Central Wuhan Hospital ER Head Whistleblower: "I Did What Any Doctor Would Do"

Also, her views from the chaos inside a hospital overcome with coronavirus patients

Some housekeeping: I’m changing the name of this newsletter and podcast to ChinaTalk. The coverage mix will stay the same.

On December 30th, Ai Fen, head of the emergency department of Wuhan’s hardest-hit hospital, saw a patient report of SARS coronavirus. She sent it along to her classmates and attempted to warn the local public health department and hospital higher-ups of the risk. The report quickly went viral among Wuhan’s medical circle, leading to eight doctors, including the now-deceased Li Wenliang, receiving reprimands.

This article details her experience trying to warn the system as well that of medical personnel on the front line.

This article spread like wildfire earlier this week until it was censored. People, a state-owned outlet, published the piece. Says Ryan Manuel of Official China, People is “owned and published by the People’s Daily group, itself an arm of the CCP. [It is] therefore subject to tight regulation and control over content and staffing, although as with most Chinese media, also forced to be profitable enough not to rely on state funding.” He believes that it got published in the first place because it wasn’t directly critical of the central government. Also, since People is a national level outlet, it was able to evade Wuhan censors.

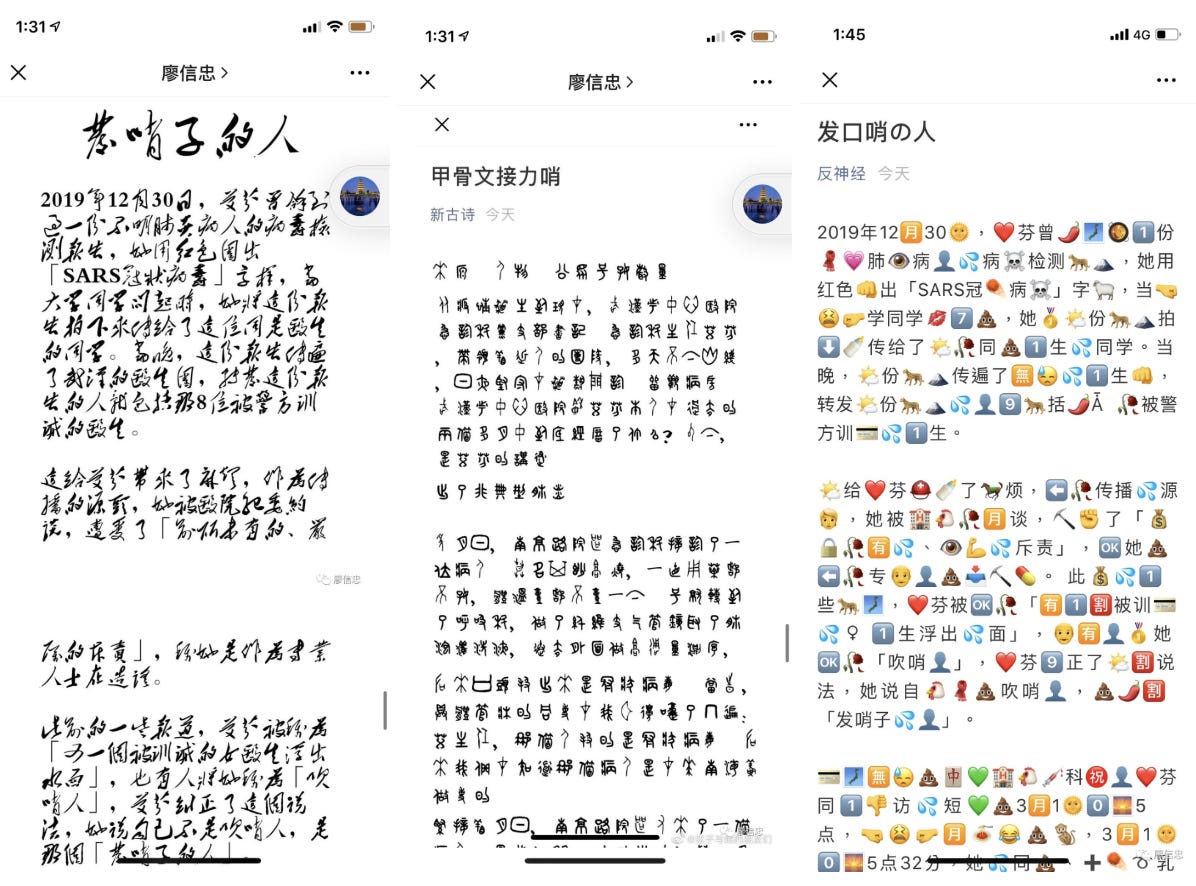

The reaction to this piece’s censorship has been remarkable. Netizens have come up with increasingly creative ways of getting around WeChat’s censorship to continue sharing the doctor’s reflections. My three favorites use Mao’s calligraphy, seal script (a 2500-year-old form of Chinese writing) and emoji. These efforts are more protest art than anything else, as some are barely readable. Also, I fear they’ll just be used to train algorithms in the future.

What’s depressing is how similar this feels to this recent NY Times article, which walked through the struggles of a Seattle epidemiologist through January to cut through red tape and get people to pay attention to the risk.

Read till the end for 'China Twitter Tweets of the Week.'

The Whistle Distributor

Published in People. By Gong Jingqi. See the full Chinese version alongside more coverage by the Chinese Media Project here.

The first section is in the reporter's voice.

At 5 am on March 1st, I received a text from Ai Fen, director of the Emergency Department in Wuhan Central Hospital, agreeing to the interview. Half an hour later, her colleague Jiang Xueqing, director of the Breast and Thyroid Center, passed away after falling ill with coronavirus. Two days later, Mei Zhongming, the hospital’s deputy director of ophthalmology, died. He and Li Wenliang were colleagues in the same department.

As of March 9th, 2020, four medical staff in Wuhan Central Hospital have died. Since the outbreak, this hospital, which is only a few kilometers away from the Wuhan Seafood Market, has had the most number of medical staff to fall ill from the virus. According to media reports, more than 200 people have become infected, including many senior personnel.

The shadow of death hangs over this hospital, Wuhan’s largest. One doctor tells People that no one among the medical staff discusses this; they only mourn quietly and talk in private.

There was a chance to avoid this tragedy. On December 30th, 2019, Ai Fen received a medical report about a patient with an unknown form of pneumonia. She drew a red circle around the words “SARS coronavirus.” When a medical school classmate asked her about it, she shared a photo of the report. That night, the report got sent around the Wuhan medical community, and the eight doctors [including the now-deceased Li Wenliang] were among those who shared the report and were later taken in for questioning by the police.

What follows is Aifen’s narrative, in her voice, written up by the reporter.

At 11:46 p.m. on Jan. 1, the hospital's control/surveillance department head 医院监察科科长 asked me to come in the morning.

I didn't sleep that night. I was anxious and thought it over and over. But I felt that there are always two sides to everything. Even though I created a bad influence, since I reminded the Wuhan medical personnel to get them to pay attention and be on guard, I figured this might not be such a bad thing. The next morning, a little after 8 a.m., before I could finish my shift, a phone call came urging me to go.

In the talk that followed, I received the harshest reprimand of my career.

At that time, the leader of the conversation said:

We can't hold our heads up when we go out for a meeting. Director so-and-so criticized our hospital saying Aifen, as the director of Wuhan Central Hospital Emergency Department, you’re a professional. How can you have no principles and no sense of team discipline to go around starting rumors and stirring up trouble?

That's the exact words. They then made me go back to the department of more than 200 people, and one by one either face to face or over the phone [not using a mass WeChat message] tell them to say nothing about the disease. “They can’t even tell their husbands”…

I was stunned. He didn't criticize for not working hard, but it seemed that I had singlehandedly ruined Wuhan’s development. I felt desperate. I was a conscientious, hard-working person. I felt that what I was doing was by the book, that it made sense. So what did I do wrong? I saw this report and reported it to my superiors at the hospital, to my [medical school] classmates. Then, people the medical circles began discussion without divulging any private information. If you encounter a patient with an important virus, and another doctor asks for information, how could you not tell them? That's your instinct as a doctor, right? What did I do wrong?

