Is Cold War II upon us? What should America do to prevent a hot war?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Dmitri Alperovitch. Dmitri emigrated from Russia in 1994 at age 13. He is the co-founder and former CTO of the leading cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike and has spent the past four years running his new think tank, the Silverado Policy Accelerator. Dmitri brings a unique perspective to these questions as an immigrant and someone who matured professionally in the geopolitics-inflected world of cyber.

He’s the author of the new book World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century.

We discuss:

Lessons from Cold War crises that almost went nuclear;

Underappreciated parallels between the Soviet Union and China today;

Groupthink in Washington and Silicon Valley;

What a productive economic relationship with China would look like given national security concerns;

Some bold military and diplomatic recommendations for Taiwan;

… and more!

Open Philanthropy is a leading philanthropic funder focused on conventionally underrated causes. They’re hiring a new member for their Innovation Policy team, which aims to accelerate scientific and technological progress. This role will be responsible for identifying and evaluating grant opportunities, and involves working with Matt Clancy, who leads the program (and writes New Things Under the Sun, one of my favorite blogs on this topic).

This role is an excellent opportunity to contribute to projects that could potentially improve the lives of billions of people. I’ve also known Matt for half a decade, and think he’d be a great boss.

The role is remote, offers flexible work hours, and provides competitive compensation and benefits. If you have experience in metascience, innovation policy, or a related field — and you like the idea of finding high-leverage ways to boost the world’s scientific output — this role could be a perfect fit for you. (Or someone you know; Open Philanthropy offers a reward if you refer someone they hire.)

Applications close after June 30, so if this interests you, apply soon!

From Salami-Slicing to Full Invasion 蚕食鲸吞

Jordan Schneider: I want to start with the question that every normie friend of mine asks me — is Xi going to invade Taiwan? When I answer this question, I explain the contrast between Xi and Putin, but your book argues that they are actually quite similar.

One reason the two might be different involves Putin’s professional backstory. He was a spy who lucked his way into power, whereas Xi is a princeling born into aristocracy. He spent the majority of his career being a local politician, fixing potholes, and focusing on economic growth. He had only about one year on the national stage prior to becoming Hu Jintao’s Vice President.

Dmitri Alperovitch: By the way, it’s actually the same thing with Putin. He spent the 1990s serving as deputy mayor of St. Petersburg.

Jordan Schneider: There we go. The biggest difference to me, though, is less the personal backstory than what they’ve done in power.

With Putin, of course, there was blood from the very beginning, as he used the wars in Chechnya to solidify his power. He’s started or gotten himself involved in wars throughout his entire reign [Ed.: Georgia 2008, Ukraine 2014, Ukraine 2022, Syria since 2015, Libya beginning in 2017, and the Central African Republic beginning in 2018].

Whereas with Xi, we don’t have that track record. We have all of these obnoxious incursions and salami slicing, but we have nothing on the scale of the invasion of Georgia, for example. My hope is that after ten years in power, the guy might have already shown us who he is. Maybe Xi just isn’t the type of guy who’s really ready to roll the iron dice, but rather takes military adventurism more seriously than Putin.

I don’t know. Dmitri. Tell me I’m wrong.

Dmitri Alperovitch: Yeah, I think you are wrong. It’s true that Putin is much more of a gambler than Xi — I agree with you on that. But I still think that Xi is a gambler.

Xi has gambled and engaged in adventurism, whether it’s the Sierra Madre in the South China Sea, or whether it’s the confrontation with India on the border.

Or we can look at zero Covid, which was the ultimate gamble — he shut down the whole country for several years in the hopes of stopping a virus that spreads through air droplets.

The crackdown on the tech industry was another incredible gamble. Not on the scale of Ukraine 2022, of course, but Putin had never gambled on that scale before either.

All the other conflicts you mentioned — whether it’s Ukraine 2014, whether it’s Syria, or Georgia, or even Chechnya — were on a much, much smaller scale with much smaller stakes.

But appetite grows with eating, in the case of both men. As they succeed in their gambles and don’t receive pushback, they try for more. Ultimately, that’s how you end up with Ukraine 2022.

Xi clearly wants to invade Taiwan, or at least have that option. You see that from the intelligence community assessments, but you can also see it because the military buildup that he is pursuing is specifically focused on that one thing.

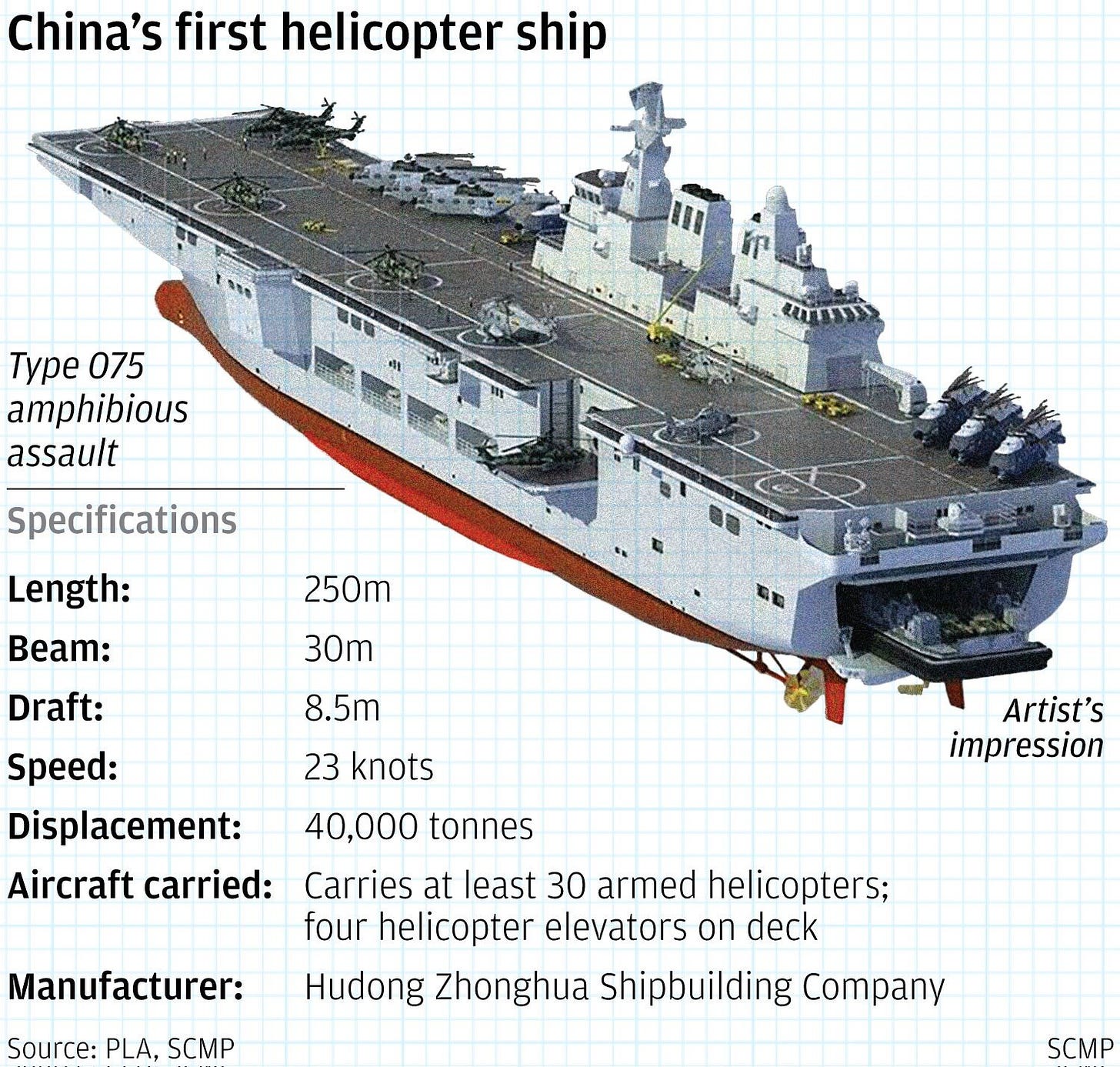

If you look at things like the mass construction of RORO ships (roll-on roll-off), the building of Yushen amphibious assault ships and helicopter landing decks — those are not for just random power projection or a blue-water navy. They’re focused on one thing and one thing only, which is taking the island of Taiwan. He talks a lot about how he’d like to do it peacefully. But the option of using force is not off the table.

He’s going to step into it cautiously, and the goal for him is to keep America out. That’s been his strategy since day one. His objective after coming into power is to increase his leverage over the US economically and decrease our leverage over him. He’s building the military capability to inflict severe losses on American forces in the region.

Jordan Schneider: I want to come back to the idea that eating increases your appetite. There are different dishes one can eat — and rolling tanks into another country feels like a very red-meat strategy. Putin has done that two and a half times, if you count Syria as a half, before really taking the biggest swing of his professional career.

Xi hasn’t seized an island, for example, which was conceivably one of his options.

Dmitri Alperovitch: That would be counterproductive and he knows that.

Jordan Schneider: Well, people do counterproductive things all the time. Xi has done counterproductive things over the past ten years.

The chance of invasion isn’t 0% of course, but do you think there is any danger in overstating the risks?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Even if there is only a 5% chance that he might do it, we must do everything in our power to make sure this doesn’t happen. Invasion of Taiwan would result in a disastrous war that would cause a global depression, and countless losses for the Taiwanese, for our allies, and for us if we get involved.

Even if the risk is small, we have to make sure that we drive it down to zero as much as possible. That needs to be the overarching focus of American foreign policy.

Victory vs Containment

Jordan Schneider: We’ve had this big debate in foreign affairs over the past week about the endgame for US-China strategy. What is your strategic vision for US policy toward China over the next 20 years?

Dmitri Alperovitch: I wrote my own piece on that endgame in Foreign Affairs, where I compare the situation in Taiwan to what was happening in West Berlin in the late 1950s, and 1960s.

We are unquestionably in a Cold War II with China.

I mean, the similarities between the two conflicts, as I write in the book, are just absolutely eerie. You’ve got a global competition for supremacy, you’ve got an ideological struggle, you’ve got an arms race, you’ve got a space race, you’ve got a spy war, you’ve got a major regional flashpoint, you’ve got economic warfare — all of which we had during the first Cold War. The one argument that people use to say we aren’t in a cold war is the existence of economic interdependence — but that’s nonsense for two reasons:

Interdependence with China is decreasing day by day via de-risking and selective decoupling. Decoupling is taking place on both sides, by the way. China has been focused on that for a decade or more — its whole basis of Made in China 2025.

This is based on a false premise and selective memory. People assume that the Soviet Union and the West had no economic dealings whatsoever. That’s wrong — there were actually massive loans given to Warsaw Pact countries to sustain their economies. The entire oil and gas industry of the Soviet Union was running off Western technology that was sold to them. They were exporting that oil and gas to Europe and elsewhere. They were exporting wheat. You had quite a bit of economic connections even during the height of the Cold War. Not the same scale as China, but the trend lines are very similar.

Given that we’re in a cold war, what is that grand strategy for victory? Just like in the first Cold War — our strategy should be containment. The goal is to avoid a hot war and prevent expansionism.

We did that very well in 1961, and before that, with West Berlin.

The Berlin Wall, as devastating as it was for people living on the Eastern side of it, was actually a good thing for the Cold War because it stabilized the most significant flashpoint. It signified that the risk of a hot conflict between America and the Soviet Union had diminished dramatically.

In fact, Kennedy celebrated the building of the Berlin Wall when he learned about it in August of 1961. He said, “Thank God, right? If they’re building the wall, Khrushchev’s definitely not invading.”

By the way, the risks of a hot war during the summer of 1961 were perhaps the greatest of the entire Cold War. Kennedy was on television the month prior telling the American public to get ready for nuclear war, asking Congress for funding for fallout shelters. He announced that the US was going to defend West Berlin at all costs, including at the risk of nuclear conflict.

Once the wall started to get built, he realized that we pulled back from the brink. The conflict stabilized. The Cold War still went on, of course. There was the war in Vietnam, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and so forth.

But the detente in the 1970s, I believe, could not have happened if there was a real daily threat of war over Berlin, as there had been since the late 1940s with the Berlin airlift and through the 1960s.

That stabilization of the conflict enabled us to get to a much better place in the Cold War. We had arms control. We could have diplomatic discussions. The competition was still quite acute, but the risk of actual conflict diminished.

