Export Control Drama + Anime Industrial Policy

A Trashy drama about EUV machines and how the Imperial Japanese propaganda machine helped birth the country’s animation powerhouse

A Trashy Drama About … EUV Machines?

America’s semiconductor export controls have received the C-drama treatment. Youku, an Alibaba subsidiary which began as one of China’s top streaming platforms, has produced a webdrama called 我的中国芯 The Best Chip. The Chinese title is a portmanteau combining 我的中国心 (“My Chinese Heart,” a famous 1980s patriotic song by Cheung Ming-man) and 芯片 (chips); in other words, rooting one’s beloved Chinese heart in advanced semiconductors.

The show is set in a fictional universe where, in 2020, the US banned sales of advanced DUV lithography machines to China.

A private firm is now tasked with the duty of building completely domestic-made equivalents — except that its CEO was arrested abroad while on a business trip. (Yes, that’s a not-so-subtle nod to Meng Wanzhou.)

The Head of R&D, Li Weiguo, must now defeat saboteurs, fraudulent researchers, and the lure of wealth to lead his company and country to semiconductor glory. In their attempt to make “50 watt DUV,” their one tool had some serious issues…

…and for whatever reason this machine when it blew up wasn’t in a clean room but a random office.

There’s a romance plot. Or maybe a few.

The series was set for full release on July 10, but has apparently been pushed back, my guess not due to censorship than the roasting it got in Chinese media for its absurd plot and embarrassing scientific missteps. Nevertheless, you can watch a tralier here. Youku was so embarrassed they took it down from their site.

How Walt Disney and Imperial Japan Helped Kickstart the Age of Anime

Guest post by Marko Jukic of Bismarck Analysis. They publish the Bismarck Brief, a weekly newsletter on institutions, industry, and influential individuals.

Japanese pop culture has taken over the world. Manga accounted for 76% of US comic book and graphic novel sales in 2021. It dominates in France, too, despite the country’s own rich tradition in comics (see Tintin or Asterix). The San Francisco–based anime streaming service Crunchyroll has over 120 million users worldwide as of 2022; Netflix itself feels the need to emphasize its commitment to anime, releasing dozens of its own original anime series.

True influence isn’t obvious, but taken for granted. The Super Mario Bros. Movie has grossed $1.3 billion worldwide since its April release, making it the 15th-highest-grossing film of all time, and the only one in the top-25 not based on American or British intellectual property. But Mario isn’t Italian — he’s Japanese, and he launched Nintendo into the homes of millions of children around the world in the 1980s, where it has stayed since. Along with Sony, Japan is thus still home to two out of three major game console manufacturers — the third is Microsoft and its Xbox. Over half of the top-50 best-selling video games are Japanese titles. The highest-grossing media franchise of all time isn’t Mickey Mouse, but Pokémon.

Why do people love Japanese pop culture so much? Most would give aesthetic explanations: it’s just better, cuter, or more soulful than what the rest of the world can produce. That might be true. But pop culture products are not just aesthetic or intellectual items — they are technological products that must be mass-produced by industrial institutions and exported globally. While Japanese video game success can be put down to Nintendo’s genius and Japan’s advanced industrial base, anime and manga have a more unusual history, one that brings together unlikely sources of inspiration, funding, and collaboration.

The first feature-length Japanese animated film is Momotaro: Sacred Sailors, released in 1945 — not after World War II ended, but before! The film’s titular mythical boy-hero completes military training with his cute animal friends, then invades Indonesia to oust the British. A shorter prequel in 1943 depicted Momotaro and his friends bombing Pearl Harbor. It was an unprecedented box office success in Japan, especially among children, becoming the most-viewed film in the country that year.

As Japan scholar Hikari Hori recounts in her 2018 book Promiscuous Media, these propaganda films were the result of sponsorship by the imperial Japanese military, which, for the first time in the history of Japanese animation, provided the budgets and organization necessary to compete with Walt Disney’s animated films in quality and distribution. At the time, animation was still a new, cutting-edge industry. Disney himself was on the forefront of innovation, using the transparent “cels” of celluloid for frames of animation, new techniques with camera depth, and an industrial operation of hundreds of skilled laborers to make longer and better animated films.

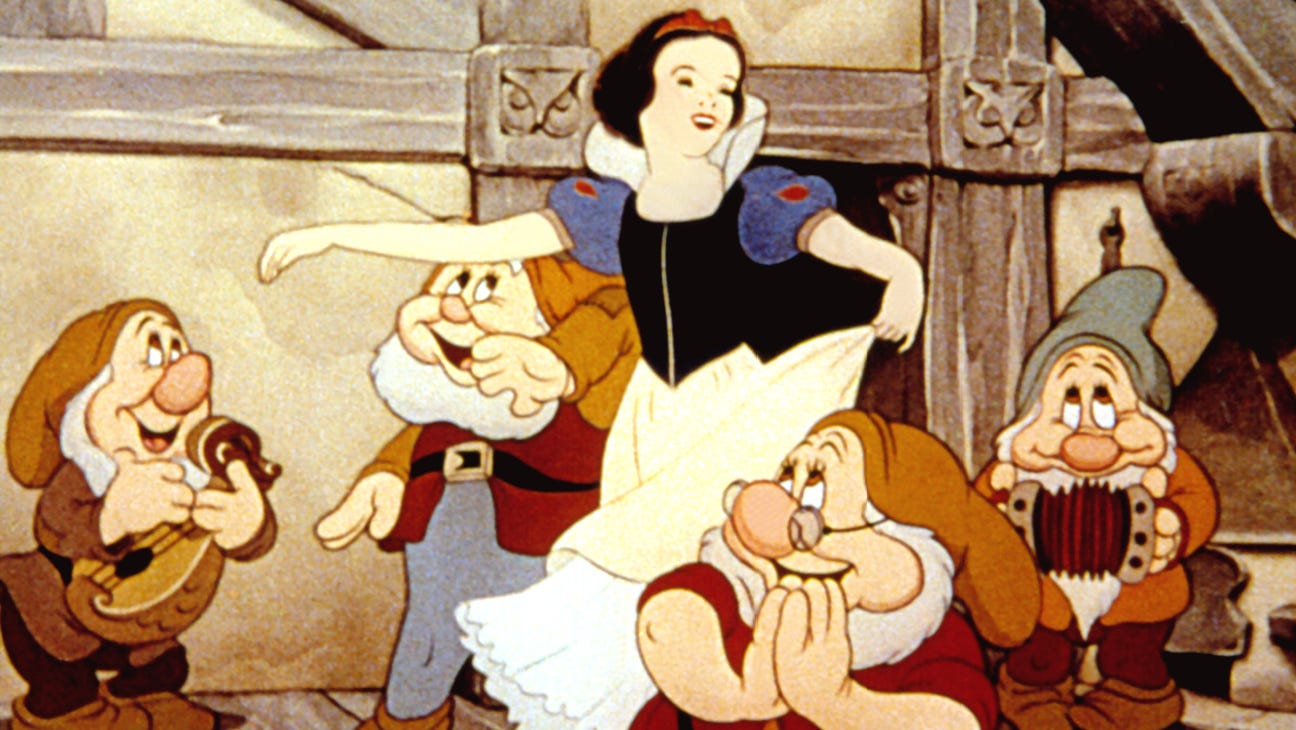

His first feature-length cel-animated film, 1937’s Snow White, was a revolutionary success with audiences worldwide, quickly becoming the highest-grossing sound film to that point. But to make it, Disney had spent nearly 100 times the baseline production budget for a short animated film. Most of Hollywood, and even his own wife and brother, thought he was crazy — until the film was released.

Meanwhile back in Japan, after the war’s end the animators who had worked on Momotaro (among them Kenzo Masaoka and Mitsuyo Seo) immediately got together to found new animation studios, imparting their skills to others. Out of this milieu emerged Toei Animation, which would produce the first anime film shown in the US, as well as Osamu Tezuka, the “godfather of manga” and creator of Astro Boy, the first anime TV series broadcast in the US. Tezuka said he was inspired to become an animator after seeing Momotaro in 1945 as a boy. Hayao Miyazaki, the award-winning anime filmmaker, also started his career at Toei.

In terms of theme and content, contemporary anime obviously has little relation to wartime Japan. But it was wartime funding that allowed Japanese animators to first investing in the “industrial upgrading” necessary to learn how to run superior Disney-style productions. These investments then paid dividends after the war, minus the Axis propaganda. Ultimately, these productions blossomed into a globally competitive cultural export industry. Anime broadcasts eventually led to the popularity of manga abroad, not the other way around. Eighty years later, we still watch mainly American or Japanese cartoons, thanks to both Walt Disney and, startlingly, Japanese wartime propaganda funding.