The following article was written by Tianyi Xu, a sophomore at Bowdoin. Let me know if you find this interesting as I’m thinking of kicking off a series of deep dives into mainstream Chinese commentators’ political ideologies.

Online political discourse in China consists of more than one-note nationalist commentary from the Global Times. Even within the confined boundaries of censor-approved speech, divergent viewpoints on US-China can be found.

Ren Yi is one such blogger. Better known by his alias, Chairman Rabbit (he had a pet rabbit as a child), Ren is the son of a prominent Chinese reformer in the ’80s. His commentary on Hong Kong and Covid-19 seemed to channel the views of a growing cohort of educated young adults in China who are now more disillusioned than ever by the West’s perceived bad faith. Ren’s punditry is a unique addition to the bitter, ongoing fight over political allegiances of younger generations in China.

He picks his battles to work around censorship and mainstream opinion, incorporating both the dominant nationalist viewpoint and novel ideas of progressive socialism in China.

Working within China’s ruling elite ideology

A self-described commentator of “mass-histories, mass-societies, independence, rationality, critique and construction,” Ren’s works fuse with China’s ruling ideology and are largely spared by censors. His writing style comes off as sincere and accessible to college-educated audiences, and he often explores current events by tracing their historical, philosophical and political origins. One of the most telling articles that achieve this feat is “Why the United States Can’t Understand China—From the Founding Wishes of the Chinese Community Party to the European Civilization to American Politics,” published on July 18 of last year. In it, Ren draws contrasts the founding stories of China and the U.S., arguing that the former is based on ethnic solidarity while the latter builds on shared political values.

To him, the “great unification” (大一统) of the Chinese people differs from the European model of decentralized, fractured states. Therefore, for him the very origins of American diversity make the American system intrinsically unable to understand the Chinese way of life, an inability that sparks misunderstanding and conflict:

China built a supra-ethnic, traditional-civilization nation through imposing uniform writing systems and a strong culture of centralized rule, while the United States, through its unique political values, built a supra-ethnic, political-civilization state as a solution to Europe’s incessant ethnic discord. There is no ethnicity in the U.S., only united political values. [Emphasis added]…

The U.S. has eliminated the “ethnic,” and has grown used to defining themselves through political values. The relationship the U.S. maintains with the world is about likeness: figuring out which countries share their political values. Whoever challenges America’s political values amount to enemies of the state…

When they see the Chinese Communist Party and its political label of communism, they automatically go on high alert: “The C.C.P. is a menacing force to fundamental American values and ideology. The expansion and development of the Party is an existential threat to the United States, so the full weight of the state must be thrown behind a combative stance.”

In another article, Ren expands on the theme by reconciling Marxist-Leninism and post-reform China. He strategically distances the Communist Party from its namesake and dubs it “the China Party” (中国党). Ren argues that the C.C.P has evolved and that the present-day Party is an unprecedented fusion between a conflict-driven Western ideology (Marxism) and harmony-based Chinese politics. He explains the odd position of the C.C.P.’s on the spectrum between communism and capitalism:

The China Party today not only possesses the methodology of Marxism’s dialectical materialism and full consciousness of political and economic realities, it also incorporates the organic, harmonious and symbiotic elements from the core teachings of Confucianism. Co-opting the West’s paradigms of capitalism/market economy helps motivate individuals and safeguard their rights, thereby invigorating creativity. I think that the process might not be smooth-sailing, but it’s in the right direction—China is actually building a higher-order organizational structure of the society.

The conflict-based Western thought also influences China. On the one hand, it limits the options in the minds of Chinese people and forces China into a similarly combative stance; on the other, it signal-boosts hawkish and extreme rhetoric within China’s discourse (“a war is inevitable”). The result would be self-fulfilling prophecy whereby a cascading crisis would result in an eventual conflict.

