On April 2nd, we had Liberation Day, a tariff salvo that doubled as a bid to completely reshape the global economic order. Simultaneously, Laura Loomer walked into the White House and fired competent NSC staff who served under Trump 1.0 but apparently weren’t MAGA enough for Loomer and the president. What is going on in the Trump administration, and what does it mean for America's relationship with China and its future place in the world?

To discuss, we interviewed Tanner Greer, author of the Scholar’s Stage blog, who has written a guide for the perplexed. His new report, “Obscurity by Design: Competing Priorities for America's China Policy,” is the product of dozens of interviews and hundreds of hours of studying how key Trump policy-makers think.

We discuss…

Trump's decision-making style and desire for unpredictability,

Why Trump stokes conflict between warring GOP factions, and the policy implications of that approach to leadership,

Laura Loomer and the four quadrants of Trump World geopolitical ideology,

Historical parallels to this administration’s ‘Red vs Expert’ dilemma,

Trump 2.0’s approach to China, and whether Taiwan policy will emerge from the culture war unscathed.

This interview was recorded April 4th. Co-hosting is Nicholas Welch. Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app.

Tariff Uncertainty and Conflict as a Virtue

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with tariffs. How did we get here, and what does this tell us about the Trump administration?

Tanner Greer: This is what I spend the first part of my report discussing — how do we model Trump’s decision-making, and why is it sometimes so difficult to predict what he’s going to do?

There are two main reasons for this. The first is that Trump wants to be unpredictable. By disposition or personality type, he enjoys being impulsive and difficult to deal with. But over the course of his life, and especially his first presidency, he came to realize that the less people know what he’s going to do, the better off he seems to do. Regardless of whether that’s better for the country as a whole, many advantages for him personally accrue from being this unpredictable force — inputs come in, and we don’t know what’s going to come out the other side.

He believes this gives him negotiating leverage. He believes that this makes his strategies more likely to succeed. There’s something self-serving about this, but he has taken this disposition and elevated it to an official philosophy.

Jordan Schneider: In an interview with the Wall Street Journal editorial board before the 2024 election, Trump said there’s no way Xi was going to invade Taiwan on his watch because “Xi knows I’m fucking crazy.”

Tanner Greer: Yes. That was his exact quote. When it comes to Chinese leaders in particular, but world leaders generally, he wants them to think he could do just about anything. A lot of his behavior can be understood as an attempt to make that belief credible. Nixon had the same idea.

This is a key part, in my view, of why Trump does what he does. He actually believes that if he nails himself down by explaining what he’s going to do or how he’s going to do it, then that will work against him and remove his negotiating leverage in the future.

He views international relations as a set of iterated negotiating patterns, as opposed to charting a big long-term strategy of trying to get from A to B accounting for lots of inputs along the way. Instead, he views things iteratively, trying for a better position over time.

Jordan Schneider: We’ve got a lot of competing impulses here. You have these visions that have populated the GOP, where big tariffs need to happen in order to raise revenue, improve negotiating positions, revitalize manufacturing, and decouple us from China. Then you have this iterative game that Trump enjoys playing.

It’s interesting to me that tariffs, which he has clearly prioritized for years, have not had an organized rollout. Even though Trump has been focused on tariffs for a very long time, the implementation appears haphazard compared to, for example, the strategy to squeeze Ivy League universities and law firms.

Tanner Greer: There are essentially two reasons for this. First, as I mentioned, Trump believes that increasing uncertainty about what he will do next is to his strategic advantage. He clearly believes this in the international sphere.

Second, there’s a management style element involved. Trump doesn’t view this as a problem — he sees it as his preferred method of operation. His strong preference is to have a team with conflicting opinions. He wants personal loyalty, but as long as he has that loyalty, he prefers strong personalities who have widely divergent opinions on what should happen and how it should happen.

His management style is to pit these people and factions against each other, then act as the kingmaker who swoops down and chooses the winner of these various discussions. You could think of it as his way of solving the principal-agent problem. How do you keep a bureaucracy in line when it has its own interests? His preferred approach is to pit parts of it against each other.

This style has some advantages. Multiple people I interviewed pointed out that this is very different from how Condoleezza Rice ran the NSC in the lead-up to the Iraq War. Under Rice, there was an attempt to find a consensus position and present it to the president rather than allowing arguments to go directly to the top. If you’re a Republican who wants to avoid repeating the George W. Bush experience, you can understand why Trump’s approach might be attractive.

The weakness here is twofold. First, it’s difficult to implement long-term planning and maintain coherence month-to-month and day-to-day over time. Second, you run the risk of having competing priorities bound up in a single policy because the president isn’t giving top-down direction. Instead, he’s letting things come up to him, and not always making a decisive choice between the various options presented.

The result is multiple people supporting the same policy for conflicting reasons. With tariffs, there are multiple groups with different rationales for what tariffs should be and what they hope to achieve, especially regarding China. I don’t believe the administration has successfully integrated these different views into a coherent policy.

Nicholas Welch: It seems at least plausible that ChatGPT produced their formula for determining reciprocal tariffs. This formula is simple enough, but it’s not how one would normally calculate another country’s tariff rate. Could it be that they settled on this simple formula because of a lack of consensus about what the tariffs were supposed to accomplish?

Tanner Greer: There’s certainly been this idea for a long time — many people have been saying this for months and years — that we need something like reciprocal tariffs because many countries are implementing policies unequally. Additionally, there’s the argument that you need something beyond reciprocal tariffs — something truly measured — because countries will have all kinds of restrictions and their own industrial policies that don’t make the playing field equal.

That’s plausible enough. The question is, if you were given a deadline to calculate the impact of trade policies across the entire world on a bespoke basis — that’s quite hard to do. I don’t have any special insight into the process of creating these tariffs. All I can say is that I’m pretty sure the process happened that week.

Jordan Schneider: During his first term, Trump wrote a note to his staff saying“TRADE is BAD” at a G7 meeting.

Aside from the question of whether ChatGPT came up with the formula, basing it on trade deficits seems to align more with Trump’s thinking than with any of the grand visions of remaking Bretton Woods that we’ve seen emerge from the GOP ferment over the past few years.

Tanner Greer: That’s somewhat correct. However, if you look at these tariffs, they’re actually not that far from what Trump said on the campaign trail he wanted to do. Trump persistently said two things during his campaign. First, he wanted something like 10% tariffs across the board. Second, he wanted something like 60% tariffs on China. He mentioned those two numbers on multiple occasions.

Looking at the current numbers, China effectively has a 60% rate being applied when you combine earlier tariffs with the new ones. For everybody else, you essentially have 10% applied everywhere. On top of that, you have this reciprocal tariff structure that produces really large tariffs in some cases, like with Vietnam, while other countries face much smaller tariffs.

My guess — and this is just an educated guess as I haven’t talked to anyone in the administration recently since they’re all too busy right now —

Jordan Schneider: Lutnick and Bessent, you have an open invitation to come on ChinaTalk to discuss…

Tanner Greer: My guess is that Trump’s logic is something like, “This 10% is going to stick no matter what. And then all those other numbers are maybe negotiating leverage.”

Now, negotiating for what? What are you actually trying to achieve? I think there are multiple answers to that. But I suspect what Trump wants is to have all these world leaders basically come and kowtow, saying, “Okay, what do we need to do to get closer to that 10% and not be at whatever higher percentage?"

For some countries, like Cambodia, I don’t know what they could really do in a trade sense. They could maybe say something like, “We’ll also kick the Chinese out of the Sihanoukville naval base,” if that’s the sort of thing that Trump cares about, if that’s the sort of thing that USTR is willing to consider. But I think they’re probably just in trouble. Whereas a country like Japan has a lot more room for that sort of back-and-forth negotiation.

Jordan Schneider: Trump wants this to be an iterated game, and he wants to have a lot of fun calling folks and cutting deals left and right. But is there a point where people decide they don’t want to play anymore?

At what point, if ever, do countries just say they’re no longer interested in being on America’s team?

Tanner Greer: The question is, is that even possible? If you’re Japan, to take an example here, is it possible not to be on the American ledger, militarily or economically? I don’t know if it really is.

If you’re a country like Vietnam, geopolitically, yes, it is easier to balance away. Economically, it’s much more difficult. If Trump’s calculation is that because we have the consuming power, because our economy is so central to the world economy, many of these countries will have no option but to face the music — in the short term especially, that’s somewhat true.

The question is about alignment in the long term. This could create conditions where lots of countries on the 10-year horizon say, “Maybe we should look towards something more like autarky for ourselves, or maybe we should balance away towards some other option.” I can see that as a realistic response from some countries. But in the short term, I don’t think there’s a “We’re not going to play with the United States anymore” option. In 15-20 years, maybe.

Jordan Schneider: There were some expectations that you could make about America, really post-1945. Trump’s idea that trade is bad and other countries are ripping us off represents a fundamental shift — it’s no longer part of America’s strategic vision that the countries we’re friends with should also succeed economically.

Tanner Greer: I anchored this first part of the discussion by talking about how Trump enjoys and finds strategic value in uncertainty. In my mind, when you look at most foreign countries, what they want from the United States — those who are in our alliance system as well as those who are major trading partners — the vast majority of what they want is actually certainty. They want to know what will happen, at what speed, in what way, so they can prepare.

If you’re a mouse among fighting elephants, you really want to know where the elephant is going to step. Trump believes he has many advantages in not letting anyone know where he’s going to step.

I believe the ability of American allies to accept worse conditions relative to what they’ve been given is actually pretty high. What will be much harder for them is not knowing what conditions they can accept at any point in the future.

If they’re not given some sort of enduring deal that they believe represents the new reality — where they can assess those terms and say, “Okay, this is the new deal, we can do this or we can do things the Chinese way,” and can make that decision — problems will arise.

But if the reality is that the Chinese are very stable in what they want, while the Americans are all over the place — where allies don’t know what America will say, not just administration to administration, but month-to-month, year-to-year — that’s going to be a bigger problem. This will be even more problematic than just not treating allies as treasured partners that share values and other such principles.

This sort of capriciousness or arbitrariness will cause issues in the long term.

Jordan Schneider: Can you come back from something like this? We had big fights in Trump’s first term, and then we had USMCA. If playing these games and having a negotiation is the most fun thing for him, is this just the base case for the next four years?

Tanner Greer: This is an interesting case because we have a lot of data on how Trump ran the last administration — four whole years of how it worked. One interesting question is whether the way things have worked for the last three months is more predictive than how things worked during the previous four years.

There are some discontinuities. Take these tariffs, for example. When Trump announced the China tariffs in the first administration, they were implemented in installments. They started small. Well in advance, it was known that tariffs would be at this level, then this level, then this level, and so on as we applied graduated pressure against the Chinese. It was not “25% tariffs on this country tomorrow."

One question you have to ask is, what’s the difference between the two administrations? Why did the first one have this more measured response, whereas the second one does not? Even when playing the same game, the markets responded much better to the first approach because they had time to plan and prepare.

You could point to a few factors. Robert Lighthizer isn’t here right now. He was an extremely respected individual who had Trump’s ear. He was good at talking to Trump and getting Trump to say what he wanted to do. Lighthizer was very much of the mind that if we’re going to implement a tariff schedule, we’re going to do it above board. It’s going to be completely legally nailed down so the courts don’t challenge us and bring it down. We’re going to go slow and measured, but we’re going to do it.

The corresponding figure on trade policy in this administration seems to be Howard Lutnick. He doesn’t seem to have that same “slow and steady wins the race” sort of personality. This is just my observation as an outsider — I don’t have special insight into how it actually works. But based on what I’ve seen him say and what media reports say, it seems like he wants to push faster than USTR did in the previous administration. If he were to leave, then maybe things would shift somewhere else. I could see that happening.

Jordan Schneider: The whole idea is that you apply a coefficient of poor staff work to all the policymaking. You have both the Trump madman who wants to be on the phone hustling people, and you have poor execution. There’s an exemption for semiconductors, but it applies to CPUs instead of GPUs.

Clearly they wanted to have some carve-out for AI, but they just did it wrong with last-minute staff work. You’re blowing up Madagascar’s economy, and it’s not like America is going to be growing vanilla beans in the US anytime soon to compensate. If you’re going to let Laura Loomer fire people, are you going to get better staff and better execution? Probably not.

Tanner Greer: I’m sympathetic to the argument that what they want to do doesn’t matter if they can’t do it well, especially when trying to rejigger the global trading economy.

In preparation for this discussion, I reread something by Stephen Miran, who’s the Council of Economic Advisors chair for the Trump administration. He wrote a big 40-page paper in December with all kinds of academic citations about how we should use trade as leverage to redo the existing financial trade order to be more favorable to American manufacturers and more sustainable for American budgets.

It’s a pretty smart and interesting approach. What struck me in reading it now is how he talks a lot about being cautious and careful when implementing these changes. He emphasizes the need to be slow and graduated, “just like we were during Trump’s first term.” He says it repeatedly: “Just like we were during Trump 1.0. We need to do it that way, just with more ambition.”

Obviously, not everybody has his same agenda, and he’s not in a decision-making authority. That’s a consultative body that he runs. But it does point to the weaknesses of some of these approaches. If this was done in a measured way, I wonder if the responses would be the same throughout the commentariat. I suspect many people would be just as upset no matter what. But the markets would probably respond differently. I don’t think you’d have the big market run today if there was a slower, more measured, more carefully articulated version of what’s happening.

Jordan Schneider: I find it interesting how Trump, JD, and many others frame their economic and geopolitical actions as responses to a clock that’s almost run out. They argue we need to act boldly and quickly now. Otherwise, America’s fiscal health will be ruined, and America’s ability to exert influence globally will become a wasting asset that we need to use while we still have the chance. Thoughts on that, Tanner?

Tanner Greer: You can examine this at different levels of analysis. At the individual level, my report emphasizes that historically, the Trump administration has cycled through people quickly. What constitutes policy today may not be policy tomorrow as personnel changes occur.

This incentivizes individuals with a program to implement it as soon as possible and to do so in ways that make it difficult to reverse. This explains the preference for drastic actions. Consider the proposal to eliminate US aid on questionable legal grounds — the goal is to ensure that when people with different opinions arrive later, or when Congress mobilizes, the situation becomes irreversible. The tariffs approach follows a similar pattern.

Another perspective focuses on Trump personally. This is his final administration, his last opportunity. Despite speculation about a third term, his rapid pace suggests he doesn’t see it that way. He wants to make changes with visible impacts soon.

Furthermore, if you’re committed to transforming the global trade order, the global political system, or the federal government’s operational structure, many fear that proceeding slowly only provides ammunition to opponents and activates potential veto points. You need to move before that resistance mobilizes.

This probably reflects a direct lesson from the first administration, where many initiatives were frustrated — sometimes for valid reasons, often for completely irrational ones. Things were consistently delayed and obstructed, which has led Trump and his circle to conclude, “We can’t repeat the first term. We must take action immediately, regardless of staff preparation."

The priority becomes implementing significant directional changes rather than appearing methodical but never achieving results. Moving slowly creates enough opportunity for veto points, bureaucracy, and Congress to respond.

This aligns with Trump’s overall philosophy: “I operate best when people can’t predict my actions. If I act first and everyone else must react,” that’s his preferred approach. Proceeding deliberately forces you to respond to others as much as they respond to you.

Jordan Schneider: There was this concept of the “Trump put” during the first administration — the idea that if the market dropped enough, Trump would stop making unpredictable decisions. That safety mechanism seems mostly gone now. This is our first real test, I suppose. The psychological shift manifested in this particular behavior is a fascinating development.

Tanner Greer: The safety mechanism is mostly gone, although much depends on market performance over the next six months. Trump genuinely believes there will be a period of problems, but not permanently. If we experience a two-year recession, he would likely reconsider his approach.

Jordan Schneider: Assuming he would reconsider is one of the key assumptions I’m questioning.

Tanner Greer: I’m not predicting which direction that reconsideration would take. One consistent truth about Trump in power is that he’s constantly reassessing. He doesn’t maintain loyalty to ideas or people. He adheres to certain broad principles — negative views on immigration and trade — but demonstrates remarkable flexibility in his persona, and his base allows him considerable leeway in his actions.

The expectation that his current approach will remain unchanged two years from now is almost certainly incorrect. The uncertainty for everyone else is which direction he will take, as there are many possible paths.

Jordan Schneider: I see a potential scenario where Trump becomes like King Lear at 10% approval in 2027, essentially wanting to “burn the whole world down.” We shouldn’t entirely discount this possibility.

Tanner Greer: That’s not what concerns me most. The issue with Trump at 10% approval in 2027 wouldn’t be his desire to destroy everything but rather his fear that if a Republican doesn’t win the subsequent election, he might face legal consequences. That would be his primary concern.

The difference between Hitler and Trump is that Hitler was deeply ideological. Trump himself isn’t that person. It doesn’t align with anything I understand about his character. He likely believes he’s “God’s gift to humanity” in some sense, that divine protection saved him. But I don’t think he sees himself as “the embodiment of an abstract ideology that people weren’t ready to receive yet, weren’t prepared to purify themselves for in the grand struggle.” That’s not Trump’s self-perception at all.

MAGA’s Economic Factions

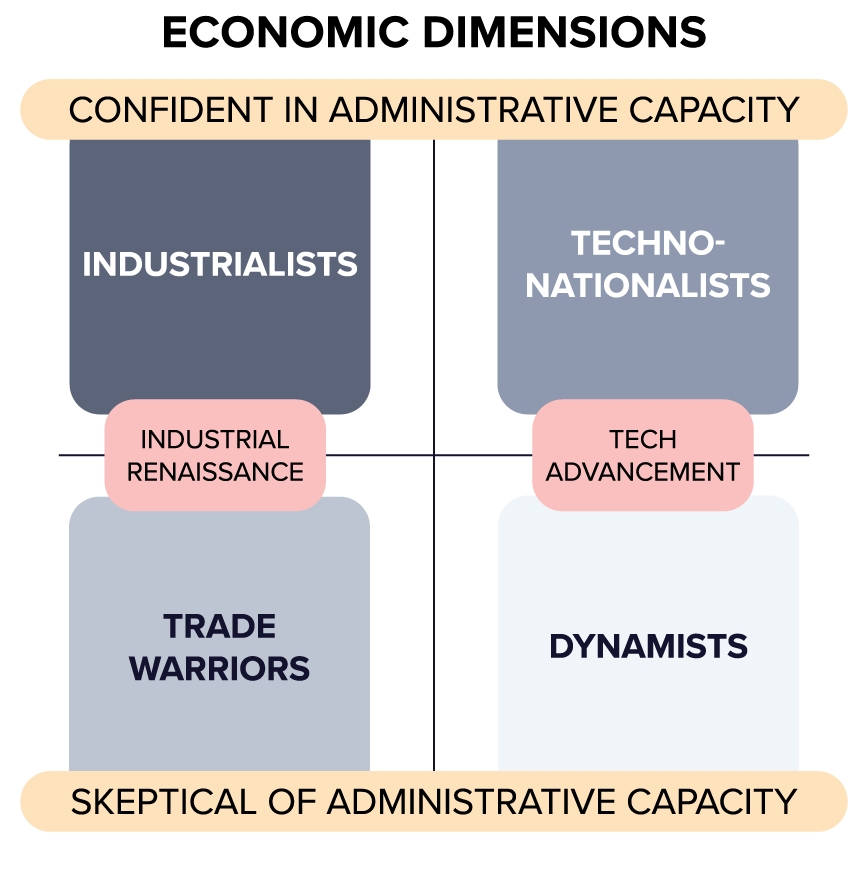

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss what people in Trump World actually believe. Let’s focus on the economic dimension. In your framework, you chart Trump World economic thinking along two axes — one focused on industrial renaissance versus emerging technology advancement, and another that considers whether the administrative state can be effective or is inherently weak and ineffective as a tool for change. Tanner, could you explain this quadrant of thinking? Perhaps assign some key figures to better illustrate the four corners for us.

Tanner Greer: There are certain economic views where every MAGA supporter has some consensus. Especially regarding the economic vision concerning China, they focus on winning the economic competition with China.

What does winning mean? It usually involves some sense of independence. There’s a widespread belief that the United States is too dependent on the world abroad and thus not free. To use Trump’s word from earlier this week, America is not “liberated.” He stated that this will be a new Independence Day declaration. The idea is that international ties mostly constrain us, making us dependent on other countries for basic goods and national security essentials.

The vision is a world where American strength and wealth don’t depend on the goodwill of foreign countries, but rather the reverse — where foreign countries’ prosperity and security depend on our goodwill. That’s the unifying vision.

Jordan Schneider: This is essentially an autarkic dream, right?

Tanner Greer: I don’t think it’s necessarily autarkic. It can be, but the fundamental question is who depends on whose good graces. Consider America in 1946, when the entire world’s economy had trade relations with us because basically the whole world was buying our products. I don’t think any Trump supporter looks at America from 1946 to 1955 economically and says, “That was terrible.” In some ways, they look at that period and say, “That’s great."

If we could recreate that world where America is the world’s factory and everyone buys from us — where they can’t cut us off, but we can cut them off — they’d be completely fine with that. The question becomes, what level of self-sufficiency is needed in a world where other countries are wealthier? What production do we need to replicate domestically? What can we source from abroad?

Generally speaking, all quadrants agree that globalization reduces America’s field of action. This is particularly dangerous because globalization has mostly benefited China. It would be one thing if we were ceding capability to Japan or the EU, which many view as problematic. It’s even worse when it goes to China, which has been the predominant story — China has gained many capabilities that America now depends on.

Having a geopolitical rival upon which you are economically dependent creates a problem in their mind. Are there some 1930s parallels? Yes, to some extent. But I don’t think the vision is complete autarky.

Nicholas Welch: In each of the four quadrants you’ve identified for economic policy makers in Trump’s orbit, what is the limiting principle? For instance, dynamists in the lower right quadrant — people who are skeptical of the administrative state’s capacity and want a tech revolution — might say, “We need to reshore manufacturing of critical national security items like chips.” People on the other side of the spectrum might argue, “We need to reshore tons of manufacturing capabilities."

Where does each camp draw the line as to what we need to bring back to America? Is the question whether we need to reshore T-shirts for American national security as well? Where does each camp set boundaries?

Tanner Greer: That’s an excellent question for understanding the divides between camps, especially regarding my first axis that separates the groups. This axis distinguishes between those who view winning the future, securing American national security, and taking control of the commanding heights of the 21st century economy in terms of developing new technologies versus those who want a much wider industrial renaissance.

You can think of it as a spectrum with extremes on each end. At one extreme is the person who believes the only thing that matters is AI — nothing else is significant, and if America wins the AI race, everything else falls into place. They believe nothing needs to happen for AI development except ensuring companies like OpenAI or Anthropic have the necessary funding and energy resources.

At the opposite extreme, you have someone arguing, “We need everything, including T-shirts.” In reality, most people aren’t at either extreme, but that’s the spectrum.

People on the right half of my quadrants — the leading tech side — typically come from national security backgrounds or tech investment backgrounds, sometimes finance as well. Let’s start with the bottom right corner, the dynamists. A prominent example outside the administration would be Marc Andreessen. Many people from his circle have joined the administration, and you can see their influence.

These dynamists look at American success over the last 30-40 years and argue that we need to replicate those successes. A chart that went viral on tech Twitter a few months ago showed the productivity gap between the United States and Europe.

In 2000, people thought the EU might reach the American level, but it hasn’t. The dynamists’ explanation is that America had the most important firms and the most significant technological advancements during that period, from Apple, Meta, Amazon, and Silicon Valley.

They often think in terms of firms. They want to ensure we have the winning companies for the future that will implement the next round of technological revolution. If those firms are Chinese, the productivity gap you see between the EU and United States will exist between China and the United States. We need to make sure our firms lead the way.

The rest of the story doesn’t matter to them. It doesn’t matter if we manufacture T-shirts. It probably doesn’t even matter if we produce steel — we can import that from other countries. What matters is that the firms capturing the largest percentage of global growth in the future, those at the forefront of new technologies, are American.

When looking at which suite of technologies will matter, they prioritize AI, semiconductors (especially if China might cut us off in the future), quantum computing, automated systems, robotics, UAVs, new energy technologies, aeronautics, and space. That’s the realm in which these dynamists think.

The group in my top right quadrant, whom I call the techno-nationalists, have a similar perspective but are even more national security oriented. Their argument is less about “We need to have the firms that generate the most economic growth” and more about “We need to possess the technologies that will have military applications in the future, and we must ensure we’re directing national resources toward that goal."

Nicholas Welch: On the two left quadrants, the people who favor an industrial renaissance, you write in your report that people in those camps see Silicon Valley not as a model of productivity success but as a cautionary tale.

Tanner Greer: There’s a national security-oriented way they view Silicon Valley, and there’s a more economic and political perspective. Let’s start with the latter.

Trumpism, in some ways, began because certain parts of the country felt left behind by the fantastic economic growth that occurred between 1990 and 2015. If you live in West Virginia, Buffalo, New York, or Winesburg, Ohio, the vast increases in American productivity and lower consumer prices haven’t been sufficient to offset what you’ve lost through deindustrialization.

As a practical political matter, these advocates point out that if we don’t have an economy that meets the needs of people who live in these swing states — who have been at the core of our movement from the beginning — then we’re doing something fundamentally wrong. This failure will create even worse populist eruptions in the future if we can’t address these needs.

There’s also an economic argument. Many of these proponents look at China and challenge a previous assumption: the idea that American companies could handle design while exporting the middle-tier, hard-tier construction to countries like China. The theory was that America would still lead in design and software — the user-end experience and the design experience — while all the middle manufacturing could go to China or other industrializing countries, making products cheaper without compromising our leading edge.

Many people studying the Chinese economy now — reflected in publications like American Affairs or American Compass — argue this assumption is fundamentally flawed. They contend that if you excel at production, you soon develop the skills needed not only to produce but also to design, engineer, and develop the backends. That’s precisely what’s happening in China right now.

Their argument is that if we follow the Silicon Valley model where Apple focuses on user experience and design but exports hardware manufacturing to foreign countries for cost savings, we’ll end up with companies like Huawei and Xiaomi leapfrogging America in developing new technologies because they’ve cultivated both design and engineering expertise. Electric vehicles exemplify this dynamic.

Jordan Schneider: That’s how we go from the VEC saying we should impose heavy tariffs on China but allow friendshoring, to the position that we also need 50% tariffs on Vietnam. The argument being those factories should be in America, not in other countries that don’t even support us anyway.

Tanner Greer: It depends on the particular product. Countries like Cambodia or Vietnam often produce T-shirts, which presents the hardest case for these advocates to make. But when discussing major industrial sectors like electronics or steel, they argue you need what they call a “functioning industrial ecosystem” — overlapping companies, integrated supply lines, and engineers within your country who will develop new technologies.

They add a national security dimension: if war breaks out, especially with China, it’s dangerous not to produce even basic materials like steel and aluminum domestically. Production facilities located far away can be targeted during conflict. If these materials are produced in China itself, we would lose access entirely during tensions. We need this capacity at home.

That summarizes the perspective of those on the left side of the framework: we need much more manufacturing here in America. Otherwise, we’ll face negative consequences in developing new technology, meeting the political and economic needs of average people across the country, and safeguarding our national security.

Nicholas Welch: Let’s say you’re an old-school Republican who still really likes the ideas of free markets, tax cuts, and deregulation. If you want to be influential to Trump, which camp would you most likely affiliate with to try to be in his orbit?

Tanner Greer: If you’re an old-school free marketer, you’d probably find the easiest affiliation with the bottom-right corner, what I call the decentralists. As a reminder, the top and bottom of the graph represent people who believe government should be used for conservative ends versus those who are deeply skeptical that government can be used effectively.

People in the bottom-right believe in a new technology paradigm and also believe that government mostly needs to get out of the way. Their program centers on generating economic growth and developing new technologies by eliminating regulations. This aligns with the “abundance agenda” and NEPA reform that many of these people advocate.

This perspective certainly aligns with what the “DOGE people” think and have been implementing — that the core problems are inefficient bureaucrats, DEI initiatives holding down the economy and foreign companies, and outdated 1970s environmental regulations. They argue we would already have nuclear power plants everywhere without these obstacles.

A free-market advocate can work with this group relatively easily. However, in terms of personalities, there might be clashes since many of these individuals come from tech backgrounds and don’t think or talk in traditional conservative ways. In terms of actual policy vision, this is where someone like Vivek Ramaswamy positions himself. He supports tariffs, but only for reshoring key national security assets. Otherwise, his goal is to remove government from the economy.

Nicholas Welch: Are we looking at a post-free markets America for the foreseeable future, or will there be a swing back?

Tanner Greer: There will probably be a swing back eventually, especially if we experience something like a Great Depression-style economic downturn. Often, free-market swings are reactions to previous approaches. Economic liberalism typically seems less outdated to people once it hasn’t been tried for a while.

In Trump World, there’s no coherent answer to this question, partially because of the diverse positions within the administration. On the top half of my framework are people who believe Republicans have been wrong since Reagan’s time, and that we need much more serious intervention in the economy to build the future.

There are generally two precedents cited for this interventionist approach. People in the top-right corner — the national security hawkish folks or techno-nationalists — frequently look back at Cold War-style economic interventions designed to create new technologies. Many technologies resulted from the marriage of government and private sector for national security needs. They argue, “If it worked for us in 1950, why won’t it work now?"

People in the top-left corner also believe in government intervention. I call them industrialists or industrial policyists because they strongly advocate for comprehensive industrial policy. Oren Cass is perhaps a leading figure in this camp. J.D. Vance and Marco Rubio are certainly in this group as well. They would like to see the full suite of policy tools used not just to advance American technology, but also to build American factories and create a more equitable — though they won’t use that word — distribution of economic benefits across the United States.

This top-left industrial policy camp, in my assessment at this point in the administration, isn’t securing many significant wins. They have intellectual victories and support tariffs, so if you consider tariffs a win for them, they’ve achieved something. But there’s little appetite in the administration thus far for the kind of spending these advocates envision. That’s perhaps the weakness of their approach — implementing robust industrial policy is difficult without raising taxes or increasing the deficit, both of which Republicans are very allergic to.

Let me address the bottom-left camp as well — the trade warriors — because there’s something non-obvious about their position. Many people attracted to tariffs are often critics of broader industrial policy. They disliked the CHIPS Act, for example. They are critics of the administrative state and don’t believe government can implement industrial policy effectively. Yet, they nevertheless believe tariffs might work.

This seems contradictory but isn’t necessarily so. Tariffs, though high-impact, are low-bureaucracy. The USTR has only about 200 people. They might need to add another 100 people to negotiate with every country in the world, but that’s still minimal. If you want an industrial policy that could operate with a night-watchman state — the kind of state America had in the 19th century — tariffs were precisely how America did it back then. If you want to pursue the “Doge thing” of dismantling the federal government without losing the ability to foster an industrial renaissance, you’re often very attracted to the tariff position.

Red vs Expert: Loyalty vs. Competence

Jordan Schneider: Tanner, a challenge for you — can you use Laura Loomer as a hinge to explain Trump World’s geopolitical camps?

Tanner Greer: Do we need any background for people who don’t know what happened with Laura Loomer? Maybe you should introduce it first. Not everyone will have seen that piece of news amid all the tariff coverage.

Jordan Schneider: I don’t know if I can properly introduce Laura Loomer, but I’ll try. Actually, why don’t you explain her in four sentences? I feel like you have a better understanding of her perspective.

Tanner Greer: Laura Loomer is a media personality and activist on the MAGA right. She was influential during the election and remained a constant ally of Trump throughout the primaries. One of her main focuses has been policing Trump World to ensure that “RINOs” (Republicans In Name Only) do not receive important administrative posts in this administration. Her theory is that much of what Trump wanted to accomplish in his previous term didn’t happen because he had people working against his agenda.

I dispute this theory, but we can discuss that shortly. The key development is that she recently came to the White House with a dossier containing evidence that certain individuals were “Never Trumpers” at some point and allegedly disloyal to Trump’s current program, suggesting they should be dismissed. It appears Trump removed several of them based on her information.

By my count, three people in the National Security Council were let go. This morning, news broke that both the head of the National Security Agency and the deputy director were also dismissed, presumably because of whatever Loomer presented in her dossier. However, not everyone she targeted has been removed. People like Alex Wong or Ivan Kapanadze on the NSC, whom she has frequently criticized publicly, still retain their positions. In essence, she provided a briefing, and subsequently, people were fired.

Nicholas Welch: Try as she might, Laura Loomer will have a very difficult time firing Vice President JD Vance, who was once a Never Trumper. Good luck to her.

Jordan Schneider: She’s also a member of the tribe and has a huge bone to pick with Elon, particularly for his China connections. This is interesting because it’s not really something that’s come up much in discussions.

Tanner Greer: She’s not the only one from that faction. Steven Bannon has also gone on the warpath against Elon for months for very similar reasons.

There are two ways to view what happened. You can see it as crazy that far-right internet personalities are firing people in the National Security Council, which obviously won’t lead to good policy. Alternatively, you can view this as a fight within the Trump administration itself between different factions, and I suspect the second interpretation is correct.

Loomer is likely as much an agent of certain forces inside the administration as she is an outside influence. This provides a way for people who dislike certain policies to bring issues to Trump’s attention without appearing self-serving. I don’t know if that’s true, but if it is, it’s very clever.

It wouldn’t surprise me to find out that people in the administration helped orchestrate this whole situation. How else would Loomer learn all these details about what David Feith thinks? She’s not part of that sphere, but there are people who are and who know Laura Loomer. That’s my guess about how this actually happened.

Nicholas Welch: It’s a hit job. We’ve got people paying Libs of TikTok and other influencers to dig up dirt. It’s like an internal cancel culture.

Tanner Greer: This isn’t new or unusual in the long history of American politics. It’s not that different from leaking something to the New York Times to discredit somebody internally. The difference is Trump doesn’t care about what the New York Times thinks, whereas he will give an audience to Laura Loomer. The dynamics are not that different.

Jordan Schneider: And he makes JD Vance and other cabinet officials sit there while she berates them, which adds another level of wildness to the situation.

Tanner Greer: But did JD Vance mind? He’s on the opposite side of these debates from the people who were released. In some ways, this benefits JD Vance, assuming he actually cares about his political program, which I believe he does.

Unlike Trump, Vance is more of a true ideological believer. He’s enough of an ideologue to actually believe in ideas as such.

Nicholas Welch: For sure. There was this quote from Time Magazine. Vance had an interview there back in 2021. Vance told Time, “Trump is the leader of this movement, and if I actually care about these people and the things I say I care about, I just need to suck it up and support him.” That’s 2021 Vance. This appears very consistent with how he is now. He does have a definite ideological vision.

Tanner Greer: Two consistent themes with Vance during this time are evident. First, he views his job as vice president to be the prime public defender of Trump, period. This is similar to how Nixon was with Eisenhower — the idea being that Eisenhower could stay above the fray while Nixon would handle all the difficult matters. Trump doesn’t necessarily want to stay above the fray all the time, but the dynamic is very similar.

Second, when it comes to personnel or influencing policy that is one level below Trump’s direct involvement, you can see Vance’s concerns manifest. He definitely has a project.

Jordan Schneider: The quality of staff work cannot be dismissed. There is not a deep bench for this expertise. If you want to press a button as a president and have it create a certain outcome, you need people to cross I’s and dot T’s. The more this happens, the more you have to resort to increasingly junior people who simply won’t know how to fly the plane.

Tanner Greer: This is a real concern and a real problem. The Trump administration has what might be called a “Red and Experts” problem. I’m writing an essay about this that you’ll eventually see, titled “Red and Experts."

Let me give you a non-totalitarian example of this concept. “Red and Experts” is a phrase used in communist systems, especially in China — hong yozhuan — to describe the kind of people Mao wanted running his systems. Communists come into power and face a problem: the median person in the bureaucracy belongs to the bourgeois class they’re trying to overthrow. They strongly believe that the preferences of people from this class are orthogonal to the program they want to implement.

So what do you do? Do you put these “bad class element” experts in charge, or do you appoint ideological believers (“reds”) who don’t know what they’re doing? Ideally, you find people who are both red and expert, but otherwise, you must triangulate this problem. This has been a consistent challenge throughout human history whenever one group takes over.

A compelling example of this occurred when Republicans first came to power in 1860. When Republicans took control of Congress and the executive branch, it was after Democrats had controlled it for a very long time. Most of the military consisted of Democrats. Half of the military seceded to the South. Most of the remaining military voted Democrat.

Republican after Republican in Congress dragged generals through hearings and constantly protested to Lincoln, saying, “The reason we’re not winning this Civil War is because we aren’t putting in power people who believe in the program. We keep appointing people who are sympathetic to the South, who like their old Southern comrades they’re fighting against, who don’t want to abolish slavery. If we put our people in power, they would fight the war much harder and do the tough things that need to be done."

Lincoln tried this approach in a few cases — John C. Frémont, for example — but they didn’t perform well. Ironically, the generals who performed best for the Union were often people like Sherman, who before the war didn’t want it to happen. Sherman was teaching in the South at the time and, after his first meeting with Lincoln, thought, “This guy’s an idiot.” As Sherman notes in his memoir, “I hated him when I first met him. I thought he was an idiot. It was his fault this war was happening."

But Sherman liked to fight. Grant liked to fight. They were very good at fighting. If you could get out of their way and let them do their job — killing people and burning things — you could achieve success. Looking at the class of generals and admirals who won the war — Farragut, Meade, and Sheridan (who was very Republican) — as a whole, it’s not an extremely ideological group. What mattered was their competence.

The problem in the U.S. Army in 1860 was that there were many incompetent generals who hadn’t fought in a war. If the Republicans today were saying, “The problem is we have too many incompetent people who haven’t experienced the pressure of wartime to rise to the top. What we need is to find competent people who will do what we tell them and do it well because they’re American” — if they cared more about that instead of loyalty tests — they would likely perform better. The general lesson of this “red and experts” problem is that you only succeed when you learn to have reds who can effectively manage experts.

Jordan Schneider: We do have a two-hour Civil War history show coming out soon, I promise. The dynamic that Tanner is talking about is written up beautifully by Bruce Catton in his book “Glory Road.” It’s part two of a trilogy about the Army of the Potomac.

When I was reading that, it felt very much like Stalin in the 1930s — there are snakes in the grass who aren’t supporting the program. We can reference Hitler again: “My generals are betraying me. They launched Operation Valkyrie, so of course they were always against me from the beginning.” This whole notion of “I am losing because I don’t have loyal people executing my vision” is a great psychological excuse for failing in other dimensions.

In reality, there are many human endeavors where you actually need the person with the PhD or the person with 15 years of experience, rather than someone with the right ideological orientation.

Tanner Greer: I don’t want to diminish this concern. People can make a good argument that in 1860, George McClellan prosecuted the war with less ferocity than he should have because he was sympathetic to the South. This argument might be true.

Throughout human history, there are numerous examples of disloyal bureaucrats subverting a program. However, in my mind, this isn’t an argument for replacing everyone in the bureaucracy with loyalists. It’s more of an argument for finding people who are skilled at getting bureaucracies to do what you want.

Don Rumsfeld had a Pentagon full of people who didn’t agree with his program, but he was very good at getting them to do what he wanted. That’s the quality you should be selecting for. They probably underestimate the number of people who, while not necessarily Trump voters, will simply do what they need to do because they believe in following government directives. There are actually many people like that.

Jordan Schneider: But here’s the thing, and this comes back to the beginning of our conversation, Tanner — if we don’t actually have a clear vision, if the vision is simply “I am Trump, I like negotiating, I like keeping my cards close to my chest,” then the people who aren’t comfortable with “let’s just defer to this guy” present a problem. It’s hard to point a Donald Rumsfeld in a particular direction because that direction might change completely two months from now.

Tanner Greer: That’s fair, although the problem with Don Rumsfeld too is that in some ways he had his own vision that wasn’t matching up with Bush’s. At the top level, I’m more sympathetic to Trump’s position. He feels that various National Security Council principals — at the level of Rubio, Waltz, or Hesgett — are pursuing agendas that contradict what he wants to do, similar to his experience with Mattis.

I have sympathy for him saying, “I need people in my decision-making council to at least not be pursuing their own programs, but bringing the decisions up to me.” I’m not sure that’s what happened here with this Laura Loomer situation. I’ve seen no evidence that David Feith was pursuing his own agenda. I think it was more of a pure loyalty test where, at some point between 2020 and now, he must have said something that sounded anti-Trump, and now he’s being cut off.

Jordan Schneider: He doesn’t get the JD grace.

Tanner Greer: That’s right.

Taiwan and the MAGA Geopolitical Compass

Jordan Schneider: Let’s get back to our geopolitical quadrants. We have one axis that represents optimism versus pessimism for American power and capability. The other axis represents power-based viewpoints versus value-based viewpoints of how America should think about and interact with the world.

Tanner Greer: The first and most important of these axes is how you feel about American power. Do you feel confident that America is strong, that its potential is under-utilized or unrealized at the moment? Or do you think that America is basically in trouble — culturally, fiscally, politically, militarily — unable to do what it once was able to do?

This distinction matters, especially when it comes to China, because it impacts what kind of posture America can afford to take. If you think America is fundamentally weak, you believe the range of possible outcomes with China is much more constrained, and the best case is something like détente or a balance of power. Preventing China from invading Taiwan becomes the best we can do — and maybe much less than that.

On the flip side, if you believe that America is fundamentally strong, you are often much more willing to consider maximalist solutions with China. You might believe we can achieve victory against China or force them into some sort of Cold War collapse. You’re also much more likely to think there aren’t trade-offs between China as a problem and other global hotspots. We don’t necessarily have to withdraw completely from Ukraine to focus on Taiwan because we have the potential resources to address both challenges. We just aren’t using them smartly enough, or our defense budget is insufficient. The defense budget isn’t a law of the universe — it could be changed. What Trump wants will happen, so let’s convince him to increase our defense budgets.

That’s one axis. The second axis is whether you analyze American foreign policy primarily through the lens of realpolitik hard power, or if you believe there are other values-based considerations that matter.

The top half of my diagram represents the realpolitik adherents. They’re straightforward to understand and follow a relatively simple model. They believe force is the most important factor in international relations, and what matters is whether America has it, and whether alliances contribute to or detract from American power. The people in the bottom quadrants are quite different.

Nicholas Welch: The two different camps of values-based perspectives actually differ in the kinds of values they’re assessing. Can you describe how those two camps differ?

Tanner Greer: Yes, that’s right. They’re less parallel than the top ones. For the top quadrants, if your calculation of American power changed, you would simply move from one camp to the other. But for the bottom people, they share a similar way of thinking about the world, which is that the international order has a feedback relationship with domestic values and order.

Just as domestic statecraft should be informed by a positive vision of what we want to achieve — a vision of the good — they believe the same applies to the international sphere. People at the top disagree, arguing that only power matters and everything else is a distraction or contradicts the different logic that operates internationally. The people in the bottom two quadrants reject this view.

The people in the bottom-left corner, whom I label “crusaders,” believe you need to forcefully defend abstract ideals like democracy and liberty on the international stage. By defending them globally, you’re reinforcing them at home, and they view China as threatening these values domestically. They often focus on influence operations as the primary problem China poses for the United States.

They also have the reverse perspective. One paramount example would be someone like Miles Yu, who strongly believes that democracy and human rights aren’t just good ideas but potential weapons to use against the Chinese Communist Party. Where the communists say, “All these things are meant to undermine us. All these ideas and the international order are eroding our internal regime,” someone like Miles Yu would say, “That’s great. Let’s do it consciously instead of unconsciously.”

Nicholas Welch: In your preview of this report back in October, you called this quadrant “restrainers.” Now you call them “culture warriors.” Can you describe what the restrainer/culture warrior people think?

Tanner Greer: I don’t call them restrainers anymore because I realized this term was getting confused too much. “Restrainers” represent a long academic tradition of people arguing, “The United States needs to come home for strategic reasons. We need to be more isolationist. It would be better for the whole world if we were that way.” Many people in the culture warrior camp think that, but they arrive there through different logic.

Their main concern is winning the culture war. Their main concern is recreating the American economy, politics, and culture along grounds they find less hostile to their worldview. They have numerous internal divisions about what those specifics are. The main point is that they don’t like the standard progressive liberal orthodoxy that inhabits most of the American bureaucracy, academia, NGOs, and much of the corporate world.

These individuals tend to view the liberal international order as an extension of the same progressive order at home that they’re fighting against. They view it that way in two respects. First, they see the national security bureaucracies that maintain this order as strongholds of the worldview they oppose — CIA, FBI, even the military officer corps, full of progressives. Second, they believe there’s a feedback relationship, where maintaining the international order reinforces a set of values that is then weaponized against them domestically.

Therefore, they see no reason to sacrifice American dollars and American blood to uphold a system that they believe is trying to eliminate their cultural commitments. That’s their basic belief.

You could add a third element: traditionally, Republicans are elected, they believe, to roll back certain social and cultural conditions. This never happens because Republicans always concentrate on foreign affairs. They argue we need to reduce focus on foreign affairs so that domestic cultural issues can take precedence. That’s the logic of these folks.

Jordan Schneider: Tanner, why don’t you connect this quadrant to caring about defending Taiwan?

Tanner Greer: What does Taiwan mean to these four quadrants? For the last few years, the Taiwanese have emphasized, “We are a democracy. We’re a liberal democracy in Asia.” They’ve often said things like, “We’re the only liberal democracy in Asia that has legalized gay marriage.” This is not only unconvincing to these people, it’s an anti-signal — an argument against Taiwan’s defense.

Many of these individuals would not be willing to defend Taiwan for the sake of values they don’t necessarily hold. They often view competition with China as a problem only insofar as China has a hostile relationship with the United States because we need to address necessary trade issues. They want a military guarantee so they can pursue aggressive trade policies without China escalating to military options.

Otherwise, they don’t believe the United States has a vested interest in fighting a war with China, especially over Taiwan. Some might acknowledge broader questions about China’s power over us and the importance of maintaining American independence. However, they don’t necessarily see defending allies worldwide as the best route to protecting American independence.

Instead, they often view such defense commitments as excuses the national security state uses to increase its own power within the political coalition and strengthen its position in American society.

Nicholas Welch: Can we apply the Taiwan policy framework to the remaining three quadrants? We’ve covered the “prioritizers” who are skeptical of American power but have power-based viewpoints. Can you highlight the difference between a “primacist” (someone who’s power-based and optimistic) versus a “crusader” (someone who is optimistic but values-based)? Primacists aren’t going to say they don’t care about democracy at all. Being American, they’ll probably say things that sometimes sound like crusaders, even if it’s not as explicit as someone like Miles Yu.

Tanner Greer: The restrainer types do care about democracy as majoritarianism for America. They care about freedom of speech in America. They often view national security matters as harmful to those American values.

Someone like Senator Mike Lee, a prominent figure in this world, constantly talks about how democracy and liberties are being sacrificed for an unnecessary foreign policy. Or Russ Vought, who now heads OMB, makes essentially the same argument that our focus on foreign policy has come directly at the expense of domestic priorities.

Prioritizers are also skeptical of American capability and power. They’re somewhat pessimistic about America’s future, and this affects their views on Taiwan and China. Their standard position appears to be encoded in their stronghold at the moment — the Office of Secretary of Defense at the Pentagon. Many of these individuals have been placed there, and there was a recent Washington Post report about a new memo stating that Taiwan must be the organizing contingency for the entire United States military.

That’s not a restrainer or culture warrior approach to the problem. The prioritizers’ view is that they care about similar issues as culture warriors, but they think those individuals are too blasé about what happens if China becomes the global superpower. They believe Taiwan is the only place where China can be stopped from becoming a global superpower. Therefore, everything else needs to be deprioritized to focus on this challenge. They argue we must exit Ukraine, leave the Middle East, and concentrate all resources on Taiwan because America is in such a weak position that unless we do that, there’s no chance of victory or deterrence.

Jordan Schneider: In your paper, you connect domestic success on culture war issues like DEI to America’s ability to project power globally and win wars. Could you expand on that for us?

Tanner Greer: Think of it this way — the primary difference between the various camps and their policy approaches is how strong they think America is. What factors contribute to this assessment? This will vary from person to person. Some factors are obvious, like comparing the number of ships we have versus the number they have. Other factors are more intangible.

Much of the pessimism on the Trump side stems from their belief that America needs to be made great again because it currently isn’t. They believe America is culturally falling apart, becoming progressive, and experiencing cultural disintegration where people don’t feel loyalty. Citizens won’t sign up to fight for the military. There’s no longer a martial spirit inside the military nor cultural coherence outside of it. They believe we can’t get the bureaucracy to do what we need, so if there is a contest with China, we’ll be fighting against ourselves the entire time.

These perceptions factor into calculations about whether America is strong enough to deter a war with China or accomplish other objectives. This connection is important and very underemphasized.

I recommend people read an essay written by Michael Anton in 2021 for The Federalist, entitled, “Why It’s Clearly Not In America’s Interest To Go To War Over Taiwan.” Michael Anton is now heading policy at the State Department. In the essay, he lists reasons why we shouldn’t defend Taiwan, most related to America’s lack of strength.

When explaining why he believes America isn’t strong, he mentions the typical concerns about shipbuilding numbers but then adds points about pride flags and transgender troops. He presents a whole list of cultural issues that most foreign policy analysts, both domestic and international, view as separate from foreign policy. For much of Trump’s inner circle, that separation simply doesn’t exist.

Jordan Schneider: This is where I see the Nero decree energy coming back. If progressive policies appear to be winning in 2027, then I imagine the Taiwan commitment will become less clear. Wouldn’t you agree?

Tanner Greer: Yes, I would agree. There will be more forces for restraint in a world where Trump’s people feel that all their initiatives — DOGE, tariffs, remaking the global order — have failed. Perhaps there’s an argument that they might look for a war to appear strong and gain more trust than Democrats. That’s a possibility, but my intuition tells me differently.

If, after two or three years of Trump in power, America appears to be in a worse position culturally, economically, and politically than when he took office, this will translate into a larger percentage of people around Trump feeling America is incapable of standing up to China. They might believe America needs to compromise and regain strength before confronting China — essentially adopting a “hide and bide” approach.

Jordan Schneider: You note in your paper, Tanner, that they’re playing half-court tennis. Is this surprising? Does it tell you anything?

Tanner Greer: I asked all these people about their ideal China policy, what they want to achieve, what the world would look like after their policies were implemented, and what tools they wanted to use. Everyone had extensive answers and freely expanded on these questions.

I also asked them, “When you do X, what do you think the Chinese will do in response?” No one ever brought that up on their own. Some could give reasonable answers when prompted, but they all needed prompting to view it as an action-reaction dynamic.

In some ways — and this thought has only occurred to me during our conversation — this is almost the opposite of Trump himself. Trump is highly tactical, focusing on moving from one thing to the next, whereas everyone else has these grand plans. They have specific end states they want to achieve with China and programs of things they want to do, without thinking about the Chinese response.

Trump, conversely, seems to think more about potential responses, and intentionally does things that will provoke the response he wants. I think this disconnect is probably a problem. It makes it difficult to bridge Trump’s approach to policy with what these advisors want to do, even if they weren’t all pursuing different objectives.

The Chinese will respond. I would feel more confident if more people had thought through the Chinese response to their economic policies. On the economic side, many of these people would hold similar economic ideals whether or not China existed. For some, China serves as a convenient boogeyman. For others, China provides evidence of how American economic policy could improve.

But rarely is China the reason they arrived at their positions — it’s more of a case study supporting what they already wanted to do. I suspect there might be several surprises when we act and the Chinese respond in return.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s close on that. Tanner Greer, you’re a Mandarin speaker and Council on Foreign Relations researcher working on the open translation project — how will China make any sense of all this?

Tanner Greer: The first question, which I don’t know the answer to, is how much discernment do they have of the intricacies I’ve described? If they were very strategic, they would analyze these different factions and maneuver in ways that strengthen some over others. I doubt they will manage that. The Chinese haven’t demonstrated a good track record of understanding American politics or manipulating it effectively during the Xi Jinping era.

Jordan Schneider: I don’t think Tanner’s going to be consulting for them anytime soon. This podcast is all you guys are going to get.

Tanner Greer: They could read my report since it’s publicly available. But whatever intern at the embassy reads my report, the information getting filtered up to Xi Jinping involves steps that probably matter. I’ve met or seen some people at the embassy, and many are actually quite savvy about American politics. This suggests there’s something between the ground-level analysts in DC and Xi where information gets distorted.

Alternatively, there may be other pressures in their domestic system where people take actions for reasons beyond just anticipating American responses. There’s a mirror problem here.

In the short term, my guess is they’ll position themselves as the reasonable actors on the international scene in contrast to the chaos of the Trump administration. If they’re smart, they’ll emphasize the predictability/unpredictability dynamic I’ve already mentioned. You can already see they’ve started releasing propaganda about how they support trade and international cooperation. They’ll continue that approach.

The more interesting question is whether they’ll take a harder or more accelerated position on Taiwan. Unless Taiwan does something provocative, I suspect the answer is no. They’ll likely view the chaos in the United States as confirmation of their narrative that the East is rising and the West is falling — that is, that time is on their side.

My guess is they’ll conclude, “We just need to be the calm, stable power while the Americans appear erratic, and everyone will see who’s the better partner. Taiwan will observe this dynamic, too.” The Chinese will believe they’re only getting stronger militarily and don’t need to take immediate action. But that’s just my assessment. Many factors could alter this trajectory.

Jordan Schneider: One last question for you, Tanner. History is contingent. Trump is a unique figure. DeSantis could have won the primary. Trump could have been impeached in January or survived two assassination attempts during the election. What was and wasn’t inevitable given a Republican president winning in 2024?

Tanner Greer: The developments with Ukraine were not inevitable. What has happened in Europe was not predetermined. That’s the first point.

The general trajectory on the geopolitical side — the department orienting strongly towards Taiwan — was to some extent inevitable.

The real interesting question concerns tariffs and trade. A larger reckoning with the current international trading order was coming regardless. Personally, I believe this order is not sustainable as it has been. I hear many neoliberal voices suggesting we just need to return to Obama-era policies and that everything would be fine. This perspective is utterly insufficient, especially if you’re a liberal who dislikes Trump. You must recognize that this order in some ways produced him.

Whether Trump had died last summer or not, we would be experiencing some sort of reckoning with what the global order would look like. Would it happen exactly this way? Probably not. The post-Bretton Woods era, the globalized era from the 1970s until now — whatever we want to call this world — is naturally reaching its conclusion. The question is how much agency we’re going to try to exercise over this process, and how much agency anyone can have.

I don’t have simple answers. The Trump team’s divisions and Trump’s erratic personality certainly make it more difficult to exercise control against what I’d call the friction of the universe. But there was no path back to 2016 at this point.