EMERGENCY POD: Setser on Biden's Electric Curtain

The IRA was the carrot. Here comes the stick.

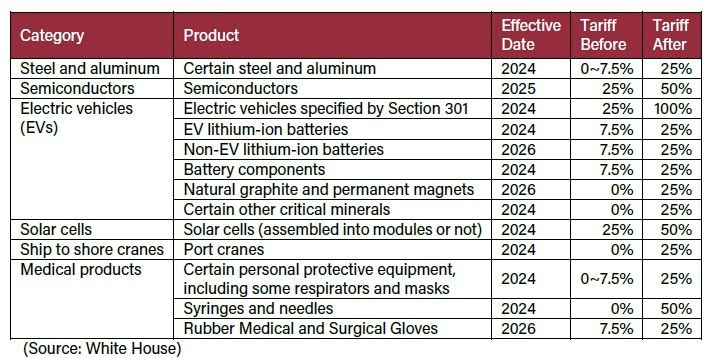

The Biden administration has announced a slew of tariffs against China, including a 100% tariff on Chinese EVs. What took so long? How did regulators decide what to tariff, and how much the tariffs would be?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed economist Brad Setser, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and a former economist in Biden’s USTR.

We discuss:

Whether the national security justification for tariffs on EVs makes sense;

Why the Biden admin waited so long before imposing these tariffs;

Whether the tariffs will unjustly protect low-quality American carmakers from healthy competition;

How the policy response to today’s Chinese EV manufacturers differs from the response to Japanese automakers in the 1980s;

How the different tariff percentages were chosen;

… and more!

What is being tariffed and why?

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with a brief history of how we got here. What is the process that ended up concluding on May 14, 2024?

Brad Setser: The process started with the imposition of Section 301 tariffs in the Trump administration. 301 is sort of like the US unilateral judge-and-jury tariff law. It states that if there's an undue burden on US commerce, then the US can impose tariffs that are meant to offset that undue burden.

The original 301 case was centered around technology transfer and IP theft, which led to a series of negotiations with China. China responded to the initial $50 billion of tariffs with their own $50 billion of tariffs, and then Trump responded with an ever-escalating and expanding set of tariffs. $50 billion became $250 billion, and then another $110 billion was added by the Trump administration.

Trump granted some exclusions to these tariffs, and the Biden administration inherited an open question of what to do with these tariffs. There is also a statutory review of 301 tariffs after a four-year period.

Today, Biden announced the conclusion that some of the tariffs needed to be increased to better serve the goals of the original 301 case. Those goals include holding China to its commitments, which it didn't meet under the phase one agreement.

Thus, what the Biden administration eventually concluded was that this review should change the structure of tariffs around a set of products that the Biden administration judged to be of strategic importance to America's future industrial development. Those areas also happen to generally be areas where China itself has had an active industrial policy.

The net effect is, to a significant degree, fighting to fire with fire.

China has a pretty restrictive policy towards imports of electric vehicles and batteries. It doesn't need to be that restrictive because companies have become competitive.

But when China’s EV and battery industry was getting started, China didn't let foreign producers’ imports qualify for its subsidies. China’s always had actually pretty high tariffs around the auto sector and solar ships.

China has clearly had industrial policies. These tariffs took on an aspect of responding to China's industrial policies in support of the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act. Biden’s goal is to make sure that an indigenous American electric vehicle and battery industry doesn't get overwhelmed by Chinese supply.

Jordan Schneider: I did a show way back in 2019 with Doug Irwin, who has a fascinating book about the political economy of tariffs.

Clearly, some of these industries have real political salience. The Detroit automakers in 2008 were prominent enough to get a bailout.

But this also includes tariffs on some novel things – such as lagging edge semiconductors, shipped-ashore cranes, syringes, and needles – which don’t appear to be motivated by a protectionist impulse to save unproductive jobs.

Instead, the Biden administration has decided that dependence on China is a national security issue that needs rectifying, and his solution is to use trade barriers as well as subsidies and industrial policy.

Brad Setser: That's right. In manufacturing, China is now a superpower. 30% to 33% of global manufacturing is in China, which is 15% to 20% of the global economy. China is a superpower.

The US has gone through three phases in its response to the challenge created by China's emergence as the world's greatest manufacturing power.

The first phase was a dominant sense that China's emergence as a manufacturer was complementary to the US economy. This was the idea that US companies could get cheap inputs and make certain consumer goods at a lower cost, which would be good for the US economy. This idea assumed that over time, a wealthier China would be a growing market for things like solar cells, aircraft, semiconductors, and patent-protected pharmaceuticals, which the US economy stood to benefit from also.

The second phase was a recognition that the organic development of China's economy and its manufacturing power wasn't simply complimentary, and that in some specific sectors, telecommunications equipment being the obvious one, Chinese firms were emerging as potent competitors and they were doing so with a certain element of state backing. Huawei wasn't state-owned, but Huawei got plenty of support through contracts inside China from the state, telcos, a lot of support when it's going out and exporting, and a lot of subsidies for the development of its chip business. There was a hope that through negotiation you could convince China to change its ways, to back away from certain industrial policy practices, to liberalize, to go back to reform and opening up.

Now we're in a third phase where no one expects China to reform and open up. We are now responding with our own industrial policies. We're not going to abandon sectors just because China has used state resources to prioritize them and built up capacity.

We're trying to develop those sectors ourselves, and we're using both money and border restrictions to achieve that goal.

Jordan Schneider: This gets at one of the things that is a sort of pet peeve for me. When Biden talks about trade policy, he says things such as, “American workers and businesses can out-compete anyone as long as they have fair competition.”

Well, I'm sorry, but “fair” doesn't have a lot to do with it. China's actually really good at making stuff now. The concern I have is that this mindset doesn't internalize the fact that America is can lose because of domestic political decisions.

US failure on EVs isn’t simply a downstream consequence of the fact that BYD got some undermarket loans back in 2015.

There are clear firm dynamics and regulatory dynamics that have made the EV rollout in the US a lot less successful. Both Western and East Asian carmakers are less capable of producing vehicles at the quality and price that China is offering.

I worry that there is actually a skill issue, and tariffs will just get us into the same position we’re in with US steel.

Is the Biden administration just buying time for GM to make poor-quality cars? Could there be potential benefits to forcing US automakers to out-compete BYD in the US?

Brad Setser: Competition can strengthen you because you have to emerge as the best form of yourself. College basketball coaches want to have tough games to prepare themselves for the tournament for a reason. But competition can also wipe out your industry.

If competition risks killing the US EV industry, making us totally reliant on China, then that competition isn't a helpful strategy for making a strong, competitive domestic industry either.

There was, to a degree, a risk that Chinese supply would come to dominate the US market. This isn’t just about BYD – Tesla's economic dynamics made them decide to produce cars in China for sale in the US market. GM and GM's partners could produce EVs in China for sale to the US. Same with Ford. That would not strengthen our own capacity to make our own EVs. It might help GM and Ford survive as brands, but it wouldn't bring that technology nor that expertise into the US.

I share the Biden administration's judgment that there was a real risk that the end result of open competition would have been the transfer of the whole industry to China, not a stronger US industry.

Next, I don't think it is quite right to either say “China's industry has only emerged because of the subsidies,” or to conversely make the argument that “China's industry just reflects the strategic and technological prowess of a few Chinese firms, which is why we should welcome them into our markets so that we can learn from them.”

The history is much more complex. Some of China's early EVs were not great. They clearly were benefiting from subsidies. There were a lot of subsidies thrown into the development of both batteries and the supply chain for minerals that eventually become batteries.

This was a conscious, strategic decision to shift to EVs, in part because China wanted to shake up the industry because Chinese brands weren't succeeding at building conventional combustion vehicles.

There are cases where failed EV manufacturers in China are resurrected with investments from Three Gorges, which is a power company in the local province, which is hardly this story of great innovation leading to winning the market.

All that said, the EV industry drew on China’s existing manufacturing skill set – making an EV is analogous to producing high-quality electric machinery or appliances. EVs and cell phones are both powered by the same underlying battery technology.

But I also don't think it is fair to say that the Chinese government played no role in this.

The reality is that it was a government policy that was very successful at nurturing these very efficient and innovative firms that we are now seeing today.

Jordan Schneider: For a deep dive on that specific topic, check out our show with John Helvaston, who wrote a number of papers exploring the interaction between the Chinese EV and the state sector in great detail.

Are these tariffs unprecedented, or just a repeat of the 1980s?

Jordan Schneider: Let's talk about the potential resolution of this. We're up to 100% tariffs if you are importing directly from China, which basically means that there are not going to be cars imported directly from China.

Interestingly, the US hit the same roadblock in the 1980s with Japanese and Korean automakers. The compromise that American policymakers landed on was to accept foreign car brands as long as they were manufactured in Mississippi, for example. Now we have a lot of Hyundai and Toyota factories in the US. It seems like that is not necessarily going to happen with BYD.

What's your take on whether such a resolution might be applicable in today’s EV market?

Brad Setser: Well, just as an observation, I think the history of the eighties is actually not very helpful.

There are obvious differences. One difference is that Korea, Japan, and Europe are allies.

Second, the incentives didn't just come from tariffs, they came from a big adjustment in the dollar. Toyota, BMW, and Mercedes set up shop here because they actually had an economic incentive to invest and build out their US supply chain.