We could get to the same place in China if we built a metaphorical wall — or “boiling moat,” as Matt Pottinger would call it in his book — across the Taiwan Strait. In other words, deter China from ever trying to take this island, because that is really the only place where the United States and China have the potential to go to war.

We’re not going to fight over some rocks in the South China Sea. We’re not going to fight over some rocks in the East China Sea. It is all about Taiwan. We can survive if we settle the Taiwan issue — it’s now very clear that China is a diminishing power and the United States is not.

If we can return to the state of the 1980s and 1990s, where there was not a constant fear of Chinese invasion (Third Taiwan Strait crisis aside), then we have real potential for a better relationship and economic ties.

Jordan Schneider: I’d like to quote Kennedy’s speech on the Berlin Wall that you mentioned earlier [note: this is Kennedy’s speech to the American people, not the “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech]:

It would be a mistake for others to look upon Berlin, because of its location, as a tempting target. The United States is there; the United Kingdom and France are there; the pledge of NATO is there — and the people of Berlin are there. It is as secure, in that sense, as the rest of us — for we cannot separate its safety from our own.

I hear it said that West Berlin is militarily untenable. And so was Bastogne. And so, in fact, was Stalingrad. Any dangerous spot is tenable if men — brave men — will make it so.

We do not want to fight — but we have fought before. And others in earlier times have made the same dangerous mistake of assuming that the West was too selfish and too soft and too divided to resist invasions of freedom in other lands. Those who threaten to unleash the forces of war on a dispute over West Berlin should recall the words of the ancient philosopher: “A man who causes fear cannot be free from fear.”

We cannot and will not permit the Communists to drive us out of Berlin, either gradually or by force. For the fulfillment of our pledge to that city is essential to the morale and security of Western Germany, to the unity of Western Europe, and to the faith of the entire Free World.

Rhetoric like this raises the blood and gets people really excited to compete, but it is also a fact that the two presidents that were most aggressively in favor of drawing lines in the sand were Kennedy and Reagan, and it was during their presidencies that we had our scariest moments — including this Berlin Wall crisis, but also with the Cuban missile crisis, and then with Able Archer in 1983.

My understanding of the argument that you, Pottinger, and Gallagher are making is — we are going to have a moment of crisis with China where we put our cards on the table and make the long-term national-power trajectory clear. Once we get past that, then it’s smooth sailing and we can explore a detente.

Am I reading history wrong?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Well, maybe you’re misreading Gallagher and Pottinger a little bit — because I don’t actually agree with their piece. They’re not calling for coexistence with the CCP. They’re calling for victory over the CCP, which I’m not.

I’m perfectly willing to coexist with the CCP, and I’m personally done with regime-change adventurism. I have no interest in regime change in China, nor would that be possible.

As far as misreading history, Able Archer has been pretty much discredited by documents that have come out of the Soviet Union. That this was not as dangerous of a period as people once thought. It all stems from Oleg Gordievsky’s defection. He was a KGB agent who defected to MI6 in Britain in the 1980s, and because of him, we now know a lot more about what was happening and that this was a lot less scary than has been presented.

But 1961, and obviously 1962, with the Cuban missile crisis, which originated from the West Berlin crisis, was very, very scary. But of course, it wasn’t the only time when West Berlin was a crisis. In fact, the late Eisenhower administration was dealing with this issue on a pretty much daily basis and was very concerned about the prospect of war.

Truman was dealing with it in the late 1940s with the Berlin airlift. That threat had been present in the early years of the Cold War also. It became more acute in 1961, but I don’t think it became more acute because of anything that Kennedy did, because Khrushchev was pushing his advantage.

They had that summit in Vienna, and Kennedy went into that summit wanting a better relationship. He wanted to convince Khrushchev.

He came away from Vienna shocked that Khrushchev was completely uninterested in that. The only thing that he wanted to talk about was pushing Americans and their allies out of West Berlin. And he decided that he had to make a stand and push back — which ultimately worked, because Khrushchev, of course, blinks.

After that, they had a better relationship that probably would have improved significantly had Kennedy not been assassinated in 1963. But things ultimately improved anyway with Nixon in the 1970s. That trajectory was going to take place no matter what. That’s where the similarities are their strongest.

We have a lot to learn from that period of the Cold War insofar as how to keep Cold War II cold, but also how to prevent adversaries from getting a strategic advantage.

What cards does the US have to play?

Jordan Schneider: What is striking to me is that the people I talk to nowadays who are most sanguine about America’s future are immigrants from China, immigrants from Russia, and immigrants from Iran.

Dmitri Alperovitch: Yeah. Because look: we have the unique perspective as immigrants to have lived in countries elsewhere and have come here because we think this is a much better place.

By the way, we’re not the only ones. If you look at our border — and I’m not a fan of open borders and uncontrolled immigration — but the fact that you have thousands of people literally every day trying to get across that border is an indication of something: no one is trying to get across the Chinese border and trying to live there [Ed.: other than North Koreans].

The USA is the place where people want to live to create a better life for themselves and for their children. We have unbelievable advantages in innovation, access to capital, our influence around the world in terms of our alliance networks and partners around the world, and the power of our ideas.

But that all aside, the fact is we’re still benefiting from people coming in and their children growing up and contributing to this country, as I had an opportunity to do. We have all these advantages that China does not.

I actually think China is a lot weaker than the Soviet Union was during the Cold War, and we beat them. For sure, we can beat the Chinese and make sure that this century remains an American century. But the first thing we have to do is avoid a conflict and hostile takeover of Taiwan.

Both of these would be disastrous outcomes.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah. Running through a few more of the national power benefits you’ve ticked off that we’ve also discussed on ChinaTalk in the past.

We have alliance networks, technological innovation, immigration, and a political system that is a little more flexible than your run-of-the-mill Leninist system.

Dmitri Alperovitch: By the way, access to capital is huge. I could never have started Crowdstrike anywhere else.

We raised $25 million right off the bat with PowerPoint slides. Name me a country in Europe or elsewhere where I could have done that. I couldn’t. The VC network, the private-equity network, and the fact that we have more banks per capita than anywhere else in the world — that is something that is completely underappreciated in this conversation as well.

Jordan Schneider: Absolutely. But let’s not forget our shortcomings. We’re talking about Taiwan a lot. Let’s lead with defense. You wrote:

It’s one of the world’s great ironies and, frankly, scandals that the United States blows one of the planet’s largest defense budgets, and yet also, as the Ukraine war has persisted, finds itself critically short of numerous necessary armaments.

