Taiwan and China on the Leak

Lily Ottinger and Nicholas Welch report:

The Trump administration leaked its plans to bomb the Houthis by accidentally adding The Atlantic’s editor-in-chief to a Signal group chat. This situation calls for humor, so we curated a mini-roundup of reactions from the Sinosphere. Enjoy!

From the Taiwanese platform PTT:

(Pushed) “I wonder what the American ancestors would think when they see these unworthy descendants.”

(Pushed) “I shouldn’t, but I really want to see the Indo-Pacific war plan leaked…”

(Pushed) “This is too ridiculous. Could it be because the reporter just happened to have the same name as the person they wanted?”

Indeed, such an error would be more difficult to make in Chinese given the huge variety of characters used in Chinese names. From Weibo:

American names are too simple. … 😂

This is truly an epic level of face-losing disgrace. (这是史诗级别的丢人现眼)

The following comments come from another Weibo post about Trump’s response to the leak:

“I don’t know, that didn’t happen” has hoodlum energy (無賴嘴臉)

Shameless people are invincible (人不要脸,天下无敌)

Another commenter in that thread invoked the phrase, “Not listening! Not listening! The turtle is chanting buddhist scriptures!” (不听不听王八念经). This meme is originally from a nursery rhyme satirizing people who shut down when confronted with an opposing viewpoint.

Some other relevant Chinese idioms:

泄露天机 (xiè lòu tiān jī) — “To divulge the will of heaven”

掩耳盗铃 (yǎn ěr dào líng) — “Covering one's ears while stealing a bell”

事后诸葛亮 (shì hòu zhū gě liàng) — “To become Zhuge Liang after the fact” — Zhuge Liang was a military strategist widely regarded as a genius thanks to his portrayal in Romance of the Three Kingdoms. This is a bit like saying, “Everyone’s an Einstein in hindsight.”

Emergent Ventures Grants for Taiwan

Jordan Schneider reports:

Tyler Cowen’s Emergent Ventures fellowship is a special institution. It is a no-overhead fellowship where Tyler reads short essays and gives grants to individuals to support personal projects and career development. Emergent Ventures recently received a donation to start finding talent in Taiwan and is looking for applicants. If you are or know anyone who could use a grant to get a personal project off the ground, do consider applying and select Taiwan on the regional dropdown menu!

For some inspiration, see here for an article on Tyler’s selection critera and a site that has compiled brief descriptions of all the past winners who’ve done things like use AI to decipher ancient text, compose Bach-style fugues, cover local politics, and a thousand other things.

Emergent Ventures helped get ChinaTalk off the ground, giving me a grant in 2018 to buy microphones and Chinese lessons. I’ve since attended three conferences (which I count as some of the most exciting weekends of my life), and met up with winners from around the world. What I’ve taken most from this community is a renewed optimism in what the future can bring and an ambition that I can continue to improve and broaden what I do and really make a dent.

Mark Carney — China Nerd?

Irene Zhang reports:

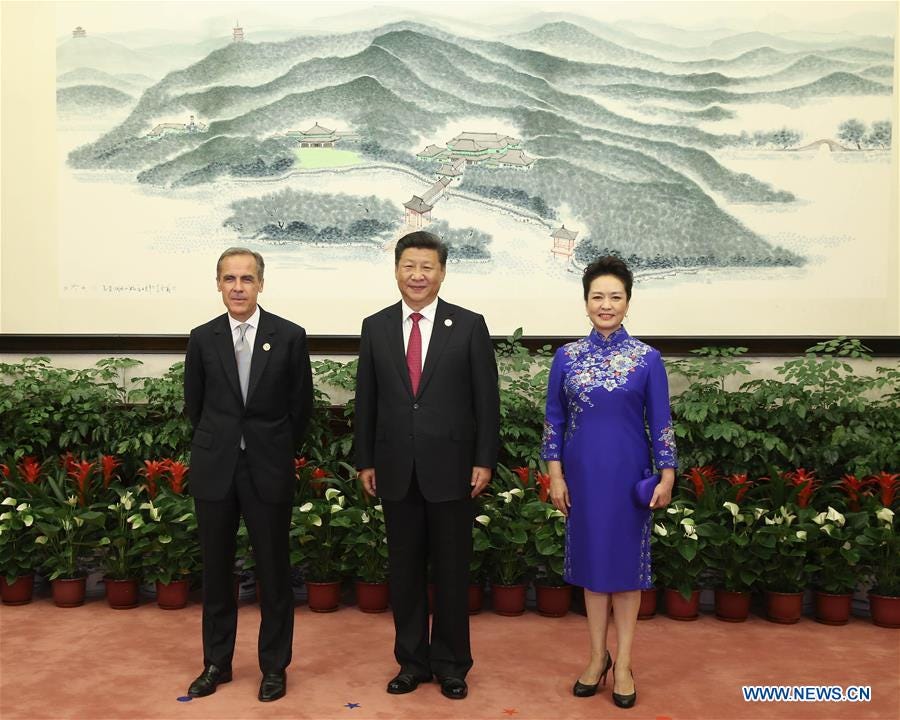

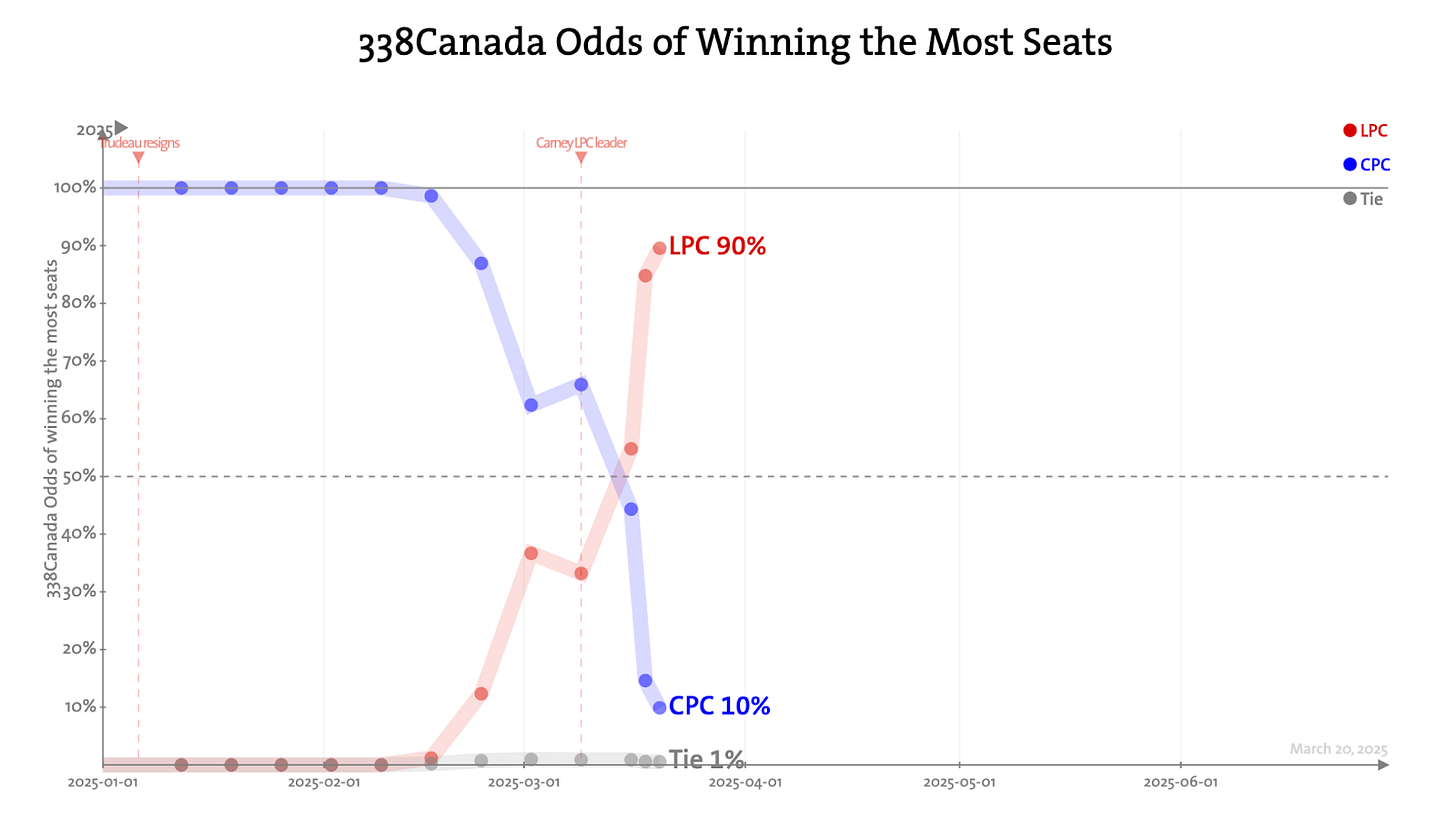

It’s official: Mark Carney is Canada’s 24th Prime Minister. The prominent economist and political novice, who led the Bank of Canada through the 2008 financial crisis and headed the Bank of England from 2013 to 2020, won the incumbent Liberal Party’s leadership contest on March 9 and was sworn in as Prime Minister on March 14. (In Canada, the leader of the largest party or coalition in Parliament becomes Prime Minister, making Mark Carney an oddity as a PM who doesn’t represent a constituency of his own.)

Britain voted to leave the European Union in 2016, three years after Carney became the first foreign head of the Bank of England. In the ensuing years, Carney worked to open the UK to new trading opportunities — including China. He traveled to Beijing with Britain’s then-finance minister in late 2017 to seek a $1.34 billion trade deal, though a UK-China free trade agreement never materialized. Along the way, he’s had to wade through choppy waters. In August 2019, as Chinese paramilitary troops amassed near the Shenzhen-Hong Kong border and protests in Hong Kong reached a boiling point, Carney awkwardly pulled out of a high-profile dinner in London with China’s ambassador to the UK. He faced criticism from the British political arena for bending over backwards to promote Chinese investment at a time when China was repeatedly violating human rights in Hong Kong.

Carney’s successful banking career comes with a special level of insight into China’s economic situation. He was bullish on the Chinese economy as of 2012, calling on Canadian firms to adopt China strategies and “reorient” toward China. But at least as early as 2018, he became deeply concerned about China’s domestic financial situation. During a BBC interview, he warned that China was one of the top risks to the global economy because its financial sector “has many of the same assumptions that were made in the run-up to the last financial crisis.” He elaborated on this in February 2019, telling a Financial Times audience that the possibility of a Chinese economic slowdown the second-most-important risk to global growth:

“While China’s economic miracle over the past three decades has been extraordinary, its post-crisis performance has relied increasingly on one of the largest and longest running credit booms ever, with an associated explosion of shadow banking. … The Bank of England estimates that a 3% drop in Chinese GDP would knock one per cent off global activity, including half a per cent off each of UK, US, and euro area GDP, through trade, commodities and financial market channels. A harder landing would have significantly larger effects, as these channels would likely be accompanied by negative spillovers to global confidence.”

Later that year he called the world’s reliance on the USD as the reserve currency “risky”, but said the Chinese RMB was far from ready to step in as a replacement.

