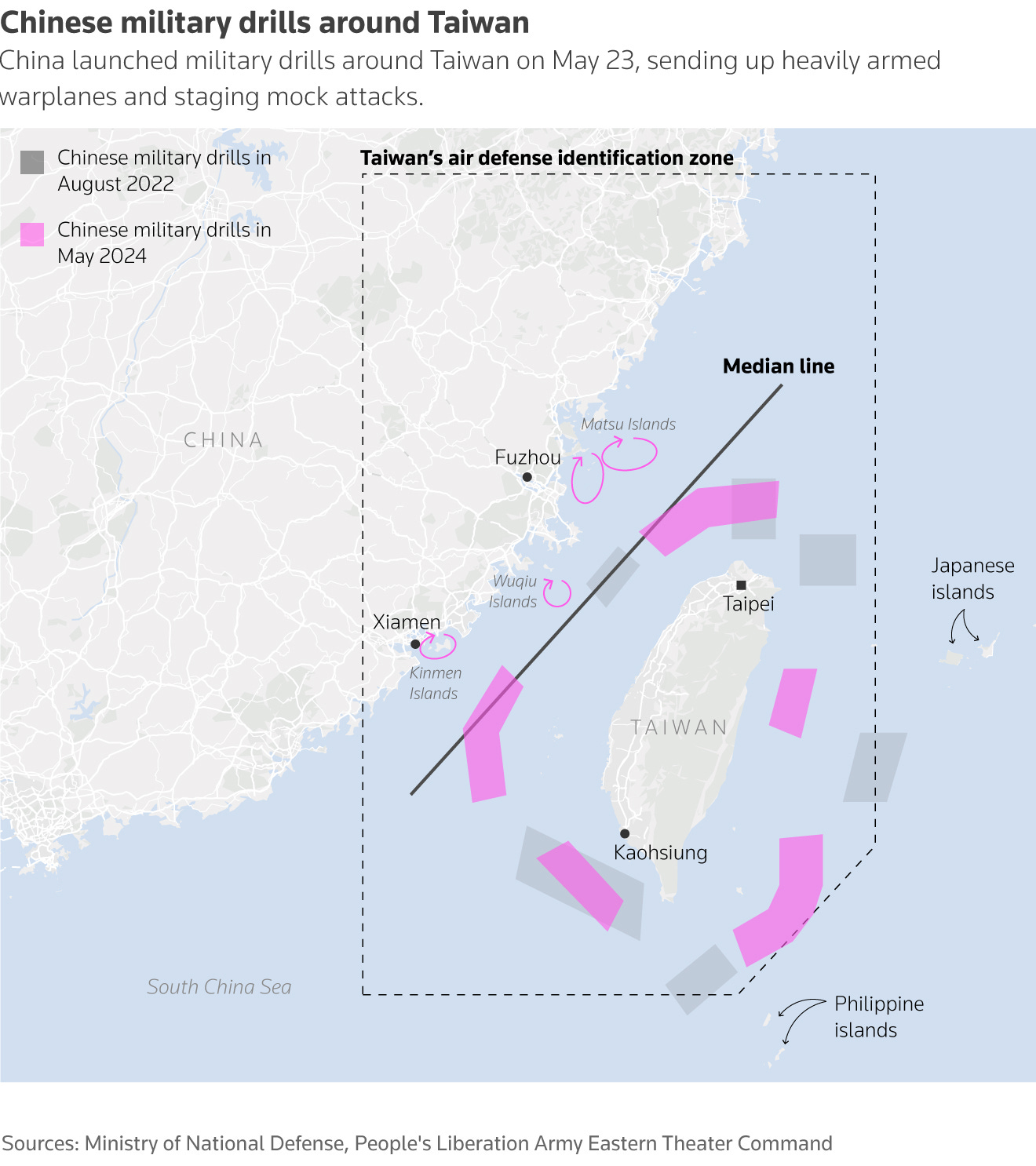

Taiwan’s government agencies are battered by 5 million cyberattacks every day. China is holding invasion drills at a replica of Taiwan’s presidential palace in Inner Mongolia. Last week, the PLA openly rehearsed an encirclement of Taiwan in so-called “punishment drills.”

What happened to deterrence in the Taiwan Strait? Can the status quo be saved?

To discuss strategies for avoiding WWIII, ChinaTalk interviewed Jared McKinney of the Air War College and Peter Harris of Colorado State University, who recently co-authored a monograph entitled, “Deterrence Gap: Avoiding War in the Taiwan Strait.”

Co-hosting today is ChinaTalk editor Nicholas Welch.

We discuss…

Why deterrence is decaying;

The difference between constraints and restraints in a deterrence strategy;

Whether symbolic solidarity with Taiwan does more harm than good;

The values and costs of strategic ambiguity;

Indicators of a successful deterrence architecture, as well as falsifiable and objective measures to test hypotheses in political science;

… and more!

Collapsing Constraints and Incentives to Invade

Jordan Schneider: Can you start by explaining the history of Taiwan deterrence, and why you think it’s faltering now?

Jared McKinney: The mood in Taiwan, with a few false invasion warnings aside, seems to be one of the status quo. Sometimes, Taiwanese people will say that Taiwan has been under threat from the PRC since the late 1940s. They think, “If we’ve had scares for the past seventy years, why should we be unusually afraid today?”

They understand that the PRC is a threat, but it’s been a threat for a long time.

Part of this is true and part of it is not true. Contrary to many people’s interpretations of the past, Taiwan was in a pretty secure position from the late 1950s to the early 2000s. In fact, from the mid-1950s to about 2004, a PRC invasion of Taiwan could not have happened. It would have been sunk in the strait. There would have been the proverbial million-man swim, and Taiwan would remain de facto independent.

This secure position was enabled by a combination of Taiwanese and American military power. People tend to talk a lot about American military power, and of course that’s a real factor — but they tend to minimize Taiwanese military power during this period, which is a big mistake.

In terms of American military power — after the Korean War, we became de facto engaged in the defense of Taiwan from a communist invasion, and then de jure or formally engaged in the defense of Taiwan from a Chinese invasion with the 1954 Mutual Defense Treaty onward. As a result of the de facto and then de jure commitment, we interposed US naval power regularly in the Taiwan Strait in a dedicated unit called the Taiwan Strait Patrol. We station tens of thousands of US soldiers in Taiwan.

Later on in the Cold War, we actually put tactical nuclear weapons there — a fact that is now declassified. We had a formal commitment. We backed up the commitment. And then there were two crises in which China signaled some aggressive intent in 1954 and 1958. Both times, we threatened nuclear war in response to PRC saber-rattling. Nuclear war was not something China was interested in, especially since China didn’t have nuclear weapons until 1964. Those were some pretty robust deterrents, even if there were some scares in this period.

Usually, when people talk about preventing war, they discuss deterrence, but we think that it’s actually more useful to think about deterrents.

Taiwan’s deterrents played a significant role during this period — for example, Taiwan’s air power.

Guess who got the first air-to-air kills in the history of air combat using precision-guided weapons? It wasn’t the United States. It was the Republic of China Air Force in 1958, which fired Sidewinder missiles to shoot down PLA fighters in the strait. They achieved kill ratios of about 30:4.

The PLA wasn’t competitive because they were firing guns and trying to do dogfights. They were being shot down by the seeking missiles that the US had transferred or sold to Taiwan.

The Republic of China Air Force at the time was awesome. Maybe it could have even stopped an invading Chinese force on its own — but it was never on its own because we had multiple interlocking deterrents at the time.

Even though people like Mao were borderline crazy, deterrence was basically assured.

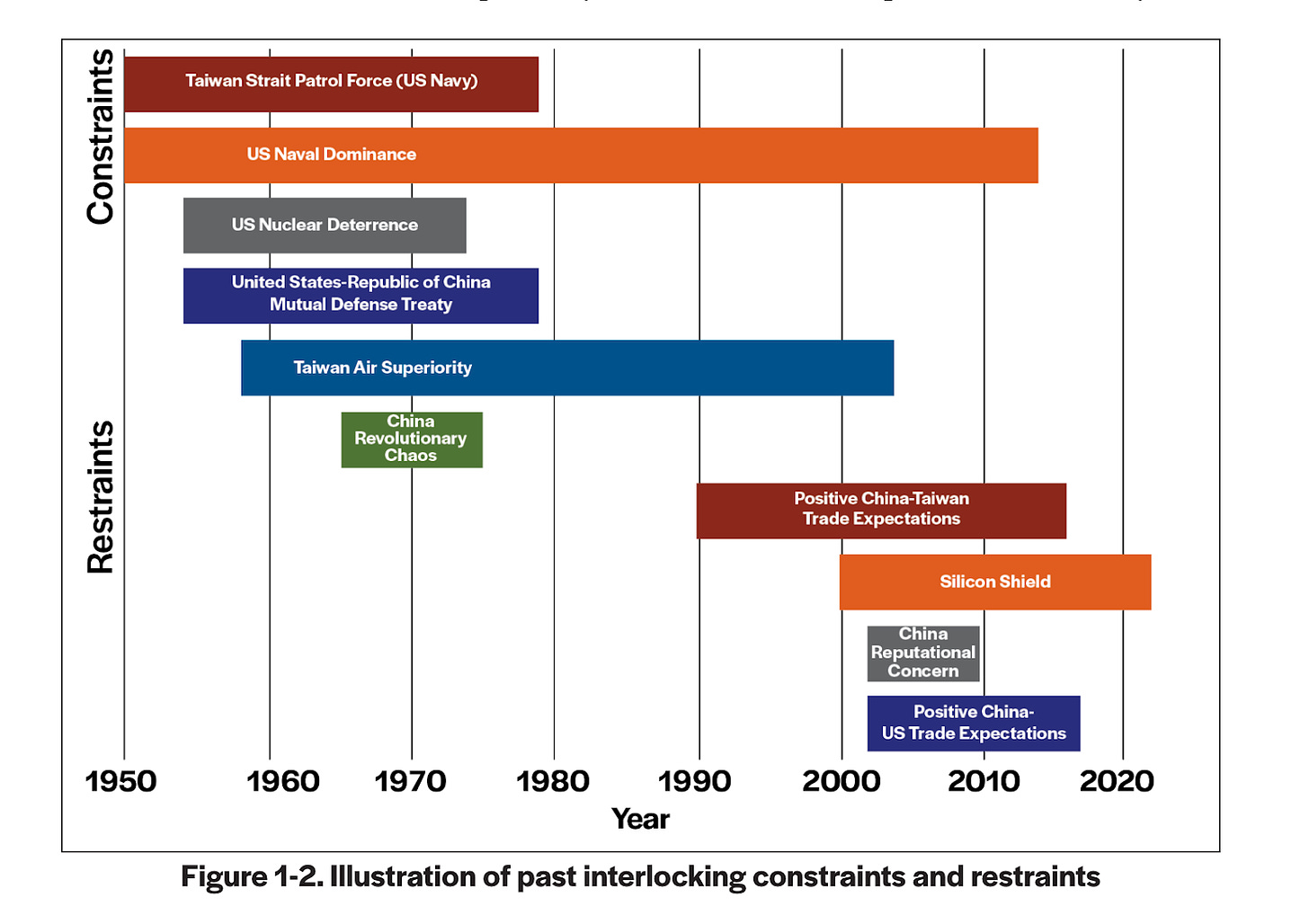

Nicholas Welch: One thing I liked about your monograph was the bifurcation of deterrence into constraints versus restraints. Can you talk about what that adds to our understanding of deterrence?

Jared McKinney: In very simple terms, a constraint is something prohibiting you from doing something or limiting your ability to do it — while a restraint is something internal to your own mind, prohibiting or limiting you from doing something.

Supposedly, my car has the capability to drive 120 miles an hour. But there are restraints preventing me from driving that fast: I don’t want to hurt anyone, I don’t want to kill myself, I don’t want to go to jail.

In the context of deterrence, there is actually similar logic in which people sometimes choose not to do things even though they have the capability to do so. If you have a holistic deterrence equation, you need to look at not only imposing constraints, but also creating incentives for acting with restraint.

Nicholas Welch: When looking at the interlocking constraints and restraints, it’s very striking how in the twentieth century, the US and Taiwan relied almost exclusively on constraints like US naval dominance, nuclear deterrence, and Taiwanese air superiority.

Then, at the turn of the century, most of those constraints disappeared, and now we almost exclusively rely on restraints like China’s positive expectations about trade with Taiwan and the US, or Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturing capabilities.

Can you talk a little bit about why the twentieth century was so constraint-heavy and what’s changed going into the twenty-first century?

Jared McKinney: Before the rapprochement with China in the 1970s, there weren’t a lot of positive incentives in the relationship. It was hard-nosed deterrence focused on constraints.

However, once we go through this process of rapprochement in the 1970s, the potential for positive incentives is created. This is true for first the United States and then for Taiwan itself, which, beginning in the 1990s, begins a relationship with the mainland that deepens and widens — starting with sending mail back and forth, and then widening out to include tour groups and trade. Then, a relationship of technological interdependence emerged in the 2000s, centered on Taiwan’s silicon industry.

Peter Harris: Leaders in Taiwan have also made policy mistakes. They should have invested more in the military in the 1990s and 2000s to maintain that external lock. It was a mistake to rely upon self-restraint on behalf of Chinese leaders.

Because you never know. The difficulty with deterrence is that it’s really hard to find observable implications that deterrence is working. You never really know what is deterring an adversary from pursuing an undesirable action.

It’s prudent to make sure that there are as many layers of deterrents as possible. Even if you think, or you hope, that economic interdependence or Chinese concern for their reputation or something is working to restrain them, it’s still prudent to maintain those external locks.

Jared McKinney: In the mid-1990s, Taiwan was spending 5%+ of its GDP on defense. Then that number fell to below 2% until recently. Then in the last two years, it’s gone a bit above 2%, maybe heading in the direction of 2.5%.

That’s the right direction, but there’s a lag time between investment and actually procuring military power.

Jordan Schneider: It’s certainly easier to spend money on a military when you’re a military dictatorship.

Jordan Schneider: Figuring out what drives people’s decisions is a fascinating and impossible question.

Can you explain the trends that you believe are the most worrisome regarding deterrence today?

Jared McKinney: A big problem with the current discussion on Taiwan is that we don't know what’s in Xi Jinping's head. We don’t know how exactly China interprets many trends. We don’t know if we’re reading information about the PRC correctly. It is a mistake, I think, to approach the topic with too much confidence.

We want to push people to analyze ideas in a way in which they can be falsified.

As part of our argument, we lay out at the end of the book how we could be proven wrong. We’re watching for that evidence as it emerges. We actually have nine indicators, and we would be willing to reverse our position if the majority of them prove false.

This doesn’t mean that we’re going to be able to establish scientific certainty. But I think that this approach moves us away from just fear-mongering.

The problem with fear-mongering is you can cry wolf only so many times before everyone stops believing you. We believe that the constraints that externally bound the PRC have mostly decayed.

The term “decay” shows that deterrence is a temporal thing. You can establish it for a while, but then an adversary can try to circumvent what you have threatened them with. Deterrence decay has actually happened in a sort of quantifiable way.

Taiwan’s Air Force was superior to China’s until 2004. Today, Taiwan still has more or less the same air force, though the F-16s have been updated a bit.

In contrast, the PLA has fifth-generation fighters, advanced air defense systems, advanced naval SAMs, KJ 500s, and flying airborne radars, all of which pose a lethal threat to fourth-generation fighters.

That constraint has decayed. It’s been circumvented. The same happened with American military power.

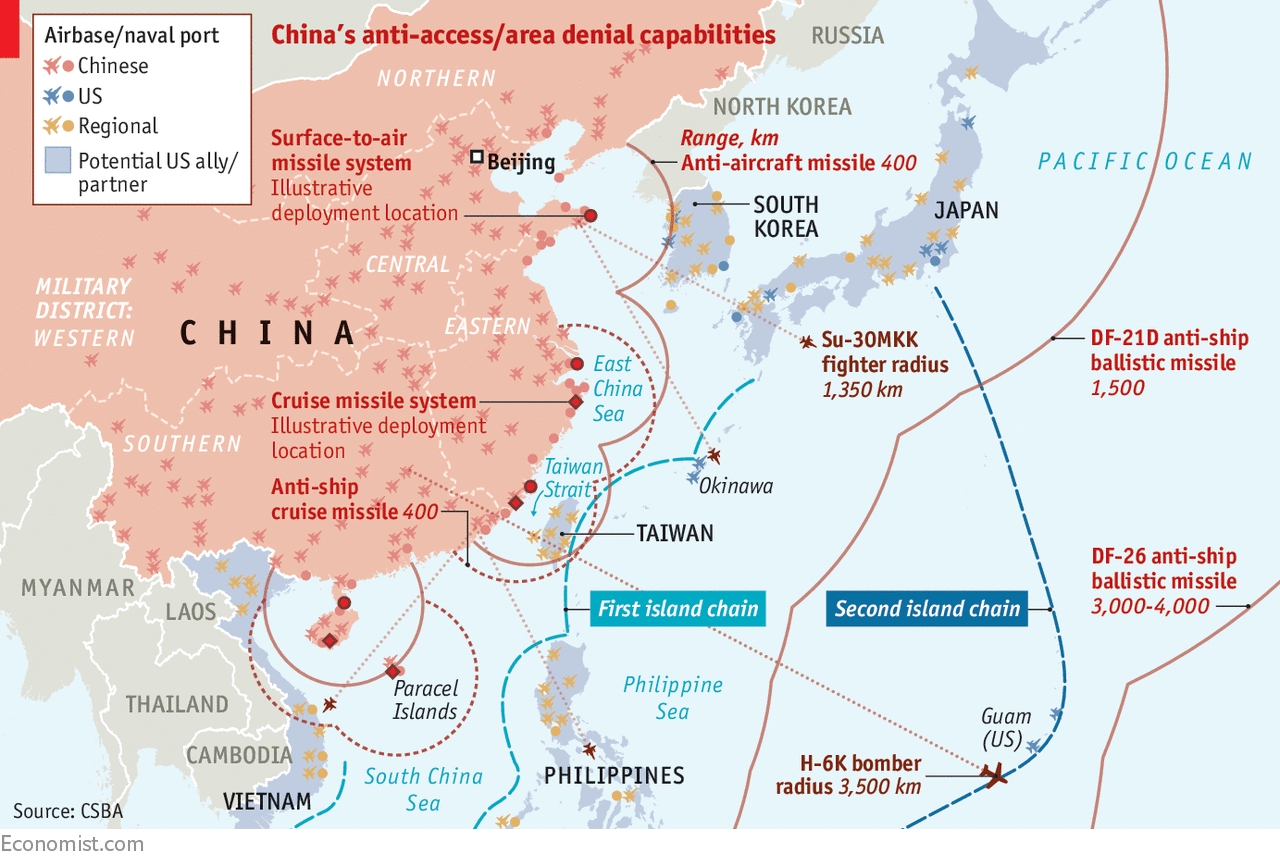

There used to be a consensus that if China invaded Taiwan, the US would just send in the aircraft carriers with F-18s.

Now, the PRC has circumvented the default American response. Starting in the 1990s, the PRC developed and eventually deployed an anti-access area denial capability that’s based on missiles which can kill aircraft carriers.

We’re in a position today where naval-borne air power is no longer relevant as a deterrent.

If constraints have mostly disappeared, then what about restraints?

The restraints are those elements that could incentivize the PRC to maintain the status quo. For example, Revolutionary chaos in China used to be a powerful constraint. During the Cultural Revolution, people talked to Mao — Nixon, Kissinger wanted to know whether China was planning to invade Taiwan. Mao essentially says, “There’s a bunch of counter-revolutionaries there. Why would we want to invade? We have enough counter-revolutionaries at home.”

In Deng Xiaoping’s 1984 “One Country, Two Systems” speech, he says, “It could take 100 years or it could take a thousand years, but peaceful unification is the way forward for Taiwan.”

A thousand-year timeline gives the Communist Party a lot of time to act with restraint — but that’s gone now. The PRC’s third historical resolution from 2021 changed that timeframe to 100 years, starting from 1949.

It literally says that the objective is to complete the complete reunification of the Chinese nation by the 100th anniversary of the founding of the PRC. There’s a cognitive shift from broad acceptance of a very long timeline for peaceful unification, towards a deadline that is only a few decades away.

These time pressures are concerning in that they indicate a certain inevitability about forceful unification that wasn’t present before.

Ambiguous Strategery, Symbolic Solidarity, and the End (?) of One China

Nicholas Welch: You identify that, since the turn of the century, there have been four restraints in particular which have been trending in the wrong direction. One of those indicators is the One China policy. Can you explain why One China is important for deterrence?

Peter Harris: In order for the PRC to opt against invasion, the status quo needs to be barely tolerable. There’s always a cost of restraint as well as a cost of war.

For a long time, the status quo across the Taiwan Strait has been more or less stable because of this One China discourse. Obviously, there’s a wide range of disagreement between the United States, Taiwan, and China over what the phrase “One China” means.

But this constellation of understandings about “One China” created a kind of middle ground, where leaders in all three polities could agree for a long time that the political status quo was tolerable.

From the PRC’s perspective, what that meant was there was no international move toward recognizing Taiwan as an independent and sovereign state, especially not in Washington, DC. Thus, to forego the option of invading Taiwan was not tantamount to de jure losing Taiwan.

This was based on a theoretical possibility that everyone was at least nominally open to the possibility of peaceful unification in the future. We go back and forth about how realistic that has truly been.

But we think that has changed.

One reason it’s changed is because of changing Taiwanese domestic politics, which the United States cannot control.

But more importantly for our monograph, there’s a perception in Beijing — not an unreasonable perception — that America’s One China discourse might be shifting. That gives cause for concern in Beijing. It creates an incentive for Chinese leaders to start thinking about a resolution to the problem. If the status quo is not stable, what are we moving toward?

They fear that the status quo is trending toward a future where an American leader brings Taiwan back under the American security umbrella. A “Two Chinas” policy or a “One China, One Taiwan” policy is not tolerable for Beijing.

Nicholas Welch: You mention “27 Firsts” that American leaders have done with regard to Taiwan.

