Despite leading the world in AI innovation, there’s no guarantee that America will rise to meet the challenge of AI infrastructure. Specifically, the key technological barrier for data center construction within the next 5 years is new power capacity.

To discuss policy solutions, ChinaTalk interviewed Ben Della Rocca, who helped write the AI infrastructure executive order and formerly served as director for technology and national security on Biden’s NSC, as well as Arnab Datta, director at IFP and managing director at Employ America, and Tim Fist, a director at IFP. Arnab and Tim just published a fantastic three-part series exploring the policy changes needed to ensure that AGI is invented in the USA and deployed through American data centers.

In today’s interview, we discuss…

The need for new power generation driven by ballooning demand for compute,

The impact of the January 2025 executive order on AI infrastructure,

Which energy technologies can (and can’t) power gigawatt-scale AI training facilities and why Jordan is all-in on GEOTHERMAL,

Challenges for financing moonshot green power ideas and the role of government action,

The failure of the market to prioritize AI lab security, and what can be done to fend off threats from adversaries and non-state actors.

Watch below or listen now on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app.

Constructing Compute

Jordan Schneider: Ben, why were you, as an NSC director, spending time in SCIFs dealing with energy permitting policy on federal land?

Ben Della Rocca: That’s a great question. Spending so much time reading about environmental permitting law and watching law school lectures on how the Clean Air Act works was not how I envisioned spending my time as an NSC director, but there I was doing just that in the SCIF for my AI work.

The United States has a lead in AI thanks to our thriving innovation ecosystem and the immense engineering and other talent. However, that lead isn’t guaranteed. Which country will lead in artificial intelligence will come down more and more to where AI can be built most quickly and effectively.

By “built,” I’m not just talking about the technical engineering challenge of how to do large-scale AI training runs from a computer science standpoint, but also the physical building challenge. This involves developing the large-scale computing infrastructure and energy infrastructure to execute these ever-growing AI training runs.

What became clear to us in the last administration was AI’s significant impact on national security, the economy, and scientific advancement. We also saw an exponential increase in the demand for computing power and energy resources to develop frontier models.

The amount of compute required by frontier AI models is increasing by a factor of 4-5x annually based on publicly available statistics. That’s an exponential pace of growth. Even when you factor in increasing energy efficiency of computational resources and other countervailing factors, you’re still looking at gigawatts of electricity needed to execute training runs at the frontier within the next few years.

There are multiple power-related challenges when it comes to developing and deploying AI. Assuming current trends continue, you need gigawatt-scale training facilities to develop models at the frontier — that’s one set of issues. Then there’s a separate but related set of issues around developing a robust network of potentially smaller-scale data centers around the country to actually use these tools effectively in different locations. This is a significant energy challenge as well.

At the National Security Council, I led the White House’s work around AI infrastructure and developed the AI infrastructure executive order that came out in January 2025. What the executive order tries to do is directly address that first challenge — how to build these large gigawatt-scale training clusters that, assuming the current paradigm of AI training continues, will need to be built for the United States to maintain its lead.

Jordan Schneider: That’s a tall order you set for yourself, Ben. In your mind, what parts of the executive order will matter most when building out AI data centers in the US?

Ben Della Rocca: The executive order includes a wide range of things that address not only how we bring gigawatt-scale data centers online in this country, but also a broader, distributed network of data centers around the country. There’s a lot in there, but I’ll highlight three key mechanisms.