I mean, what gives here?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Our strategy, certainly over the last twenty years and arguably even longer, has been messed up. We’ve been focused on the wrong things.

We’ve been distracted in the defense industrial base, in particular. We’ve become enamored with highly exquisite, highly capable, but incredibly expensive platforms that we can no longer afford and arguably could never afford to buy in the quantities that are necessary. And as the saying goes, quantity has a quality of its own.

We have to get back to the basics. We have to manufacture at scale.

The Ford aircraft carrier is a perfect example of this. I’m not one of those people who believe that aircraft carriers are obsolete. They’re absolutely essential for power projection. We still need them, and we’ll need them for the foreseeable future.

But we had the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, which is head and shoulders above the capabilities of any other country’s carriers. Russia doesn’t really have aircraft carriers, but it was better than China’s, better than the French carriers, you name it.

Then we decided to get an upgrade, and we went to the Ford class.

The Nimitz class cost $4 billion. The Ford class cost nearly $14 billion. I can tell you, we did not get 3.5 times the value from the Ford class. Why not stick with the Nimitz? It was perfectly fine.

$4 billion is not chump change, but with a $14 billion price tag, how many can you really afford given the state of our deficit spending and national debt?

On every level, we go for the most expensive we can get. We’ve gotten rid of the competition in the defense industrial base by consolidating it so much in the 1990s.

I write about this last supper that took place during the Clinton administration, where they brought all the defense contractor primes together and said, “You better start merging because we’re not going to be funding all of you.” All of that was a mistake and, unfortunately, led us to where we are today: where we have capability to produce one Virginia-class sub per year when we need two or two and a half, really.

Our shipbuilding capacity has been decimated. Our ability to produce munitions at scale — whether it’s javelin missiles or stingers or anti-ship missiles — is nowhere near where it needs to be. Not to mention artillery.

We know how to build these things. It’s not that hard. I’m not even advocating for increases in the defense budget.

The defense budget, $900 billion is an enormous defense budget. Now, part of it is personnel costs and other things — but nevertheless, you could take that $900 billion and spend it much more wisely.

Jordan Schneider: What’s the root cause here? Is this captured interests and political economy? Are Boeing lobbyists just that good?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Well, some of that is certainly the lobbying and the political patronage of manufacturing plants in your district. But the bigger issue that transcends actually even the defense industrial base, and you see it in semiconductor policy as well: we get enamored with the most advanced, with the highly capable.

We want to be at the leading edge of innovation. We want always to have the best that we can possibly get. And anytime someone out there invents something that is better than ours in any industry, we’re immediately screaming, “We got to catch up.”

This is our own Sputnik moment. You see this in hypersonics, which are pretty much useless as a weapon today given the cost at which they’re being procured — $60 million, roughly, for a missile. Tell me — how many targets are there that justify spending that much money?

By the way, do you know what else you can do to bypass air defenses if you don’t have hypersonics? A large number of conventional missiles. If you have 15 tomahawks that cost $2 million a pop — those can penetrate most air-defense sites because you can basically overwhelm them with your incoming strike package.

That’s still half the cost of one hypersonic. Just because China is spending all this money on hypersonics, does not mean that we need to follow them over the cliff and do the same thing until the price drops. Continue the research, but don’t procure it, because it’s just a waste of money.

But on semiconductors — and I know you've covered this in ChinaTalk a lot — we’re so enamored with tech on the leading edge. That’s all fine and good, but we’re completely forgetting about foundational chips (some call mature and legacy), which are way more important for everything. You can’t build a single unit of electronics without those chips.

Our policy is basically, “Well, China can own all that,” which is just absolutely ridiculous and a strategic threat.

The CHIPS Act allocated very, very little money to foundational chip fabs, and the Commerce Department rightly pushed back and got a little bit more, but still nothing close to what we’re spending on advanced chips.

You just see this across the board — we are so enamored with being at the very leading edge of innovation, and sometimes that is counterproductive.

Creative Diplomacy for Ukraine and Taiwan

Jordan Schneider: Dmitri, you predicted the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier than most people. Can you discuss that prediction and the ensuing chat with Jake Sullivan?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Well, I retired from Crowdstrike in 2020 and started Silverado to focus on China and Cold War II. But in late 2021, because I was still keeping an eye on Russia, I became convinced that the invasion of Ukraine was going to take place that winter.

I went public with that prediction on Twitter, and Jake Sullivan called me to discuss it. One of the things that I suggested to Jake as they were going into one of the negotiations with the Russians was to float the idea that we would abandon the open-door policy on NATO membership to Ukraine.

At the time, I justified it by saying that Biden had already ruled out sending American troops to fight for Ukraine. That rules out the core condition of Article Five – if we admit Ukraine into NATO, then we must be willing to send American troops to fight and die for the country.

It seemed like a contradictory policy to talk about that one day Ukraine will join NATO, but yet say that we’re not willing to fight for them yet. It’s not that I seriously believe that it would be enough for Putin, but I thought it would be worthwhile to explore just to gauge the Russian reaction. Of course, the Biden policy was that the open door policy stays, and they were not willing to withdraw it.

I don't think it would have been enough to deter Putin anyway.

Jordan Schneider: That makes a lot of sense. Jake Sullivan is probably the sharpest and most rational national security advisor that we could hope for. But we have a government with different sources of power and different competing interests. Our system prioritizes the free exchange of ideas over pure rationality.

Do you think the American political system can become harmonious enough to compete with China? Will we ever rationalize defense spending, industrial policy, and immigration policy? Do you think that there is a ceiling on how coherent America can be?

Dmitri Alperovitch: This incoherence is a recent phenomenon that started with Carter’s administration. This was possibly the worst period of American foreign policy ever — we had the Iran hostage crisis, and the Afghanistan invasion by the Soviets. Kissinger and Nixon get so much of the blame for opening up to China, when in reality they didn't do anything except pocket concessions.

They went over to China, and after they improved relations they immediately used that as leverage to get a detente with the Soviet Union.

Mao was livid at Kissinger. He called him a bad man in private conversations with Kim Il Sung because he thought that they were cheated. Nixon didn't reverse the recognition of Taiwan. He didn't pull the American troops out of Taiwan. Kissinger kept telling the Chinese, “We'll get to it, we'll get to it.” He said it during the Nixon era. He said the same during the Ford era.

It was Carter and Brzezinski in 1979 who decided to pay the Chinese back for the favors. They withdrew the the Mutual Defense Treaty with Taiwan. By that point, the Soviet and the Chinese relationship was already on the upswing in 1982, just three years later, it improved dramatically.

It was a complete disaster, in my view, to reopen China without any sort of guardrails, and it actually led to the situation that we have today.

We blame the Taiwanese for not having a good defense strategy.

Well, why do we think that is? Because we left 45 years ago. Not only did we leave, but we broke off all high-level contacts. No active general officer is allowed to talk to the Taiwanese officially.

They've been essentially living in a bubble for 45 years.

Carter and Brzezinski also started all this lofty rhetoric about human rights that continued into future administrations, which has really not served well.

This idea that we're going to spread freedom and democracy around the world was always hypocritical because we were in close alignment with Saudi Arabia and all kinds of nefarious dictatorships around the world.

You see this with the Biden administration when they announced their summit of democracies. They excluded Singapore, Bangladesh, and tons of potential partners in the Middle East. If you’re going to talk in terms of us-versus-them, it’s not very smart to tell countries on the fence that they ought to go to the other side because we don’t want them.

Jordan Schneider: Can you maybe reflect a little bit about how Putin was able to charm chunks of America and the EU into not caring about his invasion of Ukraine?

Dmitri Alperovitch: I don't think we should give Putin any credit for domestic polarization whatsoever.

In fact, our focus on Putin and what he did in 2016 has been counterproductive because we made him look like he's ten feet tall. He was not.

Virtually everything that has happened since 2016 in terms of divisions and the polarization of this country is our fault. Let's put the credit where it belongs – with us. Yes, there's foreign influence by Russia, China, and Iran in our elections, but it is minuscule compared to the domestic disinformation and misinformation that is spread by people on the left and the right. Of course, you can't do anything about that because of the First Amendment.

This is not a unique period of division in American history. I mean, we've had the civil war, the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement. We're nowhere near that level of division. I take solace from the fact that we've overcome all of these great challenges before.

As divided as this town is, you and I know that China is the one thing that is largely bipartisan. That's how we got the CHIPS Act passed. We got aid to Ukraine passed despite the fact that a chunk of the republican party was opposed, because we added aid for Taiwan as a sweetener.

Jordan Schneider: That’s an optimistic take. You know, I had Matt Pottinger on the show, and I asked him what Trump would do if China invaded Taiwan. It seemed like Matt was just crossing his fingers and hoping for the best.

If Trump only cares about the balance of trade and nothing else, then I don't think he’ll end up adopting most of the policies and prescriptions for Cold War 2.

Even if there is a bipartisan consensus about China, presidents have a lot of power and they set the tone for their party.

Whatever the difference between Carter, Reagan, Ford, and Nixon — they all agreed that the Soviet Union wasn't cool. In contrast, Trump seems to enjoy going to the palaces of dictators and thinks it's awesome that Putin has shiny stuff in his house.

Dmitri Alperovitch: I'm not here to defend Donald Trump, and I don't think even Donald Trump knows what he would do. Some of his policies in China were really good, and some of them were not so good.

His comments on Taiwan were quite unhelpful, at least in private. But the reality is that he's very unpredictable, and there's a positive side to this, according to madman theory.

The Soleimani assassination is a case in point — the military threw in that option unseriously, not expecting him to take it. Everyone was shocked. But in the end, it actually had a deterrent effect on Iran.

Maybe Trump would abandon Taiwan, but maybe he would fight for it and even threaten nuclear war over it. The fact that he's so unpredictable can actually unnerve the Chinese, and give them some pause. Again, there are positives and negatives here, but anyone who claims to know what Donald Trump is going to do is deluding themselves.

Jordan Schneider: Sure. Nixon was a fan of madman theory, but he knew it was an act.

Dmitri Alperovitch: Maybe it works better when it's not an act.

Jordan Schneider: I want to come back to your idea about election interference.

Putin and his bot farms certainly aren’t changing votes, but I do think that Putin has positioned himself in a way that resonates with some parts of the American public that admire him for being a strong leader.

Xi basically has not cultivated that anywhere on the planet. He has alienated nearly everyone. That wasn’t a predetermined outcome — Mao and Zhou Enlai had lots of friends and admirers.

But now there’s a bipartisan consensus and growing global consensus that China is a problem.

Do you think that post-Xi, a smarter or craftier leader with revisionist aims might play China’s cards more effectively?

Dmitri Alperovitch: There’s no question that Xi Jinping has been a gift to us.

I joke that if he's not an American agent, we should put him on the payroll, because, by God, everything he has done has been to the detriment of China and to the benefit of the United States.

He just can't help himself. The Wolf Warrior thing has not really gone away. Let me just give you one example.

I go to this Munich security conference every year. I’ve been going for a dozen years. This year, I was in a session there on supply chain resiliency.

There were Indians there, as well as Chinese, Australians, Japanese, and the Americans. It was going to be a pretty non-controversial session just talking about supply chain resiliency in light of the supply chain disruptions during COVID-19. It began with an Indian representative saying that India is open for business, manufacturing iPhones, etc.

Then the Chinese guy gets on the mic, and he starts off by saying, “The West – they're trying to divide us. They're turning us into good students and bad students, and we can't let that happen. We gotta unite together.” But then without skipping a beat, he turns away from the Indian guy – it was kind of an oval-shaped table – and faces the rest of the audience there. Then he says, “By the way, no one should be doing anything with India. We've got all the supply chains, we've got all the workers, we've got the huge markets. India's not going to help you. Come to China. Don't go to India.”

The audience's reaction was, what just happened here? Are you kidding me?

The Indian responds by saying, we might be students, but we don't need a master teacher.

The wolf warriors just can't help themselves! There wasn’t going to be any alienation between the Indians and Chinese on this topic, and yet they barreled into controversy. This happens so much because they feel so self-confident right now. They think that this is their time, that they've arrived. They're the world's greatest power, or they are about to be.

Of course, none of that is true, but as long as they keep thinking that, that's great for us, because of the Peak China hypothesis.

Self-confidence inevitably creates arrogant behavior, which is, by the way, not unique to the Chinese. God knows we've done it for many decades as well.

As far as China post-Xi — I don't think there's anything we can do to shape that whatsoever. The parlor game of trying to predict the next leader of China is interesting but completely irrelevant.

Honestly, what I worry about is Xi's term, not just because of Xi himself, but also because of the timeframe.

I believe that the period of 2028 through 2032 could be the most dangerous this century. I'm convinced that he wants to unify Taiwan under his rule due to his ego. I believe he is just like Putin in this respect – he wants to have this notch on his belt so he can go down into the pantheon of Chinese history and claim credit for it.

In 2027, he will most probably be reelected. In the second half of 2028, he will be done with the transition and appointing new people to place on the Politburo, so his hands are freed.

The rest of the world is also going to be pretty distracted in 2028.

You've got the Taiwanese elections in January and the inauguration of a potentially new president in May. You've got the Los Angeles Olympics taking place that summer – very distracting for the United States – and, of course, our own elections in November of 2028. We will face both a transition to a new president and a lame-duck legislature.

That opens up a window for him potentially. That window could close, at least in his mind, in 2032 because that's the end of this fifth term and he’ll be 79 then. He doesn't look like the healthiest person in the world to me. Who knows if he's going to be even in good shape at that point?

Whoever comes after that, is going to be facing a very different regional dynamic situation.

In the mid-2030s to early 2040s, invasion becomes next to impossible because of what the Taiwanese are doing, because of what the Japanese are doing, because of what we're doing with AUKUS and the submarines coming online.

It almost doesn't matter if it's Xi Jinping's successor that has the exact same thoughts and policies as he does.

Jordan Schneider: What is your take on putting US troops on Taiwan?

Dmitri Alperovitch: We shouldn’t be putting US troops on Taiwan anytime soon. That is very, very provocative. But if we have insight that China is literally weeks away from launching an invasion and this is the only way to deter them, then that might become a possibility at some point.

Anyone who has spent time walking around Taiwan can plainly see — this is a hellish place to invade. I would not want to be the Chinese that are planning this invasion. Right now we need to focus on other things in terms of building up Taiwanese capabilities.

We self-deter a lot of our connections with Taiwan. The fact that we can't send a general officer to Taiwan, even a one-star, to talk to them and actually walk the terrain and talk about how you would defend it – that's ridiculous.

Congress passed a law that authorizes this. What are the Chinese going to do? Are they going to stop trading with us? Are they going to invade Taiwan because we said send a one-star over? Is that more provocative than sending Speaker Pelosi, which got us absolutely nothing but an escalation in the relationships?

If you're going to do provocative things, don't do them for show, but actually do them for things that matter, such as mil-to-mil relations.

Productive Economic Engagement with China

Jordan Schneider: Can you explain your idea of unidirectional entanglement?

Dmitri Alperovitch: We should aim to increase their dependence on us and decrease our dependence on them. The dependence should be asymmetric, but we should not be decoupling from China wholesale.

Complete decoupling is impossible given the volume of trade that exists. We also can't get any of our allies on board with full decoupling. Finally, it's counterproductive because if you have no economic relations, then you actually have no leverage. We want more leverage over them to try to deter nefarious actions.

We've made a lot of mistakes throughout the 45 years of open trade with China — we enabled them by not penalizing them for IP theft and unfair trade practices. If we get back to a better relationship, we have to make sure that it's much more of an equal relationship.

I argue in the book that this century will be determined by whoever dominates in four critical technology areas: AI, biotech, space, and green energy.

AI is self-explanatory for your listeners. We're kind of leading, not by a lot – but in AI the gap is growing because of our export control policies on chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Biotech and synthetic biology include not just medical sciences, but also biomanufacturing. This will be revolutionary in the coming decades. This piggybacks off of AI to a significant degree.

Aerospace technology, particularly in low Earth orbit, will be very important. This revolution in cheap space lift capacity was pioneered by SpaceX with reusable rockets, and that’s why we’re ahead right now. Amazon will hopefully add to that soon with their Kuiper installation.

The good news is that time matters – we will have 50,000 satellites in low Earth orbit by the end of the decade. If China doesn't get their act together quickly here, there's not going to be enough space for them, because we're going to take all the slots. Whoever gets to that valuable real estate first wins by default.

The last one is green energy. On green energy, we're losing so badly, whether it's EVs or batteries, solar, wind, etc.

In addition to those four critical technologies, you have the two components that are essential for success in them, which are semiconductors and critical minerals. Again, on critical minerals, we're in terrible shape because of the processing and refining that's happening in China, as well as their attempts to acquire all these mining rights around the world.

On semiconductors, we're kind of on a knife's edge where we've done a fairly good job at limiting their ability to produce advanced chips but barely have done anything with foundational chips.

The goal here is to win the race for the 21st century in those critical technology areas, but also make sure that China is as reliant as possible in as many of those areas as possible to give us leverage. Because ultimately deterrence is about influencing the mind of one man. We don't know what's going to be sufficient, right? It could be that just military deterrence and more anti-ship and naval capabilities in the region is going to be enough, but we don't know.

The risks are so high here in terms of actual potential for war that you have to do it all, in my opinion.

Jordan Schneider: The concept of unidirectional entanglement is interesting because it acknowledges China's economic prowess. Where do we draw the line with economic engagement? In order to have unidirectional entanglement, you have to actually still sell stuff.

Dmitri Alperovitch: Let me give you an example – I'm perfectly willing to sell them almost any chip except the really advanced GPUs.

On AI – I don't want them to build AI models, but I'm perfectly willing to sell the ability for them to use our AI models under constraint guardrails. These would be conditions that say they can’t use our AI for their military or for surveillance of their own population.

But building a calendar scheduling app using chatGPT? Knock yourself out. I'm not trying to cut them off from using any of those technologies entirely.

Jordan Schneider: This is a really interesting example and something that is going to come to a head sooner rather than later.

China might quickly get access to American AI models, depending on how Apple decides to upgrade Siri to stay competitive in the Chinese market. You can't access OpenAI in China right now – you can’t access the API, you can't even access chatGPT. However, Apple appears to be considering a partnership deal with either Google or OpenAI.

Either American AI models are going to be sold to hundreds of millions of Chinese iPhone users, or Apple is going to have to make a deal with DeepSeek or SenseTime.

More likely than not, we are still going to have trade and engagement with China for the coming decade.

Dmitri Alperovitch: Absolutely. In medical research, for example, there's no reason why we can't cooperate with them to do joint research on cancer.

The vast majority of trade is not sensitive technology. By value, the number one good that we import from China is toys.

I'm perfectly willing to keep buying Chinese toys as long as they're safe.

But should we be selling them three nanometer GPUs? No. Should we be selling them any semiconductor manufacturing equipment? Absolutely not.

Our policy should be no assistance whatsoever from us or our allies to any Chinese fab at any node. No equipment, no precursor chemicals, no masks, no photoresist. Cut them off entirely and let them figure out the entire supply chain for the semiconductor production industry all on their own, which is something that no country has ever done in the history of this industry. Maybe eventually they'll get there, but that will buy us decades of time to restore the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific.

Geopolitics in Silicon Valley 不在其位,不谋其政

Jordan Schneider: It seems to me that you and Eric Schmidt are the two established tech entrepreneurs who have taken the China challenge seriously – you aren’t just tweeting about it, but you actually put your life on pause to focus on this issue. I'm curious, do you and Eric know each other? Why aren't there more people from the tech industry interested in this question?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Well I can't speak for Eric. Maybe both of us are just bored and have nothing better to do. I don't know.

But I got passionate about this because of my work in the cyber industry, starting with Aurora, which was the first time ever that the broader public realized that the Chinese were hacking into our companies, and stealing our intellectual property. That led me to start Crowdstrike to focus on this issue and try to protect the American industrial base from – what I called at the time – the greatest transfer of wealth in history.

The more I looked, the more that I realized that even back in 2010 we were in a confrontation with both economic and national security stakes. I became very convinced early on that we were in a cold war that no one was taking seriously.

I remember I was in a sitting room in the White House after one of my earlier reports back in 2011 days, highlighting what the Chinese were doing in yet another sector where they had stolen all this intellectual property. I was pounding the table asking them to pay attention, but the response I got was basically, “Meh, as long as they keep stealing, they can't innovate.”

It’s so incredibly racist to think that we're somehow better than the Chinese and that they can't innovate. But it’s also just historically inaccurate — I know from my background in the Soviet Union that you can absolutely steal and innovate at the same time. The Soviets stole the designs for the atomic bomb from the Manhattan Project, but they famously got to the hydrogen bomb all on their own with Sakharov developing really great innovations there.

This has happened in a whole slew of areas, like EW for example, where they stole technologies initially, but then built up incredible capabilities that have exceeded ours.

This idea that we didn't have to confront China and that we would always be ahead was just so dumb. It was incredibly naive and condescending, frankly, to the Chinese people.

Cyber was a great gateway to this because you're dealing with every industry, whether it's defense, national security technology, or agriculture — and you're seeing the real-world impact of Chinese intrusions. You're tracking back to what they're doing when they're trying to steal this data and how it's benefiting their own domestic industries and defense industrial base.

Industry experience gave me a front-row seat to all of this. That made me passionate enough that I decided to focus on geopolitics full-time once I retired from Crowdstrike.

Eric was there during the days of Aurora. He's been focused very much on AI for the last half-decade, which probably contributed to his eye-opening experience vis-a-vis China.

As far as why there aren’t more geopolitics-focused tech people – the tech industry is focused on tech. Precious few of them care about geopolitics. It's actually quite remarkable.

Some do, and there are more in cyber than in other industries. Peter Thiel cares, and Joe Lonsdale cares. But many people just want to solve problems and not care about the world, and they think that technology is the answer to everything.

I'm not of that view. I believe that geopolitics matter a great deal. As the saying goes, if you're not interested in geopolitics, geopolitics is interested in you. But you have this very myopic view sometimes in the valley, where people are not paying attention to anything that happens in Washington, much less in China.

Jordan Schneider: Another thing that people don't really price in — ideas are expensive, but upgrades are cheap. Silverado has an annual budget near $2 million, and SCSP’s budget is mid eight figures.

There's a lot of alpha here, isn't there, Dimitri?

Dmitri Alperovitch: I think so. But again, you only see it if you care about geopolitics.

Some people care, but do they think about that every day? I do, because I'm an immigrant to this country. It's been incredibly good to me. I owe a lot of my success to this country. I want to make sure that that remains for future generations.

I serve on the Homeland Security Advisory Council for the Department of Homeland Security. One of the people serving with me is the founder of Chobani. He is an immigrant like me and also very, very passionate about this issue.

Now he makes yogurt. It's not a national security resource. But because of his background, he cares deeply about those national security issues.

Jordan Schneider: People from industry give lots of money to political campaigns — why do you think they care about domestic politics but not foreign policy?

Dmitri Alperovitch: People have different priorities. Joe Lonsdale, for example, he shares my views on China. But, you know, if you look at how he's spending most of his time and his philanthropic dollars, he started this organization called Cicero.

It's focused on domestic policies such as improving education, and that's a great goal. It's great that in America we don't all have to toe the party line and we can spend our resources on the things that we think are most important.

Jordan Schneider: The Ford and Rockefeller foundations centered a lot of their giving and thinking around questions of global competition. But then again, Ford had to die for that to happen, too.

Dmitri Alperovitch: Not all of us can be doing ChinaTalk, Jordan.

Jordan Schneider: Dmitri, you mentioned industrial espionage earlier.

I predict that as soon as China gets ahead of the US in a technology we want, we'll stop being precious about not doing industrial espionage. Do you have a take on that?

Dmitri Alperovitch: I've argued for 15 years – if you can't beat them, join them. And they do have intellectual property.

I'm not a fan of moralistic foreign policy. We need to be focused on our hardcore interests. I'm a realist at heart.

But there are practical concerns around being able to do this.

We don't have one state champion. If you steal intellectual property, who do you give it to?

Jordan Schneider: Let’s give it to the Chobani guy. I trust him!

Dmitri Alperovitch: Also, culturally, our intelligence community is very, very distanced from the private sector in almost every area. Now, if it becomes existential, we'll probably figure it out. But there's a lot of resistance, both on moralistic grounds that this is sort of beneath us to steal someone's IP, which I don't subscribe to. But more practically, how do you actually do it?

Jordan Schneider: Dmitri, do you have any anthropological observations about these mythical 300 people in Washington who decide foreign policy?

Dmitri Alperovitch: There's a lot of groupthink, for sure. A lot of resistance to new ideas and elitism, too. I've been asked before, “Aren't you the cyber guy? What right do you have to speak on China?”

Jordan Schneider: Is it reasonable to expect, you know, the model waits for GPT-6 to be secure?

Dmitri Alperovitch: It's going to be really, really difficult. It's code. It's a file. Particularly when you think about the resources of a major nation-state being applied to this problem, it looks bleak.

We're not really treating this as a national security resource.

If we believe AI is revolutionary, we should treat it the same way that we treat nuclear weapon designs.

Anyone that touches it should be polygraphed, we should be protecting data centers with guns and certainly applying all of our federal resources to the vetting of the employees at these companies. We’re not doing any of that.

The government isn’t even helping these companies vet Chinese nationals. They may have families there that could get coerced, and is the DOJ helping to address that issue? No. Not yet.

Jordan Schneider: This is the trade-off, though. We are a nation of immigrants.

Yeah, and it's really tricky. Like, you probably saw this Bloomberg article about Chinese graduate students who are doing innocuous scientific research and being stopped at the border. I worry that policies like that will scare off future founders and genius AI researchers. We need some serious cost-benefit analysis of the risks of militarizing algorithmic AI research too soon vs too late.

Dmitri Alperovitch: This is true. We need to welcome immigrants to help us develop these capabilities.

There are plenty of Chinese nationals that have come here, immigrated, become citizens, and now work in the IC. I've met many of these professionals who are really, really terrific. But you go through vetting, you go through polygraphs, you go through background checks, counterintelligence checks, and then you become trusted, and you become a member of the community, and you contribute to it.

We may want to think about that model for this very specific issue of developing AI models if we think that this is really going to be a groundbreaking, revolutionary, world-changing technology.

I came out as a skeptic initially on AI, in part because I've spent a lot of my life doing machine learning and saw the limitations of that.

But deep learning and where these neural networks have come with the transformers and so forth really are game-changing, and I have to admit that. Bad people doing nefarious things even just with the models we have now is a problem that I worry a lot about.

If we really want to stop Chinese progress in this area, or at least make sure they're far behind us, we need to treat this as a national secret.

Jordan Schneider: Do you have sociological takes on the cyber security industry?

Dmitri Alperovitch: I have been saying for the past 15 years: we don't have a “cyber problem” — we have a China-Russia-Iran-North Korea problem. There is a preoccupation with cyber in isolation, and that has actually been detrimental to the field. You see this now in the Ukraine conflict — cyber is an enabler. It has some terrific capabilities, particularly in the area of espionage.

My friend General Michael Hayden, the former director of NSA NCI, said that cyber has brought us to a golden age of signals intelligence. The capabilities are no longer just passively intercepting radio signals and tapping into telecommunications cables. Now, you can actually go to the source of the data, get into the computer, and see the drafts as they're being made.

However, the ability of cyber to affect war has been way, way overstated. Ideas like “Cyber Pearl Harbor” or “Cyber 9/11” are just ridiculous, because we're much more resilient to cyber events than most people think.

Attacks can cause temporary disruptions, but it's hard to have long-term consequences because of cyber because, at the end of the day, you can always turn the computer off or disconnect. You can rebuild and be back online. Resiliency is underappreciated in my opinion, as we see from the conditions the Ukrainians are facing every day.

Spending time with the Ukrainians over the course of this war has been really illuminating. Humans have the ability to survive in really terrible conditions, with no electricity and no running water, and still remain unwilling to give up.

My new piece in War on the Rocks argues that Taiwan isn’t going to surrender in a blockade scenario.

First of all, things are not even going to get that dire in Taiwan with a blockade. Economically, things will be bad, but they have self-sufficiency in food.

Statistics show that they import a lot of food, but most of that is beef coming from the United States. Beef isn’t a staple commodity and you can survive without it. They have plenty of rice production, as well as an abundance of fruits and vegetables. They're not going to be starving to death.

Energy is a problem, as they import 98% of their energy. But it's a tropical climate. They're not going to be freezing to death like the Ukrainians are.

This idea that the minute there's a blockade, they're just going to surrender and cheerfully walk into concentration camps for re-education is just utter nonsense.

We don't appreciate the resiliency of people across the world, really not unique to any country, of being able to adapt to terrible conditions.

Back to cyber — understanding the motivations of your adversary is essential, so attribution is really important. I got so much crap for that from the entire cyber field – people used to say that attribution is impossible.

Well, we know now it's not impossible. It never has been impossible, it’s just that some cybersecurity people didn’t care where attacks came from. They just wanted to focus on blocking attacks, hunker down, and write code.

That's like saying, “Who cares where the missile is flying from? We only care about understanding the characteristics of the missile so that we can shoot it down.”

That’s important too, but the origin of an attack gives you valuable information about what else may be coming.

As more and more people from the intelligence community and from law enforcement have joined the profession, the mindset about attribution has begun to shift.

But there are still a lot of people who come to cyber from a purely technical background. They just want to work with the bits and bytes, build code, and ignore geopolitics.

Jordan Schneider: Dmitri, you're only 43. What do you want to be when you grow up?

Dmitri Alperovitch: In 2032, I'd like to write a book about how the Cold War was won.

My focus for the foreseeable future will be trying to avoid a hot war and trying to make sure that this century remains an American century. If one day I can say that has been accomplished, then that’s great. I'll find something else to do.

Jordan Schneider: Can you give a moment from Cold War history where you would have loved to be a fly on the wall?

Dmitri Alperovitch: Oh, boy. The 1961 period is not as studied as the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

For those 13 days in October of 1962, it seems like we know minute-by-minute what was happening. But as we discussed, I actually think that the 1961 Berlin crisis was just as dangerous – if not more dangerous – and it’s mostly been forgotten. I would like to know in detail how the Kennedy administration was approaching this, and how they came to this decision to defend West Berlin at all costs. We're just scratching the surface of understanding that. On the soviet side, I’d like to be a fly on the wall of Khrushchev’s Kremlin.

My friend Sergey Radchenko just wrote this terrific book – To Run the World: The Kremlin's Cold War Bid for Global Power – using declassified Soviet documents.

I've seen some portions of that book, but I'm hoping to see it highlight how Khrushchev made the decision to pull back during the Berlin crisis and recommend the building of the wall.

It was biting my tongue the entire episode listening to Dmitri war hawk on China, paint broad mischaracterizing strokes, and choose only specific examples that supported his point of view. I could hear Jordan doing the same. This episode really highlighted for me Jordan’s incredible job as a host and interviewer.