For example, Trump picked up a call from Tsai Ing-wen before he took office. John Bolton met the secretary-general of Taiwan’s National Security Council. Taiwanese admiral Lee Hsi-min 李喜明 came to the White House in 2019.

You argue that these things obviously piss off the CCP and make it less inclined to believe the West’s commitment to a one-China principle.

What would you say to the argument that those “firsts” are beneficial? Is it possible that they strengthened the resolve of the Taiwanese people to resist invasion?

Jared McKinney: The resolve to fight for freedom is internally derived and not externally given.

America can’t breathe life into Taiwanese de facto independence. That’s something that Taiwan and its people are going to have to believe in.

Peter Harris: Even if we assumed for a moment that that would stiffen the resolve of Taiwanese people, it would come at the cost of convincing Chinese leaders that the status quo had already been overturned.

The better approach would be to find ways to stiffen Taiwanese resolve to convince China of Taiwan’s commitment.

Jared McKinney: We need substance, not symbolism. The truth is that most of these interactions are almost purely symbolic.

The problem with symbolism is that it antagonizes the PRC. It pushes against the established framework, but does nothing to actually contribute to Taiwan's ability to defend itself.

Jordan Schneider: The two big variables here are Taiwan’s willingness to fight and America’s willingness to show up. Biden has said concretely that if China invades, then the US will put boots on the ground. The defense of that choice was to strengthen the belief that the US would show up, and bank on that as a deterrent.

What’s your take on the tradeoffs inherent in strategic ambiguity?

Jared McKinney: We argue that you get a better deterrent effect from ambiguity than you get from clarity.

If the PRC believes that America is very likely to intervene in an invasion of Taiwan, then the PRC would very likely will launch a first strike against forward-deployed American units, logistics, fifth-generation fighters, and destroyers. This first strike would do a lot of damage and create a pause in American military power which could potentially be exploited and snowball into a successful invasion.

If the PRC doesn’t know what we’re going to do, then they won’t launch a first strike. They’d load up 30,000 soldiers in amphibious vessels — 071s, 075s, ROROs — and send them out into the Taiwan Strait.

At that moment, if we chose to intervene, we could sink them all. If we did that, then in fact no invasion of Taiwan would be possible. But the PRC will get to that point of vulnerability only if they don't know what we’re going to do and thus decide not to launch a first strike.

Jordan Schneider: The counterargument is that the probability of those ships going into the water goes down if the PRC is certain that an invasion means WWIII against the USA.

Jared McKinney: Military commanders want certainty, especially in the PLA.

They’re not comfortable with tons of uncertainty. How do you report uncertainty to your commanding officers? Your answer, in reality, is that an invasion might be catastrophic or it might be okay. From a military commander’s point of view, that’s not very acceptable.

If you can generate uncertainty about the overall operational success, I tend to think that’s the more salient view variable. Even though there could be a larger war, a military commander is focused on that operational point of view.

Peter Harris: Even if we accepted the premise about strategic clarity bolstering deterrence, that would still be a mistake for the Taiwanese above all else, because what if we have a future president, like Trump or someone after him, who says that they wouldn’t come to defend Taiwan? Or, a war in Europe or the Middle East could cause China to start to doubt whether the United States can muster the capability.

Thus, to rely too much on that US-led deterrent would be a mistake. One of the lessons from Ukraine was that it’s much better to engage in a general, direct deterrence. For Taiwan, that means maintaining a standing array of autonomous deterrents that it can level against China.

I want to push back against the idea that only the threat of a cataclysmic world war is sufficient to deter the Chinese invasion of Taiwan. I just don’t agree with that. I think there are less serious threats that can be leveled against China that are serious enough to make an invasion irrational and to stop one from happening.

Those deterrents can come from Taiwan and regional partners. They don’t need to be US-led.

Richard Haas and David Sacks wrote this article in Foreign Affairs entitled “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous.” It was very sober and kind of an arresting article, but there was a line in it where they said, yes, fighting China over Taiwan will be devastating for the United States even if we won. But they argued that we should threaten that anyway.

But I think it’s incumbent upon people who argue for that to then also explain how we are supposed to make that credible. We’re admitting that it would be devastating for us to fight a war against China, even if we win. That decreases the credibility of our threat to start that war, even in the best of times.

Because the usual commitment devices are not possible in the case of Taiwan — we cannot sign a treaty or permanently forward-deploy US forces on the island. If I were Taiwanese, I would probably prefer deterrence to be built upon a foundation that doesn’t depend on who is occupying the White House next year, in five years, or in ten years.

Making war is difficult, yet making peace is not easy 战难和亦不易

Nicholas Welch: Even if all the constraints and restraints have basically disappeared, what hasn’t changed is how insanely difficult it is to pull off the invasion.

Tanks don't walk on water. Boats aren’t hypersonic. The Taiwan Strait hasn’t gotten any narrower. Taiwan hasn’t built more landing beaches for the PLA.

The longer Xi stays in power, the more different Taiwan becomes and the harder it gets to swallow. Just like Mao said, Taiwan is not desirable.

Peter Harris: While it’s true that the geography has not changed, China is more capable than they were twenty years ago, and the costs of restraint have changed. The more American leaders talk about Taiwan as this democratic outpost that is essential to the defense of the Indo-Pacific, a critical node in America, the more the costs of restraint increase.

“Oh gosh, the Americans, they’ve changed the way they think about Taiwan. Even though it’s not becoming any easier to seize Taiwan by force, it’s become more important to pull the trigger ASAP — because if we don’t, we’re going to wake up in five to ten years’ time and the US will have recognized an independent Taiwan and brought it back under its security umbrella.”

— The CCP, maybe

Jared McKinney: The truth is that an invasion would be incredibly hard — and we actually have good evidence for why.

But this difficulty can be made even harder with relative ease. That’s where we would disagree with Brands and Beckley.

We’ve read articles recently saying we need to spend 5% of our GDP on defense to get ready for this challenge. We’ve read an article saying we need to threaten a preemptive nuclear war against China if they suggest they’re going to invade Taiwan.

We disagree with all of that. We think deterrence can be restored much more easily.

One of my brilliant army students [coming soon to ChinaTalk!] did a year-long investigation of America’s plan to invade Japanese-occupied Formosa in 1944. This was known as Operation Causeway.

At the time, the US calculated that we needed 3:1 force ratios to successfully take the island. There were 98,000 Japanese soldiers on the island, which meant that we needed close to 300,000 soldiers to land on Formosa in order to defeat the Japanese.

Today, there are 169,000 soldiers in Taiwan’s military. There’s also the potential for reserves, but their quality is unknown, so we’ll stick with 169,000 as our estimate.

If you do similar force ratios today, we’re talking about half a million PLA soldiers on the island. Given the PLA’s lift capacity including civilian assets like ROROs, achieving that number of boots on the ground requires moving 50,000 troops onto the island per day. The truth is, in war, many of those are going to be killed, and you’re not going to be able to land soldiers that quickly.

We chose not to invade Formosa because the costs of such an invasion were too high. We think that objective assessment of similar variables today should lead to the same conclusion by the CCP. However, we’re not in the minds of Chinese decision-makers, and we don’t know how they weigh different variables.

Now, how do we make an invasion harder? We should learn the very obvious lessons of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, and invest in twenty-first-century capabilities like drones, mobile missiles, and artillery. Older technologies like mines will need to be deployed en masse.

Taiwan has more than a million people who’ve done their conscript duty — they are in a theoretical reserve. If you can turn the theoretical reserve into a real reserve, then a successful invasion actually becomes impossible, because if you take 1.5 million reserve soldiers plus almost 200,000 active soldiers, then China would need to land 6 million people to be successful. That’s larger than the whole PLA.

Singapore's model is an excellent example of how this could be done. Shang-su Wu 吳尚蘇, a Taiwanese scholar, wrote a book on Singapore’s national service system, how it works, and how it could be applied in Taiwan.

That would achieve robust deterrence. It doesn’t require radically changing the status quo in the US-China relationship.

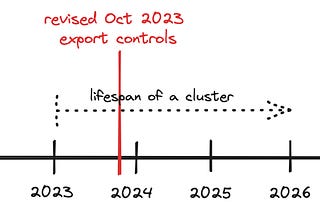

The most important takeaway in terms of military capabilities, is that we need to make sure we’re staggering them in phases. In other words, we just need to be very careful of our timelines so that there aren’t decade-long deterrence gaps. We should think of deterrence on a sort of year-by-year basis.

The Peak China Hypothesis and Military Modernization

Nicholas Welch: Hal Brands and Michael Beckley argued in their book Danger Zone that China’s window of opportunity is closing because their economic trajectory doesn't look super good. Thus, it’s either now or never to invade Taiwan.

Do you agree with that argument?

Jared McKinney: Yes. But there’s an important nuance with that argument related to military modernization cycles.

Beginning in the 1990s, the PRC began a long-term modernization project. It didn’t actually bear fruit until about 2014. This led many people to underestimate Chinese military power.

While this was happening, Taiwan was in its authoritarian-to-democratic transition and was refocusing on basically domestic politics. America was embroiled in its wars in the Middle East.

China completed this long-term program, and now we see that they are producing something like 100 J-20s (歼-20) per year, modernized support aircraft like KJ-500s (空警-500) and KJ-2000s, and they’ve built a very sophisticated navy with advanced air-defense systems and serious strike options. They’ve done things that even the US hasn’t done, like putting anti-ship ballistic missiles on to naval vessels, according to the DoD report to Congress in 2023.

Now, the United States and Taiwan are counter-modernizing against these capabilities. China’s cycle took about fifteen years. That’s probably how long our cycle is going to take.

Our counter-modernization programs include:

The B-21, which is supposed to be able to penetrate A2AD-defended airspace;

The Columbia-class submarine, which is going to be the greatest submarine in the world when it comes out;

New army and Marine Corps capabilities, including modeling some of China’s new capabilities.

All of these will come online around 2030.

Meanwhile, Taiwan is modernizing its military. It’s moved from four months to one year of conscription. It’s raising its military budget, and it’s looking to acquire some new capabilities that could pose a more serious threat to the PLA. All of that is going to take time as well.

The same story is happening in Japan. The Japanese self-defense force is modernizing with the goal of becoming a master counter-strike organization by 2030. That means, if Japan is struck, they will be able to respond with equivalent weapons. This is going to pose actually a very significant deterrent long term and is going to offer much better protection to forward-deployed US forces in Japan.

The problem with all of the counter-modernization activities is not that they’re happening, but they’re happening on a timeline that’s pretty far in the future.

At the same time, China is at a pretty good place in its modernization program. It’s possible that Chinese decision-makers could decide that now is better than later. We saw similar logic in Germany in 1914, which was driven by the military modernization programs of Germany’s adversaries.

They saw that the Russian army was going to be a million men by 1917. Germany plugged that data into their gonkulator and decided that they couldn’t win a two-front war against both France and Russia if Russia had an army of a million men.

Jordan Schneider: We had Michael O’Hanlon on the show about a year and a half ago. He wrote this fun paper where he tried to run some gonkulator calculations on whether the US could defeat a Chinese invasion.