I did what a doctor, really what any person should do. If anyone else was in my situation, they’d all probably do the same thing.

I was also very emotional and said, I did this thing on my own, and it doesn’t involve anyone else, so if you want to, just hurry up and take me to jail. I said I was not fit to continue working in this position and wanted to take some time off. The leader did not agree, saying that right now is precisely the time to put me to the test.

I remember very clearly coming home that night and telling my husband that if anything happened to me, you better bring up our baby well. Our second child is still very small, just one year old. My husband was completely baffled as I didn't tell him that I had been reprimanded. On January 20th, after Zhong Nanshan said that the virus could spread from person to person, I told him what had happened that day. During that time, I just reminded my family not to go to crowded places and to wear masks when going out.

Lots of friends asked me if I was one of the eight doctors who was reprimanded? To tell the truth, I was not brought in by the Public Security Bureau. Afterward, friends asked me if I was the whistleblower? I told them no, I’m just the person who distributed the whistle.

很多人担心我也是那8个人之一被叫去训诫。实际上我没有被公安局训诫,后来有好朋友问我,你是不是吹哨人?我说我不是吹哨人,我是那个发哨子的人。

All the time I think that had they not reprimanded me but instead calmly discussed the situation’s cause and effects and brought experts in to discuss, maybe the situation would’ve been a little better. At least we could have shared our concerns within the hospital. If on January 1st everyone would’ve been more on guard, there wouldn’t have been as many tragedies.

In our department, because of increased awareness, not many medical personnel fell ill, unlike in other departments like Li Wenliang’s and Jiang Xueqing’s. They didn’t have the time or energy to make inquiries about this sort of thing. Maybe if they were able to hear the right advice in time, we wouldn’t have arrived at this day. So, as a person involved in this affair, I have huge regrets.

If I knew what I know today, I would have gone and told every damn person.

She then goes on to recount stories of the subsequent few weeks when the crisis was at its peak. Anything in paraphrased is in italics while straight translations are in regular font.

On January 21rd, the emergency room had 1523 sick people, three times more than their previous most busy day. Patients were rushing forth from all directions, and behind them, the streets were completely jammed up.

One patient’s family member waited in line for hours. When he finally got to see a doctor, he said that his father was sick and still in the car. Since the parking lot was full, the doctor had to walk far to check on the man. By the time they arrived, the father had already died.

Before, if you made a small mistake like you weren’t on time for a scheduled injection, patients would make a huge fuss. But now no-one acts that way. Everyone was just going about as if they were in shock.

When the patients die, it’s very rare to see family members crying because there are too, too many. Some families didn't even plead with us to save them. Instead, they'd sigh and say, 'At this point, please just let them pass quickly.'

They're now is scared of spending time in the hospital since they fear getting infected themselves.

Before the coronavirus, the sorts of patients we got in the emergency room we always had a standardized way of handling. That level of busyness was an extremely satisfying one. But this time handling so many sick people and being unable to help and unable to find them beds, this sort of busy leaves you helpless and pained.

Many doctors have a tough time emotionally. Coming across such a crazy situation, some doctors and nurses just cry, on behalf of others and themselves, as every day they aren’t sure when will be the day they catch the sickness themselves.

Towards the end of January, our hospital’s leadership one by one fell ill. So during that time, we basically had no management, and it felt like, ‘well, we just gotta stand there and fight’ that sort of feeling.

40 employees of the emergency department fell ill with coronavirus. In their wechat group (named the “Jia You Group”) they often discussed their health situation. Often their heart rates stayed around 120 beats per minute. Even if they don’t’ die from the disease, they have no idea if one day their health will be impacted. Many doctors are now thinking of resigning.

On February 21st, I had a meeting with a leader at the hospital. I wanted to ask him whether or not the criticism I received was right. I wanted an apology, but I didn’t dare ask. To this day, no-one has expressed to me any sense of remorse. But this experience makes me believe even more that everyone must maintain their independent thinking because there need to be people to take a stand and speak the truth.

Thanks to Izzy, Tony, and Athena for help translating.

China Twitter Tweets of the Week

[the first one is from a parody account]

Isaac was on a ‘roll’ this week…

response to last week’s newsletter: