China's True Tech Ambitions

"We don't ask ourselves how China competes or whether our investments in R&D are just going to fuel their rise"

The past two ChinaTalk podcasts were a ton of fun. Most recently, yesterday I put out a show with Nate Duncan of the Dunk’d On Podcast on China and the NBA. But last week’s with Emily De La Bruyere deserved the full transcript treatment. Her paper on China’s approach to scientific research is the best piece of China policy analysis I’ve read in 2020, deeply sourced in policy documents, and coming to powerful conclusions about the nature of the CCP’s tech ambitions.

Our discussion touches on why the CCP prioritizes applied over basic scientific research, the most important tech standards fight you’ve never heard of, the sad state of the US intelligence community’s open-source research, and why rare earths have led to these cows in Inner Mongolia having to graze on a moonscape. Do read the transcript below or have a listen.

Why China Spends on Applied But Not Basic Research

Jordan: China and the U.S. both see science and technology as an extraordinarily important strategic component to today’s contest, but you write they disagree over what it really takes to gain the upper hand in this situation. The discourse in the U.S. revolves around pioneering basic research, but by contrast, China prioritizes applications. Beijing’s strategic discourse and resource allocations focus on deploying rather than developing cutting-edge capabilities.

Emily: This research is the basis of really everything we’re doing now. Nate [Picarsic], my colleague, and I had these massive databases of Chinese science and technology resource allocations (i.e., funding) and prizes given out for advances in science and technology. Throughout all of these, we saw a tremendous imbalance between on applications as opposed to basic research––something that was entirely at odds with what would be the equivalent in the U.S. system. This didn’t make sense to us, and it particularly didn’t make sense in light of what we talk about in the U.S. as this Chinese push for indigenous innovation, for catching up, and for basic science and technology. If they really wanted that, why was that not where the money was going?

We found a discourse about how the current international system changes the meaning of competition in science and technology and how you can win that competition. There are two key parts: The first is that we’re in this globalized environment where information is largely open and flows across borders, and because of that the advances in science and technology are easier than they have ever been for a country to claim or access internationally. That lowers both the cost and the time necessary to get what’s at the cutting edge. And the corollary here is that it is very expensive to invest in basic R&D, and is very risky because you don’t know what’s going to work. Whereas if you obtain something that’s already developed or really close to reaching maturity, it’s cheaper and low risk, but that there’s a lag. In a typical science and technology contest, that doesn’t let you win the race. It lets you get to the end more cheaply, but someone else is going to beat you.

Which is what distinguishes today’s context, is what matters in terms of the end goal. The argument is that what matters today is the applications of science and technology––the sort of networks you build with it.

For example, your ability to deploy telecommunications … it’s not that you got the patent; it’s that you’ve got its application internationally. To do that, what matters is capturing scale and being able to build and deploy. If that’s what you’re going for, it’s okay to have a slight lag in when you get the patent and when you get the really cutting edge, as long as you can apply it to scale to the most people efficiently. The Chinese orientation appears to be focusing on that rather than on basic R&D, which creates this tremendous asymmetry vis-à-vis the U.S. and really vis-à-vis the entire global system because there’s just a different competition underway. And that absolutely changes how the U.S. can or should respond to the extent that this is a scientific and technological contest because it’s not a matter of just pouring resources into basic research: it’s about competing for applications.\

Jordan: This idea of “why buy when you can rent” makes a lot of sense. Is Chuck Schumer pouring a hundred billion dollars down the drain, trying to boost National Science Foundation funding to do this sort of basic research, only for it to show up in Chinese companies two to three years later?

Emily: Yes, that’s what we’ve seen, and that’s the crazy thing: the U.S. says there is this contest and we need to invest in science and technology because we’re competing against China. But what they don’t ask is “how does China compete” or “what are our resources actually going to fuel, now that we’re benchmarking against a competitor” or “are they in fact just going to fuel our competitor?”

Jordan: I still want the future to come faster, and I think the only nice thing to come out of the U.S.-China tech war is increasing funding for this sort of stuff, but I take your premise at a certain level.

Emily: I still write on a typewriter, so that might be the problem here.

America’s Garbage Infrastructure

Jordan: Fair enough. Why don’t you sketch out what investing in applications would look like in the U.S. context? Because I think the sort of layman’s take is that this is picking winners and losers, and turning Verizon into Huawei somehow, and just doing sorts of things that aren’t necessarily all that comfortable or compatible with the way that the U.S. has done industrial policy over the past fifty years.

Emily: Yeah, that’s a really good point. There are two ways to frame this. The first is that already the U.S. R & D money goes to various tiers on the readiness scale, so part of it is just shifting it to more mature research.

I care about the most boring things in the world. The list of things I’m passionate about other than like typewriters is probably infrastructure and logistics. And at the core of this is that the prime manifestation of what it means to invest in applications is to invest in infrastructure. For example, in telecommunications infrastructure, we’re so busy talking about who’s going to capture the cutting-edge research on 5G that we’re not talking about our ability to actually develop 5G systems, which require a mass infrastructure of base stations.

Do we even have 4G across the U.S. right now? No. How is that possibly going to happen? How do we actually compete in not only 5G but in the entire ecosystem of technologies built on 5G, if we can’t lay out a scaled telecommunications infrastructure across the country? And then the same story holds for self-driving vehicles or electric vehicles. What about the charging stations? What about the actual abilities to have the networks on which all of these things can operate? And interestingly there’s a big push in Chinese discourse right now that dates back to 2018, but has been accelerated with their COVID recovery investment, for “new infrastructures.” These refer to the infrastructure of, if you will, an internet-of-things ecosystem. So it’s data centers, it’s telecommunications base stations, it’s UHV (ultra-high-voltage electricity transmission), it’s electric-vehicle charging stations. These the really boring things, but they’re what the physical foundation is. What does it mean to have the cutting edge of cloud-storage technologies if you don’t have the data centers in which you store them?

Jordan: It’s interesting this dynamic because I’ve come across and translated a handful of commentaries from anonymous senior Chinese scientists who are not particularly happy with this. There’s clearly a constituency out there that wants to compete and have, say, a really cool new Large Hadron Collider, or just do the real basic research that ends up winning Nobel prizes. But at the same time, there’s an understanding in the government that if you want to compete on a global scale in the way that Xi Jinping defines it, then investing in that sort of scientific-research ecosystem is not necessarily going to get you there.

Emily: Exactly––it’s like you take a fine-art painter and you say, actually, it’s going to be a lot more useful for you to paint a lot of houses. And that’s maybe not what they want to be doing when they want to be doing the Sistine chapel.

Why the CCP Strives for One-Sided Dependence

Jordan: What’s this idea of one-sided dependence?

Emily: Fundamentally one-sided dependence in the U.S.-China context is the idea that we in the U.S. might enter into a system in which we depend on China, but China does not depend on us. Or more realistically, we are relatively dependent on China and China is relatively independent of us, because it’s really just all about the relative relationship. And that’s encoded as an ambition in Chinese strategic theory.

Jordan: And this is decades in the making.

Emily: Exactly. There’s this strategic theory called “Two Markets, Two Resources” that dates back to the 1980s. It’s actually the theory that undergirds the whole “Go Out” national strategy. There are all sorts of political reasons that it’s not necessarily cited as such, but it is.

The idea of Two Markets, Two Resources is that there’s a distinction between the domestic market and the international one, and between domestic resources and foreign resources. And you want to protect and insulate your own resources and markets while penetrating and being able to take advantage of––and also secure influence in––foreign resources and foreign markets.

This is particularly tangible and obvious in the case of mineral resources––the sort of inputs of relatively limited supply that are really necessary for emerging industries. China has a very careful system built to protect its own mineral-resource reserves, to control their export, and to determine how and by whom they are mined and processed. At the same time, they are trying to invest internationally in consolidated sources of these resources of limited supply, for example, cobalt in the DRC. Those investments are not just designed to meet some domestic need or for immediate profit. What they’re designed to do is grant China relative influence over the supply––and therefore the market and prices––of these goods. It’s to create a world where the market system for cobalt, and therefore for the industry that is built on top of cobalt, depends on China while China maintains its own relative independence.

Jordan: Sure, but there are points which this model hasn’t been built out currently (like for semiconductors), which is why you see Xi Jinping spending a trillion and a half to close those loops and change the relative balance.

Emily: To a degree, but actually the semiconductor example is a great one. Semiconductors have this whole industry chain, from upstream to downstream, in terms of the sophistication of the technology necessary. China does have key nodes, particularly in the upstream of that industry chain, so the semiconductor industry relies on China at the lowest levels, which are of course what everything’s built on.

China relies on the rest of the world for the downstream––the highest, the most advanced levels. But at the very least, it’s a balanced relationship. In some Chinese texts, you actually see the argument that it is more strategically valuable to have that low level because everything is built on it, whereas it’s only the high-end applications that are derived from the top. So you have this early choke node, if you will.

Branding a Strategic Plan

Jordan: How about U.S. responses to Chinese plans? One of my half-baked theories is that had Made in China 2025 not sounded so catchy in English, it wouldn’t have gotten nearly as much play or engender nearly as much of a response.

Emily: Or if it had been The 863 Program, cause no one knows what the 863 program is, and it’s just as explicit.

Jordan: Well “Torch” sounds scary, but how about the “Two-Machines Special Project”? What are you going to do about a Two-Machines Special Project? There are no puns. There’s no op-ed headline with that phrase in it.

Emily: Trust me, I’ve tried to pitch that op-ed, and no one wanted it.

Jordan: There’s an interesting, broader thing going on: The way the Chinese system works, you have to publish a plan if you want such an enormous bureaucracy that runs a billion and a half people to try to execute it. If you want to do these things, you have to be very explicit in order to get the local- and provincial-level governments to do what you want them to do. You can’t secretly try to create your own semiconductor supply chain or what have you.

But at the same time, I feel like there was a middle ground that Xi could have done to slow-roll this, maybe to talk less aggressively, because just doing the World Economic Forum speech isn’t enough. Not many people speak Chinese, but enough speak Chinese to be able to process the kind of narrative that you and others have been writing about for years now.

Emily: If you look at the names of these plans, they mirror the growing assertiveness of China on the world stage. The decision to say, “we’re going to put out a plan called Made in China 2025” is a decision to say, “we’re going to claim this posture internationally and we’re going to be apologetic about it.” This was a gamble about the relatively closed eyes in the U.S. that maybe it was a little overconfident, but apparently not so much because China just pretended to stop using that plan’s name for a little while, and everyone bought it and thought, “We succeeded! They ended Made in China 2025,” when it wasn’t ended at all, there was just a little hush in the English language. These ambitions have been so explicit in Chinese and no one’s caught on, so there’s every reason for them to think they can get away with Made in China 2025.

Jordan: I think there are broader forces at work, which have led to ZTE, Huawei, and now the U.S. trying to spend billions of dollars to address these questions. The naming and the other ambitions from back in 2015 clearly attempted to get people’s attention focused on this, and it does strike me as a bit of a misplay on their part. On the one hand, it’s something that certainly energizes your bummed out science researcher who doesn’t get to paint the Sistine chapel and is stuck painting cars. But on the other, there clearly was a real response in the West over the past five years, which has now contributed to the situation that we’re in today.

Emily: Absolutely. You can get a rise out of someone if you say a company is a part of Made in China 2025 that you can’t if you say they’re part of the Strategic Emerging Industries initiative, even if those really occupy such a similar place and represent such a similar set of ambitions.

China Standards 2035 + Logistics!

Jordan: Let’s get to China Standards 2035. What are standards? Why do they matter? And what is China’s plan for them?

Emily: Standards are the rules of the world. In this case, technical standards are the rules that govern international technology, so that really set the rules of the world. China has been focused in an unprecedented way on setting international standards since the late 1900s, but as a national strategy since 2001, shortly after they entered the World Trade Organization.

The first thing to note here is that this is really very unique to China. Historically speaking, standard-setting and standard-setting organizations have been cooperative processes and fora. This is something that companies did together not to compete, but so to ensure interoperability among their various niches. But from a strategic perspective, China clearly saw that in setting standards you get tremendous strategic value––there are automatic economic returns. Those are huge, but there’s the added benefit of being able to write the rules, which means that you can influence how things work.

Jordan: You write that “a logistics information system hardly sounds like the stuff of great power politics. It certainly does not sound like a bid to redefine global affairs. In fact, it sounds unfathomably boring, but it’s important.”

What is LOGINK and how does it apply to the themes you just laid out, of going from a real to a virtual economy and this idea of leveraging standards and turning them into platforms?

Emily: I love this one particular logistics information system as a relatively tangible example of everything that I talk about. The goal is for this to be a super-app of sorts, a one-window platform for information on international logistics. It’s supposed to be multidimensional in terms of different infrastructure systems, so to cover land and air and sea and freight and post. Right now in its international manifestations, it’s really mostly in the maritime domain, but there are dozens of international ports that connect to it. LOGINK (National Logistics Information Platform) has partnerships with multinational companies, as well as with international standard=setting organizations and industry organizations, in particular, the IPCSA (International Port Community System Association), which is pretty much the industry association for port operators.

The idea of LOGINK is that it connects to companies and infrastructures like ports, and it aggregates their information on the movement of goods, the packing and unloading of goods, customs systems, ships’ backgrounds and personnel, etc. Then it creates a Facebook of sorts––this platform where you can find that information. You can also use this foundational information layer to build applications on top of it, or checking logistics software at the port. This is tremendously useful because right now this information is siloed––there is no aggregated portal for all of these different streams of largely incompatible information. The other thing about LOGINK is that it’s also being presented as a technical standard for information logistics, and right now the standards aren’t compatible with each other, so it fills this incredible market gap. But the thing is that LOGINK gets controlled by China’s ministry of transport, so you have these immense streams of information that are both commercially and militarily valuable, and that are going to a Chinese government entity.

The other thing that LOGINK could do is shape the information environment, because companies, ports, and users are going on here to see how goods are moving, to find a port logistics software to process their customs paperwork, etc. What happens if the information on LOGINK is in such a way that it benefits China or Chinese players––if Chinese softwares are the ones that are suggested the way Amazon suggests a product, and therefore they’re the ones that are used, regardless of any quality or security concerns? What happens if the customs processes on LOGINK, which create this great super convenient integrated system, make it easier for certain players to transfer elicit or controlled substances? And what happens when there’s a confrontation and China wants to cut off supplies of say rare earths to another country, and that country’s ports, or the port shipping the rare earths, use logging for their information?

Jordan: How many places have you gotten this op-ed rejected from?

Emily: I cannot count, actually. Anybody listening, we have a report on LOGINK that we’re hoping to drop in the next week! So we’re actively in the process of looking to place two op-eds on this subject right now.

Jordan: We touched a little bit about this: What is different about the world today versus 30 years ago? And what’s special about China that gives this whole prioritizing applications, standards, and companies a chance of working, while the playbook that a lot of other countries that have made it from middle-income to high-income status doesn’t really line up.

Emily: For the first half of that question, what’s different is information technology, and what information technology brings about, i.e., globalization. What’s different about China is its size and centralization, and also the ability to take that information technology and to use it strategically, whether in terms of maintaining an authoritarian system (which, unlike authoritarian systems of the past, could potentially not be hugely expensive but instead end up making money) or in terms of projecting its power internationally.

Both of those are fundamentally about similar things. Take, for another example particular to China, the Military-Civil Fusion (MCF) strategy––the idea of combining all these different strains, which for whatever reason in international relations have come to be seen as siloed or different, into a vision of “comprehensive national power.”

Then based on that idea looking around and saying, “how can we project power through information-technology systems or other unusual forms of global presence that simultaneously deliver commercial value and promise military utility.” At home, this could be the idea of a surveillance system that, because it collects data on individuals, can also be translated to “data as new oil.” Or there’s the idea that if you have an international port logistics network, that can be translated to influence across the world, in addition to the commercial utility you get from collecting information.

Mil-Civ Fusion

Jordan: Let’s talk a little bit more about MCF, which is something that sounds very scary and something that I’ve seen a lot of Chinese writers be very proud of. I’m a bit of a skeptic about this, not from any informed opinion, but just from thinking about how bureaucratic and slow-moving the Department of Defense is: imagining that in a Chinese context, the people who are within government working on these things have an even worse pay differential relative to the private sector; the fact that the ecosystem of state-owned enterprises is pretty far from the cutting edge; and finally the private sector that really doesn’t want to do any of this, and has to be dragged kicking and screaming into cooperating on some of these projects.

So my question is, how does this actually play out in context? Is this something that you can figure out from doing this sort of open-source research that you’re doing? What are the kind of bumps and hiccups that you see Chinese writers talking about when looking at their views of how MCF is actually going?

