I spent two years in a China Studies master’s program. It was fun reading Dream of the Red Chamber and Xi speeches — but I really wish I had come out of it with some hard skills, too. Had I only known about the University of San Francisco’s new Master of Science in Applied Economics, I could have learned something to make me fit for the job market of the 2020s: Python, data visualization, machine learning, A/B testing, all the good stuff you increasingly need for policy jobs in DC. With this MS degree, you can part of the “AI talent surge” that Biden has been pitching!

Study the economics of online platforms, big data, and artificial intelligence at the same time as you learn the practical tools of econometrics, experimentation, and coding. Plus, for those non-US students out there: this program is designated as STEM, meaning you can apply for a three-year extension on your student visa to get US work experience after you graduate. To learn more and get an application fee waiver, go to usfca.edu/talk.

The following was written by anonymous contributor “Masa Rick.”

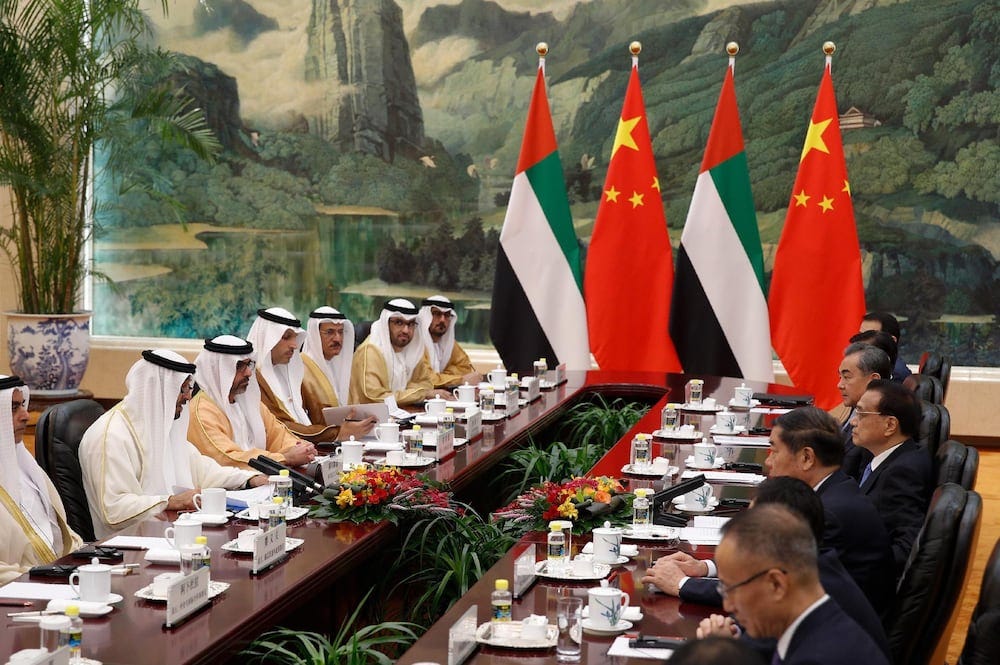

In recent years, China and the Middle East have notably strengthened their economic ties. While of course energy shipments remain high, non-oil trade has significantly increased as well. Last year, China, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia arranged for a 50-billion-yuan currency swap, and BRICS invited Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE to join the bloc (the UAE has already joined, while Saudi Arabia is still undecided). This deepening economic engagement underscores how both regions see mutual benefits in cooperation, and why they are paving the way for more diplomatic, technological, and cultural exchanges.

But China has a growing interest in the Middle East for another important reason: artificial intelligence. China’s AI prowess is marked by its vibrant startup ecosystem and its success in raking in billions of dollars in international investments every year. The Middle East, with its growing emphasis on technology and innovation, has become another attractive destination for Chinese AI companies seeking strategic partnerships, market access, and regional influence.

