ChinaEconTalk: Huawei Will Die Without American IP; Why Amazon Failed in China

I’m Jordan Schneider, the host of SupChina’s ChinaEconTalk podcast. In this newsletter, I translate articles from Chinese media about tech, business, and political economy. If you reply to this email I will read and respond!

In the wake of the US Department of Commerce’s pronouncements on Huawei, the company has sought to project confidence. In public, Huawei said that it long been planning for the day when the US would limit its access to western technology by stockpiling chips and developing “spare tire” parts in house, and that its reserves will mitigate restrictions.

This claim is disputed by an anonymous author claiming to be a former high level Huawei research division employee. A short article published May 24, translated below, was pulled from WeChat shortly after going viral, but lives on the pages of less scrupulous Chinese websites.

Huawei high level worker: regarding ‘spare tire’ chips, there’s no chance

S深员工:关于备胎芯片,没有想象中美好, published anonymously, 5/24/2019

There are several departments that specialize in “spare tires.” For example, though Huawei is using Android, it is also developing a mobile OS. [At first] I didn’t understand why. Being big just for the sake of it isn’t that efficient. Modern technology is a product of companies’ specialization of labor…colleagues in these ‘spare tire’ departments don’t have future prospects, aren’t very efficient, and receive lower bonuses—naturally, people lose their peace of mind at work and you can imagine how their work product suffers.

Afterwards I realized that Ren Zhengfei knew “Imperialism” [i.e. America] and Huawei can’t piss in the same pot. After seeing ZTE’s situation, Huawei started getting prepared. Anyway, Chinese labor is cheap, it’s human wave tactics; you can throw a wide net and maybe end up catching a big fish.

The author goes on to argue that “good enough” tech doesn’t work in today’s environment:

First you need an environment, or what we would refer to as an ecosystem. You need upstream and downstream product support, and a ton of users. If your products are full of bugs, no users will have the patience for you and spend money on your stuff…

Chip manufacturing includes instruction set architecture and other design patents, test equipment, and tools, such as Godson’s MIPS command architecture and the ARM command architecture on Android phones. These require authorization and licenses from foreign manufacturers.

You can spend five years making your own command architecture and not relying on others. But if no one else follows your playbook, your ecosystem won’t develop, the upstream and downstream (compilers, operating systems, chip solutions, terminals, applications, etc.) won’t get developed, and eventually you will arrive at a dead end.” A similar example is China’s alternative 3G architecture TD-CDMA [which had no global takers].

What’s more, a lot of application chips are just hardware implementations of computing architectures and computing algorithms. Most architectures and algorithms in China don’t have their own IP and require authorization and licencing from foreign manufacturers…CCTV says 100% of them are Chinese intellectual property, but this is total bullshit.

I carefully read the recent letters Huawei leadership sent to its staff. As soon as I saw it, I knew it was classic Huawei. “In the desolate night a hero goes out to battle, never to return” [风萧萧兮易水寒,壮士出征兮不复还—a like from Han Dynasty century poetry describing a desperate mission], like when you’re walking outside alone at night, whistling loudly, to give yourself confidence. But in particular with regards to HiSilicon, the semiconductor company, according to industry insiders, this is totally ridiculous, “injecting chicken blood” [getting hyped up over something trivial].

For a company like Huawei that uses a lot of general purpose chips, breaking off access right away means the company will be totally screwed. HiSilicon doesn’t have the slightest possibility of meeting the needs of Huawei’s complete product line. They couldn’t even design half the needed chips. [All these chips that Huawei uses in its products] are like air; even though usually you barely notice it’s even there, as soon as it’s gone, you start choking to death.

Therefore, if the US breaks off access (by the way, the US accounts for over 80% of the world’s high end chips) Huawei only has a 1% chance of survival. Oh, and that’s not even factoring in that the US has a near monopoly on the software used to design chips.

Ren Zhengfei wants to independently develop all the chips, software, and an operating system. To achieve this demands a miracle of the scale never seen before in the history of mankind.

Good luck with that, Huawei!

Huawei CEO Ren Zhengfei, who like most Chinese of a certain age is a little too into Jews

Last month Amazon announced an unceremonious retreat from the Chinese market. In 2009, Amazon made up a respectable 15% of the Chinese e-commerce market. Yet the latest market reports put Amazon only at 0.6%. So what led Amazon, which has had considerable success in other overseas markets, to fail in China?

In a longform analysis published in Southern Weekend, journalist Zhang Yue interviews a number of current and former Amazon China employees for an inside take on its failure.

Amazon China, not enough ‘China’?

亚马逊中国,太不“中国”?Zhang Yue, Southern Weekend 4/25/2019

Product Issues

One employee, a seven-year Amazon veteran who requested anonymity, described the early days:

There was only one price and no discount system, so merchants who wanted to discount products had to change the price. But in China’s e-commerce, discounts are the norm—Alibaba’s discount system is at the “university level,” with clear documentation; JD is at the “high school level”; Amazon is at “kindergarten level,”and even once Amazon implemented discounts, many bugs remained.

Amazon had telephone and online customer service, but you had to dig to find it. Further, on Amazon, you have to leave a message and wait for a reply, which is quite primitive compared with Taobao and JD’s 24-hour online customer service.

Elsewhere on the product side, Zhang wrote, Amazon failed to adapt to market expectations. According to one former employee:

Amazon’s interface is globally unified, as they hoped that people around the world could operate on the same system without barriers. But compared with domestic e-commerce, its interface is just ugly.

Amazon requires that only the goods themselves can be displayed in the main picture of the product. For instance, if you’re selling a hair dryer, the picture can only display the hair dryer, and can’t show models or wigs. Amazon feels that this prevents marketing illusions. However, domestic consumers don’t agree, and because this internal policy persists, there’s no way Amazon can keep up with the livestreaming e-commerce trend.

The front-end of foreign e-commerce is not particularly friendly, but Amazon has done more to make its back-end very powerful, and does not make mistakes in data storage and user information confidentiality. Many domestic e-commerce companies are the opposite: the front end is very beautiful, and the back-end is a mess as many things are handled manually.

Management Challenges

Amazon also lacked a coherent strategy, squandering initial advantages.

It entered the market with the arrogance of a king (王者棋牌), which had advantages in books, mother- and child-related goods [e.g., formula and baby toys], shoes, bags, sports/outdoor and books. The book lead came out of its initial acquisition of domestic firm Joyo. The maternal and child sector leads came from imported brands. Amazon’s athletic shoe business was once the internet’s largest, as they offered both authentic and cheap goods.

However, all of these initial advantages have been squandered. Today, Ali and JD.com are giants, and each individual market segment has a well-known platform. Amazon seems to have only the Kindle.

Zhang pins part of the blame on leadership turnover. Over its 15 years operating in China, Amazon has run through four different CEOs, including two foreigners with no China background to speak of. The two Chinese CEOs had spent their careers in multinational firms. One former employee said:

Foreign internet companies have a hard time in China partly because they are too timid and under no circumstances play in the grey area. In terms of government relations and media relations, they are far behind domestic players.

Zhang also notes a vast gap in work culture between Amazon China and local competitors Alibaba and JD. Amazon has a smaller workforce (around 2,000) than its local competitors, and can’t afford to waste manpower. In contrast, Alibaba’s divisions often have overlapping responsibilities, leading to multiple teams working on similar projects. One former employee said: “If you believe e-commerce is a battlefield, Ali, JD and Pinduoduo are fighting every day. Amazon just has no fight in it.”

Amazon China employees told Zhang that they worked eight-hour days from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., and people felt comfortable taking doctor’s appointments in the daytime or picking up their kids from school. One ex-Amazon employee who currently works at Alibaba said:

Amazon really, really respects its employees’ personal time. Even when he had to occasionally work overtime, the boss would feel ashamed in asking their employees to do so, in contrast to domestic firms that commonly schedule meetings at 7 p.m. and believe employees owe them overtime as a seigneurial right and have brainwashed their employees into thinking “work is life.”

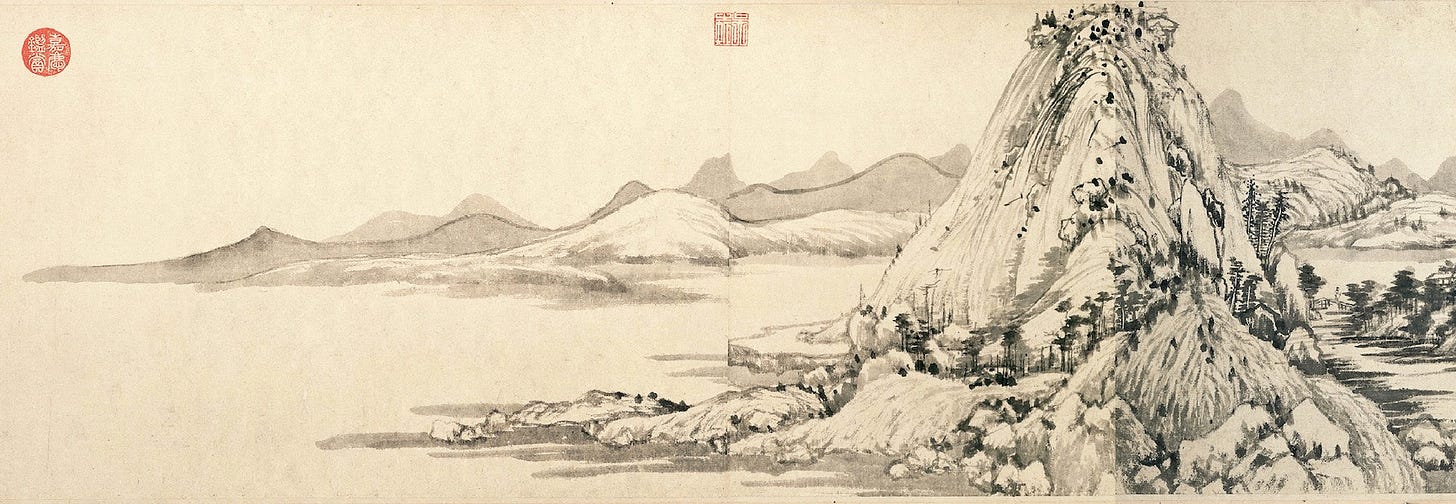

Landscape Painting of the Week

Huang Gongwang, one of the four Yuan Dynasty masters, was a prodigy scholar and at an early age passed the imperial examination. However, he was accused of corruption, lost his position, and became a wandering Taoist monk for this next 50 years. This masterwork, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, he painted when he was around 80. Legend has it he wanted it to burn with him as he died, but one of his sons secretly substituted it for another scroll (you can see burn marks above). Most of the scroll is in Taipei while the segment above is in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum.