Explaining Evergrande

"Will we have another immediate round of financial stress-related news in China that extends this story beyond Evergrande itself?"

To try and make sense of the avalanche of reports on crisis-hit Chinese property giant Evergrande, I’ve put together a transcript of the latest ChinaTalk episode on the company featuring Rhodium Group director Logan Wright, with Rhodium intern Jon Sine (who also writes Non-Obvious Excavations) as co-host.

We get into:

Why is Evergrande in trouble and why does it matter?

The impact of government intervention in the real estate market

Have Chinese firms become "too big to fail"?

What chance does Beijing have of pulling this off?

Interested in meeting up in the Bay October 7-10? Shoot me a message on Twitter @jordanschnyc or respond to this email.

Rhodium is hiring for five positions, including roles focusing on corporate advisory, macroeconomics, and climate. Full details here.

Jon Sine: Could you give us an overview of what Evergrande is and its importance to the real estate sector?

Logan Wright: Evergrande is China's largest property developer, and its most indebted.

It has run into trouble largely because of the imposition of new financing controls on China's property developers, the so-called three red lines, which are based on controls of how much interest-bearing debt property developers can borrow on their balance sheets based on three existing ratios.

The firm's large debt burden has come into greater focus. It's been downgraded multiple times and there's increasing risks of a default. The other issue is that, as ever, Beijing has been very reluctant to provide support to the company so far.

Other property developers are also seeing their bonds sell off and there's been a rise in financing costs for the sector. That is feeding some of the market contagion this week globally, with concerns that this would have a broader impact on China's growth rate and on future potential growth because of the importance of the property sector to the economy.

Jon Sine: Why were the three red lines imposed in late 2020?

Logan Wright: Well, I think one issue was that Beijing has been waging this extensive war against property speculation for a long period of time.

Property has been the bubble in the Chinese economy that has not burst for the last decade.

People have been talking about it and the potential financial fragilities for over a decade at this point.

It's entered several different stages, but ultimately there has been a concerted effort in Beijing to reduce the possibility of this “gray rhino risk”, this idea that there is a problem that everyone is aware of, but it is being neglected.

That's commonly cited within Chinese government documents in association with the property sector, and there's an effort to reduce the scale of the property sector’s imprint on the economy as a result.

If you're in Beijing right now, you're probably looking at the property sector and you're saying, yes, all this construction does drive growth, does drive employment.

But the demographics of China suggest that we don't need that much new property going forward.

It does suggest that prices are so high, that households have to take on so much debt, that they can't spend as much in order to service mortgage loans for property. And that's actually weakening consumption in areas that we would actually like to encourage.

Those motives have long been active. And the three red lines was really a very extreme development reflected Beijing's efforts to control leverage within the sector in a way that other measures had failed. Previously, they had tried to restrict which lenders could actually extend credit to property developers.

Then they were targeting the borrowers and so it was a very game-changing development. They just said it doesn't matter where you get your credit. You cannot actually post a growth in interest-bearing debt unless you meet some of these three critical ratios. So that's why it was so, so important back in 2020.

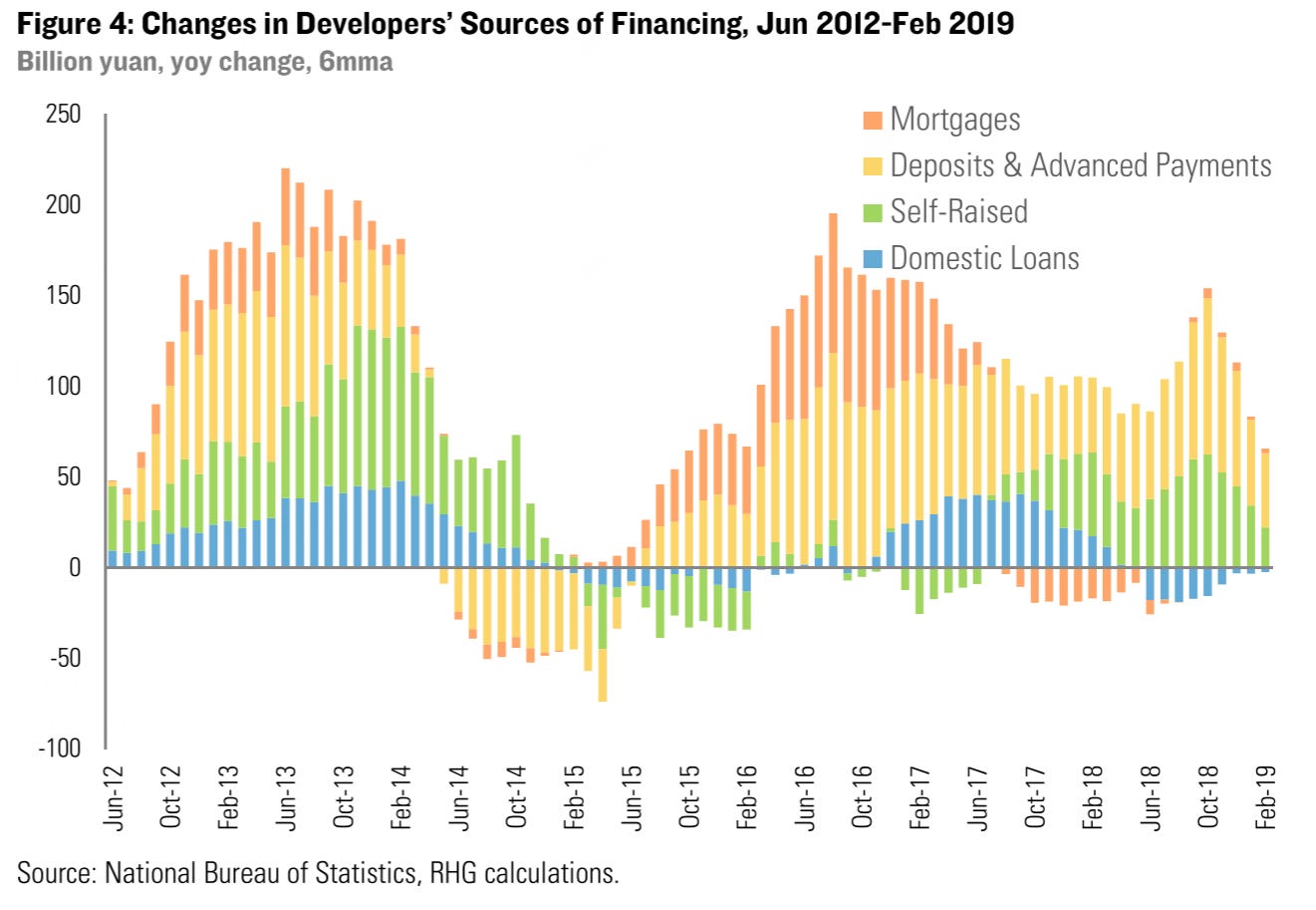

Let me just take a little step back here because there's all this focus on Evergrande itself. But it is really indicative of this broader trend in the property sector.

Overall, it's exceptional because of its size. It's not really exceptional because of its financing methods. And the story of how they got into this position is very similar to what's happened to the property sector overall.

The last time we saw a meaningful correction in the property sector in China was 2014 and early 2015. And one could argue that really should have been essentially the peak of China's property sector in the 2013-2014 period.

Right after the financial crisis, you had a huge surge in speculation of the property market, a huge surge in credit-fueled expansion in construction activities. There was a huge accumulation of inventories because Beijing was concerned even at that time about speculative purchases.

They started controlling purchases and sales in a major cities to try to keep prices under control. There was a mini correction in late 2011 in the market as monetary tightening hit and property prices declined temporarily, but most people viewed that as an opportunity to pile back.

This was the time of ghost towns and the overbuilding phase that really started in this 2010-2014 period, when most of that stock has been accumulated.

So why is it that we're still talking about property prices rising even seven years later? One factor was that policy was far more supportive toward growth at that time and toward the property sector specifically, and they deployed this mechanism called the shanty town redevelopment program.

The whole idea was there's not much demand right now for property, especially in these smaller cities, so how do we create demand for property?

And the answer is pretty simple. You relocate locate existing residents, you demolish their existing houses, which some of which were “shanty towns,” some of which were built actually much later, provide cash compensation and then they can buy houses out of existing stock.

So that process was actually pretty successful. It reduced overall inventories for about three years in the property sector and it created this artificial source of demand.

But then they basically shut it down because all the cash compensation was just fueling additional speculation and even higher prices.

You ended up seeing this dynamic where prices were rising. It was becoming even less affordable. It was becoming even less affordable than before. And the government was indirectly encouraging this speculation.

Credit growth had basically been slowing across the country, starting in late 2017. Property has benefited probably the most of any asset class in China from the expansion of credit and very rapid rates of credit ever since the global financial crisis.

Why was it that property didn't get hurt more as an asset class when credit growth started to slow meaningfully during the deleveraging campaign in late 2018?

And that's another wrinkle to this, which is that developers started relying on pre-construction sale to offset the finance that they had basically lost under the de-leveraging campaign. It sounds very crazy, but in China, it's very common for developers to basically buy land, do a little bit of initial construction, set up a sales room and then start selling houses.

Pre-construction they can collect - believe it or not - 100% of the purchase price. And people are willing to buy that early in the process simply because they think that prices will continue to rise.

It's a market that only really makes sense in an environment of very high historical investment returns, but it's also essentially a form of financing.

So rather than being bitten by deleveraging developers, we're able to offset some of the pain with this reliance upon pre-sales financing. What's the problem with that? It only adds to the inventory problem.

Jordan Schneider: We have these continuing paths where the government tries to pop this bubble or slow this curve. So what's different in September of 2021? What was the delay with the three red lines and why are we all talking about this?

Well, it was basically August and September 2020 when they started imposing this. Now we’re about a year later and many property developers have been in trouble ever since they imposed the three red lines.

Developers have been able to find an alternate source of credit all the way through this process, even when deleveraging was biting. All of a sudden this model that allowed them to continue to find access to credit, to continue building, reached a point at which it couldn't be sustained. Developers literally could not borrow any more.

If they could’’t borrow, in the future that leaves them far more dependent upon actual sales revenues to generate cash and maintain cash positions.

And therefore they needed to start discounting units and accelerating sales. Many of them became even more reliant upon pre-construction sales in this process.

You know, we've noted that China has very high homeownership rates. They're over 80% in most household finance surveys. But China has very high levels of household debt now which has increased substantially. In the last six years in particular, it's risen by $6.4 trillion since the end of 2015.

Just in terms of household debt, that's very comparable to the run-up in US household leverage in the 2003 to 2008 time frame. It may even be a bit larger depending upon how you're measuring it. And then you look at the demographics and there's just not enough young people coming in to form new households that are really going to form a foundation for demand.

The only thing that's making up the difference right now is investment-driven. Investment-driven demand is highly uneven across the country. And that's really why the three red lines have bitten and why many developers are now under pressure because the fundamentals of this market were always imbalanced.

Jon Sine: You argue that the financial system’s health is, in large part, predicated on people's perception that the government is ready, capable, and willing to step in and basically backstop, which is more or less a form of moral hazard.

Do you see these reforms as geared towards trying to undo the moral hazard in the system?

Logan Wright: To a certain extent, I think that the government is essentially trying to equalize the playing field between state-owned and private firms and say that no firm is essentially too big to fail in this context. But that's problematic.

Credit and Credibility was written about exactly this kind of moment. This is exactly why we were concerned about the rise in China's overall credit.

If you look at the decline in government credibility back in 2018, that seemed to be inevitable because Beijing didn't have an interest in protecting the riskiest and most peripheral parts of the financial system.

Essentially, that's what you've seen in the last three years: a huge rise in stated credit risk. Many institutions have defaulted since that time, including Baoshang Bank and other commercial banks, there’s been a huge rise in state-owned enterprise defaults, bond market defaults are running at roughly twice last year's pace at this point, along with multiple ratings downgrades.

(Photo: Baoshang went bankrupt last year, the first Chinese commercial bank to do so.)

So there's this significant rise in credit. You also have this interesting divide right now related to the Evergrande situation between the economic and political analysts looking at where Beijing's reaction function is and how Beijing is actually gonna respond to this stress.

The economic analysts basically say the property sector is a quarter of China's economy - higher in some estimates, lower if you just take a strict proportion of gross tax capital formation - but it's a large proportion of the economy, no matter how you think about it.

There's really no way that Beijing can do anything but support property construction over the medium term. If they are still interested in maintaining a certain pace economic growth, the consequences would be too messy. They basically have to step in.

The political analysts are saying something entirely different, which is look at how things have changed over the summer.

Look at the crackdown on tech firms. Look at the crackdown on education and tutoring firms. It doesn't look like Beijing leadership is concerned about the immediate economic consequences of their actions. They may be concerned eventually, but they're certainly not concerned enough to stop this political campaign from continuing.

And so, in that context, everyone knows that they want to control the property sector and its impact on the economy as a whole. So why should we be surprised that they are reacting very cautiously and providing only a very minimal source of support?

There's this interesting divide that's developing.

And that's exactly the moment that we were concerned about in Credit and Credibility when Dan Rosen and I wrote it back in late 2018. This was the dynamic where everyone knows that Beijing, in the event of a crisis, can provide liquidity to financial institutions.

What you don't know is if Beijing is actually trying to reform the system, and this looks like an attempt to actually introduce credit risk into the system.

At what point does the correct market pricing of credit risk spill over into broader contagion, into financial markets, and start to impact financial stability more broadly?

And I would argue that this point we're seeing right now is exactly that kind of moment where you have this debate ongoing about what exactly Beijing's reaction function is and why. There are some initial indications in the press that there are preparations by local governments to take over some Evergrande projects. But we're far short of a full plan here for an orderly workout or restructuring.

And it's unclear exactly how the financial investors will be supported. It helps that home buyers that have already committed to buying their houses. They need to have those delivered to support contractors and suppliers.

But if you are excluding any returns for equity and bond investors and for banks, then that's naturally going to have an impact on the financing environment for the sector.

And it will contribute to some of the same pressures that have been forcing developers to discount units. Reducing land sales, reducing future construction, that's really where we're starting to see some of those spillovers occur.

We've written very recently on the decline in land sales that's underway right now. It's about 43% in the hundred city data so far in September, a much deeper decline than what we saw in the 2014 cycle. And that's really the future pipeline of construction so a lot is in the balance here as we consider Beijing's reaction.

It’s exactly the kind of moment that we were flagging in Credit and Credibility, these moments where Beijing's credibility is changing are some of the most vulnerable for the state of the economy.

Jon Sine: Let me a follow on with a question posed by Adam Tooze, one of the frequent guests on ChinaTalk. He's saying it seems to be that they want to sort of orchestrate a change in the growth model. What if, along with assertion of dominance over tech and the throttling of the steel industry, this is what a shifting of economic gears looks like?

And then he goes on to chastise China watchers for saying it's striking how rarely this question is posed. So I guess two questions. Do you think what he's saying is fair and do you think they can be successful in shifting economics?

Logan Wright: I think it's fair enough to say that the markets are starting to reflect upon what it looks like for China to have a very different growth model, and one that likely features lower rates of economic growth in the future if it's less reliant upon the property sector.

I don't think it's fair to say that China watchers haven't been thinking about this. Most of the discussion over the last 15 years has been about how China could rebalance its economy away from investments and exports and toward household consumption, a process Beijing had embraced until very recently.

It's really unclear how much some of the changes that have been sparked by the census data really suggest that Beijing is still committed to economic rebalancing in that way, and to more consumption-led growth. It's at least far more difficult if you assume that the demographic headwinds are formidable in terms of the size of China’s working-age population, which has already been in decline for at least the last five years.

I think China watchers are considering these changes in the growth model. There is this debate out there about how politically feasible that is. I think there's generally more coherence right now in Beijing about the critique of China's current growth model rather than coherence around what that alternative would really look like.

Some recent articles have been talking a lot about the German economic experience, the potential for China to have many small and medium enterprises that are very high tech and at the technological frontier, but still export and manufacturing-oriented. That's interesting.

But it's far from certain that there's really a desire to get there at this point and, in general, there's more criticism out there of the tech giants and the services-led economy, and the influence they’ve had, and some of those political currents have been carried through with the events you've seen over the summer.

Jon Sine: Evergrande has been compared to Lehman quite a few times recently. What do you make of this popular comparison? Or is there another analogy that you like?

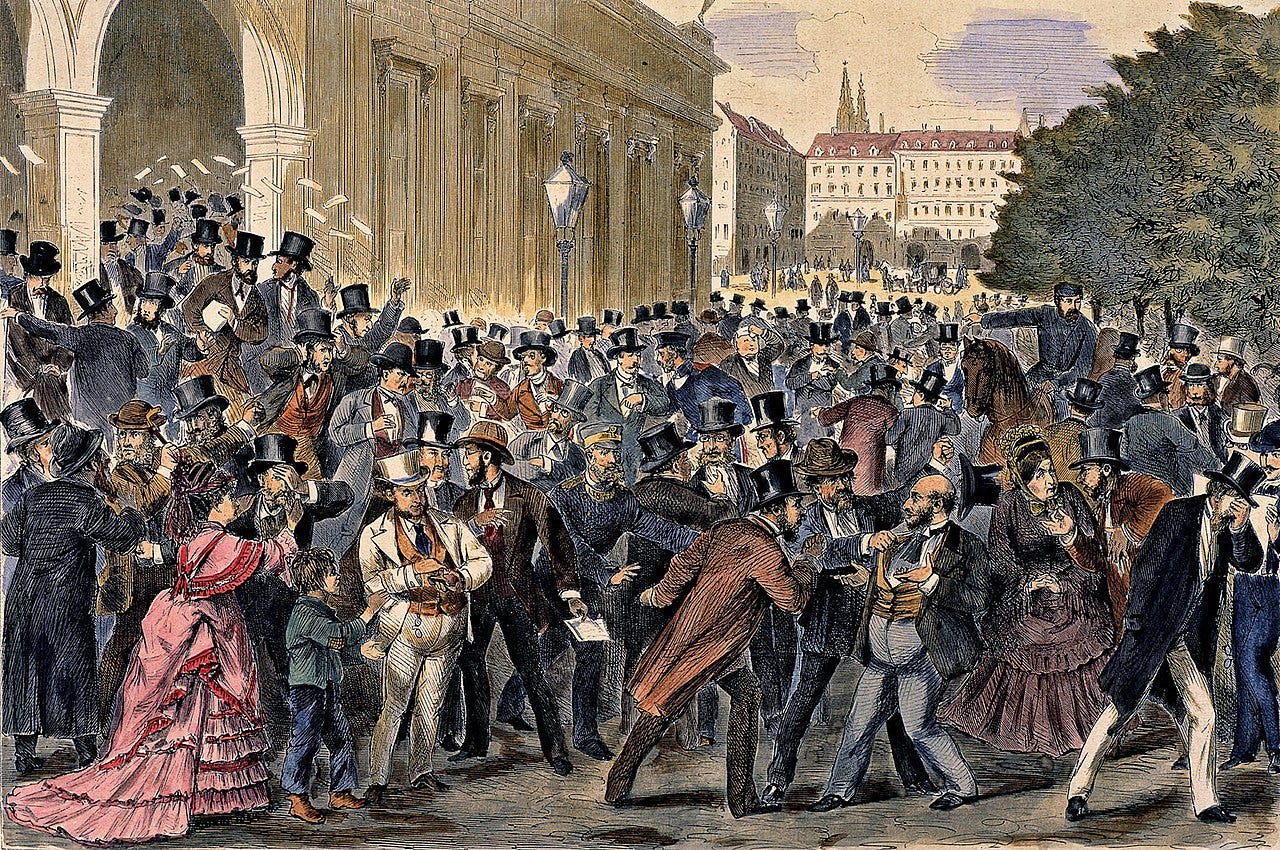

On one of my media appearances this week, I was half compelled to joke that I really think the right analogy is the Vienna Panic of 1873, just to see how people would react.

(Photo: The Panic of 1873 caused an economic depression across Europe and North America. The Vienna Stock Exchange collapsed in May of that year.)

When people are looking for these kinds of analogies, it shows just how much the narrative around China has already changed.

What we're looking for is the appropriate way to think about the magnitude of the credit-related stress that is coming, and whether that needs to be fit into a financial crisis versus an economic slowdown type.

That by itself just shows how much the narrative has shifted from an expectation that China would basically be continuing roughly 5-5.5% potential growth in the future to something that might be much lower. That's ultimately the significance of the events of this week.

Eventually concerns about Evergrande will fade from market consciousness. Markets have short attention spans naturally, and there's always a lot of news out there. But these concerns about China's property sector or the slowdown in growth or the actions against the technology companies are not really going to disappear anytime soon. We will be talking about these for quite some time.

Jordan Schneider: If everyone ends up buying into what you believe, that the current growth trajectory which China has sustained for the past few decades is ultimately unsustainable, what are the second-order impacts in Beijing, capitals around the world and global financial markets?

It will be interesting how Beijing chooses to message this. China's attached a considerable degree of credibility behind the notion of its inevitable rise. So the question then becomes, how do you message that credibly in this world in which the property sector probably doesn't feature in China's economic growth?

There needs to be an alternative model articulated for other capitals around the world. It does start to change perceptions of how they'll think about China as either a competitor or a partner.

It's hard to see exactly how that will play out at this point because it's very early days for this sort of a rethink. That's underway, but I think that is going to be the next stage of this. The other question is, will we have another immediate round of financial stress-related news in China that extends this story beyond Evergrande itself?

It is, as I mentioned, a much broader story than Evergrande itself and what we would be most concerned about is the decline in land sales, the feedback into already indebted, local government financing vehicles and the potential pressure on smaller city commercial banks that lend to those local government financing vehicles.

This is another critical part of the growth model in recent years but it has come under considerable pressure as those vehicles have become more indebted and can no longer provide the same degree of support for the economy.

Wanna host a ChinaTalk? Pitch an idea for an episode here!

Thanks for reading,

Jordan

Does the good ‘availability’ of land in China mean the zoning allows more and more sprawl? Especially around the smaller cities? I am curious to hear more about the Gov’t is paying owners for their ‘shanties’ and relocating them to vacant, new? ‘inventory. Is the new location nearby? What kind of vacancy rate facilitates this kind of gov’t program.