On Thursday, a fire in Urumqi, Xinjiang, apartment complex killed at least ten. Many on social media suspected that Covid Zero restrictions like iron-barred windows and roadblocks inhibited evacuation and firefighters’ access, contributing to an increase in casualties. The next day, largely Han protests in Urumqi numbering in the thousands gathered to express their outrage with current policies. At least 79 university campuses across China have seen protest actions, ranging from a sizable gathering at Tsinghua to graffiti at Beida. Friday and Saturday, thousands gathered in the streets of Shanghai, Beijing, Wuhan, Chengdu, Guangzhou and other cities, making various demands including the end to Covid Zero, freedom of expression and media, and even the fall of Xi Jinping and the CCP. The Inititum made a useful map illustrating the scale of the unrest and has more comprehensive coverage than anything I’ve seen in western media. If you can read Chinese, I’d encourage you to subscribe and support their work.

The protests seem to be a truly cross-class manifestation of anger, with educated youths and workers turning out across the country. The acute cause of this protest is frustration with Zero Covid. The policy has had both generalized and concentrated impacts. The western media has done a decent job of capturing the general impacts of reduced economic growth and day-to-day headaches around mask-wearing, testing, and travel restrictions. However, beyond these impacts, the policy has fallen disproportionately on the poor who need jobs to survive, those who’ve life savings have been lost due to family businesses destroyed by covid, and the countless who suffered through forced quarantines.

Protesters have not limited their demands to Covid restrictions alone. Videos are circulating of chants demanding freedom of expression, freedom for Uyghurs and even Xi’s ouster. Beyond Covid Zero, frustrations resulting from Xi’s increasingly autocratic governance are manifesting.

What happens from here?

In the short term, Xi has two decisions: how to handle Covid Zero and how severely to crack down on the street and online protests. The key unknown is just how much sustainable momentum there is behind the popular movement today, and how decisions around Covid policy and repression will impact public opinion and the intensity and scale of street protests.

How Hard Will the State Crack Down?

I would not underestimate the capacity of the Chinese security state to deal with medium or even large-scale domestic disturbances. For thirty years the Chinese state has been aggressively investing in state capacity to respond to these sorts of eventualities. The system looked like it was caught flat-footed over the weekend, with online censorship completely failing to control the narrative and policemen mostly standing by while protesters across the country demonstrated. However, I expect both online censorship and street-level government responses to be much more severe in the days to come.

First, the online domain. In past rounds of recent public outrage, like during the Li Wenliang saga in the early days of Covid, the censorship regime at first struggled to respond. Particularly over weekends, when many censors take off work, sensitive content seems to have a longer lifespan. Over this past weekend, obviously sensitive WeChat articles racked up millions of views and stayed online for hours upon hours. People were able to live stream protests on Douyin. There’s a small chance that censors, sympathetic to the protesters, have been “quiet quitting,” but more likely this is just a function of incompetence and layoffs that have been heavily impacting the consumer internet.

I expect in the coming days this state of affairs to change. Additional escalatory steps if regular heightened censorship doesn’t quiet things down and disrupt future in-person actions include shutting down WeChat Moments, deleting large WeChat groups that use any controversial language, shutting down Douban, and even going after Github. This seems to already be happening.

Now, turning to street protests. Over the past few days, we’ve seen a relatively lax attitude on the part of the police towards the protesters. For an example of how softly police are currently handling the situation, see the Economist’s David Rennie’s thread of a protest in Beijing where the police were handling the situation “cautiously.”

I don’t see a scenario where Xi tolerates continued street activity, particularly in key city centers like Beijing and Shanghai. Just in the past few hours we got a glimpse of what mobilization will look like, with some heavy duty “anti-terrorism” trucks (VN-4s?) apparently getting trucked into Shanghai overnight.

Escalatory moves the government will likely take include the use of tear gas in the event of larger or more unruly gatherings, an announcement of mandatory long prison sentences for protesters, and a freer hand in disappearing protesters off the street (which has already occurred sporadically).

It is in these police measures, not the online crackdown, where the small but real risk for the government lies. Past protest movements like those in Hong Kong gained momentum after violent police action galvanized fence-sitters into joining in-person movements.

Non-activist Han Chinese post-89 (setting the Falun Gong aside) have by and large not been subject to the sharp end of autocracy. Covid Zero measures have given people a strong taste. However, arbitrary, indefinite detention for hundreds if not thousands of youth and the excessive use of force shared widely on social media may change the calculus for the masses.

That said, it is unlikely that these protests metastasize into an ongoing concern attracting upwards of tens of thousands or stretching out months. Hong Kongers had multiple rounds of protests in the 2010s to learn and organize before the summer and fall of 2019. Small actions like the 2018 Jasic Factory unionization drive are a far cry from Occupy Central and the Umbrella Movement. Hong Kong also benefitted from secure communications on Signal and Telegram as well as a police force that in the initial weeks was both too soft in cracking down and too undisciplined not to create viral moments of violence. I’ve seen some posts on WeChat of folks ordering protester materiel like wirecutters on Taobao—Hong Kongers kept getting these sorts of things delivered far longer than mainland Chinese should expect to.

Overall, how skillfully the government directly cracks down on street and online protests will likely have a decisive impact on the trajectory of the movement. There are, however, edge cases where Beijing either comes out aggressively in favor of Covid Zero (20% in my estimate), inflaming tensions on the street, or announces an abrupt end to Covid Zero (5%). In the later case, it’s more likely that this will in the near term calm things down than embolden protesters to demand more concessions. However, if this announcement comes following weeks of increasingly intense street activity, then a Covid policy change could potentially embolden protesters. All that said, I don’t think Xi is the sort of leader who will want to look weak in the face of protests.

Whither Covid Zero

Many Chinese got their hopes up that after the Party Congress restrictions would ease. Despite some official movements towards easing we’ve still seen strict enforcement persist in much of the country. This is the classic Tocqueville Effect where a gap in expectations when already on a positive trajectory generates the most popular anger.

However, what the protests means for Covid Zero in the very near term is really anyone’s guess. Lifting Covid Zero would be a straightforward way to quickly a billion people less pissed off and allow the system to show that it is listening. But I wouldn’t put it completely past Xi, who has stuck with a counterproductive policy for this long, to keep it going just to prove a point. And people shouldn’t forget that what comes after Covid Zero is exceedingly grim.

“The level of immunity induced by the March 2022 vaccination campaign would be insufficient to prevent an Omicron wave that would result in exceeding critical care capacity with a projected intensive care unit peak demand of 15.6 times the existing capacity and causing approximately 1.55 million deaths.”

This paper was released in May, but even a million deaths is a really high number! The majority would be elderly,leaving tens of millions furious that a policy change led by the central government led to their relatives’ deaths.

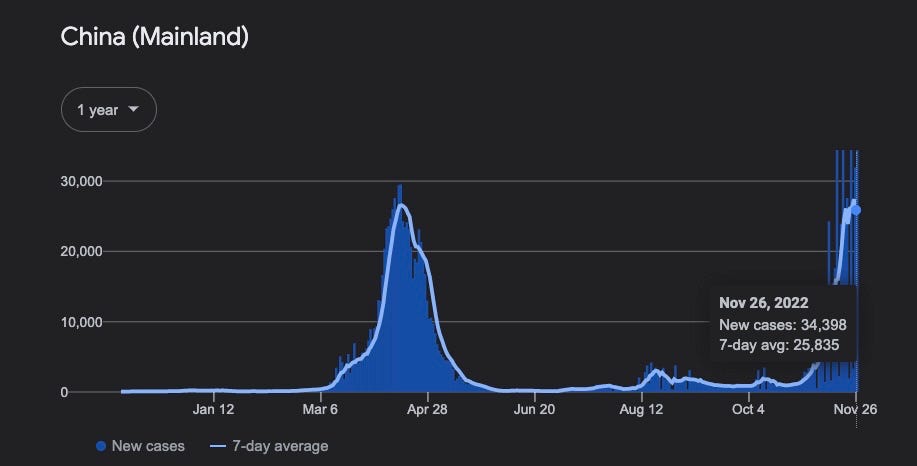

Uncontrolled exponential spread of Covid in the coming months may already be baked in. Yesterday China announced over thirty thousand new cases spread across the country, numbers not seen since the Shanghai outbreak in April. Deeply aggressive lockdowns of the sort required to get the virus under control in that instance seem beyond the political pale today. If so, expect a breakdown of testing capacity and the quarantine system with hospitals completely overwhelmed.

During and after this phase of rapid spread will come another major test for social stability. I doubt that in Covid Zero’s deadly aftermath people will be particularly sympathetic to government claims that they’re doing the best they can did the best they could in trying to prevent deaths as they fail to find hospital seats for their dying relatives.

On Elite Politics

I wholeheartedly agree with this point. Yes, there are some people high up in the party who aren’t entirely on board with the implementation of Zero Covid. Recall that even Li Qiang, the incoming Premier, tried to chart a more moderate course in Shanghai before being forced to lock the city down. However, disagreeing on Covid policy is a far, far cry from a Hu Yaobang or Zhao Ziyang. As Julian Gewirtz explores in his fantastic new history of China’s 1980s, there was a widespread movement for political reform in the 80s pervasive in civil society that had momentum even in the highest levels of the party. In the mid-80s even Deng was sending signals that he was on board with political reform. There is zero evidence for anything like that burbling in today’s leadership structure.

Into the medium term, we are far more likely to see Xi’s China trend more into militarized autocracy than use this moment as a reset point to pursue a more open and conciliatory policy.

Impact on China’s International Relations

I’ll close with some far-too-premature speculation on what the protests mean for the China’s relations with the world. Inevitably, the propaganda response will include assertions that the protests were part of a CIA plot with foreign black hands pulling the strings. It’s important not to forget that some high level Party leaders really do believe this stuff. See, for instance, Desmond Shum’s beat in his book Red Roulette about how Wang Qishan, a sophisticated technocrat with significant overseas experience and personal ties, loved a book that bought into anti-semitic conspiracies about global finance.

Wang also shared some of the paranoid delusions particular to China’s ruling elite. He was, for example, a huge fan of a 2007 best seller, Currency Wars, written by a financial pundit named Song Hongbing. Song claimed that international, and particularly American, financial markets were controlled by a clique of Jewish bankers who used currency manipulation to enrich themselves by first lending money in US dollars to developing nations and then shorting those countries’ currencies. Song’s book mixed the disdain, suspicion, and awe of the United States held by many of China’s leaders. Wang Qishan, at least, should’ve known better; he’d worked closely with Westerners for decades.

Not that anyone in high circles in Chinese politics wasn’t already convinced that the US was trying to bring China down, but moves like this will only solidify these sorts of views.

These protests surely weaken Xi’s hand regionally, as slowing growth and domestic troubles will call into question China as a model and economic partner. We’ve already seen Beijing reach out to the US to try to cool down tensions, an effort which culminated in the recent Xi-Biden summit. Even before the protest, I didn’t think any serious US-China cooperation was in the offing. That prospect has gotten even slimmer, though given the economic and social troubles at home I’d be surprised if Xi used this as a moment to escalate abroad. I’m not entirely sure whether the sort of deal the Chinese side proposed in the track II dialogue last week has gotten more or less attractive thanks to the protests.

As the impact of edge cases where the protests intensify, a violent crackdown would push some wavering countries in the EU like Germany to more aggressively break ties with the PRC. There’s also a very outside chance that things get bad enough at home that Xi decides a Wag The Dog-style escalation in Taiwan is necessary to rally support.

I’ll leave you all tonight with a voice from the Beijing protest.

Cogent analysis, none of which I disagree with. Might quibble about the probabilities you assign to hardening DZC and rapidly abandoning it, but not a serious objection.

Would be keen to see your thoughts on the longer-term implications, though.

I’ve said for years that the Party has been quietly laying in place the means to enforce its rule purely by force if they ever were to lose the “performance-based legitimacy” that rapid economic growth and advances in the standard of living granted them. Once Xinjiang really tipped over the edge and the central authorities felt compelled to back local officials’ descent into insanity to save face, they decided to use the province as a test case for the Toolkit for Technological Totalitarianism (TM) that they’d put together.

In 1980-89 and again after 1993 the CCP was mostly a fairly soft authoritarianism, to which the vast majority of the populace was just never subject. It’s becoming clear that going forward the Party (or at least Xi) is willing to change that if it’s necessary to maintaining its monopoly in power.

The main problem there, though, is that once they use it there’s no path back to the soft-ish authoritarianism of yesterday; they can never rule any other way than brute force and totalitarian control over every citizen, and the consequences for growth and standard of living are grave. Absent a literal coup and total course correction in the next few years, there is no longer a path to continued rapid advancement in standards of living. The Party-State is unable to make the necessary reforms to spur consumption and reduce reliance on investment and exports, let alone to allow private capital back off the hook and let it lay some golden eggs, and the stability, basic legalism, and faith required to facilitate business and personal endeavor all lay in tatters on the floor after the last three years.

The great unknown is whether technological means will make the CCP’s vision of totalitarian control possible, against the will of a majority of the citizenry making up the vast majority of economic activity.

The future, now, is basically down to the question of which is more powerful: the Party’s toolkit for social control on an unprecedented scale, or the expectations, aspirations, and willpower of the people.

Not a question to which I have a confident answer. Any thoughts?