Fallout from the Think Tank–Driven Information Crackdown

Jordan: Over the past few weeks, global China-focused research organizations have had trouble re-upping their subscriptions to popular data providers like WIND (economic data), QiChaCha (China’s Crunchbase) and CNKI (JSTOR for Chinese academia). The great Lingling Wei of The Wall Street Journal reported this week that civ-mil fusion, PLA semiconductor acquisition, and Thousand Talents research coming out of prominent DC think tanks helped accelerate this trend:

The wider scope of the campaign is intended to ensure the party-state’s control over narratives about China. The part of it focused on restricting overseas access to databases began in earnest after some reports based on publicly available information set off alarms among senior Chinese officials, according to the people with knowledge of the matter.

The reports, these people said, included analyses written by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University and the Center for a New American Security, co-founded by Kurt Campbell, the White House’s coordinator for the Indo-Pacific.

Using open-source data, several of the reports focused on areas that Beijing considers sensitive, such as what it calls civil-military fusion—the interplay between China’s civilian research and commercial sectors and its defense sector to advance the country’s military capabilities…

Some Chinese officials say several Washington-based think tanks have mined the country’s open-source data to help validate a hard-line U.S. policy toward China, such as heightened restrictions on the sale of high-tech products to Chinese companies.

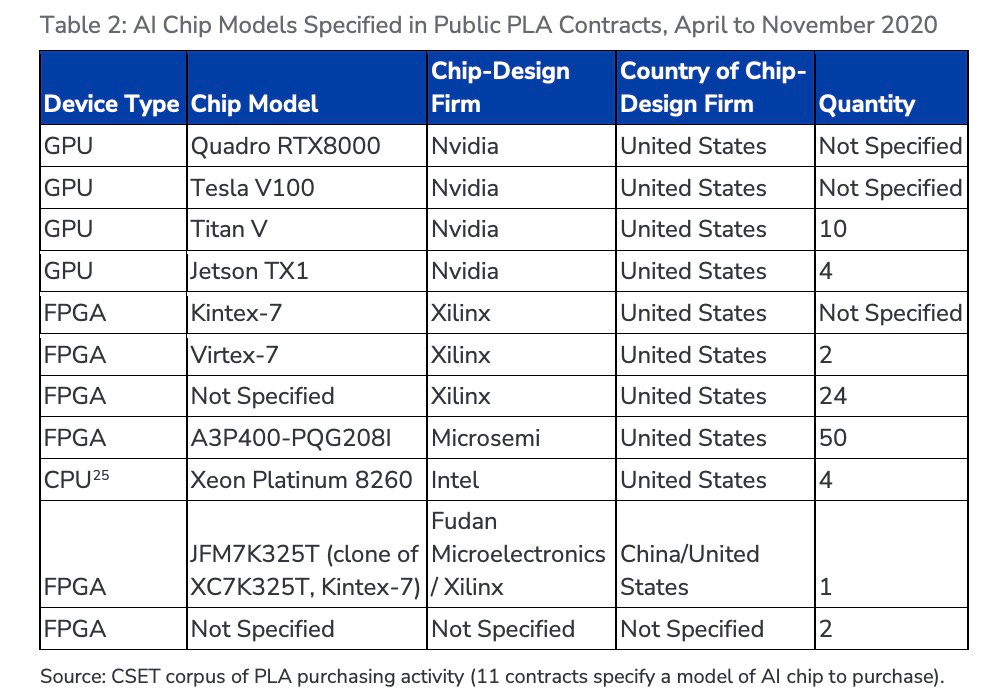

One of the U.S. think tank reports that got Chinese authorities’ attention, according to the people, is a policy brief published by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology in June, titled “Silicon Twist.” It focuses on Chinese military access to advanced chips designed by American companies and manufactured in Taiwan and South Korea.

Also on Beijing’s radar, said the people who have consulted with Chinese authorities, is a catalog compiled by the center for Chinese initiatives aimed at recruiting scholars and students in support of China’s strategic goals, called “The Chinese Talent Program Tracker.”…

The Cyberspace Administration of China, an agency set up by Chinese leader Xi Jinping to police the internet, in March notified various Chinese data providers to restrict overseas access to information involving corporate-registration information, patents, procurement documents, academic journals and official statistical yearbooks, said the people who have consulted with Chinese authorities…

Some publications by the Center for a New American Security, according to the people, have rattled China’s leadership, including 2019 testimony made by a senior fellow at the center to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a group Congress has charged with providing policy recommendations based on its evaluation of national security and trading risks associated with China.