Carney arrives in Ottawa with some knowledge of the top man himself — he met Xi Jinping twice while heading the Bank of England: once in 2017 and once in 2019. Last year, when rumors about him running to replace Trudeau first began to swirl, Carney met Xi Jinping again at the China Development Forum in March as head of Bloomberg’s board. These previous run-ins may not count for much in the short term, as Canada-China relations remain on ice. Just one day before Carney was elected to lead the Liberals — and by extension Canada, for now — China slapped 100% tariffs on Canadian rapeseed oil, oil cakes, and pea imports, as well as a 25% tariff on seafood. These are in retaliation to the 100% EV tariffs and 25% steel and aluminum tariffs Canada imposed on China last October, a coordinated move with the US at a time when relations between Washington and Ottawa looked very different.

What do you do when you get into a tariff war with your second-biggest trading partner to help your biggest trading partner, but now your biggest trading partner keeps talking about annexing you while trying to decimate your economy? You elect a central banker, of course.

Carney’s technocratic appeal was already compelling to voters as Canada struggled with productivity stagnation — now, the trade war is only adding to his political edge. A federal election is required to happen in Canada before October 20 this year. Before Trump made anti-Canadianism his newest fixation, the incumbent Liberals were set for massive losses while opposition Conservatives hoped for a majority in Parliament. But Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre’s previous amiability towards the American president has practically doomed him to quisling status only two months later, and now some polls predict Carney’s Liberals could even win a majority if the election were called today. The events have been quite jaw-dropping, and the polls still contain much volatility, but if Carney manages to cement his mandate, he will lead Canada through unprecedented headwinds on both American and Chinese frontiers.

Mood Music — Canadian Disco:

Why China Doesn’t (Really) Frack

Caleb Harding reports:

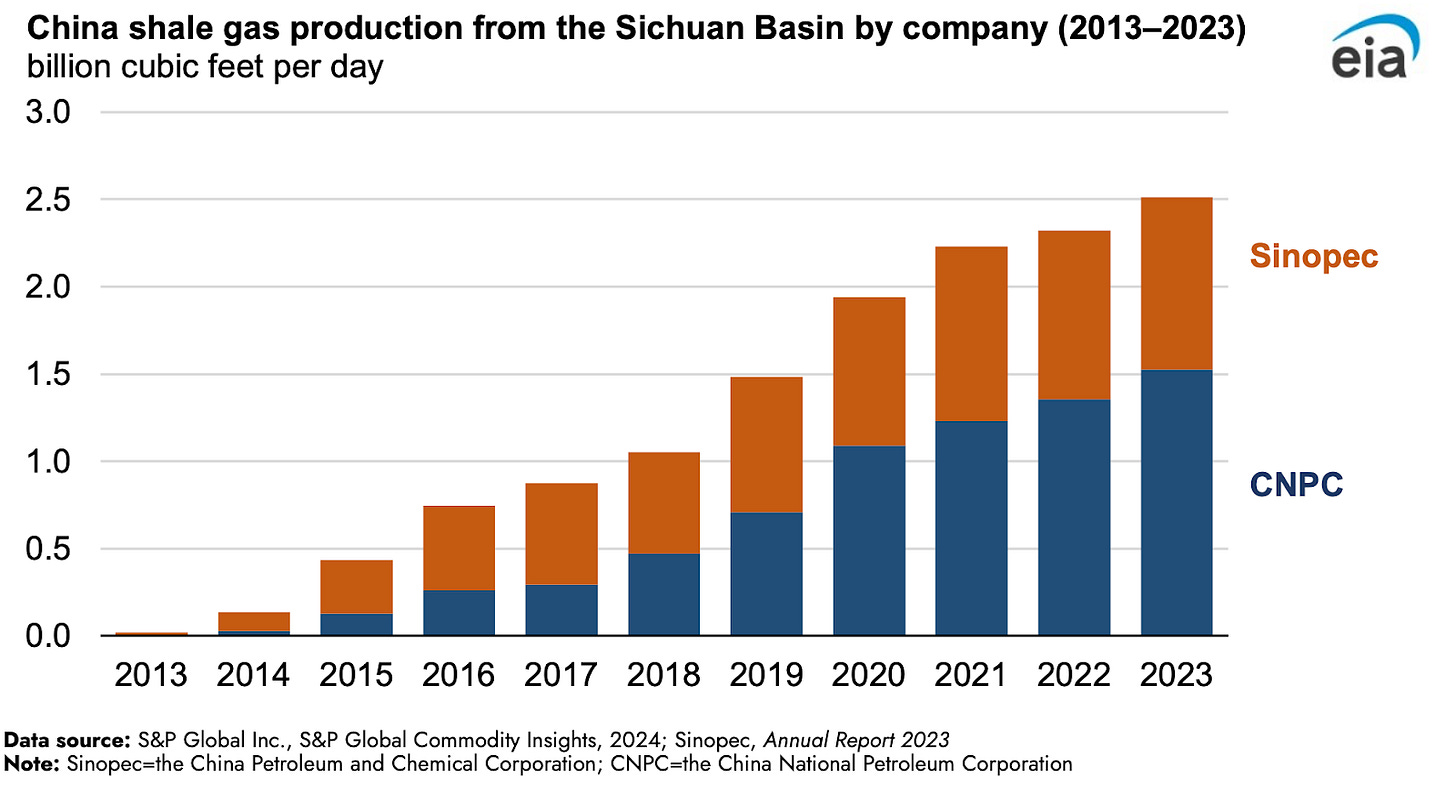

China’s natural resource endowments have been succinctly summed up as “Rich coal, poor oil, small gas” (“富煤、贫油、少气”). Despite claiming “small gas,” however, China actually has the world’s largest reserves of shale gas, an unconventional type of methane deposit that must be tapped with hydraulic fracturing. China is one of only four countries in the world with commercial fracking operations (the others being the USA, Canada, and Argentina), which began after President Obama shared fracking technology with the PRC in 2009.

Chinese media acknowledges that the shale gas revolution was a game changer for U.S. energy supply and security, but China has yet to realize its own revolution with its immense reserves — why? The simple answer is geology.

China’s shale reserves are deeper, more scattered, and in more mountainous terrain than those in the United States. Guo Tonglou 郭彤楼 is a chief engineer at Sinopec, one of just two companies involved in commercial scale extraction of shale gas in China. Commenting on China’s situation, he said that, “Although we are a country rich in shale gas resources, shale gas extraction in our country is difficult and costly. This means that it is impossible for us to adopt the same development approach as the United States" (虽然我们是页岩气资源大国,但我国页岩气开采难度大,成本高。这就意味着,我们不可能采取美国那样的开发方式).

Shale wells in Sichuan (home of China’s main shale plays) and Texas. Cherry-picked, yes, anecdotal, yes, but makes the geological difference a bit more visceral.

Other barriers exist, including a lack of natural gas infrastructure and imperfect legal/policy frameworks, and China has been working to address those issues.1 But the fundamental issue remains the economics and geology at the well — if it was cheaper to extract, China could rapidly expand their natural gas infrastructure, just as the U.S. did in the decade after 2005. But that seems unlikely anytime soon.

But that hasn’t stopped Beijing from announcing ambitious targets for fracking. In 2018, the Chinese Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation introduced a preferential tax policy to reduce the resource tax on shale gas production to 4.2% from 6.0%, which in 2023 was extended through December 2027. Following the release of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan in 2021, policy directives continued to support the development of unconventional natural gas resources, including adjustments made to the pipeline tariffs last year, and a new subsidy policy released just this month that incentivizes higher production.

Rather than hoping for a shale revolution, Guo Tonglou’s aspirations for Chinese shale gas are modest — he’s optimistic that, with more technical breakthroughs, shale gas could account for ⅓ to ½ of Chinese natural gas production. That would be an increase of their current production from shale from 25 bcm to 100-200 bcm annually, or from ~0.6% to ~ 2-4%2 of China’s overall energy. In contrast, the U.S. produced 836 bcm3 of natural gas from shale formations last year, which could provide around 30% of the U.S. overall energy.

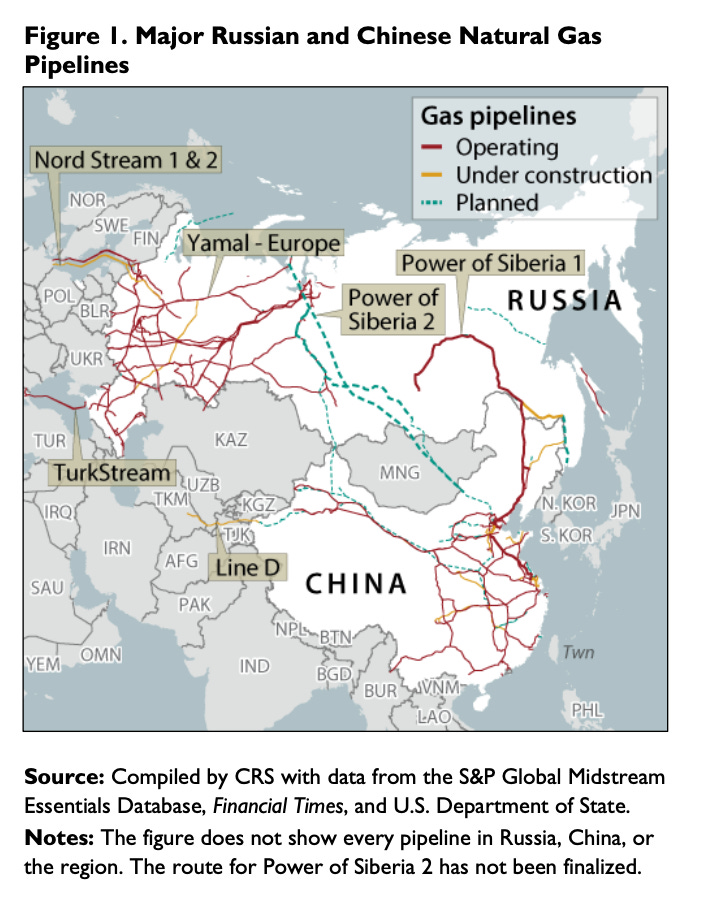

But is the juice really worth the squeeze? With a comparative advantage in renewables and coal, why invest in such a difficult domestic energy source? As one CRS report estimates, China’s demand for gas through 2030 can be met under existing contracts, and demand through 2040 can be met without having to increase trade with Western suppliers.

Economically, it doesn’t seem to make much sense. But in the age of great power competition, economics are no longer the primary concern — security is. And as the world’s largest importer of LNG, China has valid concerns. Shale will likely never reach the scale in China that it did in the U.S. But until China feels totally secure in its energy supply, its development will continue.

Chinese is Hard, Even for Natives

Moly from Chinese Doom Scroll reports:

Question: “Why does the 8th line on the Chengdu subway have an announcement reminding people to not bite fellow passengers?” [撕咬 — sīyǎo, to bite.]

A response from Chengdu Subway’s official account: “Uh! Sweetie. The subway is saying, ‘Do not broadcast noise from electronic devices to annoy fellow passengers.’ [滋扰 — zīrǎo, to annoy. In local dialect, it might be pronounced very similarly, I have no idea.] Create a civilised city, be a civilised citizen. The subway invites you to travel in a civilised way.”

“Not only are you not allowed to bite fellow passengers, you also have to be careful of the spy between the train and the platform.” [“Spy” “奸细” jiānxi here sounds like “gap” “间隙” jiànxì]

“I’ve also wondered forever why Chengdu’s East Station bans Cadillacs. [凯迪拉克— Kǎi dí lā kè] Does it actually mean something?”

“Are you sure it’s not, ‘No solicitations?’” [喊客拉客—hǎn kè lā kè]

“Shanghai buses play announcements, ‘Please dance when the door opens.’ It’s very confusing.”

“‘Please be careful as the doors open.’ They should also broadcast the same thing in Shanghaiese.”

“I came to Shenzhen for uni and heard the subway broadcast, ‘Watch out for kasayas,’ [袈裟 — jiā shā] And thought it meant to watch out for scammer monks or something.”

“So what was it actually?”

“To avoid getting pinched? [夹伤 — jiā shāng] Probably?”

“It’s okay, at least it’s better than the Shanghai subway. The announcement there is, ‘No bathing, performing, social, San Francisco.’”

“Huh? So what the hell is it talking about?”

“No begging, performing, selling, or passing out ads.”

“So what does, ‘Please go through the fried chicken passage.’ mean?” [炸鸡 — zhájī]

“Go through the turnstiles.” [闸机 — zhájī]

“There’s a minnan dialect announcement that just goes Lou Cha Lou Cha endlessly…”

“Lou Cha means depart hahahahahaha”

“Our maths teacher: Do not bite the classroom.” [干咬 — gānyǎo. I’m pretty sure it was supposed to be 干扰 — gānrǎo, disrupt the classroom.]

“The Beijing subway told me to not use yellow corpses.”

“Then I figured out it meant, ‘Do not use child leashes.’”

“One time, I was passing by an intersection and heard someone calling out, ‘Crazy~ Bread rolls~ Crazy~ Bread rolls~’ And I was like, ‘Just how crazy can bread rolls get? I gotta check it out!’ So I turned the corner to see the sign on the car, ‘Honey bread rolls.’ Someone was just calling out ‘Honey~ Bread rolls~’ with a dialect.”

“I’m the only one here with a straight answer. Biting is too cruel. We don’t engage in such inhumane methods. We usually prefer to swallow whole.”

For example, in 2011 China’s State Council approved changing the legal status of shale gas from a “natural resource” to an “independent mining resource,” which expanded private companies access.

Bidding opportunities went from being closed to foreign entities, to encouraging joint ventures.

In 2014, China’s National Development and Reform Commission issued a new policy that requires that pipeline operators “provide unused pipeline capacity to new customers on a fair and nondiscriminatory basis,” making it easier for natural gas operations to gain access.

Natural gas makes up about 8% of China’s energy supply, at 394.5 bcm. About 59% of that, or 232.4 bcm, is produced domestically. 25 bcm, or 11%, came from shale gas.

Assuming:

National energy consumption remains constant, with 8%/394.5 bcm = 0.0203 %/bcm representing the conversion from bcm of natural gas to percentage of China’s overall energy

Other sources of natural gas (currently 207 bcm) remain constant

Shale gas rises to constitute half of domestic production (thus also reaching 207 bcm)

Shale gas would then be 207 bcm * 0.0203%/bcm = 4.2% of China’s overall energy. If instead it was ⅓ of domestic production, that would be 104 bcm * 0.0203%/bcm = 2.1% of China’s overall energy.

In 2023, about 78% of total U.S. dry natural gas production (37.87 trillion cubic feet = 1,072.4 Bcm) was from shale formations. Thus shale gas = 1072 * 0.78 = 836 bcm. The U.S. is a net exporter of natural gas, which makes percent of overall energy from shale gas calculations more challenging. But as a back of the envelope calculation, with 38% of energy from natural gas, and 78% of natural gas from shale, shale provides roughly 30% of the U.S. energy.

why does China always get a free pass from you liberals? In everything. If you really cared about the environment like you like to signal, China is the most tragic case of polluting in the world. While making and selling solar panels, EV's, and wind stuff to the west! lol you're all crazy.

Carney - neo con Bilderberg Davos WEF elite who is globalizations poster boy. Isn't it weird this guy jumps from private equity at Goldmans and others (wow another banker who becomes head of primary bank of a country from Goldmans?!) Canadian Prime Bank president (just in time as Bernanke was for the great financial crash of 07/08) to directly be England's Bank president, back to the private equity world (of course this whole time be involved with WEF, Bilderberg, BIS) then to Canadian Prime Minister without an election? lol funny

This guy scares the hell out of me!