Keep your friends close and your enemies closer

Ren argues that China’s populace could benefit from his discussions of the United States and of the intricacies within its society and government through virtue of “knowing thy enemies” (知己知彼,百战不殆). This sets him apart from other mainland pundits who prefer rousing, provocative statements denouncing America. In an August 24, 2020 article, he addresses the partisan attitudes toward China in the U.S.

To the American people who are now confronting such a grim national crisis, the last thing they want is a military skirmish or even war with China. The issue is so remote that it never even entered their minds.

But to Chinese people—including highly educated ones—an open war between the two countries seems like an imminent threat.

This cognitive disconnect represents a certain asymmetry: to Chinese people, China is a great obstacle in the eyes of Americans, a major part of U.S. political and social discourses, and that a conflict is already in the making. To the Americans: “China? What?”

Rest assured that China is not the primary issue in U.S. politics.

A perpetual, carefully crafted ideological struggle

An advocate for “consensus politics,” Ren has never been reluctant to lecture the United States on its government’s failings. In trying to educate the Chinese internet on the intricacies of the American system, his aim is to paint an authoritative picture of the U.S. public and its political landscape, while juxtaposing that picture against a superior Chinese system.

Ren blames US culture for its lack of consensus in its political system. Ren refuses to draw any similarities between the two world powers. He chides America’s dedication to “originalist, dogmatic free market capitalism” (原教旨自由市场资本主义) that, combined with its cultural foundations, underlies most of its systemic failings. In a June 23 article attacking what he viewed as America’s cultural and systemic shortcomings, Ren puts forth a “thirteen sins” of the nation’s sloppy response to Covid-19:

The dual sovereignties of federal and local governments;

The dissociation between the three branches of government;

Stark racial and class hierarchies;

The supremacy of individualism—even as to pose the society/public as an adversary;

The tunnel-vision emphasis on political and civil rights;

The “gun” culture—manifest destiny, “rugged individualism,” “the fighting people”;

Biblical culture and anti-intelligence culture;

Multicultural society devoid of consensus politics;

Divisive politics and media as opposed to healing ones;

Lack of elderly-supportive values; neglectful of care for elderlies;

Familial structures adverse to containment of Covid-19;

Lack of social safety net;

Cultural opposition including a rejection of masks.

At the core of these failures, he argues, the United States should be forced to reckon with some institutional inevitabilities. Echoing the state position which maintains that China possesses “institutional advantages” (制度优越性) in handling Covid-19, Ren offers the following:

There is no possibility of effective containment [of Covid] in a place so repulsed by even the most basic measures of mandatory quarantine, mass-level cordoning and population flow control; it is an impossible feat in an individualistic society dominated by anti-science sentiments and so perpetually in thrall to philosophies of personal privacy that ruled out even the popularization of health QR codes. These factors won’t simply disappear with a different president. Were Obama, Hillary [Clinton] or Biden president, the efforts might be more effective since a presidential figure would at least endorse sensible public health measures—but this won’t fundamentally change the course of the pandemic. The control of the pandemic is not about the abilities of the executive but rather a thorough, interconnected system of governments all throughout the nation coordinating public health responses. Public authority (公权力) must be allowed to execute its policies effectively, consistently and exhaustively, without fractured edicts differing on each level, mixed up with judicial and administrative hindrances. The public and the society must prepare to collectively cede… [some] so-called political and civil rights.

The entire design of America’s political-legal infrastructure serves to forbid these practices. The separation of power marks the core of American politics. Political and civil rights are the cornerstone of American values. Negating these would amount to negating America itself.

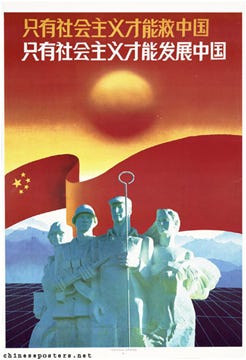

In some ways, by examining the underbelly of America’s governance structure for the sake of public education, Ren’s critiques resemble those from left-wing political commentators in the U.S. Trump’s incompetence became the most prized ammunition in his creative arsenal. In an article series titled “Only Socialism Can Save America,” (playing on the propagandist saying of “only socialism can save China”) Ren advanced the view that the American system thrives on chaos, as opposed to the Chinese system that placates them.

As a multicultural nation emphasizing personal liberties and rights, the United States is made up of an incredibly complex array of communities and ethnic groups. Because of these differences, they are “assigned” into different “political tribes” [sic.]. Ethnic politics, tribal politics, cultural politics and identities politics are the dominant strains of American politics, while left-wing politics sets out to advance class welfare, requiring the activation of class politics. In the U.S., this is no easy feat since white and Black workers don’t consider themselves belonging to the same class at all, but rather members of different “tribes.” Instead to Black Americans, Black elites and Black blue-collar workers share more commonalities and heritage.

As Marx would say, in this communally fractured society, the bourgeoisie successfully manipulated the discord between the working people to eliminate class politics.

Indeed, while reluctant to apply them to Chinese contexts, many of Ren’s diatribes against the U.S. hinge on Marxist paradigms of false class consciousness and the usurpation of public power through seemingly legitimate means. In the case of Trump and Covid, the legal system served to illustrate his point. The following passage discusses the “veneration of the American judiciary”:

The main problem facing the U.S. is that the constitution has become unchangeable in the twenty-first century. Different political communities hold vastly divergent views on the same constitution, unable to commit to dialogues by virtue of their membership in different political tribes. Under a given constitution, politicians can only legislate under a static framework; in thrall to the separation of powers, the courts possess considerable influence, and the opinions of judges have become paramount, ascending as the de facto elite rulers of the society. Judges are empowered to decide the fate of issues ranging from Obamacare and the Muslim ban to Covid-19 regulations and abortions.

Political tribalism, according to Ren, results in fragmented realities where citizens’ priorities do not align with their interests. Working-class people, instead of being empowered with the will to challenge establishment politics, are instead distracted by trivialities. To him, these comprise hot button social issues like the transgender bathroom debate, same-sex marriage and abortion. These topics that galvanize both sides of American politics are nothing but illusive apparatuses used by the ruling elites to distract focus from, say, inequality.

Public intellectualism: an out-of-place identity in a populist society

Appealing to a populist message currently espoused by the ruling party requires walking a delicate line as not to draw the ire of his audience: censors who stand ready to redact any discrepancies and tech-savvy young people quick to boycott any “politically incorrect” sentiments. For instance, just this past week, a piece where he expressed his fascination with the popular new social media platform Clubhouse got taken down mere hours after its publication, coinciding with a nationwide block of the app. He has also been fiercely criticized for advocating a softer line China’s handling of Australia.

You Shu had a long thread on what Ren’s detractors said in this case. Some sample popular comments he translated:

He concludes:

In another instance, in a rebuke of a popular, politically correct refrain on Chinese social media, Ren chastised the practice of labeling opinionated netizens with the sarcastic term “public intellectuals.” Ren writes:

Public intellectual is a noble profession to me. In the West, they are people who are intelligent, educated and willing to take responsibilities and risks. But in China, somehow, the entire meaning of the word came to represent a specific political view. You get labeled as a public intellectual if you believe a certain set of things, but it doesn’t matter whether you have integrity or not.

Ren’s platform strategically analyzes contentious areas of Chinese politics. His perspectives are still fundamentally in line with the government, but he has managed to bring a sheen of reason and intellect to discourse usually dominated by nationalist shouting.

For a “modern” audience of young and energized participants of political discourse, Ren’s work provides valuable political identification without the filters and pretense of bureaucratic propaganda pieces. His new-age platform is a product of a nation rapidly coming to terms with China’s evolving place in the world.