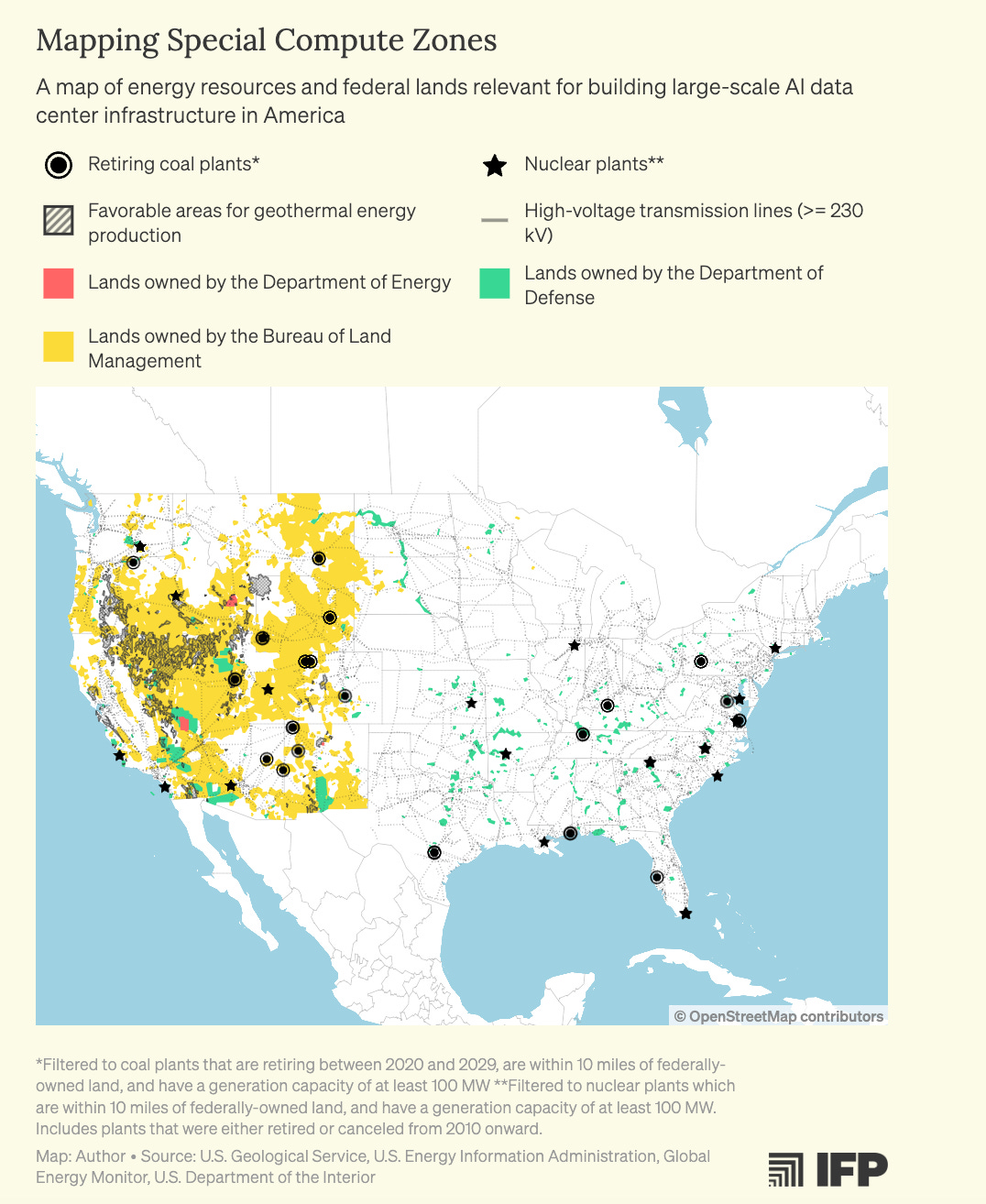

Construction on federal lands — the centerpiece of the executive order establishes a mechanism by which AI data centers can be built in a streamlined and more efficient way on federal sites owned by the Department of Defense and Department of Energy. There’s a huge value proposition to building on DOD and DOE sites because by building on federal lands, you bypass many of the state and local land use permitting requirements that usually make data center construction and similar projects take such a long time. Additional burdens on the federal permitting side are taken on as a result, but the federal government can and will be doing much under the executive order to make those processes proceed as expeditiously as possible.

Regarding bringing new power generation online — operating gigawatt-scale data centers will require a lot of new power added to the electric grid. This is challenging for numerous reasons, including permitting requirements that complicate construction broadly, delays with interconnection to the electric grid, and other required approvals. The executive order directs the Department of Energy to establish requirements to collect and share information with data center developers regarding unbuilt power projects that have already received interconnection approvals to accelerate the power procurement process. It also directs the Department of Energy to engage utilities to reform their interconnection processes for faster progress.

Regarding transmission — the Department of Energy is directed to use some of its powerful authorities to partner with private sector transmission developers in building transmission lines much more efficiently and quickly than business as usual, and to take part in the planning process as well. You also have other actions to bolster the supply chain for transmission and grid equipment, which would be really useful for the long-term vitality of this industry.

Between these sets of things and other actions to expedite the permitting process within the federal government’s authority, the executive order lays out a pathway for building gigawatt-scale facilities on the timelines that we expect leading developers will ultimately need for AI training.

Jordan Schneider: Tim, what's missing from the executive order?

Tim Fist: We highlight two big gaps.

The EO comes along with a clean energy requirement. All the energy that you're producing to power these data centers needs to come from clean energy sources. It allows the use of natural gas with carbon capture, but that technology can’t be implemented on the timescale required.

While building on federal lands owned by DOE and DOD allows you to bypass a lot of state and local permitting issues, it does open up the issue of NEPA, which automatically applies if you’re building on federal land.

Our recommendation around that is using the Defense Production Act to speed up permitting on federal land, as well as resolve supply chain issues.

DPA gives the President broad authority to intervene in the economy where this is seen as necessary to ensure the supply of technology that's deemed essential to national defense. Our claim is that AI definitely fits within this scope.

Because the most powerful AI systems are now being developed by private firms, a lot of the DoD's future capabilities are likely going to come from models that are trained in data centers operated by private firms.

OpenAI recently announced a partnership with Anduril to bring its models to the battlefield. ScaleAI has built a version of Meta’s Llama, which they call Defense Llama, to help with military planning and decision making. Palantir is building platforms for DoD as well.

Arnab Datta: We mentioned two authorities in the DPA. Title I, which is prioritization, would allow the federal government to tell contractors to prioritize transformers, turbines, and other hardware for AI data center use. The other authority in the DPA is Title III, which is a financial assistance authority. There are also authorities within the DPA and Title III where you can streamline some of these permitting issues that Tim described.

Jordan Schneider: Can you explain how DPA authorities would help?

Arnab Datta: I’ll use a practical example — right now, natural gas turbines are sold out. GE Vernova said they could be sold out past 2030.

DPA would allow the president to say, AI is a national security priority, and those data center turbine contracts need to be fulfilled first.

I don’t want people to think that our idea and what we’re proposing is about getting out of environmental rules to build this infrastructure. The important thing is that we’re talking about using these to streamline the procedural laws associated with environmental review.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that an environmental review wouldn’t be conducted prior to leasing federal land, for example. Finding ways to limit the likelihood of litigation could be very important here, and that’s where some of the national security exemptions are most useful.

The Geothermal Goldmine

Jordan Schneider: Let’s take a step back here, because we got really deep, really fast. The renewable regulations will obviously disappear in the next few weeks, and NEPA was just nerfed by the Trump administration.

The worry for a hyperscaler might be driving their data center through the process and then getting sued four years from now in a different administration. But even then, the data centers will already be built. We’ll have AGI by then. No administration is going to shut that off because you took advantage of a permissive regulatory environment.

I’d like to discuss the hard constraints when it comes to actually building and deploying the electricity needed for these data centers. A fascinating part of Tim and Arnab’s work was going through all the potential technologies that could provide the marginal electricity needed for these data centers, and ranking them by potential. Let’s do overrated and underrated. What are three overrated sources of electricity that get too much attention in the broader discourse about the future of AI?

Arnab Datta: I don’t love the word “overrated,” but there is sometimes an implication that natural gas makes this super easy. The reality is that gigawatt-scale energy projects, particularly off-grid projects that many compute companies are moving toward, represent massive investments.

