China's Elite on Ukraine War Anniversary

"Most tragic is witnessing a nation that does not remember its past mistakes."

On the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, domestic discourse on the war remains divided in China. While state propaganda regurgitates Putin’s talking points and most independent commentary does not stray far off, it’s also not difficult to find writers and media personalities supportive of Ukraine. Some, however subtly, are also critical of Beijing’s relationship with Moscow. Below are some excerpts translated from Chinese media, including:

A Chinese nationalist’s case for supporting Ukraine;

Chinese academics’ assessment of European relations;

A State Council advisor’s warning;

Putin’s grave missteps;

The role of Belarus.

Chinese Experts on Economic Warfare

Yicai, a business media outlet based in Shanghai, gathered Chinese experts to respond to questions about the war and its economic impacts.

Q: It’s been a year since the Russia-Ukraine conflict began. Why did the war not end as quickly as Russia had expected?

Liu Jun (Executive Director of the Center for Russian Studies, East China Normal University): On the one hand, Western countries like the US have provided Ukraine with weapons and resources, which very quickly boosted Ukraine’s ability to resist. On the other hand, Russia underestimated its adversary; the fact that it replaced its top military leader three times shows that it underprepared in advance. In addition, negotiations are still unable to proceed. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is set to expand and turn sclerotic.

Q: What does Bakhmut mean for both sides? Why has Bakhmut become a focal point?

Wang Qiang (military affairs commentator): The first important reason is that its strategic location for transportation is significant. Conquering Bakhmut will mean that Russia can build up a totally thorough frontline from north to south. Additionally, from a political level conquering Bakhmut is significant for Russia’s consolidation of its military. From the Ukrainian perspective, Bakhmut is the best piece of leverage with which further Western support can be secured.

Q: Many Western countries applied comprehensive sanctions on Russia, but according to the IMF report Russia’s economy has not contracted as severely as expected. Why is that?

He Weiwen (Senior Research Fellow, Center for China & Globalization): One reason is that Western sanctions themselves have loopholes. The other is that Russia took relatively effective measures to stabilize its energy sector. Its sales of oil and gas has, in fact, increased; at the same time, it has stabilized exchange rates for the ruble and raised banks’ interest rates domestically to lower inflation. As a result, its overall economic situation was stabilized and reinforced.

Q: The ruble’s exchange rate is possibly even higher now than it was a year ago. Why is the ruble so strong?

Tan Yaling (President of China Foreign Exchange Investment Research Institute): First of all, Russia’s “ruble decree” means that the transactions for most of its imports and exports of oil, energy, and personal goods are likely conducted in rubles, which possibly leads to higher valuation of the ruble. Moreover, if we look at the basic economic foundation of the ruble, Russia’s status as an oil producer and rich natural gas resources means that it has confidence in maintaining control over Europe.

Q: Inflation in the Eurozone reached the highest point since 1997 last year. How has the Russia-Ukraine conflict affected Europe’s economy?

Wu Huiping (Deputy Director of the German Academic Center, Tongji University): Most European countries joined in on sanctioning Russia, which has affected their own economies. For example, Germany was originally highly reliant on Russian oil and gas. Over the past year, German ministers have been going around the world to sign natural gas supply agreements. There is also a severe increase in the costs of goods: Germany’s inflation rate in September reached 10%, which sets a post-war record. Excessively high costs of living and energy prices have raised the costs of production by a significant extent for European companies, which then lowers their competitiveness. Some predict that the German economy is set for a technical recession.

Q: What other impacts could the Russia-Ukraine conflict bring for Europe?

Xin Hua (Director of the Center for European Union Studies, Shanghai International Studies University): Multi-layered conflicts within the EU could be exacerbated. In addition to discord between France and Germany, another layer of conflict is that between Central and Eastern Europe and Western Europe. Central and Eastern Europe believes that Western Europe is unreliable, to the point where they sometimes circumvent Western Europe and the EU altogether in order to directly interact with the US. Divergence between Poland and core EU states is likely to grow. There is also a third layer, which is discordance among states like Italy, Spain, and Greece should their economies perform disappointingly. From above it looks like European states are united in their support of Ukraine, but this still reflects the exacerbation of multi-layered conflict underneath the surface.

Q: Currently, both sides of the conflict are able to withstand warfare quite well. When will the Russia-Ukraine conflict end?

Zhang Hong (Researcher at the Institute of Russian, Eastern European & Central Asian Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences): There is the possibility of either side changing course as result of domestic and international pressure. But evidently, this is currently impossible for Putin, Zelensky, or Biden. Our hopes currently lie in 2024, when so-called “political changes” may arrive. In my opinion, the conflict is likely to last throughout 2023, but turning points could come about in 2024.

A Pro-Ukraine Little Pink?

A current affairs blogger shared this on WeChat on February 24. It’s a fascinating, if niche, perspective: the language is straight out of Global Times or Guancha, but the author comes to a very different conclusion based on China’s history.

Since the beginning of the US-China trade war, the US, along with its allies, has applied extreme pressures on China. Because “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”, many fellow netizens have expressed genuine empathy towards Russia and shared solidarity with their grievances.

But there is a difference between understanding global power struggles and LARPing. While some Russian citizens are protesting the war in the streets, there are some in our own country who act more imperialistic than Tsarist Russia.

Let’s pull out the microscope and review some Russian moves that look a little familiar:

Russia demands that Ukraine acts as a buffer zone between itself and NATO. We remember the pain of Outer Mongolian independence. [Editor’s note: The idea that Mongolia should have remained a part of China is a view held by a fringe wing of Chinese nationalists.]

Russia manipulated eastern Ukraine into an independence referendum. We fix our own gaze upon a certain island in the southeast [Taiwan].

Russia boasts that it can use strategic nuclear weapons. We once feared that the USSR would threaten us with nuclear capabilities.

On the anniversary of the Russia-Ukraine war, we see that every single step Russia has taken so far lands on a painful point for China.

The US, in using its strengths to bully the weak, is a jackal; Russia, in its no-guardrails militarization, is a leopard.

When great powers compete, collateral damage is inevitable. But fellow netizens should not overly invest their own feelings and become complicit in the aggression of a violent tiger.

There is no such thing as permanent friendship between countries; there is only the permanent relevance of profit. During the US-Soviet Cold War, we once wholly supported the USSR, but after Zhenbao Island there was a US-China honeymoon.

As the international order transforms, one hopes we can proudly say in hindsight that we stood on the side of justice.

To whom does justice belong?

In October 2022, 143 countries denounced Russia’s illegal conquest at the UN. Only five countries supported Russia.

Wang Yi’s Dilemma

Hu Wei, vice-chairman of the Public Policy Research Center of the Counselor’s Office of the State Council, published a reflection on the one-year anniversary of the war on February 24. A year earlier, his piece warning that alignment with Russia would make China an international pariah was read more than 1.5 million times before being censored in China. The full piece was translated by the U.S.-China Perception Monitor. Here’s an excerpt:

Director Wang Yi arrived in Russia shortly after President Biden left Ukraine, highlighting the divergence between China and the U.S. on the matter. Earlier on February 18th, Wang Yi declared at the Munich Security Conference that China would publish a position paper on the first anniversary of the Ukraine crisis. Indeed, the Chinese Foreign Ministry published the document on the 24th with great fanfare. China’s effort to attract global attention to this document is evident. The position paper consists of 12 points, all of which consistently echoed China’s previous viewpoints on the Russo-Ukraine confrontation, including proposing a ceasefire, jumpstarting negotiation, and opposing the use or the threat to use nuclear weapons.

Yet the paper contains no specific implementation plan or any operational measures. Point 10 calls for removing unilateral sanctions and what it refers to is self-evident.

As such, nations in favor of imposing sanctions on Russia will not accept this document. Ukraine, of course, will not agree with the proposals. Even Russia says the document does not reflect its positions.

At this time, the battlefield momentum and the moral advantages are both in the hands of Ukrainians. To call for negotiation under this circumstance holds no realistic foundation. The publication of this document will not bring about any real impact on the progress of the Russo-Ukraine War, but it will have a huge impact on how China is going to position itself in the international community. As the prospect of the war gets clearer, China is in a dilemma with not much room to maneuver politically.

…No decision-makers can avoid making mistakes and the only difference between wise decision-makers and foolish ones is the ability to learn from past errors, reverse wrong policies in a timely manner, and stop the losses as early as possible. Russia as a nation-state has taken many detours in the past, yet the tuition it paid has resulted in nothing. At this juncture, the conclusion of the “Ode to Afang Palace” (an essay by the Tang Dynasty author Du Mu on what lessons to be learned from the collapse of the Qin Dynasty) appears in front of my eyes:

“The people of Qin were too busy to lament themselves. Later generations lamented the collapse of Qin but refused to learn the lessons. And they were doomed to be lamented by later generations.” ( 秦人不暇自哀,而后人哀之。后人哀之而不鉴之,亦使后人而复哀后人也。)

What is the most tragic is to witness a nation that does not remember its past mistakes.

Putin’s Mistakes

Zheng Yongnian, a prolific but controversial Chinese University of Hong Kong political scientist (who allegedly sexually assaulted students at NUS, among other things), wrote a long piece on February 24 arguing that the war is a proxy conflict between Russia and the United States. Among other assessments, he attempts to outline what Putin did wrong:

On the whole, Putin's mistake lies in different degrees of underestimation and overestimation of various internal and external factors.