At least these “senior officials” have good taste in research. It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of CSET (after all, they’re the winners of ChinaTalk’s inaugural Think Tank of the Year award). I’m also a fellow at CNAS. I want to take a moment to celebrate the authors of the papers for their scholarship.

Elsa Kania’s testimony on the PLA was a meticulous tour de force of qualitative research. She painstakingly read open-source documents to catalog branch by branch how the Chinese military was grappling with AI, painted a synthetic picture at both the tactical and strategic level of its potential future impact, and put forward policy recommendations that have stood the test of time. It’s a document I’ve repeatedly come back to in my own research — and I have recommended it to young scholars to inspire them about just how deeply you can add to the national discussion as a diligent, independent researcher with strong language skills.

Emily S. Weinstein’s Chinese Talent Program Tracker is a deeply sourced overview of a few dozen initiatives “aimed at cultivating China’s domestic talent pool in support of China’s strategic civilian and military goals.” Who knew that meteorologists had their own talent program!

Ryan Fedasiuk, Karson Elmgren, and Ellen Lu’s Silicon Twist is a rigorous data-driven deep dive into Chinese military procurement data which illustrated that — with some good scrapers, language skills, and elbow grease — you can learn an impressive amount about the PLA’s compute demands.

This trend will make it more difficult, but certainly by no means impossible, to make real contributions via open-source research on China. The Party and state will still need to disseminate information to a broad internal audience in order to govern effectively. There are underground services to get access to CNKI articles, just like there are for folks without university affiliations not particularly inclined to pay $40 to read a western journal article.

To be sure, open source research has driven embarrassing global coverage around sensitive topics like Xinjiang and civ-mil fusion. However, in the medium term I think this move will be counterproductive for many of Beijing’s core ambitions. Less transparency in this environment will only lead the media and policymakers to assume the worst as well as make both foreign and domestic investors to feel less confident in putting money to work in the PRC. The “information blackout risk premium” will be an interesting dynamic to track going forward.

Nicholas: This move comes amid an already steady roll of advocacy to bolster the US’s open-source collection capabilities:

An October 2022 SCSP report calls for a standalone open-source intelligence agency (the proposal was also publicized in The Hill and Foreign Affairs).

Dennis Wilder on ChinaTalk lamented that the CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) was closed in 2005, and urged its reinstatement.

And some have done more than just call for change: Alison Killing of Bellingcat — a Netherlands-based open-source journalism group — published an excellent manual of sorts on confronting the challenges of open-source data collection in China.

Since the need for getting information about China isn’t going anywhere, this latest crackdown may help US policymakers overcome their bureaucratic inertia and more quickly heed those calls for better open-source capabilities. And if open source carries its weight in reestablishing US intelligence-gathering in China, the CCP leadership may not enjoy the long-term consequences of today’s data crackdown.

Irene: Another reason this crackdown may backfire: cutting access across the world — including in countries sympathetic or at least more neutral toward China — may offend otherwise friendly entities.

Per Lingling Wei’s report, it seems there are two ways that China is restricting the flow of information outward:

By preventing previous contracts with foreign organizations from being renewed;

By removing information from the open web altogether (as with CNKI).

The former approach — which mainly targets US-origin think tanks and consultancies seen by the Beijing as unfriendly — might give a temporary edge to China research done in non-US locales. If the tradeoff for access to information, however, is curtailing research aims according to Beijing’s preferences, Western institutions are unlikely to embrace the deal.

The latter approach, though, affects everyone. Making the black box darker is, in a way, a devil’s bargain: reducing trust and transparency will deal indiscriminate damage to a wide variety of relationships.

Irene—China’s First ChatGPT Crime

In what appears to be a first in China, someone has been detained for activities related to ChatGPT. Police in the northwestern Gansu province announced on May 7 that they have arrested a man surnamed Hong for “using artificial intelligence technology to concoct false and untrue information,” per Jiemian News 界面新闻 and the South China Morning Post. The man allegedly posted fake news surrounding a train crash to twenty-one Baidu accounts simultaneously. To bypass spam filters, he asked ChatGPT to write slightly different versions of the same story — which received more than 15,000 clicks before the posts were taken down. [Jordan: on WeChat, the threshold for considering something really viral is 100k…]

The legal aspects of the case are particularly notable given February’s “deep synthesis” regulations and the recent generative AI regulation draft. While news coverage of the case highlights the involvement of generative AI, Hong is actually being charged for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (PQPT), the classic catch-all crime frequently applied to anyone the regime sees as a nuisance. Perhaps this charge is related to the fact that ChatGPT in China is accessible only with a VPN, which means that Hong has definitely bypassed the Great Firewall. The use of ChatGPT could also affect the severity of Hong’s sentence, as generative AI arguably made his stories reach more people and create a bigger impact.