A few weeks ago, Ren published a poignant obituary for Ezra F. Vogel alongside a selection of his correspondence. Departing from his usual polemics, the obituary shows Ren as introspective, as he explained the motivations of his work:

Professor Vogel influenced me greatly. His pedagogy, his integrity; his generosity and his smile. I remember them clear as day. I thank him for this mentorship, imparting to me knowledge, clarity and wisdom. I owe my gratitude to his trust, his opportunities and his care. To this day, I still commit to writing in my free time, in the spirit of continuing his mission and thoughts: spreading knowledge, telling stories of China, facilitating the fusion of civilizations, and pushing our world forward.

China Twitter Tweets of the Week

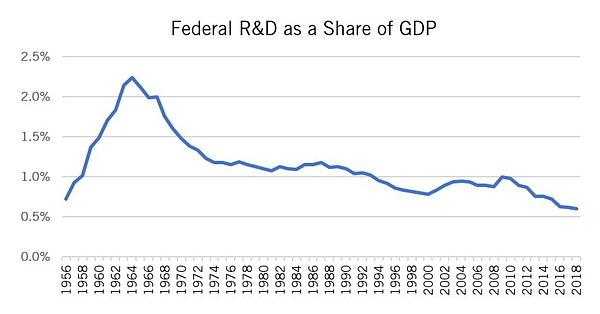

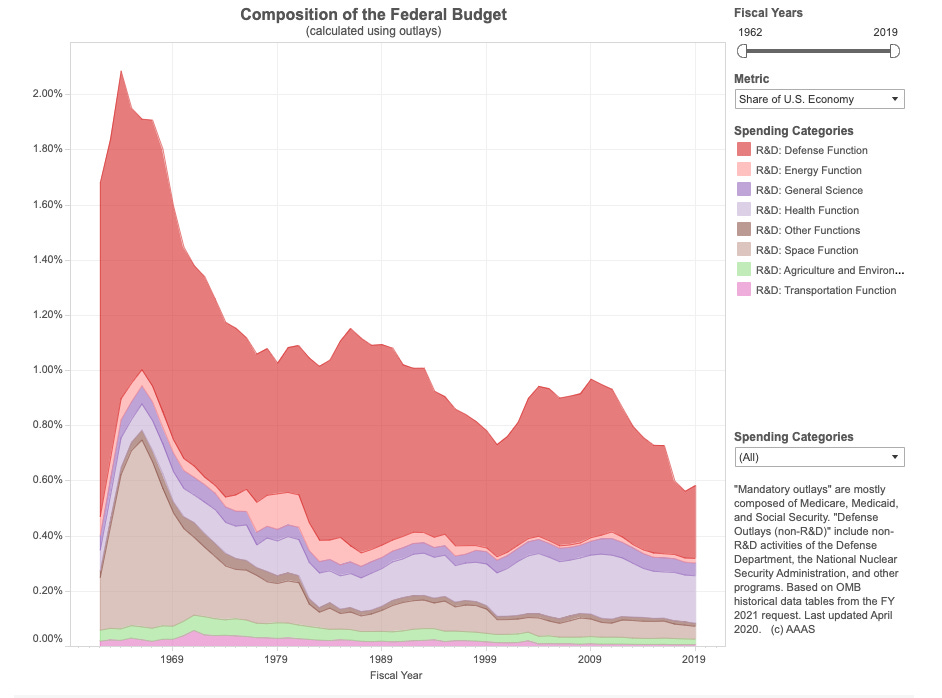

Key chart!

Here there is no dramatic decline. There is a decline, but rather than the almost fourfold drop in the headline figure, the drop here would be, peak to bottom, less than 2x. This may be even less dramatic if we consider that a lot of that energy R&D may have been for nuclear weapons development.

Very happy video.

Interviewing Shen Lu today for ChinaTalk! What should I ask her?

Title: Netsuke of Young Sparrow

Period: Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period (1868–1912)

Date: 19th century

This is absolutely fantastic. An invaluable resource.