Blown Away: EU Faces Stifling Wind Energy Competition From China

It's not just EVs and solar that can't compete

Ryan Featherston is a Research Associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies Trustee Chair in Chinese Business and Economics.

In a lecture given at Princeton on April 9, European Commission Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager announced that the EU would be opening an inquiry into Chinese suppliers of wind turbines. This inquiry follows an earlier anti-subsidy probe into Chinese electric vehicles. And just weeks after that EV probe began, the European Commission released its European Wind Power Package, a new initiative to provide support for European producers who have struggled amid uncertain demand, increasing input prices, and pressure from competitors in China.

These actions mark a significant milestone in the EU’s reevaluation of its economic relationship with China — a relationship increasingly marked by suspicion and anxiety — and green tech is front of mind for policymakers.

Like EVs, wind brings a certain sense of déjà vu to European industry leaders as they watch Chinese producers embark on the path to internationalization. Vestager said as much in her speech: “We can’t afford to see what happened on solar panels happening again on electric vehicles, wind, or essential chips.” But is it already too late to compete?

Chinese Wind Firms Soar

The success of China’s wind firms was no doubt aided by state support. For the last decade, the government provided generous feed-in tariffs — modeled on policy pioneered in Germany — that incentivized wind-power adoption (see Figure 1). Though the policy was phased out in 2021, by then wind power had already become cost-competitive with fossil fuels within China.

Similarly, wind firms receive generous government grants (see Figure 2) at rates well above the industry average — at least when compared against benchmarks for other industrial sectors, according to the OECD. While average grants received as a share of operating revenue have declined, this is largely due to rapidly expanding revenue; grants themselves have remained relatively stable for major producers like Goldwind 金风科技, Mingyang 明阳智能, and Windey 运达能源. In other words, declining government grants as a share of operating revenue actually indicates that producers are entering a phase of maturation and expansion (see Figure 3).

Early on, China pursued a persistent strategy of technology for market share. For example, Chinese producers benefitted substantially from strict localization requirements that mandated firms source a certain share of relevant components from within China. In 2005, China’s National Development and Reform Commission required that 70% of components be sourced domestically. That policy was later repealed in 2009, after many petitions from foreign suppliers — but by then, Chinese OEMs were firmly established, with local or joint-venture players making up 76% of new installations in 2008.

A particularly vexing fact for EU policymakers and industry leaders alike is that, despite these restrictions, foreign OEMs were still eager to get in on China’s growing market. Gamesa (later purchased by Siemens) established its first factory in 2004. Vestas also invested early in 2006, with its first production facility in China opening in 2006. Now, neither company has significant market share within China’s domestic market.

Another key determinant of Chinese wind producers’ success lies in low input prices, where falling steel and rare-earth prices have made producing in China more affordable. (That’s another reason that direct subsidies don’t capture the universe of support available to Chinese producers.) This form of support is an extension of China’s other industrial policy goals: state support leads to steel and rare-earth overcapacity, creating cost savings for turbine manufacturers. Proximity to inputs at every stage of the supply chain — from steel to advanced rare-earth magnets, a market that China also dominates — creates agglomeration effects for Chinese producers that are hard to replicate, particularly in a global economic environment experiencing increased shipping costs.

Moreover, because wind producers in China have developed in a market with enormous demand alongside fierce competition, the scale of China’s domestic wind installations has far outpaced that of other nations (see Figure 4). In 2023, the European Union installed 14.6 gigawatts of wind capacity, while China installed nearly 76 gigawatts of wind energy. Owing to the sheer scale of China’s market, six of the top-ten suppliers in 2023 were Chinese, with Goldwind and private wind OEM Envision 远景能源 taking the first and second spots (Vestas was third, and Siemens Gamesa was eighth). While global wind installations grew overall in 2023, annual installations in both the EU and North America fell year on year — showing just how central the Chinese market is to the global wind industry.

Given the enormous scale of the Chinese market, Chinese firms are not particularly reliant on foreign demand. In 2023, overseas revenue accounted for only 15.6% of Goldwind’s total revenue (albeit up from 9.2% in 2022). And overseas revenue in 2022 accounted for just 4% of Mingyang’s total revenue and 1.6% of Windey’s. That stands in contrast to Chinese companies like CATL 宁德时代 (battery manufacturing) and Longi 隆基 (photovoltaics), where overseas revenue was 23% and 37%, respectively, of total revenue in 2022.

What Keeps the EU’s Wind Industry Up at Night

The worry for EU policymakers is that China’s wind industry is simply at an earlier stage of what has become a familiar process: widespread subsidization followed by a process of consolidation within China, causing suppliers to turn their capacity toward external markets to scrape by any margin they can get outside of China. These worries come at a time when flagship European producers have already been struggling, further deepening concerns that subsidized imports could damage the EU’s green-industrial base (see Figure 5).

To be sure, the EU’s angst perhaps ignores differences in development between wind and other clean-tech industries. For example, in its early stages of development, China’s solar industry was geared toward meeting external demand, particularly in Germany, where feed-in tariffs created an opening for Chinese producers. The same is not true for the country’s wind producers, which have been mainly serving domestic projects. These development differences, however, may be little consolation to European governments who have seen Chinese producers winning bids for turbine provisions across Europe.

Another dimension that complicates the picture: while the EU may be able to take steps to limit Chinese producers from participating in EU wind-procurement bids, much of Chinese wind producers’ internationalization has been focused on markets outside of the EU. From 2020 to 2023, an average of just over 21% of exports in value terms went to the EU (see Figure 6).

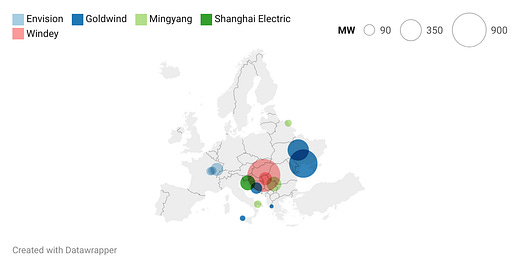

Some of the largest bids won by Envision last year were a 1.8-gigawatt green hydrogen project in Saudi Arabia and over 2 gigawatts of orders in India in 2023, with at least two of those bids for projects over 600 megawatts. Even some of the largest bids won by Chinese producers in Europe are in countries outside of the EU. For example, a massive 854-megawatt bid secured by Windey in northern Serbia in 2023 will be Europe’s largest onshore wind farm (See Figure 7).

As the growth of global wind installations begins to slow amid fierce competition from other renewables like solar, producers will be forced into more direct competition for potential projects. And if Chinese producers can provide low-price, high-quality alternatives to the likes of Vestas or Siemens — whether due to subsidization or innovation, or more likely a combination of both — then more of that market will accrue to them.

Complicating this picture is that a fair share of the blame for the decline of European producers lies at the feet of the producers themselves. Most notably, Siemens Gamesa has had ongoing problems with quality for two of its onshore wind turbine platforms, the 4.X and 5.X, forcing the firm to go to the German government for what ended up being a $8.1 billion bailout. It’s currently engaged in similar discussions with the Spanish government — little wonder, then, that Goldwind has announced it is looking into potential energy projects in Spain, one of the countries on which the Commission’s inquiry will focus.

Future Prospects

One could imagine a time when subsidized production in green tech — regardless of who was doing it — would have been lauded as a crucial step in fighting climate change. That sentiment is nowhere to be found today: the race to dominate the green industries of the future has quickened, and governments fear a zero-sum competition that will leave their workforces and industries behind.

EU policymakers may rush to protect an industry long considered to be emblematic of the bloc’s innovation in the green-tech space. Insulating domestic industry from competition, however, has real costs — not all of which are monetary. A protected industry can become a complacent one, and support could come at a time when producers need real market discipline. There’s also the question of how globally competitive European wind producers would be even with state support.

It’s also worth bearing in mind the potential impact such actions could have on broader efforts to decarbonize. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Chinese turbines delivered outside of China cost an average of 20% less than those made by European and American counterparts. Turbine prices within China dropped 11% in 2023. Especially for countries with no developed wind suppliers, these are meaningful cost reductions, which very well could pencil out previously infeasible investments in new wind capacity.

Additionally, if a more protectionist approach were taken by the EU — such as a preemptive duty following an inquiry — would China retaliate? Last year, China made clear that it understands its bottleneck position for several critical technologies when it announced export controls on germanium and gallium — key materials for semiconductor manufacturing — and later graphite, the predominant anode material for EV batteries. You don’t have to look far to find similar bottlenecks for the wind industry, with perhaps the most obvious candidate being neodymium magnets, of which China had a 92% market share in 2020, according to the US Department of Energy. Indeed, China already has restrictions on the export of rare-earth processing technology.

It remains unclear what the European Commission will do after the wind inquiry runs its course. What is clear, however, is that policymakers face difficult tradeoffs when it comes to preserving the international competitiveness of their domestic producers, potential Chinese retaliation, and the affordability of green tech.