Emily: There are two levels of analysis to this question, and the first one, which I find most compelling, is the strategic orientation behind MCF. The idea that you’re fusing commercial and military resources and actors, and positioning for the sake of a unified goal, because that’s a different way of thinking about these things than what you see elsewhere. Until recently, if not still in the U.S., we have this idea that in the commercial world you cooperate, and in the military world you compete; you can be really good commercial friends with another country even if you have this military snafu going on.

But if you accept the fundamental strategic premise of MCF, is that possible? Or is this player with whom you’re holding hands on one side and fighting on the other actually fighting with you on both? That is the first thing to wrap our heads around. And then there are the more granular tactical details of how MCF works and whether technology is actually being shared perfectly between these different entities.

Everything you said is accurate: technology sharing and data sharing are not obvious things that happen easily. There are plenty of hiccups, and bureaucracy is bureaucracy. To a nontrivial degree, you can figure most of this out with open-source research. Shared laboratories are a good example of this. You can look through the Chinese R&D and S&T laboratory ecosystems and say, “where do you have a laboratory that is jointly engaged by a commercial champion and a military entity?” Then ask “what research is being done there?” This can be mapped in a bottom-up way, and you see that these do exist in a real way. If you can pair the mapping-out with what you find on information sharing, you see the degree to which regulations are actually being carried out.

MCF is real, especially in areas that are prioritized. It’s not happening across the board, and it requires building an infrastructure that isn’t in place entirely.

Jordan: What is prioritized and easy?

Emily: Easy are things that are very specific and have very direct military utility, for example, explosives. There’s this case of a Chinese mining company that just did regular mining stuff, and then they came out of nowhere with this crazy missile. Which is ... a little bit of a surprise. This is one example where you can say “here’s one specific company we’re going to turn that into one specific thing.” That’s what easy is.

I’d say that another thing that is definitely prioritized is information; for example, the satellite system BeiDou. The idea of using a commercial entity to collect global information and sense, and then dock that into the military system. This whole idea of information warfare and competition for information is the priority for Chinese military strategy, and BeiDou is framed as the commercial champion of MCF. So I’d definitely put that at the top of the priority list.

Rare Earths as a Weapon

Jordan: Talk some more about rare earths. I won’t make you explain what rare earths are ... Rare earths: China has a lot of them; the world needs them. You’re hearing more and more talk on Capitol Hill about doing something about this, but in the meantime, or at least over the next few years, this is going to be a vulnerability Do you have a sense of if and when this card is going to be played?

Emily: Well first of all, for some important context, it has been played vis-à-vis Japan in 2010, over the Senkakus. How is that not more present in the popular consciousness? That was an insane move.

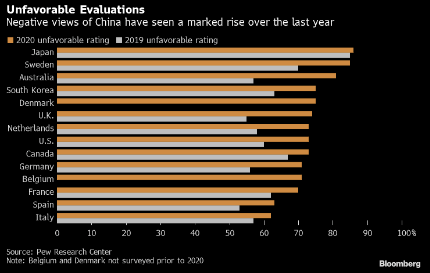

Jordan: Yes, and it’s interesting because the Russia-Ukraine oil thing really made people wake up, whereas this moment hasn’t at all. I think the answer is that people think, “oh they’re just these stupid islands, and the Japanese and the Chinese always hate each other.” I saw a great graph today on Twitter. It was someone talking about national populations and their views of China, and every country in the world got 15% angrier at China in the last year … and Japan didn’t. Because they were already at 93% and it was literally exactly the same, which I thought was pretty perfect.

Also consider in 2010, China’s growing at 10%. They’re also the economy that’s saving the world after the Great Recession, and there’s just a lot of incentive to not think too hard about these sorts of questions, way back when you have Hu Jintao in power.

Emily: And you’re just starting to get the South China Sea thing, but people are confused at what it is in the South China Sea and why they’re supposed to care.

Jordan: So yes, it has been played, but playing it in the U.S. context with Apple phones or whatever would be at a very different, global scale. You’ve cited a handful of Chinese scholars, and I think even the Chinese government, in saying that this is something that may come to bear when it comes to U.S.-China trade negotiations and the trade war back in 2019. Talk about how the Chinese government sees this asset, which, as you write, has been consciously developing as a strategic resource since 1961.

Emily: There’s a great line that China has been focused on rare earths since the very founding the People’s Republic of China. China has natural rare-earth endowments that give it a fundamental advantage, but China has very intentionally curated an advantage in the processing and the production of rare earths. as well as investments in international rare]earth supplies.

This goes back to that Two Markets, Two Resources conversation––the ability not just to have one’s own resources, but to influence the world. There are indeed Chinese sources during trade-war frictions that say “we would consider using this as a course of leverage in the case of international conflict.”

Will this ever come to pass? Unclear, because the ideal situation from a Chinese perspective would be that it remains a lever of influence that shifts behavior, but that they never have to pull, because then they can shape things without entering into an actual conflict. It’s also worth noting that there is a new growing U.S. recognition of the rare-earths imbalance, but in a way that risks not accounting for the nature of China’s rare-earths positioning for the degree to which they invest in international sources, including in U.S. sources.

It’s not enough to just say, “that facility or that reserve is not in China,” because it might be equally influenced by China. The other thing is the whole industry chain, because rare earths are not just a question of the reserves: it’s a question of the processing, and the technology and equipment that’s necessary for that. You get stories of U.S. investment in a source in the U.S. that’s supposed to be an alternative to China, but they’re importing all of their equipment from China. How much does that actually break dependence? Not so much.

Saying “we promise we’re squaring the circle” goes back to the question of how this could be used. It’s important to keep in mind that any rare earths leverage, like any leverage in the Chinese industry chain, could be used more subtly than just saying “we’re breaking off exports.” It could be, “this company is going to have a harder time getting the equipment they need.” It could be just making things a little more difficult, and that allows all the subtlety without the conflict that might bring recognition and a wake-up call.

Jordan: I feel really bad for Inner Mongolia, just in terms of the poor Mongolians, they just want to herd their freaking cattle and sheep! All of a sudden these giant, Han-owned companies show up and are now drilling and ruining the grassland. And I’m sure they’re not getting any benefit from all the cobalt or whatever is being pulled out of there, and the same thing goes with minorities in Sichuan province.

Emily: They’re polluting so much! China makes all these claims to be supporting whatever environmental thing the world is now supporting, but then say “oh that doesn’t apply to inner Mongolia or to Zhejiang because if that just doesn’t apply there––oh wait––we can have some real cheap rare-earths processing.”

Jordan: Let’s square the circle: How does LOGINK connect to rare earths?

Emily: Here we go! There is a port in Malaysia that docks into LOGINK, and that port just happens to be a stone’s throw from this rare-earths facility, which is run by an Australian company in which the U.S. is currently investing as an alternative to Chinese sources of supply. It seems great that we’re looking for alternative sources of supply, but this actually means that China threatens having better information on the rare earths that are going from this alternative source of supply to the U.S. than does the U.S. itself. Additionally, the port on which that facility depends risks depending on China. This is a classic example of us not understanding the extent or the nature of China’s positioning, and then us investing in things that risk being counterproductive.

How America Could Overreact

Jordan: Emily, you’ve, in the past hour, laid out the maximalist version of what threat Chinese industrial policy has for the West. If this conception of Chinese intentions and ambitions is being internalized more and more in the West, I have zero faith in the U.S. in particular, but the West in general, in coming up with a smart way to do this––coming up with a solution that does not entail just cutting off China whole-hog from the global economy, having no Chinese nationals ever get a visa in the U.S. again, and a whole host of other side-effects of decoupling.

These may address some of the concerns you’re laying out, but they will also have real deleterious side effects, which go beyond industrial policy and will end up completely defining how the West relates to China for the next … however long we have a Xi Jinping–type leader in power. To what extent do you share this concern, and how can you be hopeful that policymakers will not end up going down this sort of road?

Emily: I absolutely share that concern, especially because the blunt, dumb version of this ends up being a bad thing for the U.S. And that, as well as not reacting at all, could make us lose the contest currently underway. One of my other fears, and probably the thing that I’m most worried about, is that the U.S. tries to do this alone––tries to take radical actions on its own, or acts so bluntly it pushes other countries away, i.e. Europe, away.

The U.S. can’t compete on its own. If that happens, it pushes Europe and the rest of the world toward China. The things that the U.S. can actually use as leverage right now, like advanced technology, China already gets from Europe. America, can’t rival the scale, and the battle’s over. If the U.S. is going to win it needs to be working with its allies and partners. Acting bluntly and assuming we can just decouple, which goes against everything that is true of the international system right now, just pushes allies farther away.

What we do need to do is strategically have a taxonomy of what is important and realistic in terms of protection––in terms of investing in alternatives. We can’t just bluntly try to decouple without investing in the alternatives and do what we’re doing with Huawei right now, where we try to rip them out and say “Huawei is bad” but don’t present a positive alternative. That’s the perfect way to lose. What you need is a strategic taxonomy that takes into account what you can do and what you can’t do, what’s important and what isn’t important, defense and offense together, positive and negative, however you want to put it.

There’s the other issue that the U.S. isn’t good at strategy. The U.S. has never been good at strategy, and the U.S. is particularly bad at strategy in a system like our current one where there isn’t an entity in charge. Instead, there are supposed to be a bunch of different players working together to somehow formulate a logic that’s going to comprehensively guide us somewhere. That is not going to happen. They all have conflicting political intentions, bureaucratic intentions, different structures, different mandates, etc. Until we’re actively working with allies and partners, and until we have a body that is small and flexible and superordinate and dedicated to this, we kind of risk having a snowball’s chance.

How US Open Source Intel is Failing

Jordan: I have another question that’s not related: The House Intelligence Committee came out with a report two days ago about the state of the Intelligence Communities (ICs), particularly open-source Chinese analysis. A lot of it was redacted, but basically it said, “we’re doing a really bad job and we need to scale this up.” As a young person who does this full time and who’s interacted with that world, do you have a sense of where the IC is with this sort of thing? What did you think about this report in the issue more generally?

Emily: I absolutely agree. What I do should not be unique, and should definitely not exist only outside of the government. The IC has so much information, and there are very smart people looking at this information, but I worry that it’s the wrong stuff. The U.S. system should know about LOGINK, and it should have known about standards ambitions, but we still have a strategic framework that dictates what information to collect and what information matters that is outdated the current competition.

Jordan: What is it?

Emily: It that focuses, for example, on which naval ships China is developing and where they’re moving. I don’t care about that if China has the fundamental architecture that watches how ships move. You don’t go anywhere until you are formulating––in an iterative, living, breathing way––what it collects based on Chinese strategic thinking, or the very least going through a renovation in terms of what it looks at that will account, for example, for MCF, or for commercial movements, or for movements of capital that overlap with the military domain. Until you have that, you risk having a lot of information and asking the wrong questions. If you’re asking the wrong questions, you don’t get anywhere.

Jordan: You’re also training people on things that aren’t as important as these sorts of questions, because you can spend your entire life looking at where cruisers are going and understand the captain of this ship takes naps from 2:00 to 7:00 pm, but this sort of work is less concrete. I assume that is a difficulty for a bureaucracy trying to wrap its head around these nation-state-level things, which it hasn’t had to do since 1989, and then having to build back those sorts of muscles. This sort of capability is something that more and more people seem to be aware of as an issue. Hopefully, it’s something that’ll change in the near future.

Emily: The other problem is simply the problem of classified information. There’s so much out there in the open-source, but if you have a clearance all you’re looking at is the classified stuff. You think that’s all that matters, but you risk ignoring very compelling stuff that’s in the open-source, or you have an overflow of information.

Jordan: On top of that, there’s the issue of clearances. This sort of thing, understanding Chinese MCF, for example, you can probably figure out while not having spent five or ten years in China. As a U.S. national living in Beijing for five or ten years, you’re not going to work in anything close enough to this to really gain all that much expertise. If you’re trying to understand trends on social media, and it’s February 2020, and all of a sudden people are screaming about Li Wenliang and trying to figure out what exactly is happening in coronavirus …

The analogy I like is all of a sudden you’re a Chinese person who speaks pretty good English and has never spent time on Twitter, and all of a sudden is told, “figure out what Twitter’s talking about today.” You need someone who’s lived and breathed this stuff and has spent all their spare time engaging with Chinese pop culture, Chinese celebrities, Chinese bloggers, and what have you. That sort of person has the background that makes it nearly impossible for them to get a clearance, to do this sort of work in the first place.

(Will send Tweets of the Week over the weekend, this email’s already too long!)

Thank you, that was a good read