By off-grid, I mean not connected to the transmission system — you’re building close to your data center and it’s exclusively powering your facility. This is an extremely expensive and risky investment regardless of how much cash you have on hand. Building energy infrastructure at a gigawatt scale is very costly.

When discussing natural gas, yes, it’s a proven technology, but there are stranded asset risks. If an AI data center outlives its useful life in that location, or if something becomes more cost-competitive and a company wants to switch, you face challenges. Natural gas is important and should definitely be part of the mix, but I wouldn’t say it’s an easy decision. There are supply chain challenges, and the notion that “we can solve this with natural gas” oversimplifies the issue.

Jordan Schneider: Tim, what do you think?

Tim Fist: The obvious one is the much more long-term technology — fusion. We see some hyperscalers signing power purchase agreements for fusion energy. A power purchase agreement is a commitment to buy a fixed number of kilowatt-hours at a future point, and the fact that they’re buying this for fusion is rather incredible when there isn’t a viable commercial fusion reactor that’s ever been demonstrated.

This technology is clearly so far off that it won’t matter over the timeframe we’re concerned about, which is how we ensure we can build this infrastructure over the next five years.

Ben Della Rocca: Each approach has real downsides. There are real risks, problems, and inefficiencies that aren’t fully recognized.

To pick one where there’s sometimes optimism that should be qualified — we need to be realistic about nuclear options in particular. Nuclear energy is something I would be very excited about in a longer-term timeframe, such as the 2030s. However, it’s very difficult to see that being part of the solution for the late-2020s challenges we may face regarding AI’s energy use. We should be realistic about the timing involved.

Tim Fist: We’re at this weird point in history. Twenty years ago, the answer would have been obvious because renewables were completely non-viable, and there weren’t exciting next-generation technologies coming along.

Right now, we’re at a point where multiple technologies are approaching the same level of cost competitiveness simultaneously. Large-scale battery plus storage is now better than natural gas in many areas. Advanced geothermal is becoming super interesting but hasn’t been properly scaled or demonstrated yet. Small modular reactors are just coming online and are probably the next big thing once we can scale them up.

In the near term, natural gas seems like the obvious solution. However, it will likely become an obsolete technology within about 10 years. That’s the core problem we’re trying to grapple with.

Jordan Schneider: I was disappointed about dams. I thought they could be a viable option, but you disabused me of that notion. They’re too slow or not big enough. There’s no new innovative dam technology that’s been developed over the past 70 years, which I was disappointed to discover.

Arnab, what are you excited about?

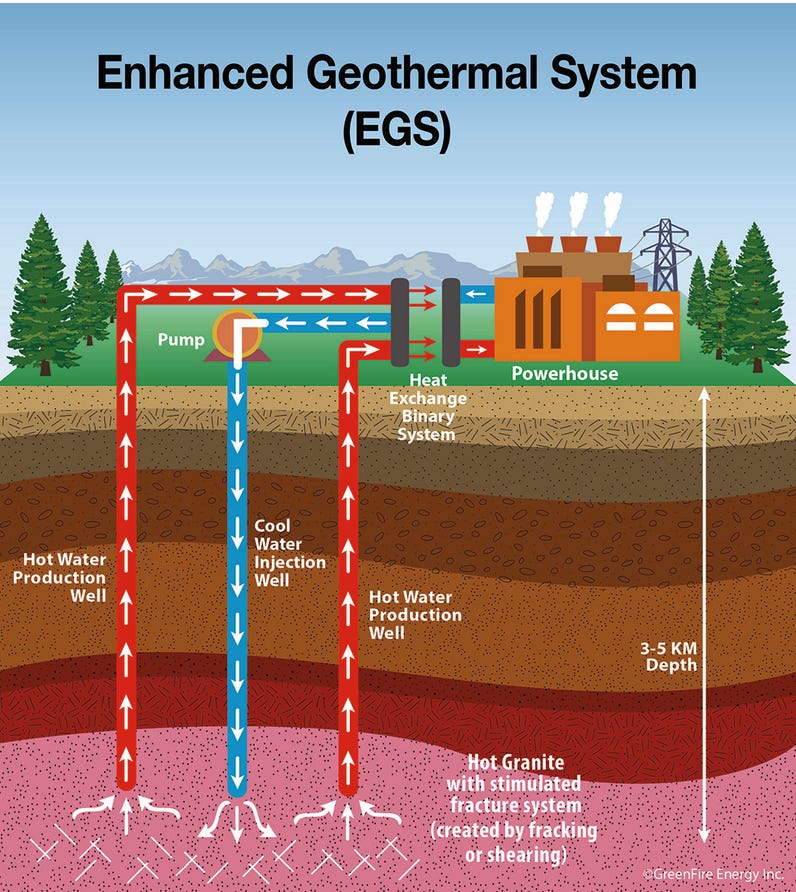

Arnab Datta: I’m incredibly excited about next-generation geothermal energy. This is energy produced from heat in the Earth’s crust — the heat beneath our feet, as it’s often called. We’re pioneering this energy technology because of our experience with fracking and how we developed drilling techniques that led to the shale revolution.

There hasn’t been enough demonstration yet, though some companies are innovating quite rapidly. The scale potential is remarkable, and it’s an area where the US can really lead because we have an oil and gas workforce where 61% of workers have skills directly transferable to geothermal. We have a supply chain for fracking and shale production that’s ready to go and transferable to next-gen geothermal. The potential is incredibly high, and I wish we were doing more to support it.

Jordan Schneider: Can we stay on the technology for a moment? How do I drill a hole and get electricity out of it?

Arnab Datta: Basically, you’re drilling into the Earth’s crust where there’s substantial heat, and you’re pumping fluids down into that heat. The fluid gets heated up, and you’re circulating it back to a steam turbine that generates electricity. That’s the simple explanation.

Jordan Schneider: So it’s just like a steam boiler with the Earth’s core as the power source? That’s incredible.

Arnab Datta: Yes. There are multiple types of systems. Traditional geothermal requires three elements coming together naturally: heat, fluid, and a reservoir. These are natural geothermal reservoirs.

What next-generation geothermal does is create artificial reservoirs. You’re digging and fracking to create cleavages in the crust, and then cycling fluid through it. This is safe, to be clear. It has been tested and demonstrated. This isn’t something that’s going to damage the Earth. That’s the basic explanation for how it works.

Tim Fist: The amount of heat energy stored in the Earth’s crust that you can access via enhanced geothermal vastly exceeds the amount of energy in all known fossil fuels by several orders of magnitude. This is an abundant source of low-carbon energy without any of the intermittency problems of solar and wind that you can also access using many of the same tools we’ve developed for large-scale fracking.

This technology has already been deployed. Google is powering some fraction of its data centers with this. At this point, it’s primarily a scaling problem.

The areas where you can extract the most heat from the Earth’s crust using these methods also overlap substantially with the areas where you have federal land that can be readily leased. It’s a perfect recipe for solving this problem.

Jordan Schneider: The Earth is warmer under Nevada?

Arnab Datta: The heat is closer to the surface. To add one thing to what Tim said as an example: you have to drill three wells to produce about 10 megawatts of energy in something called a triplet. To reach five gigawatts, which is our goal by 2030, you would need to drill 500 of those triplets.

Jordan Schneider: This is child’s play.

Arnab Datta: That means 1,500 wells. We have drilled 1,500 new wells multiple times in the shale region of this country in a given year. This is not that many new wells to drill, if we can perfect the technology. We’re very well-positioned to take advantage of this, if we can get there.

Ben Della Rocca: I would underscore that geothermal is the single energy source I’m most excited about, in terms of technologies that are underrated by the broader public.

AI itself provides an opportunity to create much of the backstop demand that can funnel capital to the industry and incentivize development and technical advances needed to make the United States a global leader in this technology and advance our energy leadership more broadly.

As Tim mentioned, traditional geothermal resources are primarily available in the western United States. This overlaps heavily with places where large amounts of land are owned by the Bureau of Land Management. One of the sources of delay with building geothermal projects on federal lands has been federal environmental permitting reviews, which take time.

The executive order has directed the Department of Interior to find ways of conducting these reviews much more quickly — eliminating redundant reviews at multiple stages in geothermal projects and creating what are called “priority geothermal zones.” These are areas where the Department of Interior will focus its permitting efforts to move the process along as expeditiously as possible.

Ideally, these zones would overlap with places where AI data centers are being built, to ensure that all efforts are moving in the same direction. There’s a lot more to be done, but we’ve seen a valuable starting point to accelerate development in the geothermal space.

Jordan Schneider: What is the environmental consideration? We don’t even have oil gushing out. Are there endangered species in rock 20,000 feet below the Earth’s surface? It’s just ten guys and a drill.

Ben Della Rocca: That’s a great question. Certainly, the environmental repercussions are fewer than with traditional fracking for the oil and gas sector. With any construction project like this, you have to build a power plant, which involves some change to the natural environment. If there’s an endangered species right where you want to build the power plant, that will be a factor in the environmental analysis. Drilling deep down can potentially cause some impacts to the broader region as well.

The environmental burdens are significantly less, which is why there’s potential for the permitting to go more quickly. It’s a question of marshaling the right policy resources to ensure we’re all moving as quickly as possible given the lesser concerns with this technology.

Jordan Schneider: What are some lessons from the shale revolution that can potentially apply to the US government helping incentivize the development and production of geothermal?

Arnab Datta: In the 1970s, coming out of the Arab oil crisis, we made a conscious effort to support the non-conventional production of energy. By the mid-2010s, we were the leading producer of oil and natural gas.

How did that happen? There were four key policy interventions that occurred over those decades that I would emphasize. My colleague at Employ America, Skanda Amarnath, and I wrote about this last year.

First, there were numerous research and development and cost-share programs to innovate in drilling and develop new techniques. The Department of Energy worked directly with Mitchell Energy, sharing some of the drilling costs to test non-conventional means of production.

Second, there were supply-side production tax incentives and demand-side price support. On the supply side, there was a Section 29 tax credit — essentially a production tax credit for non-conventional sources. An analogous current example is the Inflation Reduction Act, which supports production for new types of energy. It’s important that those credits remain in place.

On the price support side, there was targeted deregulation in the Natural Gas Policy Act in 1978 that exempted energy produced from non-conventional sources from the existing system of price controls. This essentially created a price support incentive. People describe it as good deregulation, but its ultimate purpose was to create a more competitive price environment for this type of production.

Third, there were permitting changes that altered the regulatory environment. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 established a legislative categorical exclusion, meaning certain types of production with specific geographic footprints could undergo the lowest level of NEPA analysis and get approved more quickly.

Fourth, and often underrated, was a highly accommodative macroeconomic environment. The shale boom and major productivity increases happened at scale in the late 2000s and early 2010s when interest rates were low. Companies could take on cheap debt and iterate, with abundant capital available for them to enhance productivity to the point where production levels increased even as the workforce declined because drilling techniques became so efficient.

These four factors help explain what happened in the shale revolution. We need to figure out how to compress that timeline to just a couple of years for next-generation geothermal energy.

Jordan Schneider: How far away are we today from these awesome steam boilers?

Arnab Datta: Fervo is currently building what I believe is a 400-megawatt facility. I don’t know the exact state of where that stands in project development since it’s a private company and I’m relying on public information. They’ve demonstrated that their technology works at a small scale.

Tim mentioned the Google facility. One of their smaller installations is powering a data center at around 40 megawatts. There’s also a company based out of my home city, Calgary, Canada, called Eavor that’s working with horizontal drilling. They have a small demonstration project as well.

The real question is whether we can achieve scale. The major challenge for these companies is securing enough capital to demonstrate that the technology works and can produce utility-scale electricity.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned capital. Where hasn’t this been coming from, and where should it come from to realize this vision for geothermal over the next five years?

Arnab Datta: That’s a great question. In our report, we discussed the challenge of financing these next-generation technologies — whether geothermal, small modular reactors, or others. The fundamental challenge is that despite the promise, there’s tremendous uncertainty associated with developing these technologies.

The key is finding investors willing to accept this level of uncertainty in project development. They need to be comfortable covering costs when they increase because permits take longer than expected, supply chain issues arise, or interest rates climb, making capital more expensive. All these uncertainties accumulate, making equity investors reticent to invest at a sufficient scale.

There are only a handful of venture capital firms that engage in this type of investing, and they reach their limits quickly. Banks won’t do it because the risk of failure amid such uncertainty is too high. The government is playing a role — if you look at the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, they’ve funded demonstration projects for SMRs.

In the shale context, the federal government shared costs with Mitchell Energy for drilling operations. We need some version of that approach now. We also need the federal government to reduce uncertainty.

When you think about technology demonstration, you typically start with a concept paper, hoping to attract investment for the next step — a small-scale project. Once you secure that investment, you aim for a larger-scale project, attracting a bit more funding. It’s a slow, incremental process of building investor confidence. We need to compress this timeline at each stage and reduce uncertainty so companies can invest.

Financing energy projects typically requires three elements — debt, equity, and offtake agreements (meaning someone to purchase the energy once you’ve produced it). Currently, we see headlines about AI companies “investing” in energy projects, but they’re mostly doing this through these power purchasing agreements.

With next-generation energy, there’s substantial uncertainty from factors that aren’t easily quantifiable — permitting and regulatory timelines, physical feasibility, and potential material bottlenecks. One of those three participants needs to own that uncertainty, and it’s generally not going to be through offtake agreements.

You would need very high-premium offtake agreements to cover a level of uncertainty that would give debt or equity investors confidence that their investment won’t fail. In our report, we emphasize that if the federal government can either own that uncertainty by providing capital or reduce it through streamlined regulatory procedures, that could unlock the tremendous amount of capital these companies possess, enabling them to invest directly in projects upfront.

Currently, there simply isn’t enough upfront capital, and that’s the barrier we’re trying to overcome. Many tech companies are sitting on substantial cash reserves, but they’re not directing it toward upfront energy investment. We believe that through federal government initiatives that reduce or assume this uncertainty, we might encourage companies to invest capital directly.

I should note that Amazon has invested directly in an SMR project in the Pacific Northwest, and that’s a model we’d like to see replicated more broadly and at a larger scale. That’s what we’re trying to accomplish.

Jordan Schneider: You gave me some great new acronyms, Arnab. We have FOAK, SOAK, THOAK, and NOAK — first of a kind, second of a kind, third of a kind, and Nth of a kind. We’re still in the “first of its kind” universe. Let me push back on this hype train a little bit. Three years we’re going to go from some cute demonstration projects? I take your point that if you can figure out the pumping mechanism, you have a lot of people happy to live in Nevada for a while and drill big holes in the earth. But AGI’s coming soon. Is this really going to get us there?

Tim Fist: This underscores the validity of an all-of-the-above energy approach, where we’ll want to take multiple shots on goal. We don’t want to put all our eggs in the geothermal basket. If you think about it, we had this staging approach for different technologies that could work really well under this all-of-the-above strategy.

You deploy natural gas plants because you know you can bring those online. They’re going to provide secure, reliable energy, and we know how to build them within a couple of years. Solar and battery storage is a really promising option to build out as much as we can where we can get it online.

Building out geothermal should come alongside that. Small modular reactors would come a bit after that as well. If you want to start thinking about fusion, maybe you’ll bring that online in 20 years. Basically, you want to invest in as many of these technologies as you can at once to address the inherent technological risk with this next-generation stuff.

Ben Della Rocca: One additional thing I’d say to your question, Jordan, is that even within the geothermal space, we can talk about this layered or staged approach where we lean more on some geothermal technologies at one point and then move on to others.

Traditional geothermal technologies are more tried and tested. We’re not necessarily doing first-of-kind projects for some of those geothermal hydrothermal resource projects. Fewer potential gigawatts can be brought onto the grid for that technology, but that might still be enough if we push people to do the right exploration and resource confirmation as they’re building their data centers. That could still be a meaningful part of the solution by 2028.

Beyond 2028, that’s when it might be most realistic for some of the enhanced geothermal projects, which are still in the first-of-a-kind stage, to come online. There’s a bit of phasing that we can do that way.

Tim makes an excellent point that there are different strengths and weaknesses to each of these approaches. It’s unrealistic to think that any one energy source is going to be the sole answer to AI’s energy needs.

With solar and batteries in particular, combining those two resources can be a way to access firm power, and there are downsides to the ability of that to scale in some cases. But it’s also faster to build solar plants, and there’s already been work done to review the environmental impacts of solar developments on some of the Western land under government management. This could make construction of those projects proceed more quickly in certain cases and be an important part of the shorter-term solution.

People really should be looking at a wide range of different options and leveraging different site-specific opportunities.

Transmission and Permitting Reform

Jordan Schneider: Can we talk a little bit about transmission lines and transformers? Arnab, you mentioned that a lot of this stuff may just end up being off-grid where Google’s responsible for building the power right next to its new data center. To what extent does hanging lots of transmission lines over people’s farms or whatever actually matter for all this stuff?

Ben Della Rocca: Transmission is a big part of the equation. You could certainly imagine a world, as you said, Jordan, where all the power resources are co-located and we don’t need to transport any electricity from one site to another. That’s theoretically a solution, but it’s unlikely that when we’re talking about gigawatt-scale data centers, at least in the short term, that we’re going to find sites where you can truly get three to five gigawatts of co-located power. Not saying it’s theoretically impossible, but it would be unrealistic to assume there’s a world where we just don’t need transmission lines to solve this problem.

At a minimum, having transmission lines provides a number of other benefits. First, it puts a much larger range of resources in place. If you have a data center being built somewhere around a variety of different BLM lands that are amenable to different energy sources, you can tap into more of them if you can deliver power from offsite to nearby locations.

Even if you are building power generation on site, there are still many advantages to interconnecting that power to the electric grid. It provides stability benefits, removes some of the need to build a microgrid or other sorts of redundant electrical facilities on site, and mitigates some of the financial risk of your project. If you end up using less power than expected, you could resell it onto the grid. Transmission lines are going to be important no matter what.

I’d like to highlight a couple of things that the executive order tried to set in motion that could help us be forward-leaning on building the transmission infrastructure needed for AI data centers going forward. The most important is that the Department of Energy has some very important statutory authorities to address these problems.

One relatively well-known authority worth mentioning is the ability to establish National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors (NIETC), which are areas the Department of Energy can designate to play a backstop role in accelerating certain permits and approvals if they’re taking a very long time in a way that impedes efficient transmission development. This could be useful in the longer term, though it does take a meaningful period to actually establish a particular region as a NIETC and activate those authorities.

Another set of less well-known authorities that should be fully explored are those allowing the Department of Energy to partner with transmission line developers in powerful ways. Several statutes — such as the Energy Policy Act of 2005, provisions in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — essentially let the Department of Energy create public-private partnerships or work with companies to participate in upgrading, constructing, planning, and financing transmission lines.

Based on analysis that the Department of Energy published under the Obama administration, in some circumstances, these authorities might be used to essentially bypass the need for lengthy state approval processes and allow the Department to play a more efficient role in cost allocation and other processes that state public utility commissions typically handle, which can often take many years to complete.

By using these authorities more aggressively, there’s actually a much faster pathway to building transmission lines, particularly relatively shorter ones. We’re talking about dozens of miles to connect a data center to the grid rather than hundreds of miles of interstate transmission lines. We’re not talking about giant transmission projects, but more targeted transmission builds that DOE can develop with the private sector. This could be a really important pathway to getting more gigawatts on the grid by 2028.

Arnab Datta: I would second basically everything Ben said. Transmission is really important. Some of the short-term solutions Ben identified are exciting, and it would be great to see them implemented.

The reason firms are moving off the grid, making that such a significant factor, is because transmission is just so difficult right now. This underscores the need for longer-term reform and broader permitting reform, with Congress actually taking action. There’s only so much you can do through the executive branch, and it tends to be more imperfect. We need to fix that.

Tim Fist: It takes, on average, 10 years at present to build a new transmission line in the United States. That’s mostly due to these holdups in permitting.

Ten years ago, we built 4,000 new miles of transmission lines every year. Now, it’s more like 500 miles. This is decreasing by a factor of eight.

Jordan Schneider: Ben, what’s a transformer and why does it matter?

Ben Della Rocca: Conceptually, a transformer changes the voltage of an electric current. This transformation process is essential to bring electricity from transmission lines or higher voltage environments to voltages that an actual end-user facility can accept. We need transformers within electric infrastructure to make the power usable for its intended purposes.

The challenge with the transformer industry is that there’s limited capacity with current resources allocated to transformer development to supply an adequate number of transformers needed to build all the power infrastructure that AI is demanding.

Much can be done to support the transformer industry through loan guarantees or other financing options provided or encouraged by government. These measures would allow the transformer industry to invest in the capital expenditures needed to expand their facilities or train new workforce and add workers to existing facilities. All these steps are important for reducing transformer lead times, which I believe are currently in the two-and-a-half to three-year range. Transformers are certainly an important part of the supply chain aspect of this problem.

Jordan Schneider: Since we were talking about the Defense Production Act earlier, now that corruption is in and FARA is dead, how far can a president who really just wants to potentially let their main consigliere who happens to be building giant AI... Just get all the gas turbines before everyone else? Is there any recourse here for something crazy like that?

Arnab Datta: Broadly with DPA use, when utilizing any aggressive or assertive legal authority, it’s important to try to get political buy-in, even if you believe the legal authority is bulletproof and you can do what you want. You still want political buy-in.

The fact that Ben’s here discussing how the Biden administration prioritized this because they saw it as a threat, and the fact that the Trump administration thinks this is a threat and that there should be a national security aspect to AI data center build-out shows there is some consensus.

The DPA is up for reauthorization, which typically happens in a bipartisan fashion. This presents an opportunity to take advantage of that consensus and say, “We are appropriating X amount of dollars and authorities for the DPA to be utilized to help our energy infrastructure build-out for AI data centers,” and put some safeguards on it. If Democrats are concerned about the hypothetical scenario you just described, that can be a negotiating chip for what is typically a bipartisan reauthorization.

Generally, if your concern is around corruption with this issue, there is an opportunity here because the DPA is up for reauthorization. There were actions during the Biden administration regarding using the DPA for heat pumps that Republicans didn’t like, and there were hearings last year on this. Building some kind of legislative consensus could be useful here.

Ben Della Rocca: Arnab has made many great points, and I’d add that in this issue space, the role of litigation shouldn’t be underappreciated in terms of the type of check it can play. This has long been the dynamic with infrastructure projects in many different industries.

The way litigation works around the National Environmental Policy Act and other permitting-related statutes is that lawsuits can allege that permitting requirements haven’t been fully fulfilled. This can result in injunctions that ultimately delay projects while court proceedings are ongoing.

In effect, this means there’s significant value in making sure all the T’s are crossed and I’s are dotted when pursuing an option that uses national security authorities. If you do something that goes outside the bounds of the law or isn’t an airtight legal case, the odds of litigation increase, which can ultimately result in projects being delayed.