My takeaway was that China would need the probability of success to be really high in order for them to act to change the status quo. Regardless of who’s got the coolest fighter jets, the biggest downside is still the multi-trillion-dollar economic losses.

I think it would be really hard for decision-makers in Beijing to talk themselves into the “three days to take Kyiv” pitfall the way that Putin did.

My sense is that the scariest thing from the PRC perspective might actually be having the war take longer than they had hoped.

Jared McKinney: I think we agree that the best solution for the PRC is to drop the talk about reunification by 2049 and go back to Deng Xiaoping’s thousand-year timeline.

But you can read the third historical resolution, and it says that they intend to reunify Taiwan. Whether they meant it or not, I am not sure. But they did say it. My suggestion would be to stop saying it.

Maybe Xi could give a speech on strategic patience and focus on the long game, like Deng.

The Risks of Accidental Escalation

Jordan Schneider: Your book, while convincing, sort of punts the awkward political logic of entanglement, which seems pretty relevant given the new developments in the dance of death between Iran and Israel.

That hasn’t led to armageddon yet, thankfully, but there are plenty of scary historical parallels.

Another scary parallel that comes to mind is the logic of Bush #2’s invasion of Iraq. The fantastic book Japan 1941 documents how no one in Japan ever made the decision to go to war with the US, but everyone in the bureaucracy sleep-walked forward into escalation anyway.

It’s awkward to be the one to dissent in a bureaucracy. Nobody wants to be the person who walks up to the theater commander and says, “This is actually a f*cking terrible idea.”

What does the escalation ladder look like if the PLA starts with something modest like a blockade? Could it potentially spiral into a situation where Beijing decision-makers feel like they are locked in and no one has any choice but to double down?

Peter Harris: The important thing to remember is that there will be crises in the Taiwan Strait. We can be pretty confident of that due to the unpredictability of domestic politics in the US, Taiwan, and China.

The question is, “How do you get to a dynamic that disincentivizes that kind of gradual autopilot escalation?” There needs to be confidence in those moments that if the CCP does de-escalate, they’re not going to bear some terrible cost by backing down.

In crisis moments, leaders fear that if they don’t seize the present moment to do something, then they’ll lose that opportunity in the future or suffer enormous future costs.

Regarding Iran and Israel — I was really concerned at one point over the past few days that Israeli leaders would respond to Iran’s strike by striking Iran’s nuclear facilities.

I could imagine the conversations inside the corridors of power, where some hawk says, “This is the moment. This is our only chance to retaliate against Iran’s nuclear sites. We’ll enjoy regional support, and we’ve got a good excuse or pretext because Iran just struck us. It’s a once-in-a-generation moment.”

That didn’t happen, thank goodness — but why not? War was avoided, I assume, because inside those corridors of power in Israel, they had confidence that they didn’t need to escalate to that level. They felt confident that their post-crisis survival was already assured.

You need that kind of dynamic across the Taiwan Strait. When a crisis happens, it’s important that Chinese leaders don’t feel pressure to move due to fear of losing out on the time-sensitive opportunity to peacefully unify with Taiwan.

It’s really important that the political and diplomatic foundations are robust enough to withstand those crises. We have to make clear that peaceful unification is a theoretical possibility to the future.

You need deterrence in a situation like this — your deterrents are the cap on escalation. They are the ceiling above which escalation triggers a catastrophic event. That event doesn’t necessarily need to be WWIII or the threat of a preemptive nuclear strike by the USA.

If Taiwan itself can adopt a military posture that just makes invasion prohibitively costly for the PRC, then you can combine these two pieces to see that the costs of restraint are not too serious, but the costs of war are very serious.

Face Politics, Xi Mania, and Recommended Reading

Jordan Schneider: In the book Chiang Kai-shek’s Politics of Shame, I learned that Chiang Kai-shek kept a diary for essentially his entire life. This diary had different columns to write daily updates on things like family, country, politics, exercise, what I ate, the weather … but then there’s a column called Japan and national shame. Then after fleeing to Taiwan, he starts a column on Taiwan and national shame.

I worry about dynamics like ego, manhood, and losing face 丢脸 in the One China dynamic. Everyone knows Taiwan’s been its own thing since 1949, but that’s not a fun fact for Chinese leaders to acknowledge.

Thus far, we’ve been talking about decision trees and game theory in a very rational way. But how can we analyze the risks of invasion if the decision to invade is going to be an irrational one? How can we make sure these military leaders can still sleep at night if they decide against going to war?

Jared McKinney: A lot of those issues were probably engaged with Nancy Pelosi’s vision to Taiwan in 2022. Pelosi’s visit was technically not a new incident because Speakers of the House had visited before. But when Speaker Newt Gingrich visited Taiwan, he did it in a way that actually gave face to China.

Gingrich visited the mainland first, and he met with important leaders there. Then he made a quick visit to Taiwan, he didn’t spend the night, and he didn’t talk about Taiwan versus China issues at all. He focused on positive aspects of the relationship.

On the other hand, Speaker Pelosi’s visit espoused democracy versus authoritarianism, freedom versus communism — it was very zero-sum. That’s just throwing fuel on the fire 推波助瀾 — and there is no need to take that approach.

Peter Harris: There’s at least some polling evidence that ordinary Taiwanese understand this dynamic. People in Taiwan express a little frustration or anxiety when US leaders take steps that can be perceived as incendiary or unhelpful. Everyone’s security is improved when everyone is content.

Pompeo’s idea of putting China in its proper place — there’s no way that can be construed in a constructive way. It’s just not useful discourse.

But I certainly understand there’s a danger of going too far in the other direction and being too sympathetic to the Chinese position. The United States shouldn’t rhetorically capitulate and go too far. But I agree that there’s a huge risk to trying to humiliate and to force China to kowtow 磕頭 into submission. That may well backfire.

Jordan Schneider: My recommended reading on the subject — The Consequences of Humiliation: Anger and Status in World Politics, by Joslyn Barnhart [full show on this book coming soon to ChinaTalk].

Jared McKinney: I recommend Democracy in China: The Coming Crisis, by Ci Jiwei 慈继伟. He’s a professor in Hong Kong, and wrote this book in 2019 as he watched the protests in Hong Kong unfold.

This book is a letter to the Chinese Communist Party, arguing that it’s in the interest of the party to reform and introduce democratic elements. He argues that a CCP that refuses to reform is dooming itself to a future secession crisis. He doesn’t make a moralistic argument, but rather uses logic that he hoped could persuade the party.

Nicholas Welch: Here’s a quote from that book — perhaps a one-paragraph summary of the point he’s trying to make:

[T]here is simply nowhere for the [Chinese Communist Party] to hide when the economy is not doing well or doing less well than before. This means that the Chinese party-state cannot speak of economic crises in the same way Western democratic governments can. In [the Westerners’] strict sense, economic crises are serious disturbances of a market economy conceived of as an autonomous system and, as such, presuppose a degree of separation between system integration and sociopolitical integration that is simply absent in China. For this reason, every crisis in China that otherwise resembles an economic crisis is directly a political crisis. The [Chinese Communist Party’s] role is so defined that it cannot convince anyone that “it no longer rules”— including over the economy.

Peter Harris: Individuals worry about things like shame and regret. Those emotions are part of what drives PRC leaders. They don’t want to lose a war, but they care about other things, too. They care about their political legacy. They care about national greatness. You can manipulate that or you can leverage that in service of stability and the status quo.

Jared McKinney: The reason why this is really important is because there’s a Xi-mania when it comes to understanding China.

The problem is, nobody actually knows what Xi is actually feeling in his heart. Actually, his method of ruling China is to avoid coherent guidance, because if you avoid coherent guidance, then all the decisions have to be brought to you. That means you get to micromanage things because you actually haven’t empowered people based on principled objectives.

For example, on one hand, Xi talks about increasing self-reliance. On the other hand, he talks about increasing trade. Which one is it?

The way to avoid Xi mania is to look at factors that can actually be tested. The important thing is to construct a falsifiable argument.

We suggest nine of these factors.

One such factor — are Chinese commentators optimistic or pessimistic about peaceful unification in the long term? For comparison on this metric, we look at the essay by Jiang Shigong 强世功 back in 2005. At the time, he was an optimist about Taiwan, and he actually identifies some metrics that could be used to achieve peaceful unification. Are Chinese intellectuals still optimists today?

Another measurable variable — as Chinese economic growth slows, is Chinese military growth going to slow as well? In reality, Chinese economic growth was probably close to zero last year. But the Chinese military is still growing pretty robustly, at around 7% of GDP. So it looks like so far, military growth is probably exceeding economic growth.

But that’s something we will continue to watch in the future.

Another variable — will China actually develop the capabilities needed for an invasion? People talk about 2027 a lot, but that date is mostly just tied to Xi being irritated that the PLA doesn’t actually have the sufficient amphibious lift capability to achieve a successful invasion. It seems as though he set this deadline to light a fire under the PLA. But there are other related technologies that you would need for an invasion. Are these being prioritized?

We’ve already discussed the variable of time and relative power. If we see Chinese leaders start emphasizing the idea of strategic patience, that would be a positive sign. We should watch for signs that they are starting to loosen the 2049 timeline.

It will be important to watch the results of Taiwan’s elections in 2028. In 2024, the TPP and the KMT failed to form a coalition, and that resulted in their defeat despite winning 60% of the vote. But in China’s eyes, a 60% vote against the DPP is quite a showing.

If that is replicated in 2028, that might suggest that peaceful relations could be extended further in the future.

TL;DR — there are objective variables that aren’t just trying to get inside Xi’s head, that we can try to measure one way or another to get a sense for whether we’re wrong about the urgency of the present moment.

Jordan Schneider: But Jared — wouldn’t the optimal play for Xi be to spend three years talking about patience and 1,000-year timelines, and then launch a secret surprise strike?

Jared McKinney: I mean, yes. But that’s why we need to combine rhetorical information with information about what’s happening with China's military spending or how distracted the US is in any other theater of war.

Jordan Schneider: What are your book recommendations for our readers?

Peter Harris: My first recommendation is Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley, by political sociologist John Geventas.

This is a great book for people who want to study unobservable things — which is often what you’re doing when you study deterrence. He looks at the exercise of power over people, which is invisible, right up until the moment it bubbles up and has observable implications.

This book changed the way I think about politics and the world, and it’s not even about international relations. It's about an Appalachian coal-mining town.

Jared McKinney: Yasheng Huang’s 黄亚生 new book, The Rise and Fall of the EAST, challenged a lot of my preconceived notions about China. He puts Keju 科舉 — China’s Imperial examination system — at the center of Chinese History.

He argues that the Keju allowed the Chinese state to promulgate uniformity and grow to an increasingly large scale. The super-scaled state was strong but anemic, because the exam system incentivized uniformity, disincentivized creativity, and it channeled lots of ambitious people in the same area to become bureaucrats for the government.

He argues that in periods when the examination system was more open to creativity, there was more innovation in China. But in periods in which the examination system became highly uniform and you had to write essays in a certain way, like in the Qing dynasty, China stopped inventing.

He explains that this legacy lives on today in China and the gaokao 高考 system.

Thank you. What a sobering read. I certainly hope deterrence can be reinforced and can be enough to prevent such a disaster.