EU-China Summit: The Quiet Turning Point + Antisemites of the World Unite

This “summit of choices” may mark the turning point that brings either a more constructive dynamic in EU-China relations, or alternatively, a new chapter of stronger divergence.

Before getting into our coverage today, I wanted to remind everyone about the ChinaTalk–Manifold Markets $6,000 essay context. Here’s how it works:

Write an essay making a prediction about China. Check out our website for details on submitting your essay, which is due by January 15, 2024.

I’ll will read every essay we receive, and then highlight the best ten in a series of posts on our site, as well as on Manifund.

The authors of the first five credible essays we receive will win $100.

On February 15, we’ll announce the winner — first prize will take home $3,500, and two runners-up will receive $1,000 each (pending laws in your home country).

EU-China Summit

Grzegorz (Greg) Stec, an EU-China analyst in the Brussels office of the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), wrote today’s recap of the first in-person summit between EU and Chinese leaders in four years. In 2023, Grzegorz was selected as one of Politico’s Power 40 top policy influencers in Brussels.

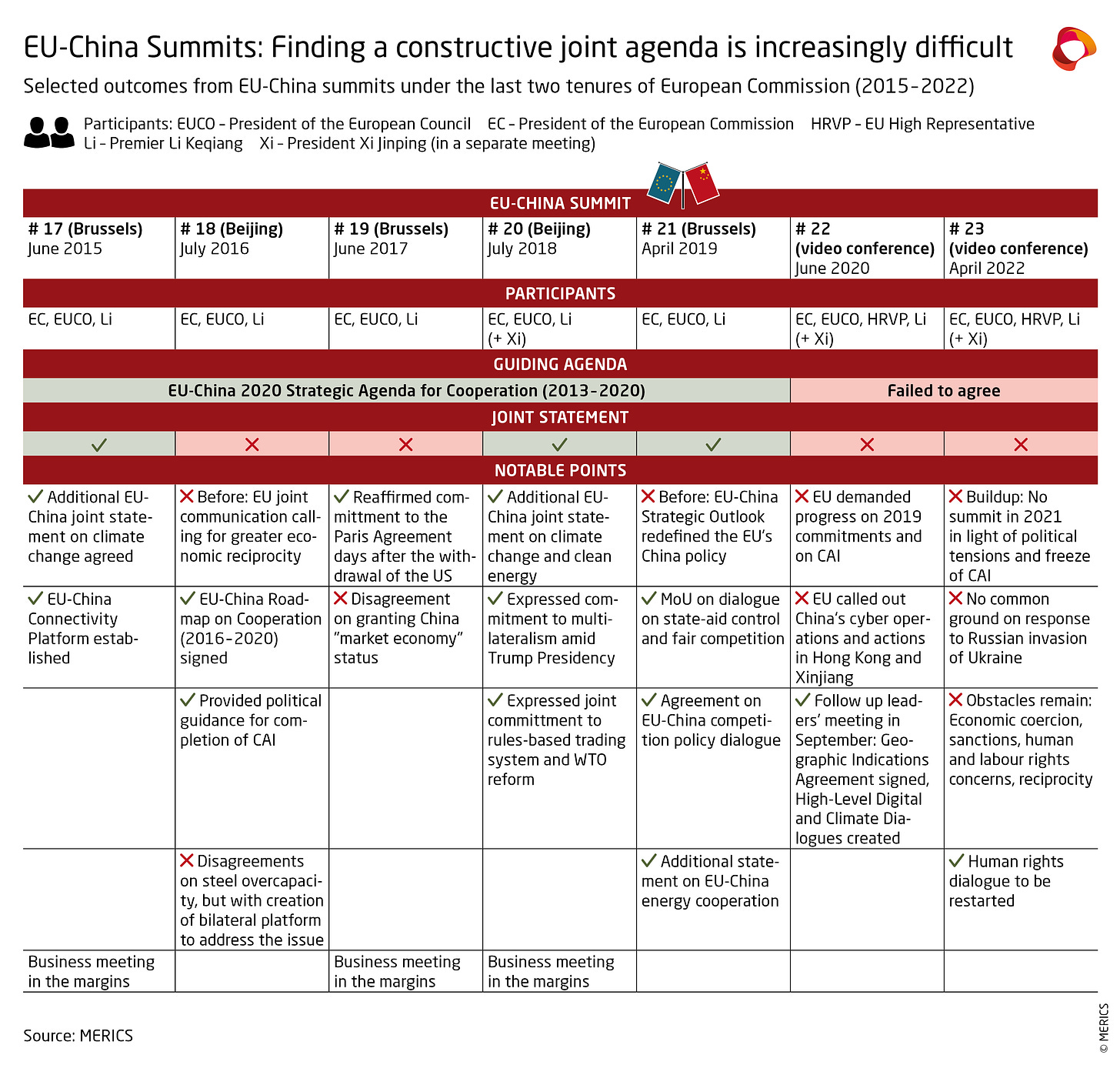

Over the last few years, EU-China summits have evolved from amicable meetings that set a cooperation agenda to pure damage-control mechanisms or platforms for direct communication between leaders. This summit was no different. And yet, we may return to it as a pivotal moment in EU-China relations.

The “summit of choices” label — as President Ursula von der Leyen dubbed the meeting during the press conference — captures well the state of EU-China relations. Brussels wants to change the relationship and address growing structural and strategic divergences. Beijing wants to prevent that change and stall the EU in its response for as long as possible. That mismatch was at full display at the summit, as shown by stark differences in the tone of post-summit readouts (Brussels; Beijing).

The tactical-level deliverables (like market access for cosmetics, medical devices, and selected agricultural products, the expansion of the Geographical Indicators list, and clarification of China’s cross-border data regulations) were pushed to Commissioner-Minister-level exchanges — leaving the summit focused on the big picture: structural and strategic divergences.

Brussels’s China agenda has four points:

Re-balancing the EU’s economic relationship with China — which implies enhancing market access, addressing Chinese subsidies, and preventing being flooded by China’s overcapacity exports (as that would distort the EU’s single-market competition);

De-risking the relationship without decoupling — which means avoiding exposure to critical vulnerabilities and weaponized dependencies, as exemplified by the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s energy blackmail following its invasion of Ukraine;

Supporting stability of the international order by getting China to adhere to international law — in the context of China as an enabler of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or tensions in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea;

Finding “islands of opportunity” for constructive engagement — on issues of common concern like climate change, international debt restructuring, or progress on specific human rights files.

Beijing, in turn, is set on pursuing strategic stalling in relations with the EU to ensure that it can:

Prevent transatlantic alignment, which could increase containment pressure (including within the NATO framework);

Prevent the EU from implementing economic security and de-risking measures which threaten to limit China’s access to the EU single market;

Prevent export controls and other measures that restrict China’s access to European tech.

Indeed, the buildup to the summit featured several Chinese official statements — including from Xi Jinping, China’s top diplomat Wang Yi 王毅, and China’s Ambassador to the EU Fu Cong 傅聪 — communicating that Beijing wants to refocus on “comprehensive strategic partnership” with the EU. Their logic is that reopening and expanding channels of communication would help reestablish trust, put aside the term “systemic rivalry” used by the EU, and alleviate the need for de-risking.

Even so, Beijing does not provide concrete proposals of how the trust could be rebuilt beyond reigniting dialogue formats, which historically have not facilitated substantial progress on issues of key concern for the EU. That shows Beijing’s limited motivation for a constructive agenda with the EU: Beijing has no further incentives for cooperation beyond preventing EU states from growing more assertive toward China. The gestures preceding the summit — such as the extension of temporary free visa schemes to five big EU countries, or publicly highlighting that the trade spat with Lithuania has been phased out — can be explained just as well by China’s desire to boost its economy domestically, its efforts to divide EU states, or relatively low-cost gestures to create goodwill without addressing the EU’s structural concerns over relations with China. Indeed, in the case of Lithuania, Beijing had arguably achieved what it wanted: its forceful response after Vilnius’s move to open a “Taiwanese Representative Office” pushed other EU capitals to think twice before doing something similar. And it was probably in China’s best interest that Brussels not test out its new Anti-Coercion Instrument by deploying it in response to Beijing’s attempts to coerce Vilnius. In other words, Beijing wasn’t going out of its way there to make pre-summit concessions.

But with the EU’s de-risking agenda and more robust economic security toolbox in place, Brussels is hoping to force Beijing to sit at the table for serious discussions. The EU is concerned about issues like distortions of the EU’s single market or support for Russia — and those discussions would require Beijing to go beyond its boilerplate win-win rhetoric which neglects the reality of growing competition and systemic rivalry between the two partners. From Brussels’s perspective, getting Beijing to respond to the EU’s concerns would ideally be achieved with limited disturbance to the bilateral relationship and without major disputes that can spillover to cooperative agenda items, such as on green-development pledges, exchanges on the EU’s emission trading system, or parts of the EU-China economic relationship not deemed as creating strategic dependencies or risks for EU’s economic security.

The ball is in Beijing’s court now — react or ignore. If it decides not to respond, the EU by now has a comprehensive toolbox to pursue de-risking. The recently opened trade investigation on Chinese electric vehicles can also be read as a message to Beijing that Brussels means business this time.

Still, for many measures — such as tightening export controls, potential outbound investment screening mechanisms, or in-depth risk assessments — Brussels needs EU member states’ buy-in. Beijing will surely redouble efforts to court European capitals; it already has a track record in that regard. Meanwhile, Beijing is likely hoping that the upcoming European elections may bring an EU leadership less committed to a de-risking agenda, or that the uncertainty created by the US elections next year will make European leaders more cautious about getting assertive with China.

It’s now up to the EU to show resolve — and for China to show whether it cares about the relationship enough to address the EU’s concerns. In that light, this “summit of choices” may mark the turning point that brings either a more constructive dynamic in EU-China relations, or alternatively, a new chapter of stronger divergence.

Beijing and Global Antisemitism

Back to Jordan here:

Lastly, I wanted to highlight a recent essay from Tuvia Gering, longtime ChinaTalk contributor, Substacker at the fantastic Discourse Power, and a reservist with the IDF now serving. I wanted to highlight his powerful essay on the international implications of the deep antisemitism laced into domestic official and elite Chinese discourse.

Thank you for sharing the Discourse Power article at the end. It was tragic to read about China's responses to this conflict. For a while it felt like Israel was a middle power capable of working with both sides. China's response feels like they are willing to ruin that relationship as part of their goal to go after America. What I can't understand is Israel is one of the few places in the world with strong semiconductor mfg abilities. It surprises me that China is so willing to destroy that relationship so that they can score ideological points against the US.