If you can’t get past the pre-construction stage because you’re dealing with extensive litigation, that can have huge consequences for the timeline of building artificial intelligence infrastructure, and time has a real premium in this space. The need to ensure that laws are followed very closely here shouldn’t be understated, for a wide variety of reasons.

Jordan Schneider: A lot of the dynamics you both just pointed out also apply to all the NEPA stuff we were discussing. Ben was doing some clever things here and there to try to make it easier for firms, and then Trump just cancelled NEPA, which is legally questionable. We’ll find out. On one hand, it’s probably exciting for Google and Amazon. On the other, you’re opening yourself up to a whole new legal attack surface that wouldn’t exist if we were living in a Harris administration that followed the direction the executive order laid out more directly. Anything else to add on that dimension?

Ben Della Rocca: Your point about the uncertainty here is exactly right. Trump’s rollback of NEPA as it has existed for years certainly has the potential to speed things along, but it doesn’t ultimately eliminate the fundamental statutory requirement, which is for agencies to essentially do their best to review the environmental consequences of their actions.

Without clear regulation, there’s going to be significant ambiguity and uncertainty about what that means, and there will still be years of past practice that courts may look to when determining the exact content of the statutory requirement. The actual magnitude of the impact from efforts to rewrite NEPA regulations remains to be seen. It may take years to play out.

Arnab Datta: One quick thing to add is that it’s important to note that while the NEPA regulation passed by the Council on Environmental Quality was rescinded, every agency still has its rule in place for conducting a NEPA analysis, and those remain in effect. Right now, that’s the rule of the road. There’s a long-term uncertainty that Ben is right to discuss here, but in this immediate moment, the regulatory framework still exists for agencies, and that’s important for people to know and continue to comply with.

Attaching Strings

Jordan Schneider: Tim, you wanted to add a requirement to make these hyperscalers take AI security more seriously before they get access to government financial help. What is the market failure here, and what are the sorts of things you think the government should add to their requirements in order to get all of these special dispensations?

Tim Fist: US AI companies are currently building models that they believe could, within just a few years, reshape the global balance of economic and military power. Consider AI systems that can autonomously carry out massive cyber attacks, automate scientific R&D processes, or serve as substitute remote workers for many kinds of jobs. If this is true, we really need to protect these systems against theft by bad actors.

It turns out that many of the security problems you need to solve are at the data center level. Protecting against sophisticated threat actors like nation-state hacking groups is both extremely difficult and expensive. If a company invests adequately in security, they risk falling behind competitors who aren’t making similar investments.

A core part of the executive order ties assistance around loans and permitting to strong security requirements. This creates a set of requirements that hyperscalers and AI companies can follow to raise the level of security protecting their critical intellectual property against these threats. By connecting it to this assistance, you transform something that would put you at a disadvantage relative to competitors into a strong commercial decision.

We outline several ideas for what this could look like. Specifically, it means finding the best existing standards and applying them across the board, developing new standards and guidance specific to the threat model for attacks on AI model weights, and providing government assistance for supply chain security, physical security for AI accelerators, background screening for personnel to protect against insider threats, and counterintelligence playbooks.

The basic idea is to create a strategic partnership between the government and the AI industry to improve security, with incentives on the other end to make it worthwhile.

Jordan Schneider: The piece that has really struck me when reading Dario’s article about his world in which America gets ahead and accelerates toward AGI faster than China, then the incentives for the Chinese government to leave these data centers alone falls to basically zero.

If you can steal the model weights, then maybe you want OpenAI and Anthropic to continue existing to make cool stuff that you can take and deploy. But if this is the technology which is to rule all technologies, you start to get into a US-Iran 2000s/2010s dynamic where stuff like Stuxnet or drone attacks become a concern. There’s water for cooling everywhere — what if there’s just a giant leak that fries all your servers?

The physical security of these tens or hundreds of billions of dollars being thrown into data centers hasn’t really been discussed much. You can see the potential future where that ends up being a critical part of what the US government and the firms themselves need to focus on for safety.

Tim Fist: I’m more optimistic about protecting models than you are, with the caveat that we need to think about the scope of things that it’s useful to protect.

To be more specific, I expect that over the next few years, the most powerful models developed by US frontier labs are going to be deployed internally first. There are three main reasons for this:

First, as capabilities grow, there will be numerous misuse concerns that labs will want to address before wide deployment.

Second, deploying internally before wider release makes a lot of technical and economic sense as you can use the model to accelerate your own R&D before releasing it more broadly.

Third, it makes sense to first train the big expensive model and then distill it down to a version that’s more economical to serve to users. This is reportedly now common practice across basically all the frontier labs.

If this is true, then protecting cutting-edge models can be done in a more favorable security environment where your attack surface is relatively smaller because you’re initially only deploying for internal use cases.

Eventually these models will likely get stolen, but protecting the bleeding edge from immediate theft is still worthwhile as it allows you to use those models to maintain your overall lead by investing your inference compute into AI research and development, and using those models to develop things like AI-powered cyber defense.

There’s some hand-waving in this theory of victory, and there are many unknowns, but seriously trying to predict this is worth it. The alternative is freely handing it over to China — putting all this money into power and chips and then giving the products freely to China to accelerate their own AI research programs.

Preventing denial of service or sabotage operations is also a worthwhile goal. I’ve seen interesting research recently about the susceptibility of current AI data centers to cheap drone strikes as well as attacks on surrounding network and energy infrastructure. I don’t have a view about how expensive this will be to defend against, but it certainly needs to be a huge part of the investments in defense.

Jordan Schneider: One thing I’ll say is that if America is going to win, it’s going to need PRC nationals working in these labs. If we’re doing FBI counterintelligence checks on every AI PhD Berkeley graduate — I’m sorry, we’re just not going to have an AI ecosystem. There’s some middle ground there, but that’s the one piece I was most skeptical of.

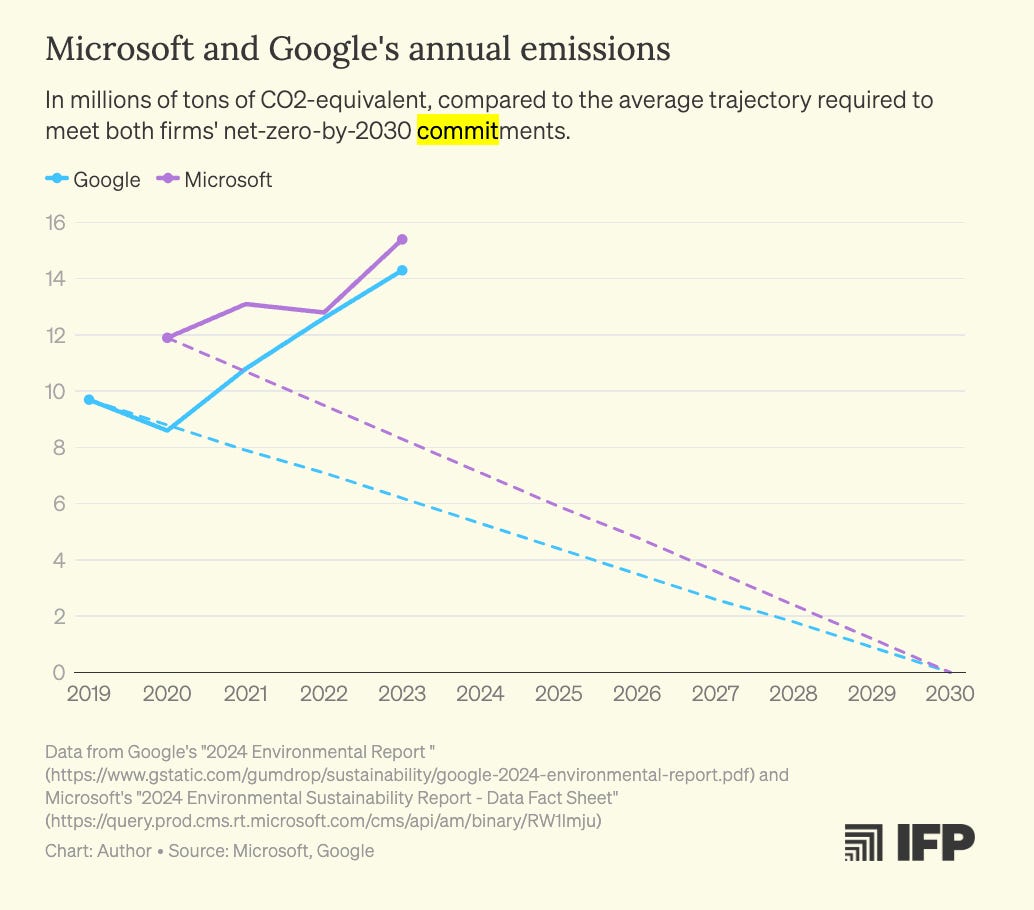

I had one random question. There was this very funny chart that Tim and Arnab had where Google, Amazon, and Microsoft all committed to being net zero by 2030, and they’re on this trend line. Then it just starts to go the wrong way once they realize they have to build tens of billions of dollars of data centers.

Do those commitments just go away? In our anti-DEI world, is there anything statutory about it? Is Blackstone going to get mad at them? What’s the forcing function here that would keep them on those trend lines, absent some really amazing geothermal breakthrough?

Arnab Datta: I wrote about this recently. The way to get more adoption of these newer technologies that are firm and emissions-free is for them to become cost competitive and quick to deploy. I don’t know how firm the commitments are from Amazon and Google or how sticky their internal social costs of carbon are.

I’m trying to think about policymakers and what we can do to get to that place — reduce those costs. These commitments are real, but they’re probably not going to stop a company from even putting a coal plant online if they know they can get AGI first. If you care about climate change and decarbonizing, our job is to figure out how to make that happen as fast as possible.

Ben Della Rocca: I agree that making these energy sources affordable is the best way to ensure they’re adopted. The related piece is making sure that the timeline to actually permit them and bring them online is efficient and fast as well.

In some cases, if clean energy technologies or emerging clean energy technologies can be brought online more quickly than other, less clean sources — if the permitting timelines are actually shorter for those technologies — that can provide strong incentives for industries such as AI to choose the faster route. There’s a large financial premium they could earn from bringing their AI models online and operational six to twelve months earlier.

Jordan Schneider: Any final thoughts, Ben?

Ben Della Rocca: There was a lot of work in the last administration to set forth actions that will address AI’s energy needs, and we’ve discussed many potential ways forward in this conversation.

A linchpin to making all of this successful is effective implementation and really prioritizing this work within federal agencies. Ensuring that people are focused on completing this work effectively, fully, and quickly, and making sure that the work starts on time and proceeds according to schedule is going to be extremely important.

Tim and Arnab, in your paper, one of your recommendations was for the White House to have an AI infrastructure czar of sorts to oversee and spearhead this work. This work is ultimately very complex and interdisciplinary. It’s not just a national security challenge — it also includes energy policy and law, and environmental permitting law. It will require strong leadership from the White House and the federal government to make sure that things happen as envisioned.

To underscore a simple but important point — the implementation side of this really matters.

> The key is finding investors willing to accept this level of uncertainty in project development. They need to be comfortable covering costs when they increase because permits take longer than expected, supply chain issues arise, or interest rates climb, making capital more expensive. All these uncertainties accumulate, making equity investors reticent to invest at a sufficient scale.

I know these investors and startups, and it's literally all regulatory uncertainty. If they felt confident the government would let the companies deploy in a timely fashion, the startups would get all the capital they want. All the non-dilutive stuff is great, and the interviewees do talk about streamlining permitting on federal lands, but the investors need to see that the startups can deploy everywhere for the business model to work. It's the same reason the tech companies themselves aren't stepping into making it happen. Until then, the feds will have to provide the capital/financing.

Mood music is a vibe