The Biden administration is cracking down on compute smuggling with an export control encore! How will this new regulation impact global data center construction? What does it mean to be a Universal Verified End User? Will SMIC swoop in and fill the compute vacuum?

To find out, we brought on Lennart Heim from RAND, Jimmy Goodrich consultant for RAND and fellow at CSIS and UCSD, Chip War author Chris Miller, and Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis.

We discuss…

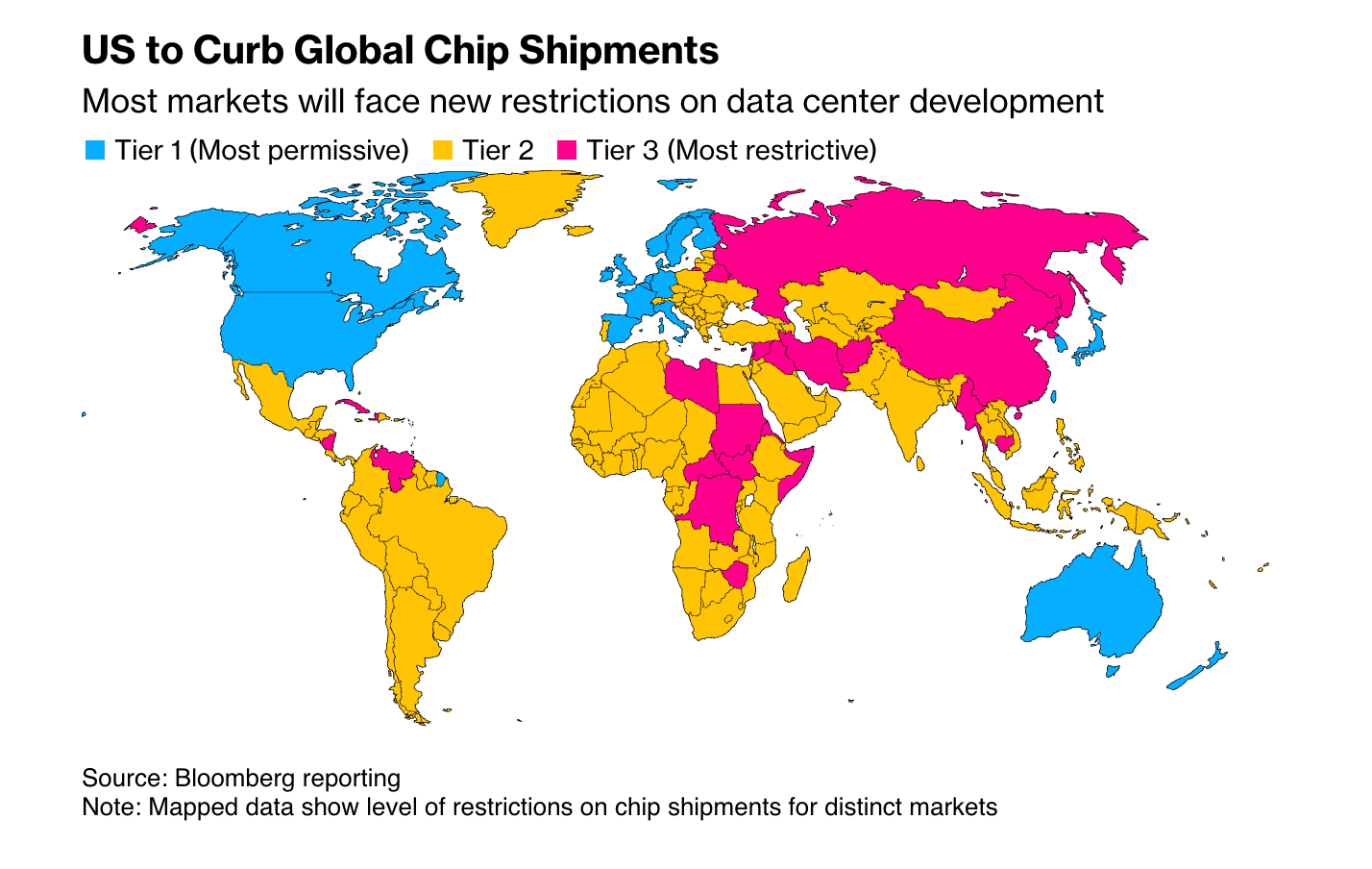

The rule’s three-tier system for categorizing importing countries

The impact of GPU smuggling and the new verification measures designed to prevent it,

How the controls will impact data center projects in the Middle East,

Whether the regulations will financially burden cloud companies and sovereign AI projects,

The political economy of export controls and what we should expect from the new Trump administration.

Listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

Mechanics of Compute Control

Jordan Schneider: To start, let’s take a step back and remind the audience why we’re doing export controls on all this AI stuff in the first place.

Jimmy Goodrich: We’re in a massive new era of the AI economy. If you haven’t been living under a rock for the last five to 10 years, the most valuable companies in the world and the most amazing new markets are being driven by AI. Where does that all sit? It sits in increasingly large, massive data centers with tens, hundreds, and possibly one day millions of semiconductor chips — the AI accelerators. The US currently is home to most of these large systems — xAI, OpenAI, Anthropic, AWS, all these companies that are training their models and inferencing them — most of that today is happening in the United States. The Biden administration is looking forward and asking how we keep that leadership here. At the same time, they’re addressing the real issue of China possibly diverting some of these chips. Is it in our national security interest to build massive sovereign AI facilities out in the middle of the plains of Kazakhstan? That’s a super meta question being answered in these rules.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on that for a second. What was the state of play beforehand, and why was the American national security establishment uncomfortable with AI data centers being diffused in the pattern they would have been had these rules not come out?

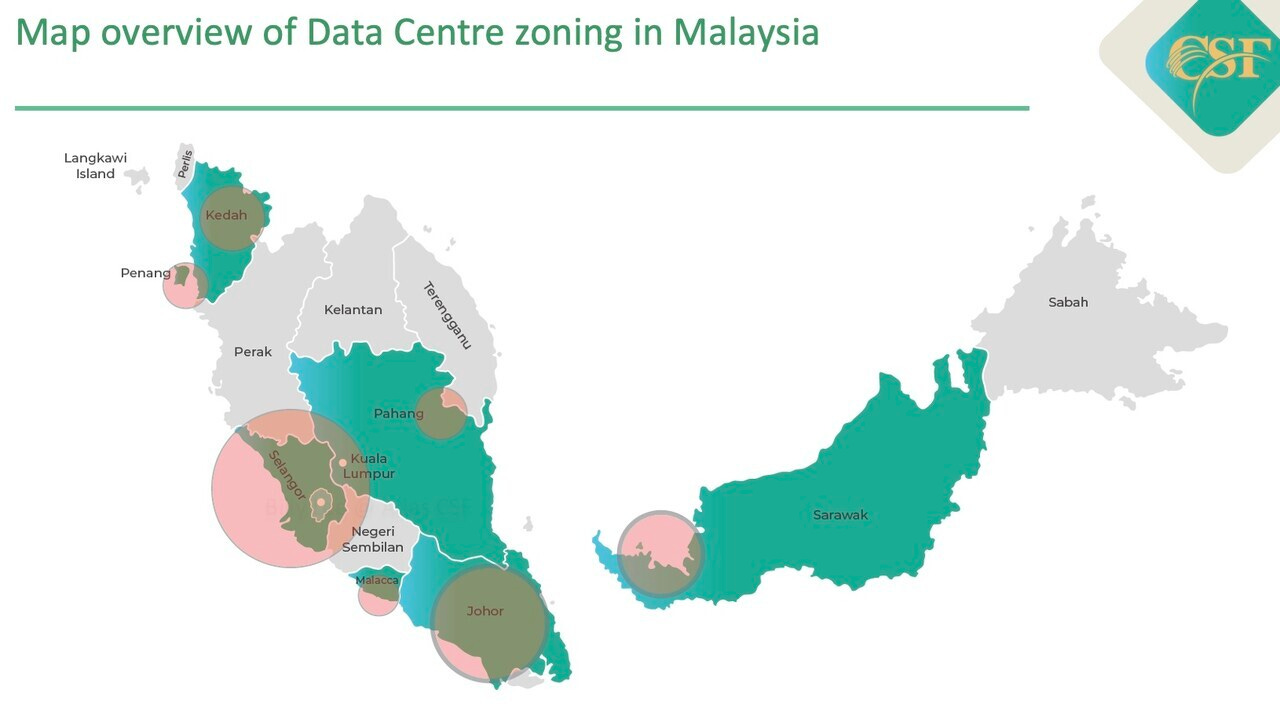

Dylan Patel: China was still able to access GPUs, whether through renting GPUs from various cloud companies — ByteDance is a top customer at Oracle, Google, and several other clouds — or through data centers being built outside of countries where the US has significant control. This includes many Middle Eastern countries and countries like Brazil, but notably Malaysia. Malaysia has been adding around three gigawatts of capacity just over the last few years. Three gigawatts of capacity is a humongous amount — Meta’s capacity at the beginning of 2024 globally for data centers was roughly three gigawatts. Malaysia as a single country is adding an entire Meta footprint in just a few years. While some of that is Microsoft and other companies like Oracle, which were probably for ByteDance and other clients, a lot of it was ByteDance directly and many other Chinese companies. It represents a significant red flag.

Jimmy Goodrich: Consider this example — YTL Power is building out data centers just across the border in Singapore. They made a big announcement with NVIDIA, but they also made a huge announcement with GDS, which is still a Chinese company. It’s literally across the street from the data center hosting this big NVIDIA cluster, and then a Chinese company is operating the data center next door with the same company. This raises many red flags.

Lennart Heim: Looking at the broader context, Jordan has covered export controls extensively. Since 2002, we’ve had export controls on PRC, China, Russia, North Korea, and arms-embargoed countries. In 2023, more countries were added to country groups D:1 and D:4, notably UAE, Saudi Arabia, and others.

Since then, we’ve seen numerous reports about smuggling and data centers being built elsewhere. Many forget that unlike missiles or other weapons, you don’t need to have a computer in your basement to use AI chips — you can dial in remotely. A company can build anywhere and access resources remotely. When facilities are built in Malaysia or elsewhere, the entities we want to prevent from accessing the underlying computing power can still access it. This rule doesn’t cover this issue.

Chris Miller: There are two ways to read this. One is that this is a major escalation in controls, creating many additional sets of rules that need to be followed. Another interpretation sees this as a natural or inevitable extension of the export controls already in place. If you’ve got restrictions on who can buy GPUs that describe certain countries as off-limits, certain countries as okay, and others as requiring a license — is there a sense in which this is a normal progression of the rules already in place?

Lennart Heim: Let’s examine how this is an escalation. Previously, we covered advanced AI chips — certain AI chips like the NVIDIA A100s and H100s — and now it additionally covers AI model weights, which we can discuss later. The expansion covers more items, but for the model weights, there are broad exemptions.

The whole world now has a classification, which wasn’t previously the case. Previously, we had basically tier-three countries, where no chips were going, and tier-two countries, where chips went under conditions or licensing. Microsoft trying to expand into the UAE is the most prominent case — G42 trying to build data centers there. Before, you needed a license for every chip you sent over. If Microsoft builds a data center there, that’s one license. If G42 tries to import the Cerebras super wafer chip, that’s another export license.

You can now read this as potentially reducing the total number of licenses needed. If Microsoft wanted to build in the UAE or elsewhere, every single shipment needed an export license. Now they can get the “universal verified end user” — one license approved, and they can deploy around the world. The designers are aware of the downsides. They don’t have enough money, there are problems with licensing. They want to take a closer look at the big shipments, the big data centers, and another look at smaller shipments where broad exemptions exist.

Data is needed on how many chips are flowing around the world. Are countries actually buying AI chips, or is it mostly Microsoft, Amazon, and other hyperscalers deploying globally? The book “Cloud Empire” discusses how these US hyperscalers are the ones building around the world. With this new system, their life is easier.

Jimmy Goodrich: This is a natural evolution. We went from the A100 level, tweaked it in 2023, added the HBM late last year. Meanwhile, the US government is trying to figure out what to do with known diversion — both virtual access to data centers by companies like ByteDance accessing huge clusters outside of China, and physical diversion. BIS is quite limited in its enforcement capability. Trying to check every data center without knowing the baseline of where all the data centers and chips are located is like finding a needle in a haystack.

The government hinted they were thinking about this in the October 2023 update when they asked industry for other ideas to address possible diversion. They mentioned on-chip controls and on-chip governance. The industry reaction was pretty lukewarm. If you’re not going to do on-chip governance and you need to address the PRC diversion issue — and ensure that dictators in the Kazakhstani deserts aren’t building AGI supercomputers without your knowledge — you need full-time visibility of where these are going. The only way to do that is through a scheme like this. Questions remain about whether this is doable and whether the Commerce Department can implement something of this magnitude.

Jordan Schneider: It’s time to hand the reins over to Lennart to tell us what’s actually in this rule. How did the Biden administration try to shape the future of AI diffusion?

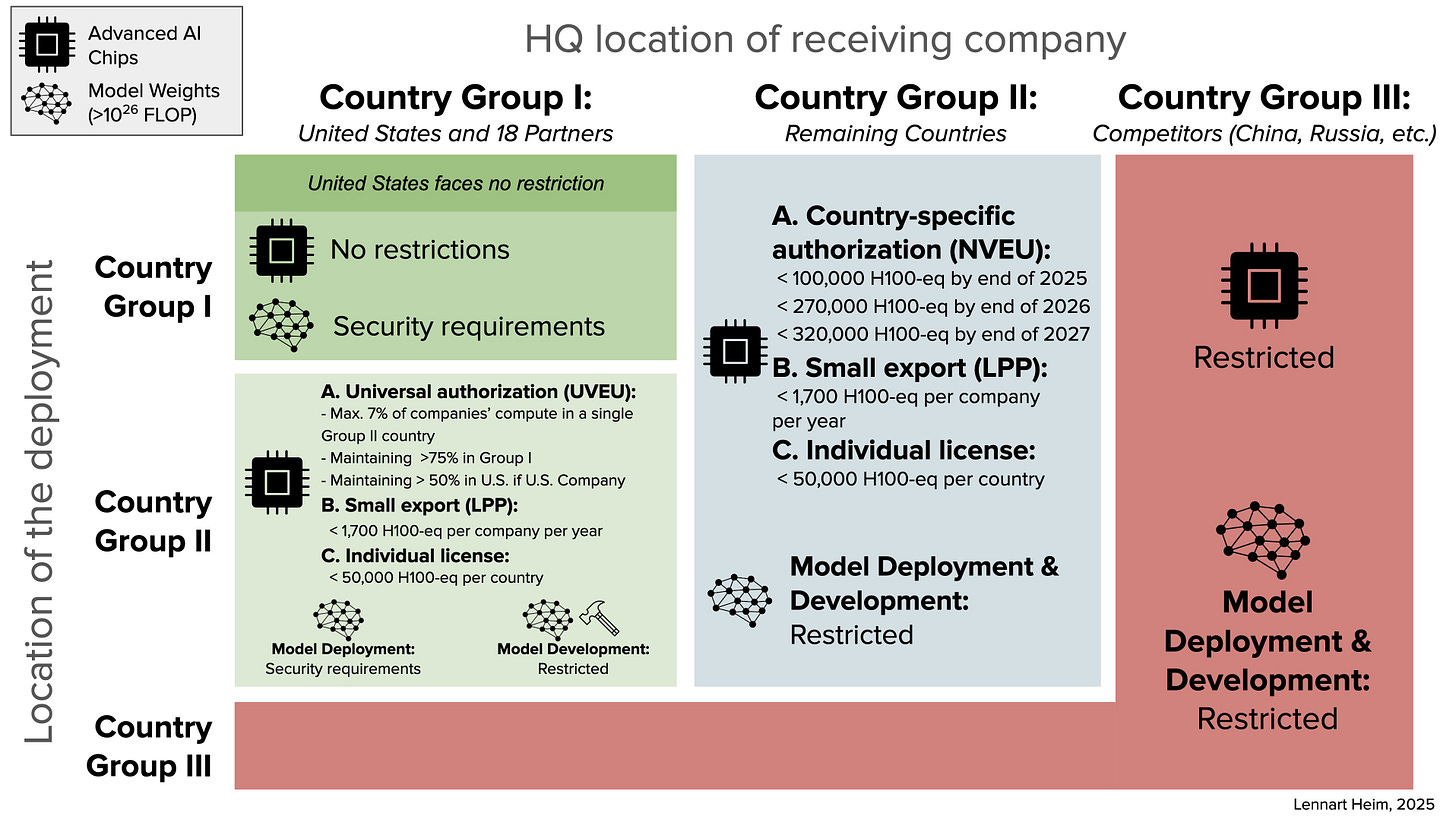

Lennart Heim: First, it’s important to understand there are three groups of countries. Previously in 2023, we had two groups. Group three consisted of PRC adversaries and arms-embargoed countries — no chips for them, which continues unchanged. Group two is now most of the world; previously this was only certain countries in the Middle East and Central Asia, like Saudi Arabia, UAE, Vietnam, and others. Group one is the US and 18 friendly nations, mostly NATO allies, Five Eyes, and Ireland.

This describes the staged approach. No chips for tier three (adversaries), tier two gets chips under conditions, and tier one has unrestricted access. We now also have export controls on model weights, defined as those using more than 10^26 floating point operations. Training such a model costs at least more than $100 million in compute, probably a billion just for hardware. Publicly available model weights are explicitly excluded. If OpenAI and DeepMind, who generally don’t release their models, were to create such models, there would be export controls on them. No model currently exists in the public domain crossing this threshold. This is about future risk — you might call it AGI — and trying to regulate future models and their deployment, with broad exemptions in place.

Chris Miller: Could we dig into tier two things? The rules for tier three exports to China are pretty clear, and tier one exports to the US, Japan, or UK are also clear. Walk us through the rules around tier two.

Lennart Heim: To make it more complicated, it always matters where we export to, but it also matters who exports — is it an American company or a non-American company? Let’s talk about American tier-one companies. When America and the 18 allied nations wanted to build in tier two — for example, Microsoft wanting to build in the UAE where they’ve had previous plans — they needed a license for each export shipment. Now they have three options.

The first option applies when staying below 1700 H100 equivalents (they measure it in computing power or total processing performance in the rule). This is roughly equivalent to 1700 Nvidia H100s, which is one of the leading chips right now. They have an exception and can basically export them with a presumption of approval. They should still notify BIS because they want to keep track of the numbers.

The second option is getting a normal license to export up to a country cap. This country cap applies to everyone who wants to export. If AWS was first, they already used some part of this country cap, which sits at roughly 50,000 H100s. That’s a lot of chips. To put it in perspective, clusters with more than 20,000 chips were limited until recently — they’re building more and more now. Elon Musk just recently announced this 100,000 H100 cluster. That represents a significant investment in chips for export.

For those who are really serious about building big things, there’s the third option, which is to undergo one of these verified end user programs. In September, BIS announced a Data Center Verified End User program (DCVU). Verified end user programs have existed for a long time in export control, giving trusted actors a streamlined way to get access.

Making it more complicated, they’ve now bifurcated this DCVU. There’s one called Universal Verified End User for companies headquartered in tier-one countries like France and the US, and there’s a National VEU for companies in tier two. The main difference is the universal one allows you to get one license, one authorization to deploy everywhere. Using the Microsoft example — they get one universal VEU and can deploy everywhere in tier two.

However, if you’re G42 in the UAE, you cannot do this. You can only get a national verified end user agreement specific to each country. Deploying in Kenya? New authorization. UAE? New authorization. Different caps apply to these different categories. Generally, the best way to deploy around the world is through universal verified end user status. This tells the tier-one companies and leading cloud providers, “Here’s your simplified way to deploy around the world.” Everyone else has a harder time deploying globally because they don’t get universal agreement, only country-specific authorizations.

Chris Miller: How do I prove to the US government that I’m verified if I want to get a VEU?

Lennart Heim: That’s exactly the key part of this diffusion rule. Before discussing export conditions, we should talk about what concerns us. We’re worried about chips being diverted to different countries through smuggling. One condition requires verifying that chips remain where they’re supposed to be. There’s a biannual chip accounting requirement where you notify BIS that all chips are accounted for. BIS even has the right to conduct on-site inspections.

There’s an interesting technical mechanism to verify chip location through pinging. If you have a computer somewhere and ping different computers worldwide, knowing how long it takes for this ping to travel allows you to geolocate it. This shows BIS telling hyperscalers and hardware companies, “You built this beautiful AI tech — can you build technical mechanisms to help with our problems?” Making sure chips stay put is the first priority.

Another concern involves data centers. Sometimes you want to serve local government and business needs, but more prominently, you want to help leading AI companies deploy globally. ChatGPT needs local deployment to minimize latency and fulfill data requirements — that’s a common motivation for hyperscalers to expand worldwide. When you deploy model weights on a cluster in Saudi Arabia, many people worry about securing this knowledge, as model weights are the most valuable element.

To become a verified end user, you must meet cybersecurity requirements and physical security requirements to keep the processing and model weights secure. Stealing model weights is similar to stealing GPUs — if someone has stolen the model weights that required significant compute power, they don’t need the GPUs anymore. The focus is preventing smuggling, keeping assets in place, and most notably, securing model weights. These explicit security requirements for protecting model weights are unprecedented.

Jimmy Goodrich: Lennart, it’s worth mentioning that we’re only talking about the restricted category 3A090 chips, essentially Nvidia A100 level and above. Looking at older medium-tier Intel Xeons, AMD processors, lower-performance GPUs, V100s — those don’t count. It’s basically A100 level and above.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on that for a second because the Nvidia press release we’re going to discuss today mentioned that gaming chips would be controlled by that.

Lennart Heim: There’s an A/B categorization that’s important to understand. Tier two only has controls on category A — that’s only data center chips. Any gamer in Saudi Arabia, UAE, India is fine.

Jimmy Goodrich: It doesn’t apply to autonomous driving chips either. Your Jetsons are excluded from that as well.

Lennart Heim: Indeed. In the PRC, there is a notification requirement if your gaming chip is above a certain threshold of processing performance. Nvidia needs to notify BIS about these kinds of exports so they have visibility into these activities.

When we talk about data centers being built, we’re talking about AI. When I mention share of computing power, it means AI computing power. These data centers use GPUs with chips costing about $30,000 each. This isn’t about data centers used for watching Netflix or using anything in a Microsoft suite or cloud. This is about data center GPUs being used for AI workloads. All other operations can continue as usual.

Jimmy Goodrich: A good way to think about it is you’ve got your standard data center for web storage, but we’re talking about accelerated AI compute, which is an entirely different category. You have much more liquid cooling, more cooling fans and towers. You literally engineer the data center differently to accommodate these AI-accelerated computing clusters. You can see it visibly when driving around places like Loudoun County — this data center doesn’t have the 50 cooling fans surrounding it or the massive compressed liquid cooling tanks. There’s a categorical difference between AI data centers and your traditional web storage or cold storage data center.

Chris Miller: How does this play out over time? Right now we’ve got the level of chips that are restricted, but chips get better at a pretty rapid rate. Should we expect regular updates so that as chips age out they get opened up, or will this largely remain frozen with real restrictions imposed on what types of data centers can be built in third countries?

Lennart Heim: Setting aside the policy question of whether to move it up or not, let’s look at the reality. Computing chips are improving exponentially. More chips will run into these restrictions. More importantly, we claim it’s only AI data center chips, but more chips are becoming AI chips. More workloads are becoming AI applications. Everyone has seen it — whatever software you open nowadays has a new AI feature.

This highlights a key challenge. More chips are becoming AI chips, therefore they have increased performance. They might eventually hit these thresholds. For example, at some point an Apple Ultra chip might hit these thresholds. Then you must ask the US Government whether we should control these chips and how useful they are for the things we’re worried about.

It gets more complicated. Can you hook up a bunch of Minis and build a supercluster? It’s clearly not as good as the alternative, but practically speaking, computing power is computing power. When you have something exponentially improving and draw a line in the sand, it will eventually get crossed. This needs continuous improvements and threat model assessment. Maybe it turns out fine for AI in the next three years — then clearly this line should go up. But if developments accelerate next year, there might be reasons to control these things. Export control is a blunt tool. You will hit more targets, and the more things become AI-related, the more things you will affect. That’s a fundamental challenge of this framework.

Chris Miller: Dylan, what do you think about the financial implications for the companies? One of the debates has been whether this is impactful to companies or if they will sell the same number of GPUs, just put them in different countries. Dylan might have a view on that.

Dylan Patel: This regulation definitely impacts the financials of many companies in the space, primarily NVIDIA. You can argue the GPUs will just get rerouted, but that’s not always the case. A significant number of GPUs would not have data center capacity in the West — there is a data center shortage. This explains why people are converting anything they can into a data center. That opportunity is now gone. You can’t reshore everything. China was increasing demand for GPUs and affecting the elasticity of demand required for supply creation and sales to them. NVIDIA is impacted — it isn’t just wholesale rerouted because of data center capacity and potential demand issues. On the flip side, companies that can get a universally verified list will benefit massively.

Jimmy Goodrich: Companies will find a way to get these licenses for the real demand out there for huge AI data centers, particularly the universal VUs and large hyperscalers. They have the resources, huge teams, lawyers — they’re all FedRAMP certified, as the rules require. It will be much easier for them.

The big question concerns the NVEUs — these sovereign AI cloud startups or small GPU-accelerated cloud projects in different parts of the world. Will they have the wherewithal to do this? Well-resourced organizations like G42 will absolutely take a shot. But will the Nepalese cloud supplier thinking about this actually make it through? If they don’t, should they have been building an AI data center in the first place?

These questions might force a rethink among some sovereign players who were considering spending $5-10 billion of their government money on data centers instead of healthcare, education, or transportation for their citizens. What is the actual viability of these sovereign AI projects in different parts of the world? Some are totally legitimate with real demand. Others are somewhat questionable.

Sovereign AI: Vanity Project or Natsec Necessity?

Good AI is good and bad AI is bad, but how do lawmakers tell the difference? Will AI bring the world together or balkanize the internet beyond repair? Why do governments even need cloud computing anyway?

One key indicator to watch is what companies are saying to their shareholders. Watch carefully to see if any affected companies put out statements notifying shareholders of possible negative impacts. We haven’t seen anything yet, which doesn’t mean we won’t. It’s a huge regulation that will take time to work through and understand exactly how to revise financial projections. Previously, we’ve seen companies claim something would be catastrophic to their business, have a massive negative effect, and then clarify to shareholders that it wouldn’t have any effect at all.

Lennart Heim: Anyone who’s worked in export business is used to this. What’s different this time is that it’s public, being done via press statements. The Oracle press statement is definitely worth reading to get an idea of the mood out there. As Jimmy was saying, the question is whether they’re complaining because of real financial impacts, or because the administration is changing and now they can protest at full throttle without constraints. To some degree, it makes sense to take a shot at potentially killing it in the next administration. It’s hard to balance these considerations — is there a real impact we should discuss, or is this just taking advantage of an opportunity? We haven’t seen such public backlash against export controls before.

Jimmy Goodrich: It impacts every company differently depending on their market position. Companies designing and selling controlled GPUs are most impacted. Companies integrating them into hardware and selling them as part of a solution, like Oracle, are basically as impacted as the chip makers. It might actually be more favorable for the tier one hyperscalers because you get one license to operate around the world. For sovereign NVEU operators in tier two countries, many won’t make it through NVEU authorization, but many will. It will be interesting to see where the dust settles.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting to consider the political economy of Google, Amazon, and Microsoft not supporting this, even though it’s a regulatory burden that could eliminate many competitors. Brunei, if they want cloud services, will have to go to AWS rather than build sovereign AI brought by Nvidia DGX cloud.

Jimmy Goodrich: Looking at business history, when has any industry welcomed a new regulatory framework that oversees most of their business? It’s natural for them to prefer selling to whomever they choose at their own pace. The Biden administration is saying they need oversight to check customers and ensure they meet security standards preventing Chinese access.

Consider historical parallels like the debate over seatbelts in cars — car companies initially opposed that idea. Or the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, where industry claimed they couldn’t operate with restrictions because they needed to make payments to extract oil in places like Zimbabwe. The law passed, people complied, and moved on. It’s natural for businesses to resist new regulatory oversight of their business model. This shouldn’t surprise anyone. The real impact will become clear when we examine the financial statements over time.

Chris Miller: One other question on that front — Dylan mentioned the build-out happening in Malaysia as a good example. There have been discussions that some is for Malaysian domestic demand, while some might be diverted towards China, maybe a lot of it. Jimmy, what’s your view on the share of GPUs currently going to tier two countries? What portion is for tier two country demand versus likely diversion? Is it 20% diversion, 80% diversion? Hard to know exactly, I’m sure.

Jimmy Goodrich: No one really knows because those numbers are only visible to the suppliers of chips and server-level systems integrators. In 2023 and 2024, we saw some interesting spikes in sales to Southeast Asia. As Dylan pointed out, there’s real data center growth happening there. Indonesia is building data centers, with many Chinese companies building locally. With China’s slowing economy, some listed Chinese data center companies like GDS and 21Vianet are growing faster outside China than inside.

The Wall Street Journal and The Information have reported that ByteDance, although technically headquartered in Singapore, has been looking at accessing these data centers in Malaysia. In some cases, you’ve got a big AI-accelerated data center right next door to a GDS data center owned by the same company. Huawei and others have had large manufacturing operations in Malaysia, with reports of diversion occurring there.

Regarding real end use, we don’t really know. Reports indicate that Nvidia physically inspected data centers to verify chip installation, but they only looked once. After inspection, everything was shipped out — the entire data center was built as a scam for inspection. They packed it all up and moved it out, like a Looney Tunes animation secretly swiping everything out the back door. These new rules are saying more oversight is needed. What was in place before, mostly industry self-initiating, despite good efforts, isn’t enough.

Lennart Heim: None of this surprises anyone who has followed the semiconductor industry and export controls — there are wider schemes to accomplish goals. The advantage of computing power is you want to move the unit of governance from AI chips, which are hard to govern and can be smuggled, to computing power itself. Who’s using the computing power? You move in this domain by saying that even when selling to a trusted entity, we need this continuous, ongoing relationship with you as a verified end user. Then you check that your customers aren’t diverting computing power. We could have all the chips outside the PRC, but they could still use them. You want to ensure whoever operates this is checked for their usage, which is exactly what cloud businesses do. Practically speaking, it provides better governance.

Jimmy Goodrich: Another important element ensures the US doesn’t look away as data center capacity is built overseas, particularly by deep-pocketed sovereign nations. We’ve seen this with semiconductors through the early 2000s. Chris, you wrote about this in Chip War — Taiwan, South Korea, China, Singapore doling out billions in cash incentives for semiconductor factories. The US share of semiconductor manufacturing dropped from nearly 40% in 1990 to less than 20% , requiring billions to recover.

This appears to be a preemptive measure to keep advanced data center capacity in the United States. Countries like Saudi Arabia and UAE have over a trillion dollars in cash, eyeing these companies and data centers. The fear is waking up in 10 years wondering how our AI ended up in a desert, controlled by nations friendly with Russia and China. We should have had policy earlier to prevent that. Lennart, you should probably discuss the ratio thing, which is crucial for tier one because it addresses that issue.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on that for one second, Jimmy. It’s illustrative that the Biden administration paired this with an executive order trying to create easier ways to get carveouts for building new power plants. Trump also seems influenced on this — his influencer’s initials might be E and M, but you never know. Power generation is the big bottleneck domestically in building out more data center capacity.

It’s a two-step game — if you don’t want the infrastructure built abroad, you need to make sure it’s possible to build in all those tier-one countries. A domestic regulatory agenda needs to be paired with all this. During World War Three, these buildings would be a weird asset — protecting them is another issue we’ll address when necessary.

Lennart, this reminds me of the Washington Convention of 1923 — the US gets five ships, the UK gets five ships, Japan gets three ships, Germany gets one and a half ships. Now we’re doing this for AI compute. What’s the ratio deal within this regulation?

Lennart Heim: The word “ratios” could be better chosen. It could be called “share.” Jimmy was alluding to how 20% of semiconductors are produced in the US — that’s not great and should be different. This framework requires that if you’re a universal verified end user who can deploy around the world, like Microsoft, 75% of all your AI computing power must be built in tier one. US companies must keep 50% of their whole share in the US.

That means Microsoft must keep half of its computing power in the US. The recent AI executive order on permitting infrastructure, building data centers, and getting more energy is critical. If you tell companies to build here, you must simplify the process. We’ve had issues getting transmission lines and everything else ready in the US for the data center buildout needed in the future.

Companies must keep 50% in the US, 75% in tier one, leaving 25% for the rest of the world. This is per company, not the total share of all chips worldwide. You can have 25% in tier two because nothing can go to tier three. Within tier two, you’re only allowed to put 7% in a single country. If Microsoft wants to build a big cluster in Saudi Arabia, the cluster can only be 7% of their whole computing power.

The numbers emphasize America first — America and our partners first. The data centers must be kept here for security. The role of AI in World War Three and the longevity of these data centers remains uncertain, but currently, keeping them here ensures security.

Jimmy Goodrich: This is definitely forward-leaning because the United States rarely considers how to stay ahead with allies at the cusp of an industrial revolution. Many other industries, particularly physical assets, have dispersed around the world. Look at the procession of “kiss the ring” voyages over the last two years — when Saudi Arabia or UAE hold a tech conference, every tech leader rushes there praising sovereign AI. This isn’t because they have a huge population of internet users wanting ChatGPT access or because of strategic location — it’s because they have enormous cash reserves.

If you’re a big tech company offered substantial money, you’ll build there regardless. The US Government is now saying that while cash is good for companies, national security implications must be considered. The fastest supercomputer in the United States modeling nuclear weapons, just installed at Lawrence Livermore National Lab, has 44,000 GPUs. This rule allows any country to build a supercomputer of that size. Every tier-two country remains tactically able to build really powerful supercomputers — some of the most powerful in the United States aren’t even that large.

Lennart Heim: The numbers are critical here, as is the status quo. The rule includes total processing performance numbers — they’re big numbers nobody will grasp. We mostly discuss H100 equivalents. When setting these ratios requiring 75% in tier one, the US government surely crunched these numbers knowing more than 75% is currently in tier one and more than 50% is in the US — probably significantly more.

Looking at the current reality of AI compute worldwide, it’s quite concentrated with the big hyperscalers, primarily in the US, then in other tier-one nations, followed by tier-two nations. The goal is maintaining this structure because, as Jimmy mentioned, some entities have deep pockets. The message is, these pockets are deep, but they aren’t bottomless.

Jordan Schneider: Keeping the data centers here reveals a central contradiction in Biden’s initial approach. The Biden line toward China was always “small yard, high fence” — they weren’t trying to contain China’s economic rise, but viewed this as a national security question. They weren’t comfortable with China having technology to model missiles. These regulations only matter if AI becomes more important, not just in a national security context, but in economic growth.

You’re using these to constrain technology that impacts both military outcomes and has potential for industrial revolution-level effects on a nation’s economic prospects. Two questions arise here.

To what extent will having data centers in the US and allied countries privilege those nations in gaining economic benefits from AI? If you’re in a country with lag time or you’re stuck going through AWS or Microsoft, are you losing out on vertical integration benefits from artificial intelligence?

Will the Trump administration stick to this line? It doesn’t fully align with logic, since you’re clearly constraining other countries’ future economic potential by limiting AI access. Once Trump talks about being in an AI race and intending to win it, that creates second-order effects. This doesn’t align with “small yard, high fence” — sitting down with Wang Yi for 12 hours explaining these export controls are just for this small thing that only affects missile systems.

Chris Miller: Jordan, isn’t the fact that API access remains broadly open the counterargument?

Jordan Schneider: Maybe it doesn’t even matter. It’s just an off switch for the future, unless there’s some significant lag where using compute in a tier-one country from far away will slow you down.

Lennart Heim: Latency might be an issue, though not for current frontier models where computational workload is high. You constrain people from accessing GPUs directly, where they’d have more flexibility, versus only getting computing power as infrastructure-as-a-service. Leading AI developers don’t keep GPUs in their rooms or basements — they dial in remotely via cloud computing.

Most people access it through the cloud, with all its benefits and downsides. AI is a dual-use technology — more chips are becoming AI chips. Export controls are blunt instruments. It’s extremely difficult to carve out one specific concern. If you’re worried about AGI, by definition it’s general — you can try to take over the world or grow your economy. You can still access computing power unless you want to train a really big model. Similar to the banking system, it gives on-demand access with the possibility of cutting off access — this is weaponized interdependence.

Jimmy Goodrich: This data center revolution will drive massive upstream infrastructure growth — energy, water, concrete, steel — creating new industries in the United States. That’s a huge net positive for the US and its allies. However, research shows you benefit most from diffusing AI throughout your economy. If you’re Thailand, you’ll get more value from $5 billion spent incentivizing AI use versus developing sovereign AI.

Quickly integrating AWS, OpenAI, or Meta into banking, utilities, public transportation, and healthcare will determine which economies succeed — you don’t need locally hosted AI. The challenge comes with sensitive personal data that countries want to keep within their borders. Solutions will emerge through NVEU or UVEU systems. These rules don’t prevent building in tier-two countries — they just require additional steps.

Will Adversaries Fill the Void?

Jordan Schneider: Okay, Jimmy. Let’s talk about China.

Jimmy Goodrich: The mega question is whether China can fill the void. No one wants to see China fill a void anywhere. China having the digital Silk Road in Africa and the Middle East poses a major challenge for the United States. Travel the world and you’ll see Huawei or ZTE phones in citizens’ pockets throughout the developing world, or Huawei cloud offering email web services, or Chinese companies offering Smart City and surveillance solutions.

However, that’s entirely different from AI-accelerated solutions. Due to the technology’s complexity — producing sub-7 nanometer semiconductors for advanced AI accelerators, 3D stacking layers of the most advanced DRAM for HBM — plus all the export controls, China is struggling to meet its own demand with indigenous AI GPU production. Reports indicate China’s operating one, maybe two factories to produce advanced logic chips around 7 nanometer, which is two or three generations behind where TSMC, Samsung, and eventually Intel will be. On HBM, China is just starting up several efforts and remains years behind.

The big question is, can China swoop into the UAE, Brazil, and India with a ready-to-go, full-stack ecosystem? Today, the answer is no. Even in delivering to Baidu and Tencent within China, they’re struggling to meet fulfillment orders. Numerous reports highlight how lower yields and production issues at SMIC and other facilities create challenges for China.

They will improve — anyone who’s written off China from an innovation perspective usually gets it wrong. However, this isn’t just about innovation — it’s about scale. China will eventually produce five, maybe even four-nanometer chips, but they need to produce millions of units. They need millions of HBM units, millions of packaging substrates for integration, plus excellent software for easy plug-and-play with customers worldwide.

Even if China could export large quantities of their AI chips, would a sovereign AI company in Thailand have the skill set to completely re-engineer its software stack to run on something like the Huawei Mindspore? Probably not. That skill likely only exists in the United States and China.

What’s likely to happen is developing economies unwilling to navigate licensing hoops will buy H20s — good chips usable for inference. Many sovereign AI projects focus on inference, not training, because they can rent that capability to other companies and players.

I’m skeptical of claims that China will capture market share from US players. Currently, China can’t meet its own demand. This could change — we must watch closely. That’s why all roads lead back to export controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment and leading-edge semiconductor fabrication. If those don’t work, none of this policy works. It’s like a house of cards.

Jordan Schneider: Lennart, Jimmy mentioned inference. The last show we did about a month ago discussed the increasing importance of inference versus training when producing and getting the most out of models. How does that technological development interact with this rule, which was years in the making, probably before scaling on inference-time computing became widely recognized?

Lennart Heim: This rule leverages existing export control by using the same export control number. The H20 is not being controlled — everyone around the world can buy an H20 as much as they want. This is good for Nvidia’s revenue stream, particularly in China. The line between training and deploying becomes more blurry over time. When you deploy for longer and let the model think for longer, it leads to better capabilities.

For careful readers of this rule, there’s a reporting requirement if your chip has a higher memory bandwidth than a certain amount, which the H20 meets. My understanding is that if you export it, you need to give BIS a heads-up. They want some idea of how many H20s are out there, which seems sensible. If not many people are buying it, it might be fine, but if many people are buying it, intervention might be necessary. These export interventions need to expand to cover the H20 for more exhaustive coverage of new AI developments.

Jimmy Goodrich: This point is super important because if you read carefully the criticism from the private sector, it claims this will tie the hands of American companies while China comes through. The reality is that today, no one has been able to find a single data center outside of China that’s at scale — meaning 10-20,000 H100 equivalent — fully loaded with semiconductors built indigenously within the PRC. Those don’t exist today.

There’s a huge barrier that a local sovereign player would have to overcome to port their whole system from CUDA software to Huawei MindSpore. This is actually a major, underappreciated advantage that U.S. companies have — everyone’s already coding and developing AI frameworks on the existing firmware that these companies, AMD included, have developed. That itself is a huge disincentive to use Chinese systems.

China could play it smart by telling their Chinese companies to use a larger quantity of H20s, then start exporting a smaller quantity to some keystone projects to claim the US AI diffusion rule isn’t working. It’ll be important to look at the overall numbers to see the actual scale. If China can produce millions of comparable GPUs loaded with comparable HBM, we would need to take a hard look at this rule and the levels being set. However, the evidence shows that China isn’t there yet.

Lennart Heim: The most likely way this could fail is by assuming that because it’s fine now, it will be fine in the future. That’s far from granted. It needs to be monitored, and we need to examine the evidence and data. As Jimmy was saying, we tried to find data centers and didn’t find any. I found only two systems trained with Ascend 910s out of approximately 700 systems in the database, with hardware information for 260. People aren’t really using it. If this changes — and this is a job for the intelligence community and others — it needs to be monitored and adapted. This is the most likely way things can go wrong if we’re too stringent and they just fill the void.

Jordan Schneider: One last point about what you don’t get from having your own data center. Kevin Xu wrote a fantastic article about DeepSeek’s three advantages. One thing he pointed to as part of their special sauce is that because they came from a quant hedge fund, they’ve been running their own servers for 15 years. One of his theories about how they were able to be so efficient with their training is their expertise all the way up and down the stack when it comes to training models.

There could be a future where having to outsource much of what you do to Google or AWS means missing out on technological innovations. Companies in other countries around the world might not be able to explore different ways of training and deploying models. These are the trade-offs we’re weighing when considering all the different risks here.

Lennart Heim: It would be wrong to tell ourselves we can have the best of both worlds simultaneously at no cost. This clearly isn’t the case when you intervene. The rule reflects where people fall regarding national security risk and how much should be done here. That’s what we got.