By the way, in the US we still import a meaningful number of cars from Japan, Korea, and Germany. We are still the biggest market in the world for imported cars by far. We shouldn't forget that.

But the third thing is that, in the 1980s we weren't in a world of smart cars and the internet of things. A self-driving car is a surveillance camera on steroids connected to the global ether. There's massive computing power processing all the images and telling that computer how to process all the information it is receiving. There's a surveillance angle that didn't exist in the 1980s.

I don't think we are so far behind the Chinese carmakers.

I wouldn't go so far as to say we need to import all the technical know-how from China. Tesla’s leadership has maybe spent too much time pursuing extracurriculars, but Tesla knows how to make competitive electric cars, no question about it.

I actually don't think GM is that far behind either. They just went a different route. They went for costly builds because they wanted to build electric substitutes for their money-making models, which are their heavier pickups and SUVs.

Hyundai, which is going to produce in the US, has already built a pretty significant business with a broader range of electric vehicles.

China’s vehicles are available at a much lower price point — that’s what makes them competitive. But they are cheap because the yuan is weak and because there hasn't been much upward pressure on wages in China.

And in some cases Chinese manufacturers, because the domestic market has been very competitive, have just abandoned performance and went for a luxury vehicle experience where you're driven around in a home entertainment system. We could probably do the same thing. The question is whether there's a market for it.

I'm not as pessimistic as some. I do think we are going to import some of China's battery technology through licensing arrangements, and I think that's fine. The harder questions will arise when we confront the technology for self-driving and AI-powered cars.

You can get some pretty scary national security scenarios when all those cars are connected to computers run out of Beijing.

Jordan Schneider: Well, in any industry you can come up with a national security rationale for wanting to have domestic production. The question is — how important is it and how much are you willing to pay? The cost for now is that we're basically going to have a bifurcated car industry for the foreseeable future.

Brad Setser: I guess I agree it's a big decision, but just for the record — we've already had a bifurcated car industry. Cars for the US market were made in the US, Korea, and Japan. Cars for the Chinese market were made in China.

The Chinese market has a very low import penetration and used to have almost no exports. It was self contained in part because of the joint venture requirements of that industry.

The question was whether we were going to have an integrated market that included China. We have not in the past. But the decision not to integrate our auto markets at this point when China's auto sector is genuinely innovative and genuinely competitive is a consequential one.

Jordan Schneider: One industry where the trade is not going to be zeroed out by these new tariffs is batteries.

There’s a 25% increase for lithium-ion EV batteries and a 25% increase in 2026 for non-EV lithium-ion batteries. What's going on here, Brad?

Brad Setser: Well, weirdly, the Trump battery tariffs were inconsistent. There was a 25% tariff on EV battery cells for cars and a 7.5% tariff on EV battery packs, which led to some pretty significant imports of EV battery packs.

If you look at dollar figures, the tariff on EV batteries is the biggest one because a large unnamed American electric vehicle producer is relying more and more on Chinese battery packs.

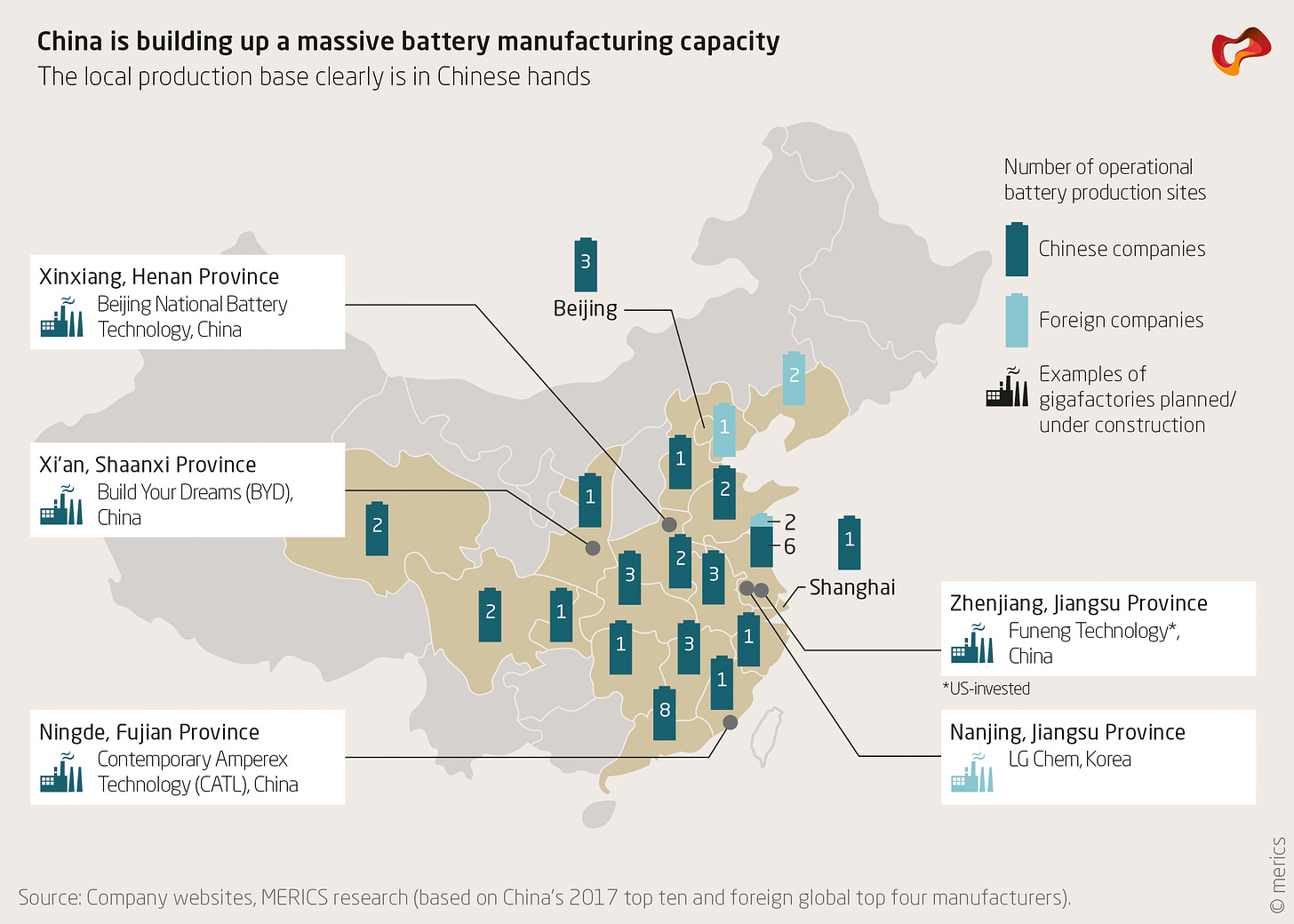

If you want an independent battery industry and an independent battery supply chain, these restrictions are necessary because there is so much potential capacity coming out of China.

We want a battery industry. Simple. We're spending a lot of money on it with the IRA, and we wanted to make sure there was a demand for all the capacity that the US is trying to build.

What’s the difference between a 100% tariff and a 200% tariff? Are the percentages just darts at a wall?

Jordan Schneider: It strikes me that all of these are round numbers – hopefully there was some sophisticated analysis that went into picking these percentages — is that the case?

Brad Setser: It's not a secret that the 301 tariff lists were initially created to hit a dollar amount that Trump wanted.

For the 301 tariffs, which are basically punitive, you can't calculate the tariff level based on an estimate of damages.

Hence, why make anyone's life more complicated with something that is not a simple round number? The general rule of thumb is that for every percentage point you increase, the tariff trade falls by 2%. A 25% tariff should lead to a 50% fall on your imports.

A 50% tariff should be prohibitive. If it's not, that tells you something. And then when you go from 50% to 100%, you're making a point.

The point is — we don't want to be dependent on China for electric vehicles.

All these calculations end up being arbitrary, but with an anti-dumping duty or a CVD counter-subsidy duty, there is pressure to be overly precise in calculating the offset in damages. In reality, no model is clear enough to recommend an 8.9% tariff.

Conversely, in the 301 space, because the structure is tied to an undue burden on US commerce, it's an offset to Chinese retaliation, and it’s been modified over time – there's no point in trying to have a decimal point estimate because that is not the basis for this kind of tariff action.

Do we really need 100%, or is that just a political statement? 50% should be prohibitive. For some sectors, 50% may not be prohibitive because Chinese battery producers are really quite competitive, but they also don't qualify for IRA incentives.

Then, for some other sectors, like legacy chips, the tariff actually doesn't matter that much, because most legacy chips aren't imported as chips, they're imported as part of a final product.

Solar is also performative because the US imports a lot of Chinese solar content through Southeast Asia. We import wafers and cells that are put into panels in Southeast Asia.

It doesn't really matter what the tariff is if the product is already tariffed out the wazoo.

Jordan Schneider: Fair enough. You know, Trump said today that his plan is to make the tariff 200%.

Brad Setser: Ha, Biden should have countered with 400%. Why not, right?

Subscribers get access to part 2, where we discuss:

The risks of China’s overcapacity in solar panels, legacy chips, and permanent magnets;

Why syringes matter for national security;

Why the tariffs didn’t include pharmaceuticals produced in China;

Whether Xi Jinping will retaliate against these tariffs using Panda Diplomacy.

Are overcapacity risks overblown?

Jordan Schneider: What do you think about the concept of overcapacity?