Market Access, Diversification, and Geopolitics

Many Middle East nations — notably the richer Gulf States like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar — are actively seeking to diversify away from being predominantly energy exporters and toward becoming hubs of innovation. Riyadh articulated that goal in 2016 through its “Vision 2030” program, which seeks to encourage private-sector innovation, particularly technological advancement. Similarly, Abu Dhabi established a technology investment firm called MGX — led by the sovereign fund and the quasi-state firm G42 — to target investments in AI and semiconductors; in a few years, MGX is likely to have over $100 billion in assets.

This shift makes the Middle East an attractive market for Chinese tech companies, many of which have taken advantage of the Gulf States’ strategic pivot for economic diversification to forge closer ties and push for heightened technological cooperation. Many regard the Gulf States as experimental grounds for more opportunities in Middle East and Global South emerging markets.

Closer economic cooperation also folds nicely into China’s geopolitical ambitions in the region. China already has a military presence in Djibouti, and last year it brokered a peace agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Though the US has a long-standing military presence in the Gulf, including the Al Dhafra Air Base, earlier this year the UAE and China participated in joint air-force training, solidifying their comprehensive partnership status beyond just MOUs.

AI investments can serve as another tool to solidify these relationships beyond oil sales, financial coupling, and joint military exercises. Both China and the Gulf States, in their calculation, see a promising symbiosis:

China, while freeriding off the US security framework in the Middle East (as exemplified by the recent Houthi attacks), can benefit from technological co-development in Middle Eastern hubs.

The Middle East, meanwhile, benefits from China’s manufacturing and technological knowhow, catapulting their own non-energy development, all without compromising their relationship with the West (at least not yet).

So far, the development of artificial intelligence by Chinese entities in the Gulf has been dominated by large Chinese corporations with government ties — in particular, Huawei and SenseTime. Huawei recently opened a data center in Riyadh and promised over $400 million investment in Saudi Arabia’s cloud sector over the next five years. SenseTime, too, has joined the AI bandwagon, pledging to help Saudi Arabia build smart cities, stimulate digital tourism, and implement surveillance infrastructure in Saudi Arabia’s ambitious trillion-dollar project to build a city in the desert: NEOM. (The name is a portmanteau of “neo,” as in new, and “m,” as in Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.)

Chinese collaboration with Middle East universities is also strong — in particular, its ties to Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) and the UAE’s Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence (MBZUAI), the latter of which is the world’s first AI research university, currently led by Chinese-born American computer scientist Eric Poe Xing 邢波. China has been busy sending researchers to the Arab world: according to KAUST, “approximately 20% of KAUST’s students, 34% of its postdoctoral researchers, and 9% of its distinguished faculty are from mainland China.”

Perhaps the greatest value-add of collaborating with Middle East academia: skirting US chip sanctions and accessing advanced semiconductors. China already receives most of its advanced semiconductors for AI development through intermediaries. So it should be no surprise that institutions like KAUST and MBZUAI have placed orders on 3,000 of Nvidia’s most advanced chips for AI research. In response, the US has sanctioned China for receiving those shipments and expanded the scope of its export controls to some (publicly unspecified) Middle East nations. The US has a delicate balance to manage: the security risks of China obtaining advanced semiconductors through the Middle East on the one hand, and the commercial interests of American, Dutch, and South Korean companies on the other.

Potential Implications

The growing integration of AI between China and the Middle East will require compatible regulatory frameworks. Presently, Middle East nations’ AI regulations do not operate under a uniform framework. China’s current AI regulatory framework, meanwhile, somewhat resembles the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) — although some have noted that the measures on AI research, personal data, and privacy regulations are extremely vague. So it’s unclear, then, which data-protection or AI regulation to follow when China engages with AI actors in the Middle East; that ambiguity will create challenges for regulators and may well cause market disruptions.

Middle East nations risk developing a technological dependence on China; avoiding that trap will require carefully managing its China partnerships to ensure a balanced, mutually beneficial relationship. In terms of AI and cyberspace development, most Middle East nations — including Saudi Arabia and the UAE — still adopt the “we are learning from China” rhetoric. Even so, less economically developed countries like Egypt and Iran view Chinese technological assistance and knowledge transfer as a necessary path to achieve technological progress in their own countries.

The Middle East is a key target-rich area for the Belt and Road Initiative. But many of the infrastructure-project recipients in the Middle East have raised concerns over the lack of transparency as well as debt sustainability worries for poorer countries in the region. The integration of digital infrastructure with physical infrastructure — or the “Digital Silk Road” — is a key component of the BRI. Some Middle East nations, like Iran and Egypt, already depend on the Chinese government and SOEs for concessionary loans or accessible capital to fund their domestic infrastructure projects — so the future of an even more pronounced asymmetric interdependence of debt-ridden Middle East on China is not too farfetched.

Further, as mentioned above, China could circumvent US chips sanctions through its cooperation with Middle East institutions. US lawmakers thus have another loophole to close — and Middle East nations will likely continue to be embroiled in the resulting geopolitical standoff between the US and China. In short, they will have to choose a side. For instance,

Just this month, a Saudi-backed venture capital fund was forced to sell its shares in an OpenAI subsidiary (known as Rain AI, a company that researches AI based on neural networks) due to its ties with Chinese investors.

In another high-profile case, the Emirati AI and biotech firm G42 came under scrutiny by US officials: American intelligence agencies warned that G42 has been working for China, funneling thousands of US-citizen biometrics to Chinese companies through collecting COVID test kits. G42 chose the US this time: its CEO, Xiao Peng 肖鹏, signaled that the firm “would phase out hardware purchases from Huawei’’ — but not before candidly asserting, “We cannot work with both sides. We can’t.” (Also of note: before joining G42, Xiao was the COO of Yitu Technology 依图科技, a Chinese AI firm sanctioned by the US government for its deployment of mass surveillance software.)

Middle East AI collaboration with China also raises significant human rights concerns, with potential repercussions that extend beyond technological advancements. The complicity of certain Middle Eastern nations — Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE — in deporting or detaining Uyghurs at China’s behest reflects a troubling disregard for human rights. Most Middle East nations support China’s rhetoric of treating the question of Uyghur rights as a counter-terrorism measure and lend rhetorical and physical support to Chinese policing of Uyghurs overseas. China’s use of AI-enhanced facial recognition for surveillance and control, exemplified by its strict surveillance of its ethnic minorities, has been widely criticized for violating individual freedoms.

Further AI collaboration, then, could potentially empower oppressive regimes, enabling them to enhance surveillance capabilities, stifle dissent, and curtail privacy rights. After all, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the UAE have some of the lowest Freedom House scores. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have been using Chinese surveillance technology to keep tabs on their citizens. NEOM is no exception either: Chinese surveillance technology will be deployed in this futuristic Saudi megaproject to monitor its citizens. In Iran, where morality police are known for strict social monitoring, the application of advanced AI exacerbated human rights abuses, enabling women to be easily identified in vehicles by the police and punishing improper hijab wear in public and private spaces. As Middle East nations embrace Chinese AI technologies, there is a risk of reinforcing authoritarian practices and compromising individual freedoms.

China’s strategic investments in Middle East AI mark a symbiotic relationship driven by geopolitical influence and economic interests. To be sure, China is unlikely to engage with the Middle East on a deeper level, politically or militarily for now — it prefers non-intervention and avoiding entrapment. But that makes its recent AI collaboration with the Gulf States all the more striking.

As dynamics in the region continue to evolve, it will be important to stay abreast of the development of AI exchanges between the Middle East and China. It’s hard to say who will be the winner of this strategic alignment — but in any case, assuming the US continues its sanctions on Chinese companies and institutions, the current state of equilibrium can’t last forever.

Great piece. Big connections here with recent essay by Chestnut Greitens and Kardon: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/playing-both-sides-us-chinese-rivalry