesn’t cover subsystems sold to China. It covers only equipment. Companies like UltraClean — which makes cleaning equipment for Applied Materials and Lam Research — seem unaffected unless selling to entity-listed companies.

Greg Allen: The rule significantly expands the list of Chinese semiconductor manufacturing equipment producers on the Entity List, including major component producers. Since October 2022, US companies cannot assist Chinese semiconductor manufacturing equipment providers. Strategically, if we don’t want China having chips, we shouldn’t provide equipment, components, or intellectual property for their production.

Dylan Patel: Companies like Ultra Clean and MKS Instruments apparently can still sell subsystems to China, except to Entity Listed companies like NAURA 北方华创, China’s largest equipment maker. This represents a potential loophole in the current regulations.

Jordan Schneider: Greg, let’s move to part three — Entity List.

Greg Allen: The third part represents a massive expansion of Chinese entities on the Entity List, primarily focusing on fabs identified as potential diversion risks to Huawei or SMIC. These are shell companies that were missed in the previous Entity List update.

The expansion includes chip fabs and companies manufacturing equipment or equipment components in China. In defense of the US government’s position — while end-use based controls might be sufficient for US oversight, the Dutch and Japanese lack equally effective implementation capabilities. Adding companies to the Entity List clarifies our expectations to allies regarding rule implementation.

This also helps Bureau of Industry and Security license reviewers. When a Chinese firm’s lawyer provides a sworn statement denying advanced chip manufacturing involvement, finding that company on the Entity List immediately invalidates such claims.

Jordan Schneider: Dylan, were there any notable fabs or companies excluded?

Dylan Patel: There are three major players in China today: SMIC (China’s logic manufacturing champion), CXMT (China’s memory champion), and Huawei, which handles both aspects independently. Through their subsidiaries, Huawei ranks as either the third or fourth largest equipment purchaser globally.

