Why is Trump appeasing Russia? What lessons can we learn from the battlefield in Ukraine? How will AI change warfare, and what does America need to do to adapt?

To discuss, we interviewed Shashank Joshi, defense editor at the Economist on a generational run with his Ukraine coverage, and Mike Horowitz, professor at Penn who served as Biden’s US Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for force development and emerging capabilities in the Pentagon.

We discuss….

Trump’s pivot to Putin and Ukraine’s chances on the battlefield,

The drone revolution, including how Ukraine has achieved an 80%+ hit rate with low-cost precision systems,

How AI could transform warfare, and whether adversaries would preemptively strike if the US was on the verge of unlocking AGI,

Why Western military bureaucracies are struggling to adapt to innovations in warfare, and what can be done to make the Pentagon dynamic again.

This episode was recorded on Feb. 26, two days before the White House press conference with Zelenskyy, Trump, and JD Vance. Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app.

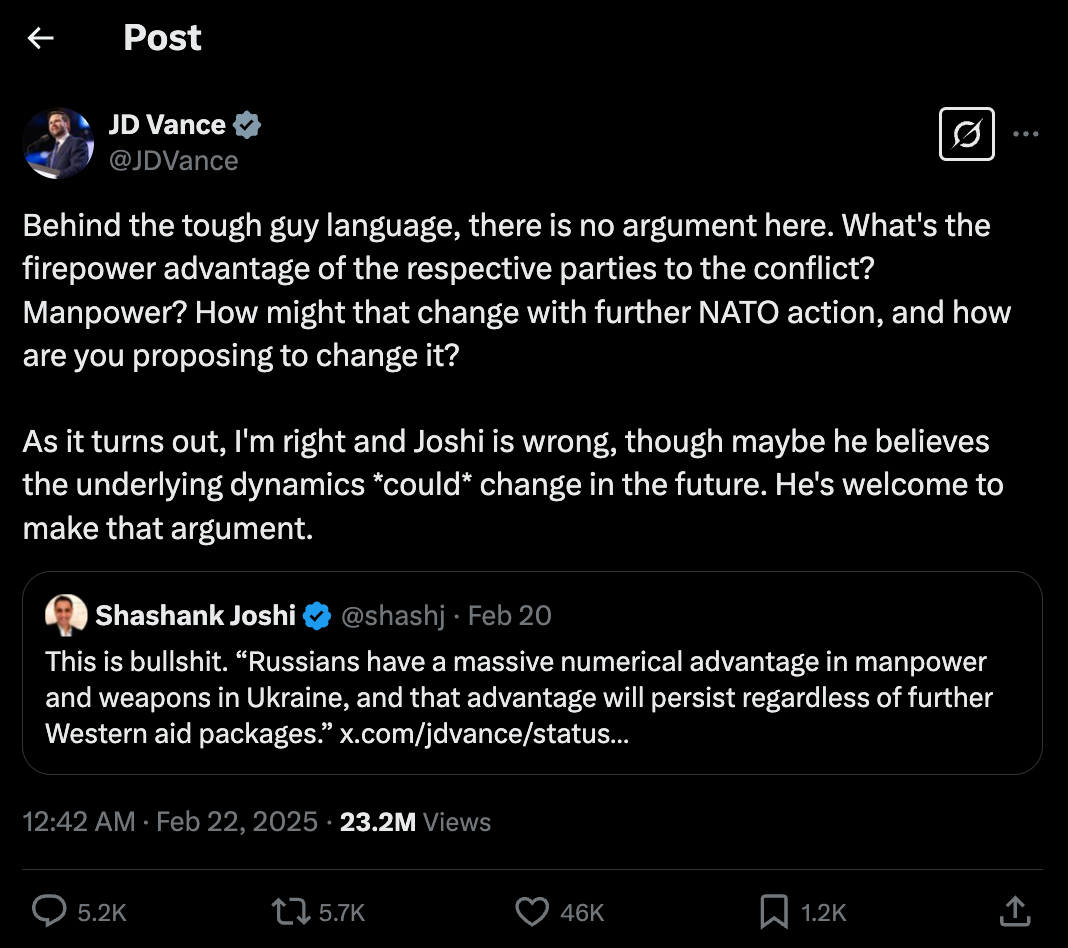

Jordan Schneider: Shashank, it seems you had a lot of fun on Twitter this week?

Shashank Joshi: I was in a swimming pool with my children on holiday in the middle of England and didn’t notice until 18 hours after the fact that the Vice President of the United States had been rage-tweeting at me over my intemperate tweets on the subject of Ukraine. I provoked him into this in much the same way that he believes Ukraine provoked the invasion by Russia.

Jordan Schneider: What does it mean?

Shashank Joshi: It means the Vice President has far too much time on his hands, Jordan.

This is a pretty significant debate. Fundamentally, this was about whether Ukraine is fated to lose. His contention is that Russian advantages in men and weapons or firepower meant that Ukraine’s going to lose no matter what assistance the United States provides.

My argument was that while Ukraine is not doing well — I’m not going to sugarcoat that, I’ve written about this and it’s made me pretty unpopular among many Ukrainians — it’s not true that advantages in manpower and firepower always and everywhere result in decisive wins. Indeed, Russia’s advantage in firepower is much narrower than it was. The artillery advantage has closed. Ukraine’s use of strike drones — which we’ll talk about later — has done fantastic things for their position at the tactical level.

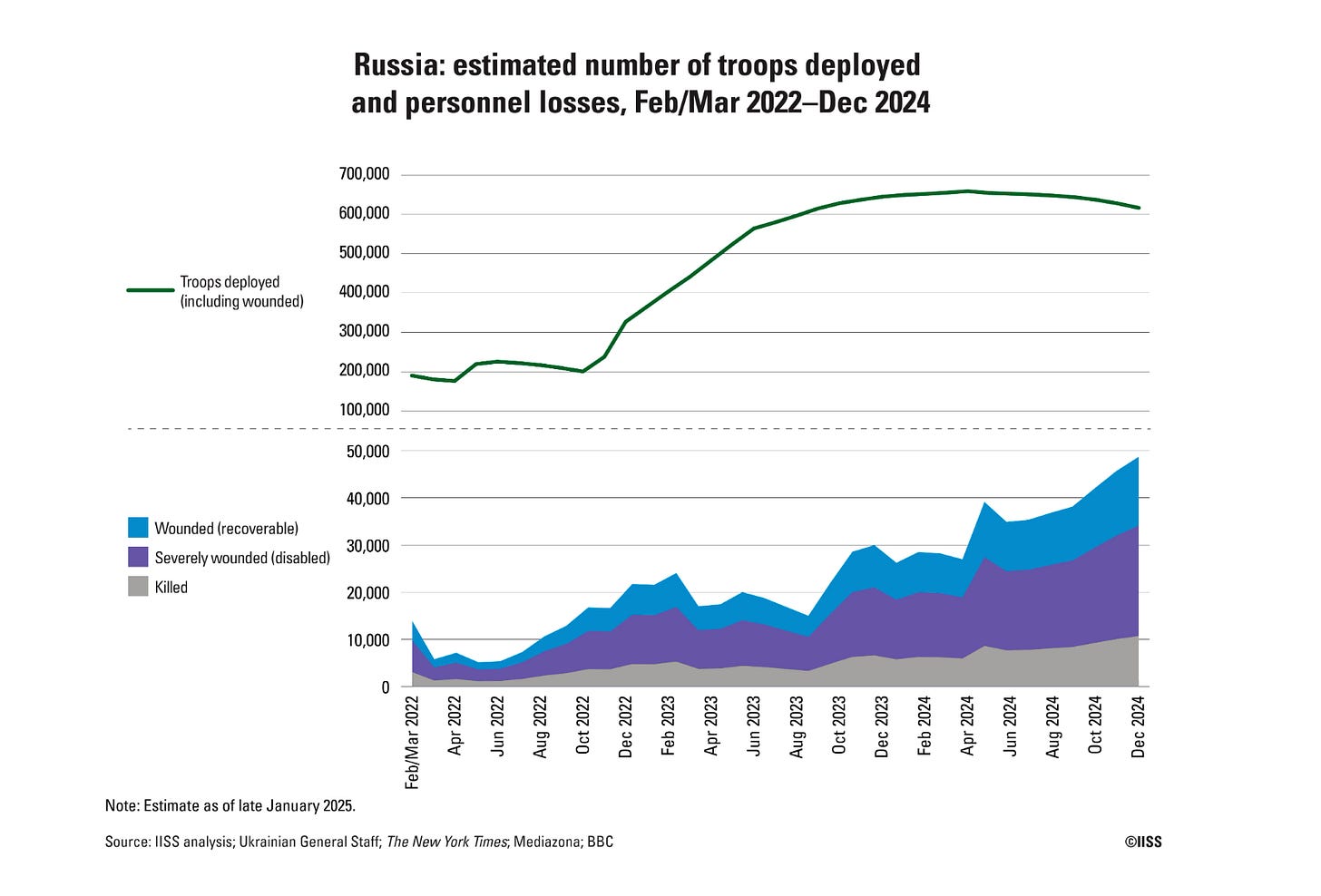

On the manpower side, Russia is still losing somewhere in the region of 1,200-1,300 men killed and wounded every single day. While it can replenish those losses, it can’t do that indefinitely. I’m not saying Vance is completely wrong — I’m just saying he is exaggerating the case that Ukraine has already lost and that nothing can change this.

My great worry is this is driving the Trump administration into a dangerous, lopsided, inadequate deal that is going to be disastrous for Ukraine and disastrous for Europe. I’m worried profoundly about that at this stage.

Michael Horowitz: Quantity generally sets the odds when we think about what the winners and losers are likely to be in a war. Russia has more and will probably always have more. But there are lots of examples in history of smaller armies, especially smaller armies that are better trained or have different concepts of operation or different planning, emerging victorious. Most famously in the 20th century, perhaps Israel’s victory in 1967.

Jordan Schneider: We have three years of data. It’s not like you’re playing this exercise in 2021. You’re doing this exercise in February of 2025. By the way, Mr. Vice President, your government actually has a ton of the cards here to change those odds and change the correlation of forces on the ground, which just makes the argument that this is a tautology so absurd coming from one of the people who is in a position to influence and who has already voted for bills that did influence this conflict.

Shashank Joshi: Wars are also non-linear. You can imagine a war of attrition in which pressures are building up on both sides, but it isn’t simply some mathematical calculation that the side with the greatest attrition fails. It depends on their political cohesion, their underlying economic strength, their defense industrial base, and their social compact.

The argument has been that although Russia feels it has the upper hand — it has been advancing in late 2024 at a pace that is higher than at almost any time since 2022 — there’s no denying that to keep that up, it would have to continue mobilizing men by paying them ever higher salaries and eventually moving to general mobilization in ways that would be politically extremely unpalatable for Vladimir Putin. War is not just a linear process. It’s a really complicated thing that waxes and wanes, and you have to think about it in terms of net assessment.

Michael Horowitz: That’s especially true in protracted wars. I’m teaching about World War I right now to undergraduates at Penn. One of the really striking things about World War I is if you look at the French experience, the German experience, and the Russian experience in particular, given the way that World War I is one of the triggers for the Russian Revolution, how their experience plays out in World War I is in some ways a function of political economy — not just what’s going on on the battlefield, but their economies and the relationship to domestic politics and how it then impacts their ability to stay in and fight.

Jordan Schneider: America has levers on both sides of the political economy of this war. There was a point a few weeks ago when Trump said he was going to tighten the screws on Putin and his economy. The fact that we are throwing up our hands and voting with Putin in the United Nations, saying that they were the aggressor, just retconning this entire past few years is really mind boggling. There was a line in a recent Russia Contingency podcast with Michael Kofman, where he says “The morale in Munich was actually lower than the morale I saw on the front in Ukraine,” which is a sort of absurd concept to grapple with.

Michael Horowitz: If you were to mount a defense here, what I suspect some Trump folks might say is that they believe this strategy will give them more leverage over Russia to cut a better deal. That involves saying things that are very distasteful to the Ukrainians, but they think as a negotiating strategy, that’s more likely to get to a better outcome.

Shashank Joshi: That’s right, Mike. Although they’ve amply shown they are willing to tighten the screws on Zelenskyy. If you were looking at this from the perspective of the Kremlin, would you believe General Keith Kellogg when he says, “If you don’t do a deal, we’re going to ram you with sanctions, batter you with economic weapons"? Or do you listen to Trump’s rhetoric on how we’re going to have a big, beautiful economic relationship with Russia and we’re going to rebuild economic ties, lift sanctions?

You’re going to be led into the belief that the Americans are really unwilling to walk away from the table because the Vice President and others are publicly saying we don’t have any cards, that the Ukrainians are losing, and if we don’t cut a deal now, then Russia has the upper hand. It puts them in a position of desperation.

My big concern is not just that we get a bad deal for Ukraine, it’s that the idea of spheres of influence appeals to Trump, dealing with great men one-on-one, people like Kim Jong Un, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping — and that what will be on the table is not just Ukraine, but Europe. Putin will say, “Look, Mr. President, you get your Nobel Peace Prize, we get a ceasefire, we do business together and lift sanctions. And you can make money in Moscow, by the way. Just one tiny little thing, that NATO thing. You don’t like it, I don’t like it. Just roll it back to where it was in 1997, west of Poland. That would be great. You’ll save a ton of money here. I’ve prepared a spreadsheet for you.”

That is the scenario that worries us — a Yalta as much as a Munich.

Jordan Schneider: We have a show coming out with Sergey Radchenko where we dove pretty deep into Churchill’s back-of-a-cocktail-napkin split. At least Churchill was ashamed.

It’s so wild thinking about the historical echoes here. I was trying to come up with comparisons, but the only ones I could do were hypotheticals. Like McClellan winning in 1864, or — I mean, Wendell Willkie was actually an interventionist. There was some Labor candidate that the Nazis were trying to support in the Democratic Party in 1940, but he never made it past first base. Has there ever been a leadership change that shifted a great power conflict this dramatically?

Shashank Joshi: From the Russian perspective, that’s Gorbachev. Putin would look back at glasnost, perestroika, and Gorbachev at the Reykjavik summit as moments where a reformist Soviet leader sold the house to the Americans and threw in the towel.

Michael Horowitz: You also see lots of wars end with leader change, with leadership transitions, when wars are going poorly for countries and you have leaders that are all in and have gambled for resurrection. If you think about the research of someone like Hein Goemans back in the day, then you have to have a leadership transition in some ways to end wars in some cases if leaders are sort of all in on fighting.

Jordan Schneider: The Gorbachev-Trump comparison is a really apt one because it really is like a true conceptual shift in the understanding of your country’s domestic organization as well as role in the world. Gorbachev, for all his faults, at least had this universalist vision of peace, trying to integrate in Europe — he wanted to join NATO at one point. But going from that to whatever this 19th century mercantilism vision is, is really wild to contemplate.

Shashank Joshi: The other thing to remember is Gorbachev’s reforms eventually undid the Soviet empire. They undid its alliances and shattered them. In the American case, the American alliance system is not like the Soviet empire. France and the UK are not the Warsaw Pact. We bring something considerably more to the table. It’s a voluntary alliance. It’s a technological, cultural alliance. These are different things.

I worry sometimes that this administration or some people within it — certainly not everybody — views allies just as blood-sucking burdens. What they don’t fully grasp is how much America has to lose here. I want to say a word on this because Munich — and I heard this again — the FT reported recently that some Trump administration official is pushing to kick Canada out of the Five Eyes signals intelligence-sharing pact.

Now okay, the Americans provide the bulk of signals intelligence to allies. There’s no surprise about that. But if you lost the 25% provided by non-US allies, it will cost the US a hell of a lot more to get a lot less. It will lose coverage in places like Cyprus, in the South Pacific, all kinds of things in the high north, in the Arctic in the Canadian case. This administration just doesn’t understand that in the slightest.

Michael Horowitz: Traditionally what we’ve seen is regardless of what political hostility looks like, things like intelligence sharing in something like the Five Eyes context continues — in some ways the professionals continue doing their jobs. If you see a disruption in that context, that would obviously be a big deal.

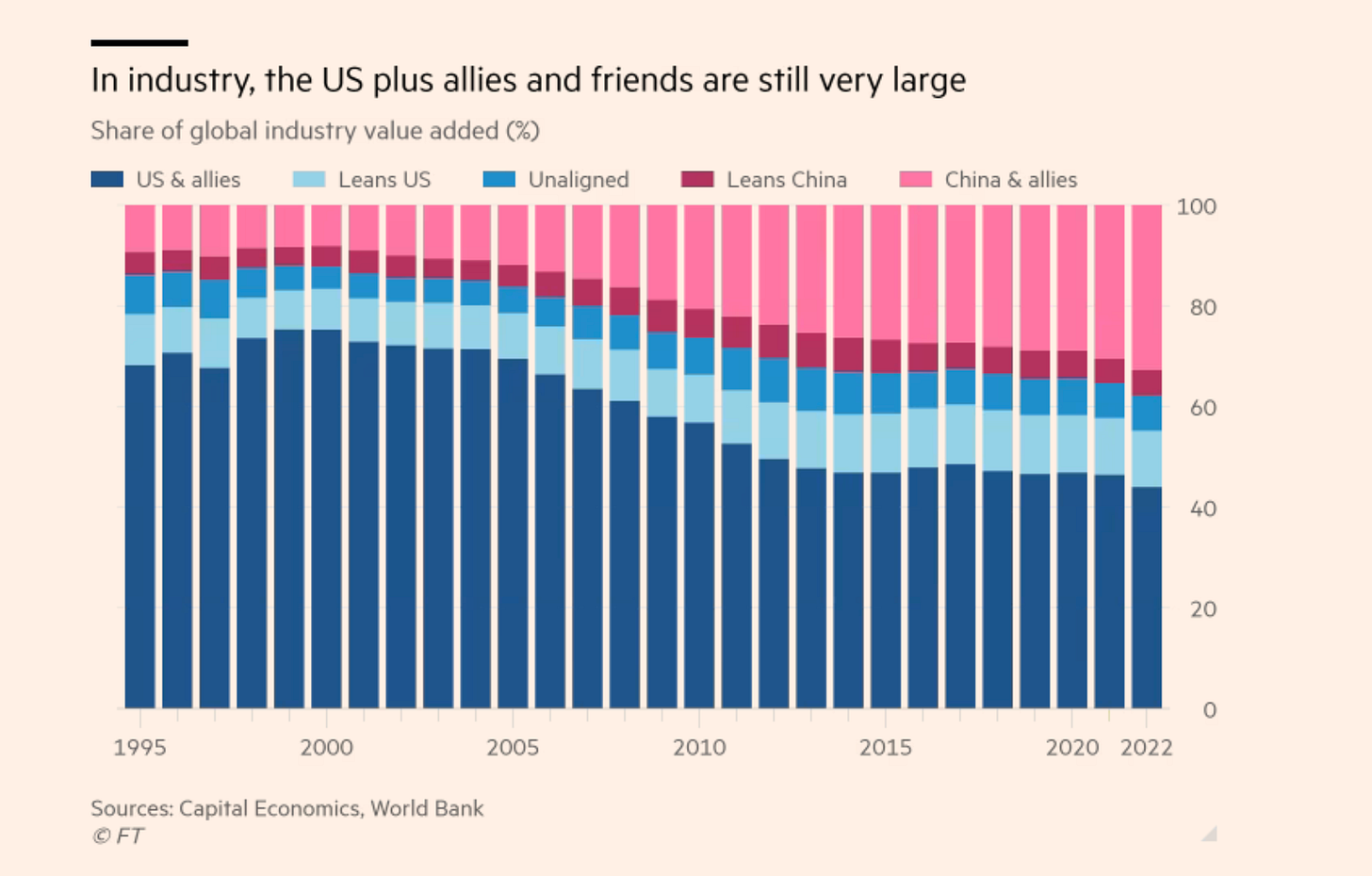

Jordan Schneider: Just staying on the Warsaw Pact versus NATO in 2025 today, America plus its allies accounted for nearly 70% of global GDP during the Cold War. The economic outflows that were needed to sustain Soviet satellites eventually bankrupted the USSR. America isn’t facing anything resembling that situation by stationing 10,000 people in Poland and South Korea.

Michael Horowitz: We are in a competition of coalitions with China, and it is through the coalition that we believe we can sustain technological superiority, economic superiority, military power, et cetera. Look at something like semiconductors and the role that the Netherlands plays in those supply chains, that Japan plays in those supply chains. There are interconnections here. We have thought that we will win because we have the better coalition.

Shashank Joshi: That’s an interesting question to ask more conceptually — does this administration want a rebalancing of its alliances or does it want a decoupling? You could put it in terms of de-risking and decoupling if you want to echo the China debate here. Does it simply want more European burden-sharing? But fundamentally the US will still maintain a presence in Europe, underwrite European security, and provide strategic nuclear weapons as a backstop. That is what many governments are trying to tell themselves.

The more radical prospect is that whilst there are some people who envision that outcome — Marco Rubio, Mike Waltz (the National Security Advisor), and John Ratcliffe (the head of the CIA) — the President and many of the people around him view things in considerably more radical terms. It’s more of a Maoist cultural revolution than a kind of “I’m Eisenhower telling the Europeans to spend more.”

Jordan Schneider: There’s this quote from Marco Rubio that’s really stuck with me from a 2015 Evan Osnos profile where he talks about how he has not only read but is currently rereading The Last Lion, which is this truly epic three-part series. The middle book alone is most famous, which is what Rubio was referring to, where Churchill saw the Nazis coming when no one else did and did everything he could in the 30s to wake the world up and prepare the UK to fight.

Rubio is referring to this moment by comparing it to how he stood up to the Obama administration when they were trying to do the JCPOA nuclear deal with Iran. To go from that to having to sit on TV and blame Ukraine for starting the war, I think is just the level of cravenness. There are different orders and degrees of magnitude.

Shashank Joshi: You have to think about this not in terms of a normal administration in which people do the jobs assigned to them by their bureaucratic standing. You have to think about it like the Kremlin, where you have power verticals, or an Arab dictatorship where you have different people reporting up to the president. Think of this like in Russia, where you have Sergey Naryshkin, the head of the Foreign Intelligence Service, who may say one crazy batshit thing, but actually has no authority to say it. In which Nikolai Patrushev may say another thing, in which Sergey Lavrov may lay down red lines, but they have no real meaning because there’s a sense of detachment from the brain, the power center itself. Ultimately, it’ll still be Putin who makes the call. I think it’s a category error if we try to think about this administration as a normal system of American federal government.

Michael Horowitz: I will say, I can’t believe I’m now going to say this, but let me push back and say that there’s a lot of uncertainty about what the Trump administration wants to accomplish here, given the way they have embraced the notion that Trump is a master negotiator. To be professorial about it, in a Thomas Schelling “threat that leaves something to chance” way, or like madman theory kind of way, they think that there’s a lot of upside here from a bargaining perspective.

Most of Trump’s national security team is not yet in place. We just had a hearing for the Deputy Secretary of Defense yesterday. Elbridge Colby, who’s the nominee for undersecretary, has a hearing coming up, I think either next week or the following week. So a lot of the team is still getting in place.

Jordan Schneider: The thing about Trump 1.0 is there weren’t wars like this. You had two years of sort of normal people who were basically able to stop Trump from doing the craziest stuff. Then the COVID year was kind of a wash. But Trump 2.0 matters a lot more, it’s fair to say, over the coming four years than it did 2016-2020.

Shashank Joshi: It’s much more radical. In the first term, John Ratcliffe had his nomination pulled as DNI because he was viewed as inexperienced and not up to the job. Today, John Ratcliffe looks like Dean Acheson compared to the people being put into place. We have to pause and make sure that we recognize the radicalism of what is being put into place around us.

When you look at the sober-minded people who thought about foreign policy — and I include amongst this people I may disagree with, like Elbridge Colby, who will be probably the Pentagon’s next policy chief — what is the likely bureaucratic institutional political strength they will bring to bear when up against those with a far thinner history of thinking about foreign policy questions?

Jordan Schneider: I haven’t done a Trump-China policy show because I don’t think we have enough data points yet. But what, if anything, from the past few weeks of how he’s thinking and talking about Russia and Ukraine, is it reasonable to extrapolate when thinking about Asia?

Shashank Joshi: Two quick things. One is I see significant levels of concern among Asian allies. The dominant mood is not, “Oh, it’s fine, they’re going to just pull a bunch of stuff from Europe, stick it into Asia and it’ll be a great rebalancing.”

Number two, I think this is important: there is a strong current of opinion that views a potential rapprochement with Russia as being a wedge issue to drive between Russia and China, the so-called reverse Kissinger. Jordan, you know much more about China than I do. I’m not going to comment further on that, but I will say I believe it is an idea that is guiding and shaping and influencing current thinking on the scope of a US-Russia deal.

Michael Horowitz: You certainly have a cast of officials who are pretty hawkish on China, which will be a continuation in some ways of the last administration and the first Trump administration. I think the wild card will be the preferences of the president. There was a New York Times article a few days ago that talked about Trump’s desire for a grand bargain with China — his desire to do personal face-to-face diplomacy with Xi as a potential way to obtain a deal.

Now I think the reality is that every American president that has tried to do that kind of deal, whether in person or not over the last decade, has found that there are essentially irreconcilable differences. There’s a reason why there is US-China strategic competition and why that has been the dominant issue in some ways of the last several years and probably will be over the next generation. But Trump may wish to give it a shot — and it sounds like, at least from that article, that he might.

Jordan Schneider: We’ve also had every administration in the 21st century try to start their term by trying to reset relations with Russia. “Stable and predictable relationship” was Biden’s line. Maybe this stuff is just a blip, but I think Shashank’s right. We’re in really uncharted territory.

We continue…

AI as a general-purpose technology with both direct and indirect impacts on national power,

Whether AGI will cause instant or continuous breakthroughs in military innovation,

The military applications of AI already unfolding in Ukraine, including intelligence, object recognition, and decision support,

AI’s potential to enable material science breakthroughs for new weapons systems,

Evolution of drone capabilities in Ukraine and “precise mass” as a new era of warfare,

How China’s dependence on TSMC impacts the likelihood of a Taiwan invasion,

Whether AGI development increases the probability of a preemptive strike on the US,

How defense writers and analysts help shape policy and build bureaucratic coalitions,

Ukraine as a real-world laboratory for testing theories about warfare, and what that means for Taiwan’s defense.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the future of war. There is this fascinating tension that is playing out in the newly national security-curious community in Silicon Valley where corporate leaders like Dario Amodei and Alex Wang, both esteemed former ChinaTalk guests, talk about AGI as this Manhattan Project-type moment where war will never be the same after one nation achieves it. What’s your take on that, Mike?

Michael Horowitz: There’s a lot of uncertainty about the way advances in frontier artificial intelligence will shape national power in the future of war. I’ve been, historically, extremely bullish on the impact of AI from a national defense perspective. I remember when Paul Scharre and I and a couple of other people were in a small conference room at CNAS with basically everybody in Washington D.C. that cared about AI and national security. Now it’s obviously a much bigger space and that’s a good thing.

But I think the notion that AGI will inherently transform power in the future of war in that kind of context makes a couple of assumptions that it’s not clear to me are correct. The first is that there’s essentially a binary. You don’t have AGI and then you have AGI, and when you get there, there’s this magical jump in capabilities, which essentially means that you can then solve all sorts of problems you have been trying to solve that you couldn’t solve before. So it leads to a dramatic step change in capabilities.

That might be true. It also might be true that you have continuing growth in AI capabilities and we kind of bicker about whether they constitute AGI or not, like over time, in part for very clear human psychology reasons. And so you never have that one specific moment, yet you still have ever-increasing frontier AI capabilities that militaries can then potentially adopt.

This points out the other assumption: that the technical breakthroughs are the same thing as government adoption, which I think everything we know about the history of military innovation suggests is incorrect. The thing that I worry about the most is that US companies lead the world in AI breakthroughs, but the US Government lags in effective adoption for a variety of reasons that have to do with legacy bureaucracy, budgeting systems, relationships between the executive and Congress — all sorts of normal bureaucratic politics issues which could make adopting those breakthroughs quickly very difficult. Whereas maybe the PRC gets there, maybe China gets there later, but due to the way their system sets up, adopts the upside faster.

Jordan Schneider: All right, that was a lot that I want to unpack relatively slowly. So first, we have AI evals for how good it is at coding and math and whatever. What is the AI eval that will convince Mike Horowitz that this is the next stealth bomber, the next nuclear weapon or what have you?

Michael Horowitz: I just think that’s the wrong way to think about it. AI is a general purpose technology, not a specific widget. If what we are looking for is the AI nuclear weapon or the AI stealth bomber, I think we’re missing the point.

When general purpose technologies impact national power, they do so directly and indirectly. They do so directly through, “All right, we have electricity, now we can do X,” or, “We have the combustion engine now we can do X.” They do so indirectly through the economic returns that you get, which then fuel your ability to invest in the military and how advanced your economy is. I think AI is likely to have both of those characteristics — arguably is already having both of those characteristics.

The thing that’s not entirely clear yet is whether there’s essentially a linear relationship between how advanced your AI is and what the national security returns look like. Part of that is informing my view of the bureaucratic politics here because I view adoption challenges as the biggest ones for the national security community in the United States.

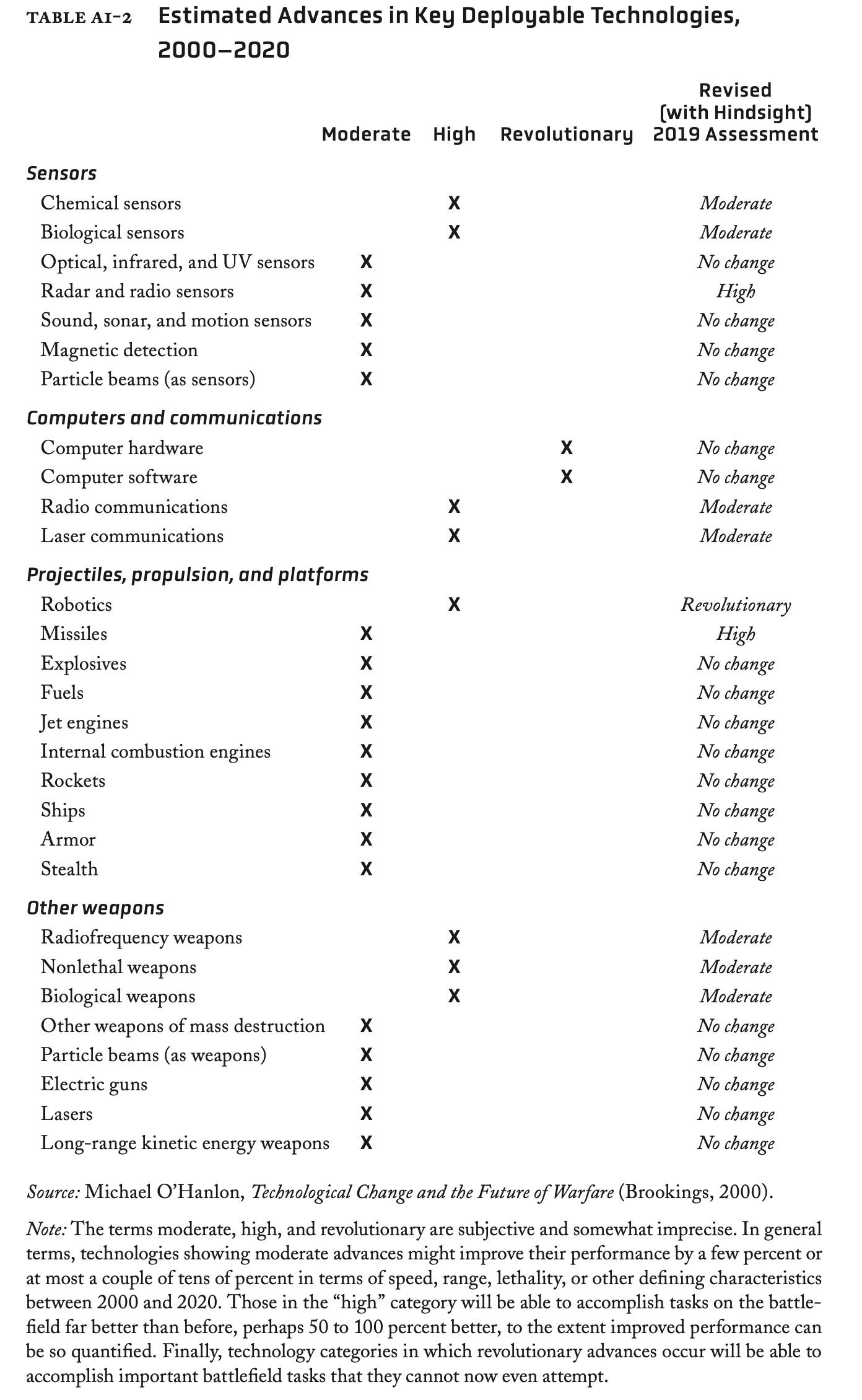

Jordan Schneider: Just to stay on defining terms, the direct applications we’re talking about, like the AI for science — we’re still in the very early phases, but there’s a really fun book by Michael O’Hanlon called “The Senkaku Paradox,” where at the end of it, he has this very cool table of all of the different vectors on which technology can get better over a 5, 10, and 20-year horizon. Show me some crazy material science breakthroughs that you can put in weapon systems, and I will be convinced that this stuff is really real and going to matter on a near-term horizon on the battlefield.

But I think the Dario Amodei framework of “this is going to radically change things in two to three years” strikes me as really not grappling with the challenges both on the scientific side as well as on the adoption side. Maybe Shashank, before we do adoption, anything on what this can potentially unlock that we would want to?

Shashank Joshi: Yes. I think we could split the applications of that general-purpose technology up a million different ways. The way I have tended to do it in my head, which is not novel — it’s probably plagiarized from people like Mike long ago — is thinking about insight, autonomy, and decision support.

Insight is the intelligence applications. Can you churn your way through satellite images? Can you use AI to spot all the Russian tanks?

Autonomy is, can you navigate from A to B? Can this platform do something itself with less or no human supervision or intervention? The paradigmatic case today, which is highly impactful, is terminal guidance using AI object recognition to circumvent electronic warfare in Ukraine.

The third interesting thing, which I think is the bit that Mike knows about — you’ve been talking about it, but my readers, it’s a challenge to get readers and even editors as interested in it — which is decision support. This includes things that nobody really understands in the normal world: command and control. The ability of AI to organize, coordinate, synchronize the business of warfare, whether that’s a kind of sensor-shooter network at the tactical level for a company or a battalion, or whether it’s a full theater-scale system of the kind that European Command, 18th Corps, and EUCOM has been assisting Ukraine with for the last three years.

This involves looking across the battlescape, fusing Russian phone records, overhead, radio frequency, satellite, IM satellite returns, synthetic aperture radar images, all kinds of other things into a coherent picture that’s then used to guide commanders to act more quickly and effectively than the other side. That’s difficult to define. But if we’re talking about transformative applications, I think that is really where we need to be looking carefully. And we can say more on that.

Michael Horowitz: I think that’s absolutely right. General Donahue is a visionary when it comes to what AI application can look like for the military today, and in trying to at least experimentally integrate more cutting-edge capabilities.

To the Dario point though, it’s all a question of timeframe and use cases. If you imagine AGI as instantly having access to 10,000 Einsteins who don’t sleep and don’t get tired and are just there doing the work for you from a research and development perspective all the time, then that’s going to lead to lots of breakthroughs that will generate specific use cases.

These could lead to new material science breakthroughs that decrease radar cross-sections, new advances in batteries that finally mean the dream of directed energy becomes more of a reality, advances in sensing in the oceans that create new ways of countering submarines. It could lead to all sorts of different kinds of things. The challenge is it’s difficult in some ways, ex-ante, to know exactly which you’ll get when.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, I mean, I think Dario would say that your framework, Shashank, is the weak sauce and what he’s talking about is an entirely new paradigm. This may be our transition to Ukraine today because it is important to understand what is happening now, particularly since we have had a high-intensity war for three years with two countries that are on or pretty close to the technological frontier of all this stuff. Just like over the course of World War I, particularly on the Western front, it takes a while to reach the frontier of what today’s technology can give you. There are certain things which are happening and certain sci-fi things that people may have predicted would have happened in 2020, which are not.

Shashank Joshi: The autonomy piece is super interesting because of the pace of change. To sum this up, when I was talking to Ukrainian first-person view (FPV) strike operators — my colleagues were talking to them maybe 18 months ago — they were saying that if you are a member of an elite unit with loads of training, you can get the hit rate up to 70-75%. But if you’re an average strike pilot, this is not easy. Sticking those goggles on, navigating this thing — you don’t know when the jamming is going to kick in and cut the signal. You have to get it just right, and you’re getting like 15-20% hit rates maybe.

What I am seeing with the companies and entities building these AI-guided systems for the final 100 meters, 200 meters, 300 meters, and increasingly up to 2 kilometers in some cases, is that the engagement range is going up. You can home in on the target beyond the range of any plausible local jamming device. That’s a huge deal. More importantly, the hit rate you’re getting is 80% plus. That’s phenomenal. That changes the economics, the cost per kill; that changes the economics of this from an attrition basis.

There are all these interesting ripple effects. Suddenly, if you have a device I can give to Jordan and you, and we can say, “Hey, fly this thing towards that Russian tank,” we don’t have to spend weeks training you up. You can achieve this with like 30 minutes of training. Think about what that unlocks for a force, particularly sitting here in Europe where we have these shrunken armies with no reserves, with the manpower requirements as well with the training times to bring new people in when you have attrition in a war in the first round.

This little tactical innovation — terminal guidance, AI-enabled — looks very narrow, but it has all these super interesting and consequential ripple effects on the economics of attrition, the cost per kill, lethality levels, the effectiveness of jamming, and on manpower and labor requirements. That’s why it’s so important to get into the weeds and look at these changes.

Michael Horowitz: We’re seeing at scale something that we kind of thought might happen, but it just always been theoretical rather than something real. The argument for why you would need autonomy to overcome electronic warfare has been obvious for decades. When they were questioning if the technology is there or if we want to do it this way, there were different kinds of approaches.

What we’ve seen is that when you are fighting conventional war at scale, if you want to increase your hit rate and overcome jamming when facing electronic warfare, you can update software to try to counter the jamming. You can try to harden against jamming, and although it increases costs, you can use different concepts of operation to try to get around it, to sort of fool the local jammers.

But to the extent that autonomy becomes a hack that lets you, to Shashank’s smart point, train and operate systems more effectively in much less time — that’s a game changer, and it’s not one that we should expect to be confined there. Imagine all of the Shaheeds that Russia fires at Ukraine with similar autonomous terminal guidance out to a couple of kilometers. Imagine all sorts of weapon systems with those kinds of capabilities. We’re seeing this at scale in Ukraine in a way we just had imagined.

To be clear, it’s not just in the air. Let me now just give my 15-second rant on the term “drone.” We are currently using the term “drone” to refer to a combination of cruise missiles, loitering munitions, ISR platforms, and uncrewed aerial systems that themselves launch munitions. All of those are getting called drones right now, even though we actually have correct names for them. It might be helpful if we used those names since we’re talking about different capabilities, essentially. But yeah, plus one to everything.

Shashank Joshi: Mike, do you want me to start using terms like UAS, UUVs? I’m going to get sacked if I start using all those acronyms.

I’d like to ask you about something since you’ve raised the issue of different domains. One of the questions I often get asked by readers is: where are all the drone swarms? Where are the swarms that we were promised? Maybe this is a kind of ungrateful thing because we bank a bit of technology and we are desensitized to it and then we forget everything else.

What interests me is, when writing about the undersea domain a while ago and submarine hunting, I was struck by how difficult it is — this is obvious physics — to communicate and send radio frequency underwater. Radio waves don’t penetrate water very much, if at all. Acoustic modems and things like that are very clunky. So the technologies we have relied on for things like control signals, navigational signals, oversight in the air domain operate very differently in places where signals don’t travel as much — the curvature of the earth or in the water. Do you think that uncrewed technology and autonomy operates in some kind of fundamentally different way in those domains or will it be less capable in those places?

Michael Horowitz: That is a great question. Let me give you a broad answer and then the answer to the specific undersea question.

We’ve essentially entered the era of precise mass in war, where advances in AI and autonomy and advances in manufacturing and the diffusion of the basics of precision guidance mean that everybody essentially can now do precision and do it at lower cost. This applies in every domain — it applies in space, in air for surveillance, in air for strike, to ground vehicles, and can apply underwater and on the surface now. The specific way that it plays out will depend on the specifics of the domain and on what is most militarily useful.

For example, if the question is “where are the swarms we were promised?” and what we end up with is a world where one person is overseeing maybe 50 strike weapons that are autonomously piloting the last two kilometers toward a target, there may be actually military reasons why we don’t want them to communicate with each other. If they communicated with each other, that would be a signal that could be hacked or jammed, which then gets you back into the EW issue that you’re trying to avoid. There’s an interaction in some ways between the “swarms we were promised” and some of the ways that you might want to use autonomy to try to get around the electronic warfare challenge.

This points to the huge importance of cybersecurity in delivering essentially any of this. Part of the issue is that swarms potentially are vulnerable to some of the same issues that face FPV drones and other kinds of systems in different kinds of strike situations. It wouldn’t be surprising to me if you then see a move more towards precise mass in the context of autonomy without swarming in a world where you think that you’re getting jammed.

Now underwater, you absolutely have the physics issue that you’ve pointed out — communication underwater is just more difficult. To the extent that something like swarming requires real-time coordination, that becomes even more difficult the further away things are from each other. It wouldn’t be surprising then that the underwater domain would be challenging here.

To take it back to the AGI conversation we were having, two notes are relevant here. One, the “where were the swarms we were promised” question reminds me that how we define artificial general intelligence often is a moving target. We’re constantly shifting the goalposts because once AI can do things, we call it programming. Artificial general intelligence is always the thing that’s over the horizon.

Going back to my belief that there might not be one AGI moment, it reflects that way that the definition of AI has tended to be a moving target. But specifically, if you’re in the “AI will transform everything” paradigm, one of the things you would probably try to use AGI to do that would have transformative impact would be to solve some of these communication issues in the undersea domain that can potentially limit the utility of uncrewed systems in mass undersea. That’s an example essentially of a science problem that then maybe major advances in AI help you address when you have paradigm-shifting AI.

Jordan Schneider: All right, Mike. Slightly adjacent to this, there are two odd theories why a US-China-Taiwan war could kick off. One is China’s dependence on TSMC being a really important independent variable in their willingness to go to war. Second, this idea that if one side gets AGI, then the other would need to do a preemptive strike to stop their adversary — I don’t know, like creating Dr. Manhattan or something.

Michael Horowitz: Those are great questions. A lot of what we know from the theory and reality of the history of international relations and military conflicts suggests that war in either case would be pretty unlikely.

Let me start with the Taiwan scenario. I am extremely nervous, to be clear, about the prospect of a potential conflict between China and Taiwan. There is real risk there. But the notion of China essentially starting a war with Taiwan over TSMC would be kind of without precedent. Put another way, there are lots of paths through which we could end up with a war between China and Taiwan. The one that keeps me up at night is not an attack on TSMC.

Jordan Schneider: Ben Thompson just wrote a piece where he is defining as an important independent variable in Beijing’s calculation of whether or not to start a war over Taiwan, to what extent they are reliant on Taiwanese fabs to function their economy or whatever. How do you think about that line of argument in a broader historical context?

Michael Horowitz: The best version of the argument, if you wanted to make it, is probably that if China views itself as economically dependent on Taiwan, it would then seek to figure out ways to get access to the technology that it needs from Taiwan. You could imagine that effort happening in a couple of different ways.

One is to actually attempt to mimic what TSMC does, which obviously they’re already attempting to do. Another would be attempting to coerce Taiwan in one way or another to try to get better access to TSMC. But starting a war with Taiwan where tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people are likely to die, and which could trigger a general war with the United States and other countries in the Indo-Pacific over the fabs — I think that’s relatively unlikely since China would have lots of other ways to try to potentially get access to chips that they need.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, so you keep coming back to the straw man, which isn’t even the straw man I’m pointing at because I think that’s the dumber version of the straw man — go into TSMC to take the chips. But there’s another line of argument that as long as China still needs TSMC and is able to buy NVIDIA 5-nanometer or 3-nanometer NVIDIA chips and needs the output from those TSMC fabs to run its economy in a normal, modern way, then that would drive down the likelihood of China wanting to start a conflict.

Michael Horowitz: There’s certainly an argument in that direction, which is to say that economic dependence could generate incentives to not start a conflict as well. My belief tends to be that the probability of war between China and Taiwan will be driven by broader sociopolitical factors.

Jordan Schneider: I would also agree. Putting on my analyst hat for a second, the domestic Chinese political dynamics, whatever’s happening from a policy perspective, whatever’s happening in domestic Taiwanese politics — the perception of America’s willingness or Japan’s willingness to fight for Taiwan all seem to me to be orders of magnitude more relevant than the percentage share of high-end chips that China is consuming from SMIC versus TSMC.

But let’s come to the other version of this — “My adversary is about to get AGI, so therefore I will want to Stuxnet their data centers and Operation Paperclip all their AI engineers and start World War III over a breakthrough in artificial intelligence.” Where are you on that one, Mike?

Michael Horowitz: The argument is insufficiently specified, and I will say my views on this could change. For a situation in which, say, China would attack the United States because it feared the United States was about to reach AGI, that presumes essentially a couple of things.

First, it presumes that AGI essentially is some kind of finish line in a race or binary where once you get there, there’s a step change in capabilities and that there’s no advantage to being second in that case — that it’s a step change of capabilities that would immediately negate everything that everybody else has. Or I guess that’s two assumptions: one is that it’s binary; the second is that it’s a breakthrough that negates everything that everybody else has.

The third assumption is that advances are transparent, such that the attacker would know both what to hit and when to hit it to have maximum impact. There are a lot of reasons to believe that all of those assumptions are potentially incorrect.

It’s not clear, despite enormous advances in AI that are transforming our society and will continue, that there will be one magical moment where we have artificial general intelligence. Frankly, the history of AI suggests that 15 years from now we could still be arguing about it because we tend to move the goalposts of what counts as AI. Since anything we definitively have figured out how to do, we tend to call programming and then say that it’s in support of humans.

It’s also not clear that these advances would be transparent and that countries would have timely intelligence. You need to be not just really confident, but almost absolutely certain that if somebody got to AGI first, you’re just done, that you can’t be a fast follower, and probably that it negates your nuclear deterrent.

If you believe that AGI is binary, that if you get it, it negates everything else, and that there’ll be perfect transparency — in that case, maybe there would be some incentive for a strike. Except that military history suggests that these are super unlikely.

What we’re talking about in this context is a bolt from the blue — not the US and China are in crisis and on the verge of escalation and then there’s some kind of strike against some facilities. We’re talking about literally being in steady state and somebody starts a war. That’s actually pretty unprecedented from a military history perspective.

Leaders tend to want to find other ways around these kinds of situations. If you even doubted a little bit that AGI would completely negate everything you have, then you might want to wait and see if you can catch up rather than start a war — and start a war with a nuclear-armed power with second strike capabilities. It’s so dangerous.

Jordan Schneider: I am sold by arguments one and three. If the story of DeepSeek tells you anything, it’s not even fast following like three years with the hydrogen bomb in the Cold War; it’s fast following like three months with a model you can distill.

So if you’re that patient and if it’s not really this zero-to-one thing where all of a sudden America invents time travel — but maybe the more relevant data point is less like America nuking the Soviet Union in 1946 just because we can, but something that looks a lot more like Iran and Israel in the 2000s and 2010s. You don’t literally have missiles being fired and airstrikes, but you have this increasingly nasty world of targeted assassinations and Stuxnet-like hacking of facilities.

What is now a pretty kind of happy-go-lucky world in San Francisco when it comes to developing these AI models becomes a lot more dark and messy. Mike, what could trigger that potential timeline, and what does that look like once both parties presumably start to play that game?

Michael Horowitz: Let me be more dire and say, what’s the difference between that and the status quo? Obviously there’s a difference if we’re talking about assassination attempts and those kinds of things. But every AI company around the world, including PRC AI companies, is probably under cyber siege on a daily basis from varieties of malicious actors, some of them potentially backed by states trying to steal their various secrets.

To me, this falls into a couple of categories. One is cyber attacks to steal things — hacking essentially for the purposes of theft. A second would be cyber attacks for the purposes of sabotage, like a Stuxnet-like situation. A third would be external to a network, but physical actions short of war — espionage-ish activities to disrupt a development community.

On the cyber attack aspect, there is a tendency sometimes to overestimate the extent to which there are magic cyber weapons that let you instantly intrude on whatever network you want. Are there zero days? Yes. Are cyber capabilities real? Yes. Many governments, including the United States government, have talked about that, but I’m not sure it’s as easy to say “break into a network” that is, to be clear, pretty hardened against attack, and just flip a switch like, “oh, today we’re going to launch our cyber attacks."

There are both effectiveness questions about some of those things, frankly. But also those networks are constantly being tested.

Regarding Stuxnet-kind of attacks — that was really hard. Stuxnet is probably the most successful cyber-to-kinetic cyber attack arguably in known history. It’s this enormous operational success for Israel against Iran.

Jordan Schneider: But the difference with Stuxnet versus what we’re talking about, right, is that a data center in Virginia or Austin is much more connected to the world. They’ll hire a janitor. It’s not like in a bunker somewhere.

Michael Horowitz: Those are more accessible, but there are also more data centers. This gets into commercial technology where targeting any one data center in particular is not likely to grind all AI efforts to a halt.

Frankly, if there is one AI data center in particular where there is widespread acknowledgement that what happens at that physical location will be decisive for the future of global power, that’s going to be locked down. The company will have incentives to lock it down, just like defense primes have incentives to lock their systems down, even if we’re not talking about defense companies. Companies like Microsoft and Google have incentives to lock down non-AI capabilities as well.

My point isn’t that there won’t be attempts and even that some of those attempts won’t succeed, but there’s sometimes a tendency to exaggerate the ease of attack and its structural impact. In a world where we’re talking about hitting a very accessible facility in Virginia, that means there’s probably similar accessible facilities in other places that also can potentially do the job.

Now the toughest scenario is the espionage one where you’re talking about essentially covert operations targeting companies. It wouldn’t surprise me if some of those companies are intelligence targets for foreign governments. The challenge analytically is that these arguments quickly enter the realm of non-falsifiability.

If I tell you that I think this kind of espionage or that kind of espionage wouldn’t be that likely, you could say “well what about this, what about this?” And we’re not going to be able to resolve it with facts. Non-falsifiable threat arguments make me nervous analytically. Maybe this is the academic in me that makes me want to push back a little bit because I feel like if an argument is legitimate, we should be able to specify it in a clearly falsifiable way.

Jordan Schneider: Like what? Give me the good straw man of that.

Michael Horowitz: The best strawman argument would be if you could basically demonstrate that the PRC is not really trying to target for collection varieties of AI companies and that it would be relatively easy for them to do so. That would raise the question of why they’re not doing that now. Then we get back to the question about what’s the point at which they would start those kinds of activities.

They would need to have enough information that they believe some company or set of companies is getting close to AGI, but not enough that they would have done something previously — assuming they’ve got good capabilities on the shelf that they would pull off if they have to.

The non-falsifiable part is about to what extent they could ramp up attacks, to what extent there would be defenses against those attacks, and to what extent those non-kinetic strikes would actually meaningfully delay the development of a technology. Another way of saying this — my prior is that there’s lots of espionage happening all the time. I want to see more specificity in this argument about what exactly folks mean when they talk about escalation.

Jordan Schneider: One of the things that has been remarkable about China, at least how it deals with foreigners, is that you haven’t seen what Russia did with all these targeted assassinations. The sharpest we’ve gotten, at least with dealing with white people, has been the handful of Canadians who were grabbed and ultimately let go after a few years in captivity following the Meng Wanzhou arrest.

People are very focused on China starting World War III out of the blue. But there are also world states in which China becomes much more unpleasant while not necessarily kicking off World War III.

Michael Horowitz: I’m a definitive skeptic on the “China starts World War III over AGI” point. I buy the notion that China could become more unpleasant as we approach some sort of AGI scenario — including non-kinetic activities, espionage, etc. I tend to maybe not view those as decisive as some others do potentially.

You’re right that they certainly could become a lot more unpleasant. If the question is why they haven’t already, the answer is probably twofold. One, there’s an attribution question — suppose Chinese espionage involved doing physical harm to AI researchers or something similar. If they were caught doing that, they’ve now potentially started a war with the United States, and they’re back to the reason why they wouldn’t launch a military strike in the first place.

If it’s non-attributable, then the question is exactly how much are they going to be able to do? I wonder whether there is something about their broader economic ties with the United States that maybe makes some of the worst kinds of these activities less likely in a way that is less troubling to Russia.

Jordan Schneider: This is a decent transition to precise mass in the China-Taiwan context. What can and can’t we infer about military technological innovation in Ukraine to what a war would look like over the next few years?

Michael Horowitz: It’s not necessarily the specific technologies, but it is the vibes. By that, what I mean is the advances in AI and autonomy, advances in manufacturing, the push for mass on the battlefield that we see already in publicly available documents and reporting on how the PRC is thinking about Taiwan. We see that already in the US in the context of Admiral Paparo and Indo-Pacom and the Hellscape concept or something like the Replicator initiative in the Biden DoD — and full disclosure, I helped drive that, so I certainly have my biases.

We see that if you look at some of the systems that Taiwan has been acquiring over the last couple of years. You essentially have a growing recognition that more autonomous mass, or what I’d call precise mass, will be helpful in the Indo-Pacific. It’s unlikely to be the exact same systems that are on the battlefield in Ukraine, but variants of those scoped to the vastness of the Indo-Pacific.

Shashank Joshi: I have a few thoughts on this. One way to think about what Mike is saying is for any given capability, you can have more intelligence that is defined however you like, whether that’s in terms of autonomy or capacity to do the task on the edge at a lower price point.

That capability could be a short 15-kilometer range small warhead strike system in the anti-infantry role. It could be a 100-kilometer system to take out armor with bigger warheads, or it could be significantly longer range systems that have to be able to defeat complex defensive threats. Obviously, the third of those things is always going to be more expensive than the first.

What that revolution in precise mass, if it is a revolution (we can debate if that’s what it is), does is push you down. The capability per dollar is going up and up. That is the essential point.

Michael Horowitz: Just to be clear, that’s the reverse of what we saw for 40 years, where in the context of the precision revolution, you were paying more and more for each capability, whereas now we are seeing the inverse of that in the era of precision mass.

Shashank Joshi: Is the transformative effect comparable across each level of sophistication or capability or range? Are there specific things to FPV-type systems because they, for instance, rely on consumer electronics, consumer airframes, and quadcopters — they can draw upon a defense industrial base or an industrial base that has existed for commercial drones? Is it easier to have that capability revolution for intelligent precision mass at one end of the spectrum relative to building a jet powered system that has to travel significantly further, has to defeat defense mechanisms, may have to have IR thermal imaging, etc? Is a revolution comparable at each end?

Michael Horowitz: I was with you up until the end about defeating all of those systems, because the thing that’s so challenging about this for a military like the United States is it’s a different way of thinking about fighting. You’re talking about firing salvos and firing at mass as opposed to “we’re going to fire one thing and it’s going to evade all the adversary air defenses and hit the target."

Look at Iran’s Shahed 136. That’s a system that can go, depending on the variant, a thousand plus kilometers, can carry a reasonable size warhead that in theory could have greater or lesser levels of autonomy depending on the brain essentially that you plug into it. That’s not going to be as sophisticated a system as an advanced American cruise missile that costs $3 million or something. But it doesn’t have to be because the idea is that these are complements where you’re firing en masse to attrit enemy air defenses. Your more sophisticated weapon then has an easier path to get through. It’s just a different way of thinking about operating, and that creates all sorts of challenges beyond just developing the system or buying the system.

Shashank Joshi: That’s a really interesting point. This gets us to a phrase, Mike, that is very popular in our world and you and I have talked about this, which is the mix of forces that you have and specifically the concept of a high-low mix. It’s not just that small drones will replace everything. You have a high-low mix where you will have some, albeit fewer, very expensive, high-end capabilities that can perform extremely exquisite, difficult tasks or operate at exceptionally high ranges. Then you will have a lot more in quantity terms of lower-end systems that are cheaper, more numerous, and that will not be as capable — they can’t do things that a Storm Shadow cruise missile or an ATACMS missile can do, but they can do it at a scale the Storm Shadow can’t do or the ATACMS can’t do.

The most difficult concept when I’m writing about this for ordinary people who are maybe not into defense is explaining the mix, the interaction of those two ends of the spectrum. Here’s the difficult bit — pinning down what is the right mix. Do we know it yet? Will we know it? How will we know? Does it differ for countries? That’s where I’m struggling to understand all of this.

Michael Horowitz: It probably differs for countries and even within countries differs by the contingency. For example, if you are fighting, if you’re back in a forever war kind of situation and you’re the United States, then you might want a different mix of forces than if you’re very focused on the Indo-Pacific and on China in particular. What comprises your high-low mix probably changes.

The way that I’ve tended to think about this is you have essentially trucks, which are the things that get you there. Then you have brains, which is the software that we’re plugging in. And then you have either the sensor or the weapon or the payload piece. In some ways, what I think we’re learning from Ukraine that is applicable in the Taiwan context is that sometimes it matters a lot less what the truck is than what the brain is.

Shashank Joshi: The other thing that I struggle to get across is the relationship between the “precise” bit and the “mass” bit, particularly the role of legacy capabilities in this. The great conflict I see today is in the artillery domain. Do strike drones replace or supplant artillery? Strike drones now inflict the majority of casualties in Ukraine, not artillery, as was the case at the early phase of the conflict.

There is this really interesting line in — I think it’s in the British land operating concept or it’s in the British Army Review published a couple of years ago. I want to read it because it gets to something I’ve thought about. It says: “There is a danger that the enemy will be able to generate more combat echelons than we have sensors or high-end long-range weaponry to service.” That’s the point. You can have these wonderful AI kill chains that can do remarkable things, that can spot anyone moving, can feed that data back to your weapons. But if you don’t have the firepower to prosecute those targets and then keep prosecuting them week after week in a protracted conflict, you don’t have deterrence. That is what we are waking up to now.

Michael Horowitz: The important thing here is the notion that you didn’t need a high-low mix, that you could just go high, presumes short wars where you can just use your high-end assets and sort of shock and awe the adversary into submission. Whether we’re talking about a forever war situation or in the Indo-Pacific, if you’re fighting in a world of protraction, then you need much deeper magazines in all ways, including in your platforms frankly.

Maybe in that world AI is actually helping you with what you’re manufacturing and how you’re manufacturing and can deliver a bunch of other benefits on the battlefield. A big challenge here is that I don’t think these capabilities necessarily mean there’s no role for traditional artillery. Although if they can do the same job better at lower cost, then they will eventually displace those capabilities, or militaries that don’t adopt them will fall behind. We’re more at a complement than a substitute stage right now for those capabilities. But things could change.

The challenge right now for a military like the US is you have all these legacy capabilities, and maybe you wish to invest less in them to be able to invest more in precise mass capabilities, which is something I advocate. But then the question becomes what are you doing with those legacy capabilities and when across what timeframes?

This does tell you some things that are really important from a force planning perspective. For example, the “one ring to rule them all” approach to air combat that led to the F-35, where you’re just going to have one fighter that will operate forever and presumably be useful for every single military contingency. Turns out that means it’s optimized for none of them, and that generates a bunch of risk. One of the things that the new administration is probably going to be doing is figuring out how to address those risks. I don’t want to hate on the F-35 and its stubby little wings. Sorry, I’ll stop now.

Shashank Joshi: I’m really glad you raised F-35 because this gets to another one of my points of thinking. You said, “If it can do the same job,” right? What are the jobs it can and can’t do?

When you look at a simple mission, let’s take an anti-tank guided missile — it’s looking pretty clear to me that a kind of mid-range, low-cost strike system, one-way attack strike system is looking like it can do the job of an ATGM very effectively at significantly lower cost. Therefore, unless the ATGMs also get transformed, you’re going to see a supplanting of roles.

However, I’m also acutely conscious that we are thinking about some battlefields that are in some ways uncluttered. We’re looking at a stretch of the Donbas in which anything that moves is going to be the target that you want to hit — it’s going to be a Russian military vehicle. You’re not going to accidentally hit a school bus full of children. In the Taiwan Strait, you are using your object recognition algorithms to target shipping. You’re not accidentally going to hit something in the context of an amphibious invasion of Taiwan.

Michael Horowitz: Yeah, if the balloon goes up, it’s not like there’s lots of commercial fishing just chilling in the Strait.

Shashank Joshi: Well, and if it is, it’s probably MSS operatives. You’re fine. But in the air power situation too, right? You may be doing stuff like this. However, urban warfare is not going away. I’m imagining fights over Tallinn, over Taipei, over thin, cluttered, complex, multi-layered subterranean environments like Gaza, like Beirut, like places like that. I worry a lot more about the timeline over which autonomy will suffice.

To end on one last point before I spin off the RAF, the Royal Air Force believes that an autonomous fighter aircraft will not be viable prior to 2040. Now maybe that’s ultra conservative, but that’s based on some of the assumptions about the tasks they think it will need to do. I know you have your debate over NGAD and long-run capabilities. So are there limits to this process?

Michael Horowitz: The limits are how good the technology is. Frankly, I’ve argued this for years in the context of autonomous weapon systems. The last place that you would ever see autonomous weapon systems is in urban warfare. Not only whatever ethical moral issues that might surround that, but that’s just way harder to do than figuring out whether something is an adversary ship or an adversary plane or an adversary tanker in a relatively uncluttered battlefield.

Shashank Joshi: The second part was to do with the air picture, right? Countries are now having to decide what our air power is going to look like in 2040, and how much can we rely on the technology being good enough by then? You’re right, that is the question — will it be good enough? But you have to make the bet now. You have to make the judgment now because of the timelines of building these things.

Michael Horowitz: There are two questions there. One is how good is the AI technology? Frankly, even if Dario is overestimating how quickly we get to something universally recognized as artificial general intelligence — and just to be clear, dude’s way smarter than me and I’m not saying he’s necessarily wrong, just that there’s uncertainty here. He’s super smart and thoughtful.

Side note: the fact that CEOs of today’s leading companies post their thoughts and come on shows like this is super useful. Now that I’ve taken off my Defense Department hat and I’m back in academia, for understanding how a lot of the people designing cutting edge technology are thinking about it and its interaction with government policy and militaries — it’s actually incredibly useful that Dario, Sam Altman, and others post at length about their thoughts on these kinds of things.

If you’re talking about what the future of a next-gen aircraft airframe would look like or what a collaborative combat aircraft could do, my bet is that the militaries are underestimating how quickly AI will advance and the ability to do that. What they might be accurately assessing is, given the way the process of designing new capabilities works today and given today’s manufacturing capabilities, how long it would take to actually design and roll out a new system.

From a parochial American perspective, shortening that timeline is way more ambitious than what we were attempting to do with Replicator. I expect the new team actually will continue to push forward a lot of those things, whether they call it Replicator or not. You could have a scenario in which your AI is at a level that you believe you could have more autonomous operations of a collaborative combat aircraft, and you have some advances in manufacturing that mean you could produce maybe more of them at a slightly lower price point, but still be unable to do so before 2040 for various bureaucratic and budgetary reasons.

Jordan Schneider: All right, so we did a bit of scenario analysis of what Trump’s strategic outlook could be towards great power relations. It’s also worth doing some future forecasting of different pathways that they could go down from a defense technology innovation perspective. Maybe the best place to start is to look back over the past four years of where the Biden administration made progress, where it didn’t, and why it didn’t on certain dimensions. I don’t know how Mike is feeling looking back at his past four years of work.

Michael Horowitz: My bottom line would be I feel like we accomplished a lot in getting the ball really moving from a defense innovation perspective, specifically in moving toward greater investments in lots of important next generation capabilities like collaborative combat aircraft and varieties of precise mass through the Replicator initiative. But there is a lot more to be done.

It was a journey in two ways. One was bringing everybody along on that defense innovation journey to get to the point where folks bought into the importance of some of these emerging capabilities for the future of warfare, specifically in the Indo-Pacific. Then there’s what we could accomplish before the clock ran out.

To start with the first piece, taking everybody on the journey — nothing happens in the Pentagon without getting lots of people on board. It took a little while for there to be consensus on the state of the defense industrial base. If you look at varieties of think tank reports about what DoD should do differently, there are often all these suggestions like, “DoD needs to scale more of this system, scale more of that system, build more of that.” All of that is great, except that even if you fully fund really exquisite munitions like the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile or JASSM or something like that, you’re going to be really capacity constrained because those facilities just have limits. You can change those limits, but you can’t change those limits quickly.

What can you then do to scale capability relevant for the Indo-Pacific in the short term? The answer is precise mass capabilities — more attritable systems, more AI-enabled and autonomous systems, systems that maybe sometimes, but not always, are built by non-traditional companies. There’s a coalition of the willing that pushed through all of those in a bunch of different contexts, including Replicator, which DIU I think did a brilliant job of leading implementation of, and that generated some growing momentum.

But it also highlighted some real limits. Reprogramming 0.05% of the defense budget to fund multiple thousands of attritable autonomous systems for the Indo-Pacific under the first bet of the Replicator initiative required over 40 briefings to Congress, including a ton by the Deputy Secretary of Defense who’s really busy. Congressional oversight is really important, but that degree of effort required to reprogram essentially less than a billion dollars demonstrates a budget system unable to operate at the speed and scale necessary given the rate of technological change and given the threat that the US is under from Chinese military advances in the Indo-Pacific.

We did some good things. We moved the ball forward. I’m proud of some of the things that we did, but there’s a lot more work to be done.

Jordan Schneider: Ray Dalio had a quote today that America can’t produce manufactured goods cost-effectively. It’s pretty clear to me, the challenge of scaling up very advanced missiles or F-35s or whatever. But Shashank, if Ukraine can figure out how to build a million and a half drones a year, I’m pretty sure the US could if we decided. What do you think?

Shashank Joshi: Let’s unpack this a little bit. First of all, Ukraine is doing this under wartime conditions. It’s ripping up rules — not all of them, but a lot of them. It doesn’t have to worry about pesky things like health and safety standards, like “Can I build this explosive warhead facility next to this town?” You try doing that in the US or the UK or in Europe. The Ukrainians can get around that because they’re at war, it’s fine.

Secondly, what are they building these things with? The Ukrainian supply chain for UAVs and for lots of other things, including electronic warfare systems, is still full of Chinese stuff. They haven’t got it all out. Yes, there are companies beginning to find alternative supply chains and finding stuff from Taiwan and other countries, but the US government can’t do that. There’s the little pesky matter of the NDAA which prohibits you from just sticking Chinese components into all of your drones and building them out. So you have to get supply chains right. That’s problem number two.

Problem number three is to what standard are you building these things? Are you demanding that they can cope with this level of electronic warfare, radiation hardening, cybersecurity standards? Those are all the requirements being placed on UAS in many Western governments. I won’t speak directly to the US exactly, because Mike knows it better than I do, but certainly in my country I’m aware of this. The Ukrainians can build things to a satisfactory standard that would never stand up to the scrutiny of an accounting or auditing official in a Western country to the same way.

The final point on all of this is the level of mobilization for the defense industrial base is quite different. Ukraine has nationalized its IT sector. It had a brilliant IT sector before the war. It had some great technicians, tech-minded people, software-minded people. That is just not the case in most of our countries. We can’t nationalize our tech industry to go work to build software-defined weapons at a low cost very effectively and quickly. Those are some of the reasons I can see for the discrepancy. Mike, do you disagree?

Michael Horowitz: I think that is all correct. I’m probably more optimistic than you about the ability to build at low cost. Although what exactly you define as low cost? If we think about attritable as sort of replaceable kinds of systems, what’s attritable probably varies depending on how wealthy you are and how big your defense budget is. What’s attritable for the United States might be different than what is attritable for Ukraine.

There’s a lot of possibility to get lower cost systems. One example is last year there was an Air Force DIU solicitation for a low-cost long-range cruise missile that would be about $150,000 to $300,000 a pop. That’s way more expensive than an FPV drone in Ukraine, but that’s a lot more capability than an FPV drone in Ukraine. Given that existing systems, some of those existing systems cost a million dollars or more — if you can deliver that at what is a fraction of the cost, you’re buying back a lot of mass in a useful way.

The thing that I will be really interested to see, shifting actually to Europe for a second — if you look at what Task Force Kindred has done for Ukraine and some of the capabilities that have been scaled for Ukraine, my question is: when is the UK going to buy those for the UK? If these are militarily useful capabilities for fighting Russia on the battlefield in Europe, seems like something that might be useful for the United Kingdom’s military.

Or say the German company Helsing. When we were in Munich, Shashank, there was that announcement that they had produced 6,000 drones that were going to get sold to Ukraine — obviously in the context of like millions being produced. But presumably those 6,000 are pretty good from a quality perspective. Why isn’t Germany buying those drones then?

Shashank Joshi: Helsing is a really good example, Mike. In Ukraine, distributed in Ukrainian manufacturing facilities, they are building these UAVs where the hardware standardization is not completely standardized. The software has to adapt for the different airframes being built by different producers. But they’re good enough, they’re doing a good job, they’re making a difference, they’re producing Lancet-like capability at considerably lower cost as far as I understand it.

But Helsing is also building drones for NATO countries in southern Germany in its own factories. The advantage is that it controls the supply chains. It can standardize the process, it can build software-defined weapons in ways where the hardware is optimized to take that on — in the way that Tesla once built other people’s cars and put its code in them. But since that initial phase, it’s built its own hardware because it’s easier to build a software-defined car if you do it yourself. But it’s going to be more expensive and it’s not going to be as cheap and quick and easy as the Ukrainian manufacturing. I believe there are some trade-offs that you see even within the same company.

Michael Horowitz: Absolutely. That also is why you need more open architecture all around and why in some ways the government needs to own more of the IP. If you think about what I said before about trucks and brains — if you’re buying a truck that only can have a brain from the same company, then you’re locked into a manufacturing relationship that’s almost necessarily going to generate higher costs over time than if you can swap out the brain over time with something that might be more advanced. Frankly, whether it’s lower cost or not, it’s probably a better idea to be able to swap it out.

This reflects differences in not just the defense industrial base, but in how the US and western militaries have thought about requirements for capabilities over time in ways that now require challenge.

Shashank Joshi: There was a really interesting speech. The Chief of Defence Staff in the UK, the head of our armed forces, in this case Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, gives a speech every year at Christmas at the Royal United Services Institute, the think tank in London.

Michael Horowitz: Is there port?

Shashank Joshi: There is wine after the lecture, but we’re not drinking port during the lecture.

Michael Horowitz: But I’m imagining like brandy and cigars and port and like a wood-paneled room.

Shashank Joshi: You’re not far off on the room itself.

Jordan Schneider: Are there oil portraits? Do we have like Hague and stuff?

Shashank Joshi: There are oil portraits. I must declare I’m on the advisory board at RUSI, so I’m very fond of it. But anyway, I’ve gone down this rabbit hole. The reason I brought it up is because I wanted to quote a line from that speech he gave at Christmas where he said:

[W]e have only been able to demonstrate pockets of innovation rather than the wholesale transformation we need.

Where we have got it right is because we used an entirely different set of permissions which elevated speed and embraced risk so that we could help Ukraine.

But when we try to bring this into the mainstream our system tends to suffocate the opportunities.

He then proposed a “duality of systems… Whereby major projects and core capabilities are still delivered in a way that is ‘fail-safe’ – clearly the case for nuclear; but an increasing proportion of projects are delivered under a different system which is ‘safe to fail’”.

Mike, this is pretty much what you told me when we spoke a few weeks ago, right? A willingness to embrace failure — not for your Ohio-class SSBNs or your bombers, but for your smaller systems where the cost of failure is not terrible and you need to fail to innovate. That is so much of what it’s going to take for us to be able to be more Ukrainian in our own systems.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s contrast that with a quote on the US side of the pond from Bill LaPlante, who is the DoD’s top acquisition executive during the Biden administration:

“The Tech Bros are not helping us much… If somebody gives you a really cool liquored-up story about a DIU or OTA, ask them when it’s going into production, ask them how many numbers, ask them unit costs, all those questions, because that’s what matters… Don’t tell me it’s got AI and Quantum in it. I don’t care.”

Michael Horowitz: Bill LaPlante thinks that it’s still 1995. The thing that was remarkable about that quote is even at the time it was so profoundly incorrect in the way that it described the ability to scale emerging capabilities. Shortly before we left office there was a speech or maybe it was from under a question or something where he said that he had learned from the Houthis and what they’d done in the Red Sea that it was possible to produce low-cost munitions. Unclear why what was happening in the US had not triggered that revelation. But he got there.

That is the mindset that requires challenge. If you view the only things worth using as an extremely small number of exquisite platforms, then that takes you down a road where emerging capabilities, even those you can scale, might seem less useful because they might require using force differently — if you’re operating at mass rather than just operating those exquisite capabilities.

The bigger challenge though, is every single major defense acquisition program in the US military is either behind timeline, over budget, or both. Most are both. What that suggests is that the current system, which is designed to buy down risk and produce these great capabilities — and it does, but just slower than it’s supposed to, with higher prices than it’s supposed to — in a way that suggests that the current system is not succeeding.