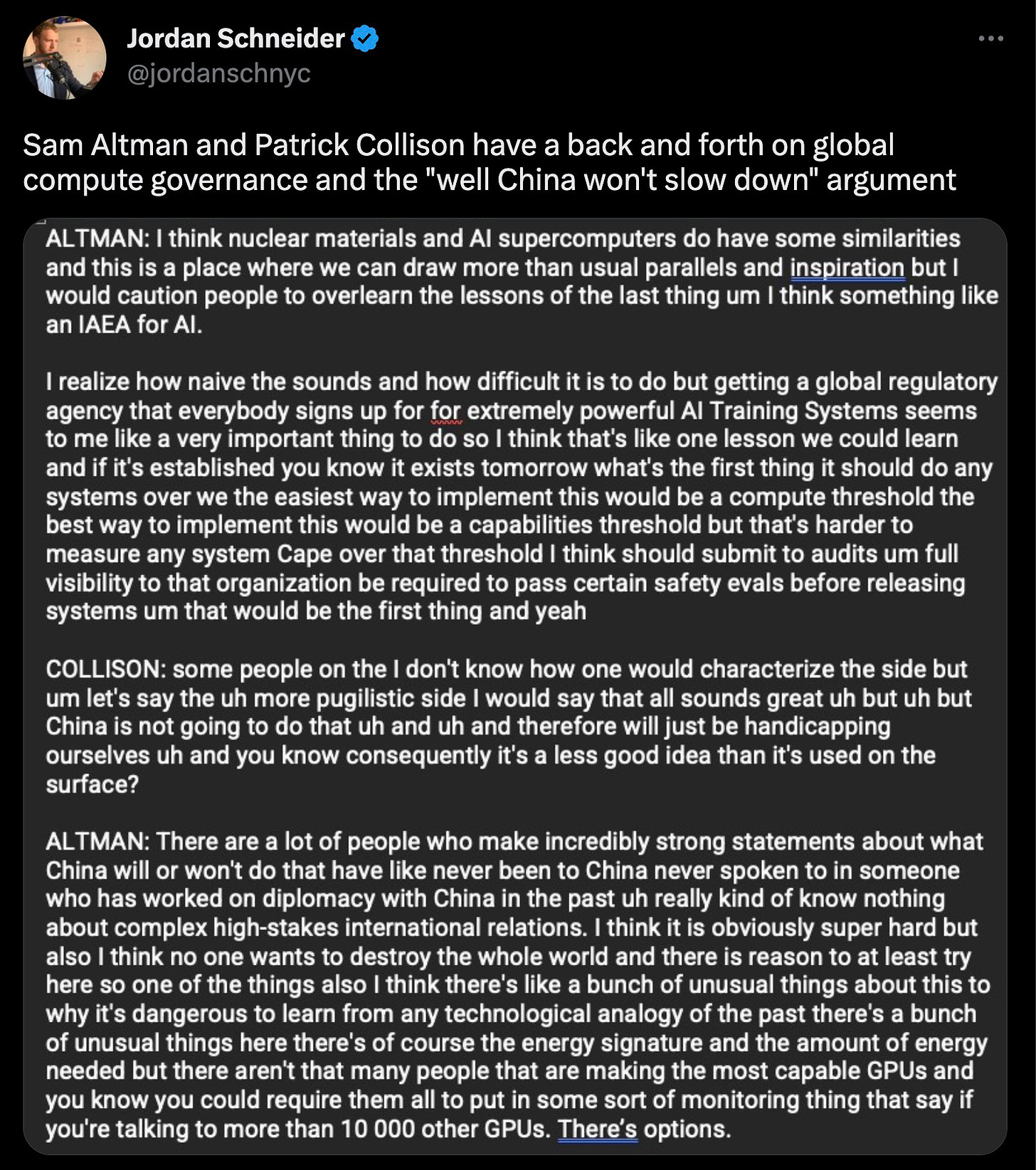

Some AI Tweets

Check out the ChinaTalk podcast! It’s really good!