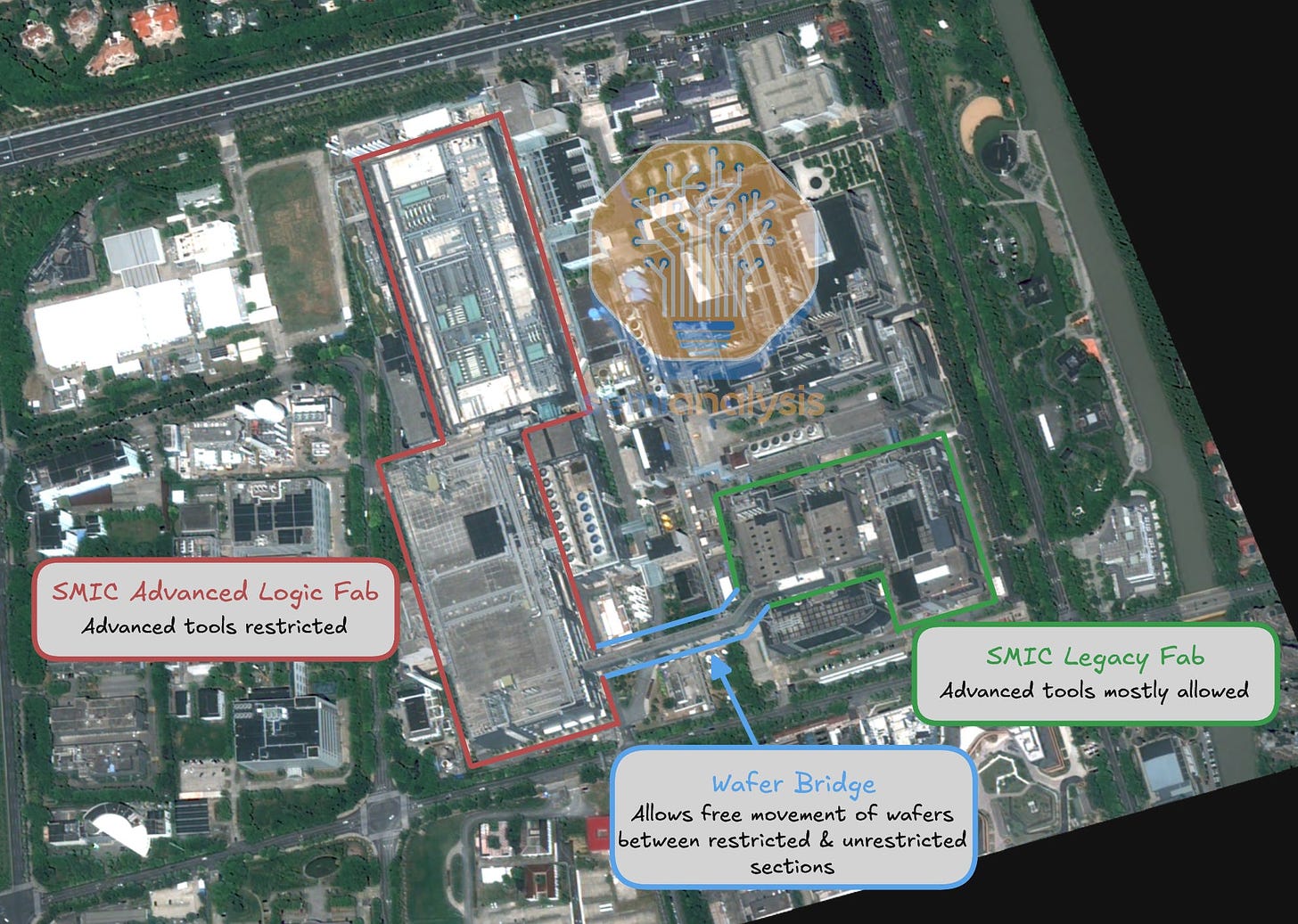

Regarding SMIC, the changes were minimal. They adjusted the licensing policy for their original Beijing fab to “presumption of denial,” but their Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai facilities remained largely untouched. For instance, the wafer bridge issue we discussed in our Fab Whack-A-Mole report — where one fab is Entity Listed while another isn’t — wasn’t fully addressed.

Greg Allen: They did add language about physical connections between fabs, specifically addressing wafer bridges — though it applies only when equipment can be definitively leveraged across facilities. They’re attempting to address geographic proximity issues, like situations where you can’t sell to SMIC but can sell to a supposedly different company across the street. The effectiveness remains to be seen, but they’ve acknowledged these concerns.

Dylan Patel: Even with potential wafer bridge restrictions, their new fabs established since 2022 haven’t faced restrictions beyond end-use controls. SMIC was initially added to the Entity List in 2020, but these new facilities operate without additional constraints because they claim to develop only 28-nanometer technology and above.

Greg Allen: All of that is in in air quotes…

Dylan Patel: Exactly. The insufficient impact on SMIC represents a major issue. Regarding CXMT, which produces memory and DRAM for HBM and standard applications: they’re China’s largest equipment purchaser by individual entity and Applied Materials’s biggest Chinese customer. And they weren’t added to any Entity List, despite clear violations.

The government initially set an 18-nanometer half-pitch restriction for DRAM in 2022. When CXMT’s 17-nanometer technology violated this limit, they simply relabeled it as 18.5-nanometer. The new regulations now include specific physical metrics and memory cell sizes to prevent such ambiguity.

Additionally, CXMT presented research at a US technical conference showing vertical gate-all-around transistor development below the 18-nanometer half-pitch restriction. Despite publicly demonstrating violations of both the transistor and pitch regulations, no action was taken. Their HBM subsidiary also remains unlisted. Tool restrictions might affect them, but that’s uncertain.

Greg Allen: It’s baffling. We’re telling China they can’t buy foreign HBM anymore, yet we’ve exempted their national champion in HBM. The reasoning is unclear.

Jordan Schneider: This raises questions about plausible deniability. Regarding Western and foreign equipment manufacturers — how aware are they of what their machines are getting used for?

Dylan Patel: They definitely understand but avoid written documentation. Equipment servicing generates substantial data logs, particularly for EUV tools which require constant connectivity. Manufacturing involves two-way communication — companies seek advice and assistance from equipment makers. While manufacturers could theoretically ignore the data, they’re aware of actual usage patterns.

There’s an unverified rumor about a senior US government official potentially joining an equipment company’s board…the regulations significantly impact equipment makers’ competitors but barely affect Nvidia’s Chinese competitors. The disparity between naming 140 equipment companies versus few fabs raises questions.

Greg Allen: Regarding foreign companies’ perspectives, Japanese firms often misinterpret US objectives. A Murata executive suggested developing parallel supply chains for US-led and China-led economic blocs. This misses the point — our goal isn’t supply chain separation but strategic impact on China’s AI industry.

The Biden administration’s communication of strategic rationale has been imperfect. The AI National Security Memorandum finally clarified the focus on frontier AI and maintaining long-term competitive advantage — but this message needs consistent reinforcement in foreign capitals.

Jordan Schneider: I don’t blame them for not understanding! Companies have a fiduciary responsibility to prioritize profit over American long-term national competitiveness. The solution mirrors the Treasury Department’s approach in the 2000s and 2010s: substantial fines for violations. The lack of major enforcement actions against Japanese and American firms undermines regulatory effectiveness.

The absence of CXMT from the Entity List, despite partial coverage by various restrictions, exemplifies this problem. Besides small-scale smuggling cases and unresolved investigations into companies like Applied, there haven’t been meaningful penalties for pushing regulatory boundaries. Companies continue selling billions in equipment while strategic objectives remain unfulfilled.

Dylan Patel: There was one last carveout that reveals the current strategy of BIS and the Commerce Department. The question is, “Why aren’t all Huawei chip production facilities on the Entity List?” Many remain unlisted.

According to the Financial Times:

Asked how many fabrication plants exist that are not on the list, a second US official would say only that the controls were focused on advanced chip production. People familiar with the situation said there had been an intense debate inside the administration over how to tackle Huawei. One person said some of the Huawei plants were still not operational, so it was unclear if they would be for advanced chips.

This implies they won’t put facilities on the Entity List until they produce advanced chips — which fundamentally misunderstands how fabs work. You purchase the equipment first, set up manufacturing, then produce chips. By the time you’re producing, most equipment is already in place.

Take TSMC, for example. They’re not buying equipment in Arizona for 5nm/4nm anymore. While they’re still purchasing some 3nm equipment, most of their purchases for next year target 2nm production, even though those chips won’t emerge until 2026.

Following this logic, if TSMC were Chinese, we wouldn’t ban them until 2026 when their 2nm chips appear in iPhones — long after they’ve acquired all the necessary equipment in 2025. This same approach applies to Huawei entities, considering more than half remain unlisted.

Greg Allen: This highlights a crucial divide in export-control implementation.

Consider this analogy:

The law enforcement approach: for example, a US citizen accused of spying for China remains innocent until proven guilty in court, maintaining all citizen rights.

The counterintelligence approach: someone merely suspected of being a Chinese spy can lose their security clearance immediately. They don’t wait for definitive proof because, by then, the damage to national security would be done.

BIS currently operates exclusively from the law enforcement mindset — for both good and bad reasons. They treat Huawei fabs as innocent until proven guilty, assuming legacy chip production until shown otherwise. However, waiting for proof means potentially compromising national security and undermining policy effectiveness.

The fundamental question becomes: Are export controls a foreign policy tool for achieving strategic outcomes, or simply a law enforcement activity? We need this mindset shift, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s be clear about the capacity of the law enforcement approach: it only took a TechInsights teardown to discover that TSMC had been manufacturing chips for Huawei. This reveals the limitations of US intelligence community and law enforcement’s ability to pursue that approach.

Greg Allen: This isn’t about the intelligence community’s ability to help; it’s about their willingness. Declassified CIA documents from the 1970s and 1980s show remarkable work assisting export control enforcement. Their Cold War efforts were impressive.

Fast forward to 2024 — where is the intelligence community now? Why was Gina Raimondo blindsided during her China trip by news of the new Huawei phone? Such revelations should come from our intelligence services, not from China. The question isn’t about capability — we know they can perform extraordinarily when motivated — but whether they’re even trying.

Okay, Trump — Your Turn

Jordan Schneider: So we have new regulations with significant gaps, and a new president arriving in six weeks. What should Trump and his team do on chips? And what do you think they will do?

Paid subscribers get access to the rest of our conversation, which includes:

Dylan’s and Greg’s pitches to incoming Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick.

Why America’s “scalpel approach” to chip controls backfired and what a “shotgun approach” could look like.

How China’s focus on trailing-edge chips and power semiconductors creates vulnerabilities that current controls don’t address.

How Trump’s team might use novel tariff strategies to turn China’s massive chip buildout into “ghost fabs”.