Guest column by Jacob Feldgoise, a Junior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Later this morning, President Biden will sign the "CHIPS and Science Act of 2022"—a massive bill intended to boost America’s innovation competitiveness. While most coverage has understandably focused on the “chips” half of the bill—$52 billion in appropriations to bolster the U.S. semiconductor industry—the “science” provisions could be even more transformative.

The bill seeks to direct more research funding towards underrepresented regions, protect research from IP theft, upgrade the National Labs, and much more, but the most important change might be the Tech Directorate. Congress aims to support U.S. innovation by building an applied research and commercialization division—a Tech Directorate—in the National Science Foundation (NSF). The Tech Directorate will fund applied research and commercialization activities in a bid to simultaneously diffuse the benefits of critical and emerging technologies into the U.S. economy and boost American technological competitiveness with China.

Duelling Visions on the Hill

The final iteration of the Tech Directorate reflects a compromise between the House and Senate tech competition bills that has been over a year in the making. Differences in approach between the House and Senate reflected different diagnoses of the problem. The Senate, worried that U.S. leadership in key technology areas “is under pressure from China and is eroding,” sought to strengthen U.S. competitiveness. The House, concerned that the NSF’s research was too theoretical, sought to increase the NSF’s contributions to societal challenges such as climate change and public health. Both chambers wanted to create a Tech Directorate that would bolster U.S. applied research and workforce development for key technologies, but due in part to different diagnoses of the problem, the House and Senate disagreed about legislative specificity and “authorization” levels for the Tech Directorate. Since the Tech Directorate is a substantial policy change, Congress would use this first bill to “authorize” spending, which would then still have to be appropriated in the next budget cycle.

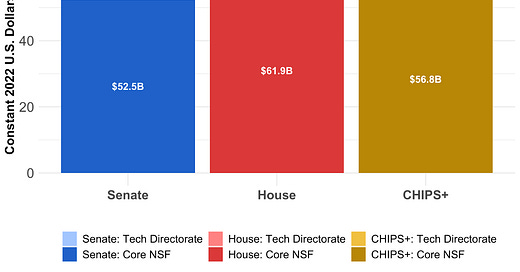

The Senate proposed a larger, more independent Tech Directorate. Senate drafters carefully prescribed the programs they wanted the Tech Directorate to run—giving the directorate far less flexibility on the details. This appeared to be an effort to insulate the directorate and prevent the rest of the NSF from redirecting Tech Directorate funding towards existing basic science programs. The Senate authorized $25 billion (constant 2022 dollars) over five years to the Tech Directorate, which would bring the directorate up to 44% of the NSF’s total budget by 2027.

The House proposed a smaller Tech Directorate that would be woven into the NSF’s existing work and would be given the flexibility to experiment with the details of each program. The drafters worried that the NSF’s existing divisions would see a large, independent Tech Directorate as a threat—one that would redirect funding away from basic science, the NSF’s core mission, towards the shiny new thing: applied research. House staffers aimed to assuage the NSF’s concerns by having the new directorate work closely with existing programs and by boosting funding for the rest of the Foundation. The House authorized $13 billion over five years to the Tech Directorate—half the Senate’s proposal—which would keep the directorate under 20% of the NSF’s total budget.

To realize any of their ambitions, the two chambers first needed to compromise. The Senate passed its innovation competitiveness bill—the Innovation and Competition Act (USICA)—back in June 2021, but the House had other priorities. Eight months later, in February 2022, the House finally responded with the America COMPETES Act—setting the stage for a conference committee that would work for months to reconcile the two bills.

In late July, as negotiations over the two bills dragged on and fears emerged that the whole effort would fail, Congressional leadership decided to change its tack. Leadership determined that a slimmed-down bill—only containing subsidies for the semiconductor industry and authorizations for a few science agencies—could pass on its own. They decided to pass these popular provisions quickly and revisit the rest later. The strategy succeeded: the CHIPS and Science Act (nicknamed “CHIPS+”) passed the Senate and House in quick succession on July 27-28, sending chip subsidies, the NSF Tech Directorate (officially the Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships Directorate), and other science provisions to Biden’s desk.

Reaching compromise

The bones of each Tech Directorate program can be found in the original House and Senate bills. The CHIPS and Science Act tasked the directorate to fund consortia of research institutions that will develop and commercialize key technologies (Regional Innovation Engines and Translation Accelerators). The directorate will also support workforce development by awarding scholarships and fellowships, fund capacity-building grants to help universities commercialize academic research, and fund R&D grants in key technology areas.

Most of these programs are based on the Senate bill with some tweaks from the House. Since programs in the Senate bill were carefully prescribed, so too were most programs in the CHIPS and Science Act—giving the NSF less wiggle room on the details.