In terms of external factors, first, he greatly underestimated the Zelensky government’s will to resist. Early in the war, Russia spread the news that Zelensky had left Kyiv. This was reminiscent of then-Afghan President Ghani's hasty flight after the Taliban triggered regime change in Afghanistan.

However, by posting a video on social media, Zelensky proved that he was still in Kyiv, thus stabilizing Ukraine's military and public confidence and laying the groundwork for a shift from Russia's "strategic offensive" phase to the "strategic standoff" phase of the war.

Second, Russia's strategic vision for Ukraine is too ambitious and does not limit "special military operations" to the Donbass region in eastern Ukraine.

If the conflict had been confined to the Donbass, Russia would have had a reasonable basis for calling it a "special military operation”.

However, Russia chose to strike on three fronts in the early stages of the war, expanding the scope of the "special military operation" and turning it into a war.

Third, Putin underestimated Europe's reaction. Europe reacted strongly to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and not only did not compromise under the threat of Russian "energy cut-off", but also provided strong support to Ukraine, especially to the "New Europe" countries led by Poland. Not only did EU member states achieve "unity" through war, but even Finland, Sweden and other countries abandoned their previous neutral positions.

Fourth, Putin underestimated the U.S.-led NATO.

Through this war, NATO continues to expand eastward and even provides security support to Ukraine, and has received an application for membership from Ukraine.

Since 2014, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine around the Donbass region has gradually "activated" NATO, suddenly reverting NATO’s "sense of loss" of strategic competition after the Cold War.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict raised the role of NATO to a level unseen since the Cold War. It was this underestimation of NATO that led to Russia's missteps in its pre-war assessment.

Internally, Putin overestimated Russia's overall strength. The fact that Putin's envisioned "special military operation" turned into a war is not unrelated to his overestimation of Russian military capabilities. Before the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, it was widely believed that the Russian army was still the second largest armed force in the world, although it was limited by the level of Russian military spending after the Cold War and could not be compared to the former Soviet Red Army.

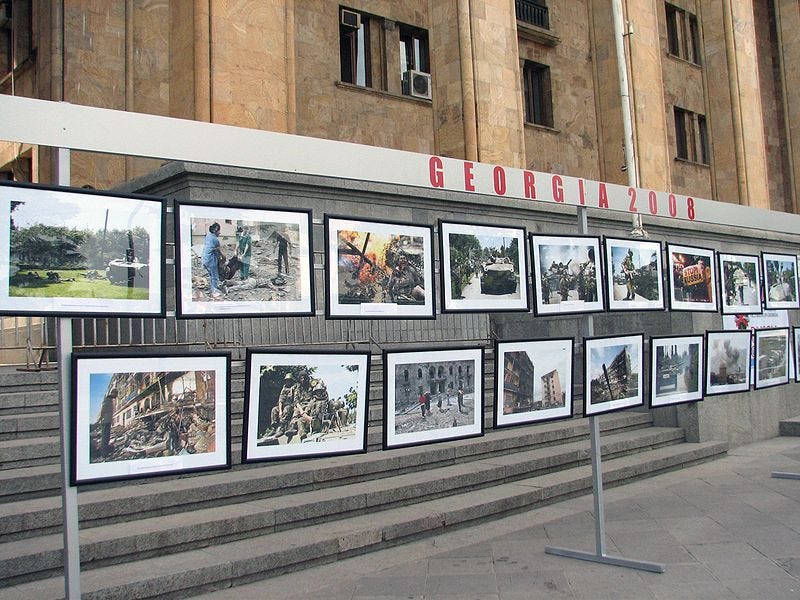

It can be argued that the Russian military had a certain deterrence capability after the Russian-Georgian war in 2008, Crimea's entry into Russia in 2014, and its intervention in the Syrian civil war in 2015. However, the Russian military's performance in the current war is far below general expectations. Russia's combined national power, under U.S. (Western) sanctions, can no longer support winning a high-intensity regional war.

Russia's ability to mobilize and the endurance of Russians were also overestimated. In September 2022, after Russia announced a "partial mobilization order," some Russians chose to flee to Russia's neighboring countries to avoid conscription. Although the term "anti-war" has become an open taboo in Russia, some Russians are still "voting with their feet," which has had the effect of reducing Russia's mobilization capacity.

Another group of Russians, unable to bear the impact of the war on their lives, transferred their assets in Russia by various means at self-service teller machines (ATMs) in European countries after Russia announced foreign exchange controls.

What About Belarus?

Phoenix Television, a marginally more liberal state-owned broadcaster with a strong Hong Kong presence, spoke to Chinese experts to hear their views on the conflict’s anniversary. Particularly interesting is the section on Belarus, given recent news that Xi is set to welcome Lukashenko in Beijing: