ChinaEconTalk: Suzhou Soft-Serve, Smartphone KTV Battles, China's take on HBO's 'Silicon Valley'

Also featuring WeChat from Medium to battle Bytedance and Tencent vs Alibaba in Southeast Asia

This Week’s Podcast: The Rise and Fall of a Suzhou Soft-Serve Baron

Mister Softee, America’s famous ice cream trucks, in Suzhou, China? Yep, that was a thing. Turner Sparks, rising from humble beginnings as just another English teacher, achieved fame and fortune on the back of a catchy jingle and some mango-flavored soft serve. Yet his vision of China-wide ice cream domination dissolved amid a deluge of backstabbing regulators, slashed tires, and stolen waffle cones. Listen here on iTunes or Stitcher to hear from Turner the circumstances that finally melted Turner’s ice cream dream. The episode also features Athena Cao, consumer-focused investor based in Beijing, for broader context on what it would’ve taken to succeed.

Join our WeChat group here!

I have a confession: I don’t really like the name ChinaEconTalk for this newsletter. So today I’m announcing a Taobao T-Shirt Contest Giveaway! If you respond to this email with a new name for this newsletter than ChinaEconTalk that I go on to choose, I’ll personally pick out and mail you a free Taobao t-shirt. Because as we all know…

‘Music Meetup’—China’s Latest App Addiction

音遇, which doesn’t have an official English name, translates literally to Music Meetup. In just over three months, this app has garnered daily average user numbers in the millions and made a home at the top of App Store charts.

Here’s how it works: six strangers come together in a room where, after hearing a short clip of user-sung versions of hit songs (a clever sidestep of IP issues), they have to sing the succeeding verse. A forgiving AI then gives a thumbs up or down based on your performance, and over the next 10 minutes, crowns a winner. There are also ways to send fellow players gifts and level up on a leaderboard.

Here’s a clip where the AI cuts a child (and, ahem, your correspondent, at the 1:19 mark) down to size:

The fun comes from not just singing your KTV favorites, but the interaction in the virtual space. Players forget the lines halfway through, make up their own versions to the lyrics, get interrupted by their coworkers or parents. The atmosphere of these instant friend groups is in my experience a surprisingly cheerful and positive one, with little to no trolling to be found.

Given the imprecision of the AI judge, I don’t think this will ever evolve into something people pour hours and hours into ala 王者荣耀, Tencent’s enormous League of Legends clone for mobile. However, I’d argue that the development of this app has changed social norms in a way that gives those with stage fright — and screechy voices — license to belt away in public places.

I’m of two minds as to this app’s potential in the West. On the one hand, it’s fun as hell. Who wouldn’t want to break up their day belting out 15 seconds of Kelly Clarkson in the backseat of a car? But singing is much more normalized in China, and I wouldn’t be surprised if trolling was more of a problem in the West.

Other permutations of this model could prove interesting however. What if an app created a temporary space to debate politics, or the merits of one rapper over another? How about an instant place to cypher?

Here are two stories from the Chinese internet that delve deeper into this phenomenon:

2018’s Final Dark Horse: ‘Music Meetup’

2018最后一匹黑马“音遇”

Written by Yinzi Xuan 尹子璇, published on 猎云网 (Hunting Cloud), December 31, 2018

A Deep Analysis of ‘Music Meetup’

深度分析音遇

Written by Song Wenqun 宋文群, Tencent employee, self-published on December 4, 2018

Yinzi Xuan, author of the top link, argues that the app’s appeal comes from combining “singing, dating, and competitive games,” giving you a sense that you’re in a KTV room with strangers.

“Music Meetup” is founded by former Bytedance employees and has received significant investment from Bytedance. It shows many hallmarks of a Bytedance app: like Tik Tok, it deemphasizes social features in favor of entertainment. However, the app’s role in the “Bytedance-Tencent war for attention,” as Yinzi Xuan puts it, is murky, as one of the employees acknowledged to Xuan that Tencent is also involved in some mysterious way.

Song Wenqun is relatively bearish on the app’s potential for future growth. He finds the gameplay loop relatively shallow in comparison to megahits like PUBG Mobile and Honor of Kings. Further, the fact that you have to have the courage to sing out loud puts a ceiling on the type of people who will interact, and restricts gameplay times. The office worker on lunch break or with five minutes to spare on the toilet isn’t necessarily going to fire up a rousing rendition of Hou Lai 后来.

WeChat’s ‘clique-level algorithm,’ finally a way to do battle with ByteDance

微信「圈层算法」,终于有了和今日头条一战的可能

Written by Zhou Tian 周天 on his self-named 周天财经 — Zhou Tian Finance channel

December 21, 2018

Thanks to WeChat’s new “have a look” feature (看一看 kàn yī kàn) — called “Top Stories” in its English version — our job here at China Business Corner has gotten a whole lot easier.

Whereas Bytedance has deemphasized social sharing in favor of relying on algorithms, prior to this new release, WeChat followed more of a circa-2013 Facebook or Twitter model in that it presented content to users chronologically while doing relatively little to prioritize one’s closest friends or best content. With the addition of Top Stories, WeChat is supplementing this method with, as the author calls it, “scent matching,’ the ‘human algorithm’ of ‘people sorting themselves independently’ that I’ll tentatively call ‘friend circle-level algorithms.’”

In the past, the only two ways that someone could interact with a WeChat article were by forwarding it directly to a friend or using a cumbersome process to post it to your Moments. Moments are similar to Facebook’s News Feed but filled mostly with Instagram-style content from friends curating their lives. Active users are split into two camps: those who are selective about their posts and those who spam their followers with poor-quality content.

But now, after reading an article, a user can press 好看 (hǎokàn), i.e., “looking good.”

The closest analogy I can come up with, and perhaps the feature’s inspiration, is the “clap” button seen at the end of Medium posts.

This mechanism for interaction powers a new page separate from both one’s WeChat subscriptions (like a Twitter feed but only for brands and news outlets) and Moments (filled with Instagram-type content from friends alongside articles they think important enough to share), where the user can find articles that friends have liked.

Allen Zhang, the legendary creator of WeChat and China’s most famous product person, has long minimized the influence of AI on his product in favor of friend-driven curation. This new “take a look” feature is one of the many additions to WeChat in the recent 7.0 release which nods to the trends of the age while still taking advantage of WeChat’s dominance in social to drive user engagement.

How to view ‘Entrepreneurial Age’

创业时代怎么看

Published anonymously on “Sir电影” (Sir Movie)

October 26, 2018

When I first got to China, I asked around as to what TV show was closest to HBO’s Silicon Valley to practice my language and get a sense of Chinese tech culture. While lots of folks had seen the US show, none could come up with a suitable mainland analog. Sensing a market opportunity, I started jotting down stories and hunting for a co-writer, but ended up losing interest in this project after enough people told me I could never get something satirical produced.

In 2018, two long dramas about investing and tech came. One, The Golden Investor 金牌投资人’s first few episodes were so terrible feel a little guilty even giving you a YouTube link (no subs). Yet Entrepreneurial Age (创业时代 ), a 54-episode TV drama available here on YouTube (also no subs), I think has gotten a bad rap. With hated megastar Angelababy starring and legions of programmers decrying the show’s inaccuracies, Entrepreneurial Age has an atrocious 3.7/10 rating on Douban (China’s user-sourced Metacritic). However, this article by “Sir Movie” attempts to give the show a bit of context and revive its reputation.

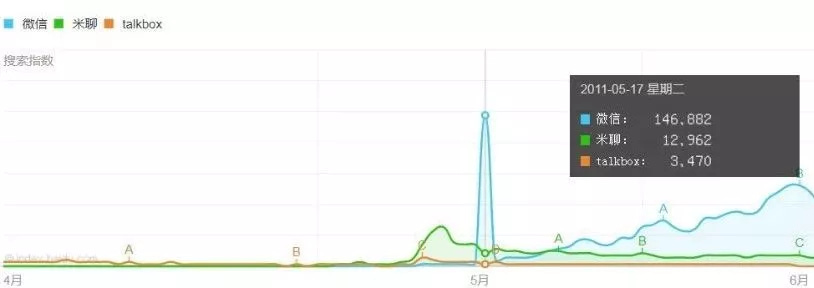

The central conflict in the show, a fight between two messaging apps, is based off a true tech battle that took place in 2010-2011. In real life, Hongkonger Guo Bingxin, frustrated at the inconvenience of having to look at text messages while driving, founded Talkbox. His messaging app prominently featured voice memos, a feature particularly useful given the difficulty involved in typing in Chinese. For a time, it seemed like his app could give the likes of not only WeChat, domestically, but also WhatsApp, internationally, a run for their money. However, WeChat’s May 2011 addition of a voice memo feature made TalkBox obsolete.

Baidu Search Index data from May to June 2011. The blue line is WeChat, the green is Xiaomi’s chat app, and the orange is TalkBox.

The show’s theme, this article argues, is that in today’s harsh “entrepreneurial age,” the best programmers don’t make the best founders. Beautiful coding and product innovation aren’t enough to guarantee success. More important is the ability to be presentable at meetings (the protagonist’s adversary “uses pick-up artist tactics to seduce investors”) and the gall to shamelessly copy competitors.

The review concludes: “This is the paradox of Entrepreneurial Age. We are all now witnessing how everyone’s life is being transformed by the innovation brought on by the internet. Yet when we try to have a taste of what the life of an internet legend is actually like, we realize it’s just so-so.”

Alibaba and Tencent copy and pasting their cashless game to Southeast Asia

阿里腾讯们在东南亚的复制粘贴游戏

Written by Liu Ran 刘然, published on 虎嗅 (Huxiu)

January 6, 2019

In America’s Asian grocery stories, the green sign for WeChat Pay (developed by Tencent) and the blue sign for Alipay (developed by Alibaba) have grown ubiquitous. But this article from Huxiu explores how it’s not only the US that’s in Tencent and Alibaba’s sights. Southeast Asia now is growing into the next great Alibaba vs. Tencent battlefield.

Why southeast Asia? The author believes that southeast Asia has a large population with a considerably high proportion of young people and ethnic Chinese. In addition, the market is close to mainland China, which makes it affordable for Chinese tech giants to set up shop there.

Both Alibaba and Tencent have brought their cashless battle to southeast Asia. And how’s it going? According to this article, the largest online merchant in the area, Lazada. Tencent expanded its business empire by acquiring or partnering with the likes of Sea Group, Go-Jek, Travelok, Pomelo Fashion, and Tiki.vn.

However, Alibaba and Tencent’s copy-and-paste game is being challenged by local governments that restrict business-to-customer and customer-to-customer transactions. Meanwhile, international companies such as RazerPay have also proven to be powerful competitors.

——————————————————————————————————————

If you reply to this email I will respond! Let me know if you’re more interested in more product converge like a deeper analysis of the new WeChat update, culture-type stories like Entrepreneurship Age, business-level analysis, macroeconomic stories, or what have you.