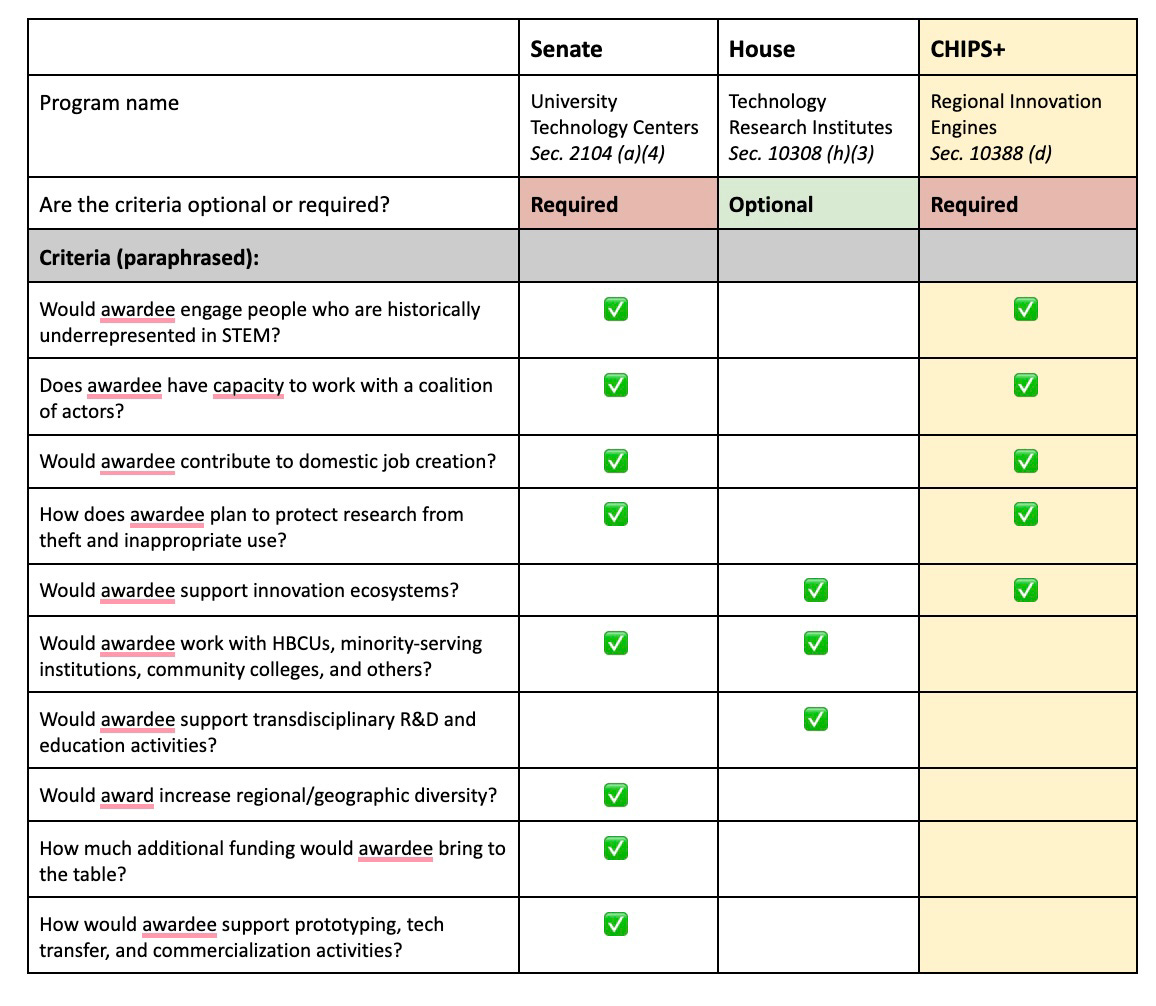

For example, the Senate provided less flexibility than the House on how to award innovation center grants. The Senate included a list of criteria that the NSF must consider when selecting a center. By contrast, the House offered a list of criteria that the NSF may consider—letting the Foundation make the final call. The CHIPS and Science Act leans closer to the Senate’s approach by providing a shorter but mandatory list of criteria.

Prescribing priorities this detailed is a double-edged sword. Congress is more likely to get what they asked for, but the NSF will also have less flexibility as it spins up new funds for applied research and commercialization.

Table 1: Criteria for Awarding Innovation Center Grants

The Tech Directorate will be authorized for more funding than the House originally proposed but less than the Senate wanted. The Tech Directorate will be authorized for $19 billion (constant 2022 dollars) over the next five years—about halfway between the House and Senate proposals of $13 billion and $25 billion, respectively (Figure 2).

In total, the CHIPS and Science Act will authorize NSF for about $76 billion over the next five years—in between the House and Senate proposals of $74 billion and $77 billion, respectively.

Finally, the Tech Directorate’s mission statement respects the divergent motivations of the Senate and House but does not reconcile them. The statement has three pieces:

The House's ambitions to increase the NSF’s role in use-inspired research for societal good,

The Senate’s ambitions to strengthen U.S. tech competitiveness, and

The goal expressed by both chambers to support workforce development in key technologies.

How the Tech Directorate decides to prioritize the three components of its mission statement will shape key attributes of the directorate, such as how it will allocate core R&D funds. For now, the directorate’s priority mission is unknown.

Congress has teed up a potentially transformative Tech Directorate, but without sustained support, this effort will fail. The U.S. has often struggled to maintain critical, long-term investments, and this is especially true for industrial policies. The erosion of U.S. technology leadership in sectors such as chip fabrication is partially attributable to the U.S. government’s unwillingness to match the investments of its competitors and sustain them. Similarly, the Tech Directorate can only bolster U.S. innovation competitiveness if Congress gives it the resources to do so. To avoid reliving the cautionary tale of chip fabrication, Congress must be willing to fully fund the Tech Directorate in the current budget cycle and sustain that investment for decades to come.

Do any of these bill specifically incentivize or disincentivize firms already fully beholden to China for manufacturing or component supply (Apple, WalMart, Tesla, etc)?

Do you have any planned posts on the Chinese economic situation? Or recommendations for credible folks who cover that topic area?

I realize this is totally orthogonal to your post but there's a lot of potential insolvency issues which will have meaningful government interventions.