Lily is representing ChinaTalk at ICLR this week! Send us a message if you’re going and would like to meet up.

Liberation Day was just the beginning — Trump declared that he will be, “Taking a look at semiconductors and the whole electronic supply chain.” What could happen next and what would be the smart way to go about this?

Welcome back to another CSIS Chip Chat. Joining us today is CSIS’ Bill Reinsch, a longtime Washington vet who co-hosts The Trade Guys podcast, as well as Jay Goldberg of the Digits to Dollars blog and The Circuit, an excellent semiconductor news podcast.

We discuss…

The conflicting goals of Trump’s tariff strategy,

What chip designers stand to lose in a worst-case scenario,

Why tariffs could undermine the enforcement of SME controls,

How Chinese chip companies benefit from American tariffs,

Loopholes in the H20 ban, and how the administration could close them.

Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app.

Tariff Anxiety and Trump’s Objectives

Jordan Schneider: We’re recording this interview on Friday, April 18th. What are we looking at with the tariff situation right now?

Bill Reinsch: Tariffs are on the way. That includes tariffs not just on semiconductors, but on a wide range of downstream products. That could be very disruptive to the economy, depending on the specifics. If it has a chip in it, it may be vulnerable. Thanks to the Internet of Things, that’s a lot of stuff — it’s toasters and refrigerators as well as laptops and phones.

The mystery is what he’s trying to accomplish because he’s given out conflicting goals.

One goal is revenge — getting even with the countries that have taken us to the cleaners for the last 50 years.

Another goal is to use tariffs as a negotiating tool to get other countries to remove trade barriers. It’s artfully designed such that we don’t have to do anything. All we have to do is wait for them to make concessions, and then our concession will be not to impose the tariffs that he’s announced. If that works, that’s a good deal.

The third goal, which is inconsistent with the first two, is revenue. They need money to pay for tax cuts. Our current estimate of tariff revenue is $330 billion a year, which is not peanuts. But that’s only true if the tariffs stick. If he negotiates them away, then the revenue goes away.

The fourth goal, which is the most interesting one, is to reshore manufacturing. If you make it here, there’s no tariff. But there’s a time gap — tariffs go into effect now. If you’re building a factory, it takes lots of money and lots of years to put the pieces together. You have to find workers to fill the jobs.

Which is the real goal? It changes from time to time. With chips, it’s particularly hard to tell. It’s not really a revenge issue because most of this stuff is covered by the Information Technology Agreement, so it’s zero tariffs already. It’s probably trying to force manufacturing here, but in the process, it’s going to be one of the largest revenue transfers from the poor to the rich in history because the poor pay the tariffs disproportionately. The tax cuts also go to the rich disproportionately. This will make economic inequality in the United States a lot worse than it already is.

Jordan Schneider: If you’re a major chip designer, what’s going through your mind at the moment?

Jay Goldberg: If you’re a major chip designer, you have two concerns. One is losing access to the China market, because if China’s going to use counter-tariffs, suddenly your products are much more expensive. The other concern is tariffs on Taiwan. I know there are all kinds of side agreements and other things going on here where some chips are coming in at zero tariff, but is that going to continue? It sounds like there are threats to impose more tariffs on Taiwan for various reasons.

Not all chips are covered. GPUs aren’t covered under the rules — GPUs actually get tariffed. Semianalysis put out a good piece last week showing that there’s a loophole. If you import your tariffs through Mexico as part of a system, then you don’t get that tariff. But if you import the GPUs directly to the US, they’re tariffed differently than CPUs, which hurts my brain and just seems counterproductive. Do you want to do assembly in the US? Well, you’ve just made that more expensive than doing assembly in Mexico. Do you want to win the AI war, whatever that is? You’ve just made that whole process more cumbersome and more expensive.

I’m confused — that’s where I end up on it. But to answer your question, if I’m running Qualcomm or Nvidia or Broadcom, I’m worried that suddenly my products are going to be more expensive somewhere along the line and that I’m going to lose access to 10-20% of my revenue that goes through China.

Jordan Schneider: All right, let’s discuss manufacturers and manufacturing.

Jay Goldberg: Regarding Bill’s question about our goals — do we want to bring advanced manufacturing and semiconductor manufacturing back to the US? If that’s the objective, we’ve already achieved it. We have TSMC building advanced chips in Arizona, so the supply chain is secured. That plant is very dependent on Taiwan’s mothership for R&D.

If you want an American company to have advanced manufacturing of semiconductors in the US, then the solution is simple — give Intel $50 billion. Problem solved. Intel can manufacture chips — it’s not a technical problem anymore, but an economic one. They just need to overcome certain cost curves to manufacture here.

If this were purely a national security concern and we wanted a fully domestic supply chain in case of war, then investing heavily in Intel would accomplish that. However, this approach creates other issues since we generally don’t favor subsidies. The ultimate goal remains confusing to me.

Bill Reinsch: There’s an important distinction you’re making. Biden was more of a carrot guy while Trump is a stick guy. Biden’s approach was to incentivize companies to do what we want. That’s essentially what the CHIPS Act was about, and likely much of what the IRA addressed — tax credits, subsidies, and incentives.

Trump takes the opposite approach. He threatens and pressures companies into compliance. It’s much cheaper for the federal government but not necessarily cheaper for the companies, as you’ve pointed out.

Jay Goldberg: In a modest attempt at bipartisanship, I’ll acknowledge that the Biden administration wasn’t particularly clear about its semiconductor objectives either. Their semiconductor initiatives contained many conflicting goals.

Bill Reinsch: I wouldn’t disagree with you on that.

Jay Goldberg: The current process is quite confused. Our objectives aren’t clear, and most paths forward involve everything becoming more expensive for average consumers. Then we face the question of China’s response, as they have some serious counter-tariffs that are detrimental to all these companies.

Bill Reinsch: The tariff levels are so high that they’ve essentially prohibited most trade between the two countries if they remain in place. My footnote to your comment is that Trump wants a deal and believes he can negotiate one with his “good friend” Xi Jinping.

This causes some concern within the administration because he appointed several people who are “decouplers” — they don’t want anything to do with China. But Trump maintains that he can make a deal. When he says that, as he has a number of times, I think back to 2018 and 2019. We’ve seen this movie before — he negotiated and made a deal, but in my view, he got played.

He entered with a whole bunch of demands and ultimately settled for promises to purchase American goods, which China never fulfilled. When questioned at the press conference about all his initial demands — eliminating subsidies, stopping IP theft, and other legitimate concerns — he responded that those would be addressed in “phase two,” which never materialized. I believe we’ll see a replay of this scenario.

Jay Goldberg: Then they didn’t follow through.

Bill Reinsch: Right now, it resembles a sumo match. You have two enormous opponents in the ring doing a lot of foot-stomping, glaring, and frowning at each other while throwing rice around. Eventually, there will be contact, and they’ll get to the negotiating table.

The only challenge is disguising who made the first call, because neither wants to be seen as the initiator — they both want to appear as the gracious party. An announcement will simply state that the two leaders have spoken and a meeting is scheduled, without mentioning who reached out first.

After the meeting, I expect similar results to before. Perhaps not 145% tariffs on Chinese goods or 125% on American goods, but some smaller figures. Currently, I don’t see any scenario where these numbers drop below 10%, which represents a significant increase for the US, whose average tariff level for decades has been around 2-2.5%.

Jordan Schneider: I’m somewhat disappointed. There’s a prediction market on whether Trump will impose 200% tariffs on China before June, and we’re now down to 19% probability. It spiked to 60% at one point. If we’re going this high, why not go for 1,000%? How about 949%? Let’s really make a statement.

Can China Capitalize?

Jordan Schneider: Let’s take a more positive approach. Bill and Jay, how would you use tariffs to influence the semiconductor industry?

Jay Goldberg: A few weeks ago, the Chinese establishment appeared very nervous. Obviously, I have no insight into what Xi Jinping or senior party members are thinking, but from the semiconductor industry commentary I was reading, there was genuine fear and trepidation.

That shifted the moment the tariffs were extended to the rest of the world. Liberation Day was a positive development from the Chinese perspective. If Trump had maintained his focus solely on China, there was a moment when he could have genuinely affected the balance of trade.

Instead, he imposed tariffs on everyone else, alienating our allies. Then he reversed several tariffs, which undermined our negotiating position. There was a brief window when he actually had a chance at achieving his objectives.

Bill Reinsch: China should return to being worried because negotiations with other countries will likely unfold in a specific way. These nations are lining up to visit the US, and during these discussions, one of our major requests will be for them to match our approach toward China by imposing similar tariffs. While this isn’t specifically about semiconductors, it’s an important ask that will resonate with some countries.

Chinese overcapacity affects several sectors — steel, aluminum, solar panels, electric vehicles, and soon commercial aircraft. Other nations are beginning to recognize how this damages their domestic industries. The European Union’s concerns about EVs are shared by India, Turkey, South Africa, Brazil, Canada, and Indonesia, all of which are taking or considering tariff actions against China for various reasons. Indonesia’s focus is on textiles, which differs from the others.

Many countries have identified the problem and recognized that it’s detrimental to their interests. What’s missing is a coordinated approach. Unilateral action is like squeezing a balloon — the pressure just shifts elsewhere. The primary victim of our actions against China will be the European Union, as products no longer sold to us will be redirected there, which concerns them greatly.

If a collective strategy works, China will face a united front rather than just bilateral conflicts with individual countries, creating a much larger problem for them.

Jay Goldberg: That’s absolutely true. My concern is that Europeans no longer trust the United States to lead such a coalition effectively.

Bill Reinsch: You’re exactly right. We’re alienating our friends more than our enemies. Russia and Iran were exempted from the tariffs. While we don’t trade much with them anyway, it was an odd symbolic gesture. Given how we’re treating our allies, why would they help us? It simply doesn’t make sense, as we’ve already noted.

Jay Goldberg: I recently saw a report about ASML, which produces critical EUV tools essential for advanced semiconductor manufacturing. During the Biden administration, they provided software security keys to the NSA and US government to prevent China from using their most advanced systems. My understanding is that after the new tariffs were implemented, the Dutch government reclaimed those keys, moving us in the opposite direction.

You’re right about the common interests among nations. All the countries you mentioned, plus others, have legitimate concerns about China’s export practices. Eventually, we might align our approaches, but collective action is essential. Otherwise, we’ll remain fragmented.

This sentiment was reflected in Chinese media — initially, they were worried and felt isolated. Then “Liberation Day” arrived, and their tone changed overnight. They became optimistic, with some explicitly stating that the US had overplayed its hand, transforming the situation from “the world against China” to “the world plus China against the US."

Bill Reinsch: That’s a fascinating perspective. I hadn’t considered it that way.

Jay Goldberg: I’m trying not to sound alarmist. You’re right that countries are preparing to negotiate and seek agreements. Hopefully, some of these discussions will develop into collective action against China rather than just a series of bilateral arrangements.

Bill Reinsch: My instinct suggests that Japan and Korea will be the most reluctant participants in such collective efforts, which is particularly relevant for the semiconductor sector.

Jordan Schneider: Yes, the secondary impact on semiconductor export control. We saw the H20 affected earlier this week, but that’s relatively straightforward. Manufacturing equipment requires cooperation from allied nations. While extraterritorial measures might allow for tighter restrictions than previously possible, I have mixed thoughts about this situation.

These countries will be more concerned about broader trade disruptions, making Tokyo Electron’s challenges seem minor compared to potential 20% tariffs on their entire economies. However, this approach creates an unfriendly atmosphere when making additional requests. If these nations are reconsidering their relationships with China, semiconductor restrictions are precisely what will frustrate them most.

Bill Reinsch: China has launched what appears to be its third charm offensive. The United States is essentially signaling to the world that we’re no longer a reliable partner, which has profound implications.

One particular concern, magnified by our implementation approach, is the lack of consistency in our policies. Tariffs are imposed, removed, increased, and decreased; exceptions are announced, then withdrawn, then postponed; deadlines shift, and deals emerge unexpectedly. From a foreign perspective, predicting our next move is impossible, and there’s little confidence that any agreement will endure.

Canada and Mexico provide prime examples. Trump negotiated the USMCA, which he declared the greatest trade agreement in history, yet five years later, he’s dismantling it. Under such circumstances, why would any nation trust our commitments?

Jordan Schneider: The Biden administration managed to bring the Netherlands, Japan, and South Korea on board to some extent, but their primary directive was maintaining good relationships with allies. This approach limited how aggressive they could be on semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) restrictions.

With Trump, we’re seeing different motivations at play. First, there’s less concern about allies’ reactions. Second, there’s a stronger desire to confront China. Third, there’s a simultaneous interest in making deals with China. These competing priorities could lead to various outcomes where allies become alienated.

As a result, companies like ASML might stop caring about finding ways to service DUV equipment or sell EUV technology to China. Alternatively, the administration might apply so much pressure through intellectual property restrictions that they successfully block these technologies, regardless of allied opinions — something the Biden administration was reluctant to do. This creates tremendous uncertainty for engineers at companies like SMIC who are trying to plan what technologies they’ll have access to over the next five years.

Jay Goldberg: One fascinating aspect is the competing factions within the Trump administration pulling in opposite directions on these issues. Some favor complete decoupling from China, while others — with Elon Musk being a prime example — remain dependent on Chinese operations.

Musk’s factory in Shanghai is central to his entire fortune. Where do his loyalties lie? He maintains influence in this administration, though perhaps it’s diminishing. Tesla relies heavily on that Shanghai gigafactory for global exports, which likely makes him more sympathetic to China.

From China’s perspective, there are approximately 56 electric vehicle companies competing with Tesla. Some, like BYD, Xpeng, and Li Auto, are beginning to surpass Tesla and would benefit from seeing it hindered or shut down. Strong voices in China oppose Tesla’s presence. If Musk can’t leverage his Washington influence to foster friendly US-China relations, what value does he provide to China? They could simply shut him down.

This situation gives me some hope that a peaceful resolution might be possible.

Bill Reinsch: Last year’s gossip suggested Chinese officials were optimistic because they believed Musk would advocate for their interests. However, it’s important to remember that everyone who has worked for Trump eventually gets sidelined — it’s just a matter of time.

When Trump was inaugurated, I predicted Musk would last six months, and I’m maintaining that prediction. His formal role might expire in May anyway, but the real question is when his influence will fade. Everyone eventually falls out of favor. There’s already speculation here about which cabinet member will be dismissed first, with various theories circulating. It’s become a parlor game.

Jordan Schneider: The one certainty we face is policy swings regarding the CHIPS Act implementation, export control regulations, and tariff structures. This level of uncertainty affects the future of initiatives begun during Trump’s first administration to revitalize domestic manufacturing.

Jay Goldberg: Some believe the tariffs are merely a negotiating tactic that will eventually lead to more reasonable levels without lasting damage. This perspective is misleading for two reasons. First, as Bill noted, we will undoubtedly end up with higher tariffs regardless of negotiations. Second, there are concerning secondary effects.

The implementation of tariffs and Chinese counter-tariffs has created a major opportunity for domestic Chinese chip design companies. Their strengths lie in trailing-edge manufacturing and analog products, with approximately 500 companies competing in this space.

Until very recently, the Chinese semiconductor industry was pessimistic — they faced excessive internal competition and geopolitical constraints. These new tariffs have made products from American companies like Texas Instruments and Analog Devices much more expensive in China, precisely when Chinese companies are releasing massive amounts of analog capacity.

This will propel several Chinese chip companies to positions where they can compete globally. Once they achieve global competitiveness — as we’ve seen many times before — they’ll disrupt foreign competitors due to their cost advantages and low capital costs. This will permanently alter the chip design landscape as Chinese champions emerge onto the global stage.

Without these tariffs, this transformation would likely have taken another five years to materialize.

Bill Reinsch: This is fundamentally a timing issue. When the October 2nd export controls were implemented, our team at CSIS identified three key questions — the effect on US company revenue, the impact on Chinese policy, and the potential “design-out” problem where companies would remove US technology to avoid control restrictions.

Regarding the second question about Chinese policy impact, your assessment is accurate. These controls didn’t change Chinese strategy, as they’ve been moving in this direction for the past decade. However, the controls have accelerated their timeline, forcing us to address these challenges much sooner than anticipated.

Jay Goldberg: The controls have pushed many sectors past the point of no return, which might not have happened otherwise. While this outcome was probable, things could have evolved differently. Now we’ll face permanent Chinese competition in several markets.

Jordan Schneider: Jay, what corporate and policy responses do you anticipate for the trailing-edge and analog sectors?

Jay Goldberg: The situation presents challenges. Companies like Texas Instruments have spent the past five years upgrading their capacity, investing approximately $10 billion to lower their cost structure, enabling them to compete with low-cost Chinese manufacturers. They’ll likely weather this storm.

However, other companies will struggle, particularly European firms like STMicroelectronics, Infineon, and NXP, as well as American companies like Analog Devices and ON Semiconductor. These organizations now face unprecedented Chinese competition in analog, memory, and several other categories. Previously, they could monitor Chinese competitors without serious concern, but now they suddenly confront formidable new rivals.

Jordan Schneider: Is there a solution through tariffs, subsidies, or industry consolidation?

Jay Goldberg: No easy answer exists. Tariffs aren’t effective because demand is primarily coming from China. The bright spot in analog chip companies’ revenues recently has been the Chinese electric vehicle market, and these companies will lose substantial portions of that business. Their growth prospects are diminishing, forcing them to lower their outlooks.

Additionally, these pressures clearly drive Chinese companies toward domestic solutions. To Bill’s point, this trend began around 2018. Chinese domestic chip consumption increases by roughly one percentage point annually. While overall market share remains in single digits, certain sectors show higher penetration.

This trend will accelerate over the next year. Once domestic competitors establish themselves, they secure more funding and cash flow, enabling increased R&D investment. This makes them more competitive and establishes them as permanent industry players in ways they wouldn’t have been otherwise.

Jordan Schneider: Jay, let’s discuss the leading edge. How do you view Intel and TSMC in relation to Huawei’s efforts to vertically integrate the entire semiconductor ecosystem?

Jay Goldberg: Regarding leading-edge technology, China still has considerable ground to cover. Despite persistent rumors about major breakthroughs, they haven’t quite reached that level yet. Their progress will likely take several more years, though the tariffs have certainly energized their efforts and accelerated the process.

Huawei remains heavily dependent on TSMC, continuously finding new channels to access TSMC wafers in a constant game of whack-a-mole that will continue. Another complicating factor is the apparent reduction in US federal government resources. How can the Bureau of Industry and Security effectively enforce existing export rules with staff shortages while other government branches face similar cuts?

Huawei and other Chinese companies continually establish shell companies and reorganize their corporate structures. This creates a tremendously tricky enforcement environment.

What confused me most this week was Trump’s apparent focus on NVIDIA as an adversary. This seems contradictory — if our goal is winning the AI race, why target the American company leading in AI computing? Hopefully, this is merely negotiating posture, but it’s perplexing.

Bill Reinsch: I agree completely. With Trump, policy often becomes personal. If he dislikes someone, that sentiment transforms into policy, making outcomes difficult to predict.

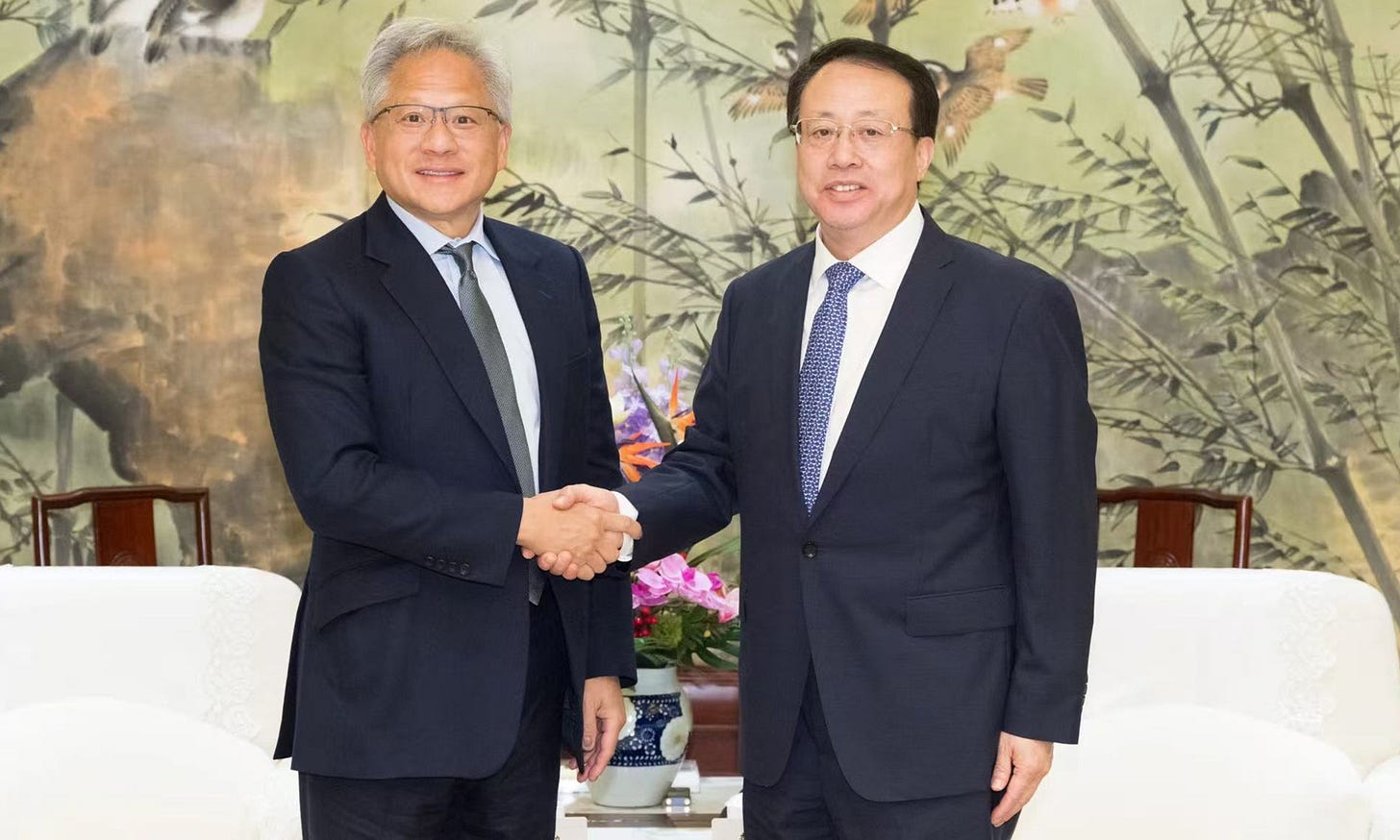

Jordan Schneider: Visiting Beijing immediately after the H20 ban and meeting with Liang Wenfang seems like an unusual choice. NVIDIA’s future isn’t in China — the administration couldn’t make that clearer. It appears to be a questionable tactical decision.

Jay Goldberg: Jensen Huang even wore a suit and tie rather than his signature leather jacket.

Bill Reinsch: He’s attempting to balance competing interests — isn’t everyone, in one way or another?

Jordan Schneider: Trump could force him to choose sides. Depending on how you calculate it — particularly regarding Malaysia — China represents between 7-15% of NVIDIA’s revenue.

Bill Reinsch: This reminds me of the 2008-2009 financial crisis discussions about banks being “too big to fail.” In this context, are certain companies too important to punish? Trump may recognize NVIDIA as such an organization. His options are limited by the consequences — if winning the AI competition requires NVIDIA, damaging the company creates substantial collateral damage that must be considered.

Jay Goldberg: Precisely. From NVIDIA’s perspective, Jensen Huang must walk a tightrope. They’ve been subtly but consistently criticizing these policies since the Biden administration because they bear the brunt of the impact. NVIDIA and ASML feel these sanctions most acutely, with each new wave costing NVIDIA billions in revenue.

Huang has quietly resisted these measures, and his Beijing visit makes this resistance more visible. His concerns are justified — China has 20-30 GPU companies that, while not currently exceptional, are improving. Additionally, Huawei demonstrates impressive AI capabilities. If Huawei maintains access to TSMC or leverages what SMIC provides, they could become a serious threat to NVIDIA.

As with analog companies, creating a market vacuum inevitably leads to Chinese competitors filling the void. Once established, they become entrenched and impossible to dislodge. NVIDIA has legitimate concerns about this dynamic.

To Bill’s point, what options exist? Undermining America’s leading AI company through tariffs or other punitive measures seems risky, even for Trump.

Jordan Schneider: The truly frustrating aspect is how long the H20 ban took to implement and its failure to address the TSMC loophole and semiconductor manufacturing equipment vulnerabilities. We’ve created a worst-case scenario where we’re inadvertently helping Huawei on both fronts by allowing them to gradually improve and market chips that compete with NVIDIA’s offerings.

Huawei has developed an impressive server rack system that, while not equivalent to Blackwell, is approaching that capability. Their product is specifically tailored for the Chinese market, where power efficiency concerns differ from ours. Instead of receiving a nuanced, optimized policy, we get the lowest common denominator approach. Even with competing objectives, we’re far from achieving optimal results because the regulatory focus emphasizes simplicity and brevity rather than effectiveness.

Jay Goldberg: Let me offer a positive suggestion since you asked for policy recommendations. We should give the Bureau of Industry and Security and the Commerce Department a thousand inspectors to enforce the existing rules. Let’s deploy adequate personnel to investigate the Malaysian companies suddenly building massive data centers.

Jordan Schneider: We could reassign those IRS employees who are reportedly being let go.

Jay Goldberg: Exactly. Shift them over.

Bill Reinsch: The 2025 budget appears to feature either cuts or no notable increases. The only substantial BIS funding increase targets the import side to address Huawei hardware entering the United States. The export control and enforcement sides have received no expansion.

A group of us produced a paper on this issue a couple of years ago, with Greg Allen joining our advocacy for budget increases. We’ve met with congressional representatives, and while our message resonates and generates sympathy, implementation never materializes.

We’re entering an era of dramatic government reduction, as Jay mentioned earlier. Proposing a 25% personnel increase for one agency seems unlikely to succeed, despite its merit.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s conclude with this, Bill. You’ve been in this field for many years, and we’re at a point where thoughtful analysis seems undervalued — yet that’s our profession. Can you offer some encouragement for those of us committed to these issues?

Bill Reinsch: I wish I could, but I’m reminded of the adage, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

I served as the staff director of the Senate Steel Caucus for 17 years, largely trying to preserve the US steel industry. This wasn’t part of my portfolio when I joined the government, but more than 20 years later, I returned to it after leaving the National Foreign Trade Council and joining a law firm representing steel companies.

I encountered one of their lobbyists and commented that I had returned after two decades. His response was telling — he said that nothing had changed other than the people involved.

This dynamic applies here as well. For 50 years, it’s been a cat-and-mouse game, which will continue indefinitely. Enforcement officials always operate defensively. The greatest mistake is expecting 100% effectiveness, which is impossible. This requires viewing it as a management problem where you optimize results within constraints.

Consider that Iran’s nuclear development efforts required 100,000 centrifuges. If your enforcement goal is zero, you’re destined to fail. If instead, you aim to limit them to 25,000 units that cost five times more and extend their timeline from three to ten years, those objectives are achievable. However, this pragmatic approach fails to satisfy political demands.

Congressional China hawks want absolute results, like seeing Huawei eliminated, banning all US-origin chips from entering China, or having ASML cease all Chinese operations. Every administration confronts this perpetually present faction that views China as an existential threat.

During the Bush administration, I had a revealing conversation with an NSC official handling this portfolio. While discussing another matter, he abruptly stated that a million Chinese wake up daily thinking about harming Americans. I responded that several Pentagon personnel similarly contemplate targeting Chinese forces — that’s their job. Without hesitation, he replied, “Not nearly enough."

These hardliners exist throughout Congress, administrations of both parties, think tanks, academia, and media. They’re currently more influential than previously. My perspective has been that the optimal policy for both nations is preventing such individuals from assuming control. I’m concerned because several now hold administration positions.

One current discussion topic is whether to implement a complete embargo, which would add little practical impact beyond existing measures but carries symbolic weight.

My outlook is pessimistic, though I hope for more measured approaches. The semiconductor industry has effectively communicated the consequences of excessive controls over the years. However, they achieved far less than they sought during the Biden administration and likely won’t fare better under the current one. Nevertheless, I commend their persistent efforts.

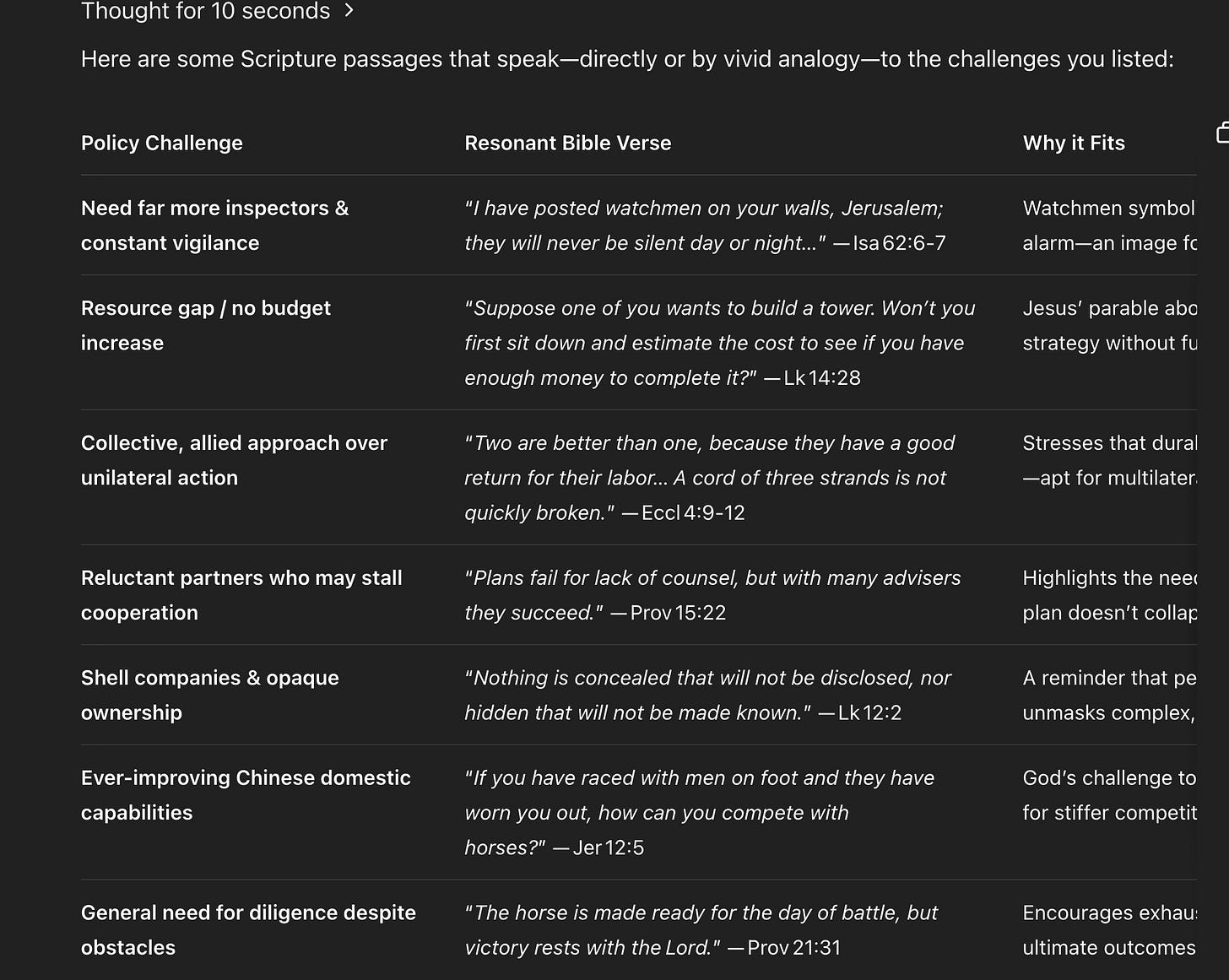

Jordan Schneider: Earlier, we mentioned that Bill’s son teaches religion at a Catholic school. I had AI generate a transcript and asked o3 for Bible quotes relevant to our discussion about BIS export controls. Bill, could you pick your favorite from the list?

Bill Reinsch: “Nothing is concealed that will not be disclosed, nor hidden that will not be made known.” Luke 12:2.

Jordan Schneider: My favorite was: “No wisdom, no understanding, no counsel can avail against the Lord. The horse is made ready for the day of battle, but victory belongs to the Lord.” So we’ll leave export control effectiveness in divine hands.

Bill Reinsch: My son would agree with that.

Jay Goldberg: “Plans fail for lack of counsel, but with many advisors, they succeed.” Proverbs 15:22. I’ll choose that one.