Export Controls, Xi's S&T Dreams, and "Technological Vassaldom"

Forcing China to rely on foreign production for the latest and greatest chips plays exactly into Xi’s fear of “technological vassaldom.”

I want to start off by clarifying a long thread I tweeted yesterday on export controls.

It was primarily a work of translation meant to capture sentiment and atmospherics of how these new regulations are playing out in China, pulling directly from this Chinese language thread.

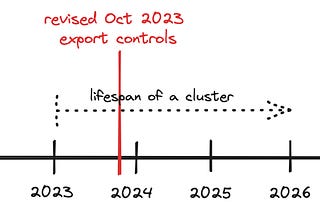

I should have made more explicit that the first dozen tweets were not my own analytical takes but rather those of @lidangzzz, a prominent tech influencer and US-based entrepreneur. In my view, they’re most interesting not for any particular legal claims (export control compliance lawyer Kevin Wolf does a great job giving a primer on what the regulations explicitly intend to do in our interview this week) but rather in how they reflect the perception in Chinese industry and likely official circles as well. In brief, these regulations prevent US firms from exporting their highest-end AI chips to China and prohibit firms and US persons from helping Chinese fabs develop leading-edge manufacturing capabilities for logic chips as well as DRAM and NAND memory.

Regardless of how narrowly Washington tries to draw the impact of these regs to allow for firms like LAM and ASML to continue working with Chinese companies on fabricating lagging edge chips, the explicit decision to try to freeze Chinese domestic manufacturing above a defined level will be perceived as a deeply provocative move, with lasting commercial, technological, and geopolitical repercussions.

Tanner Greer elaborates on the point:

In lieu of waiting for another Tanner thread, I’d like to provide a bit of that context. A great piece of literature to understand just how central S&T upgrading is to Xi’s ideology and worldview is the new book out by UCSD professor Tai Ming Cheung, Innovate to Dominate: The Rise of the Chinese Techno-Security State. He put in yeoman’s work reading through reams of dull primary sources to provide a comprehensive overview of China’s S&T plans in the Xi era.

An excerpt from the introduction:

By taking aim at semiconductors, the most high-profile strategic technology, the Biden administration, regardless of how provocative they intended to be, is throwing down a gauntlet.

Forcing China to rely on foreign production and BIS’ goodwill for the latest and greatest chips plays exactly into Xi’s fear of “technological vassaldom.” These regulations hit directly at a CCP neuralgic point.

And his key takeaways in the conclusion:

These export controls are even more dramatic of a “Sputnik moment” than what Trump delivered with Huawei’s foreign direct product rule. Even though the Administration may not have consciously timed the rollout of these regulations to the opening of the Party Congress, Chinese officials will certainly assume they have, in turn coloring their view of America’s intentions.

Whether this turns out to be the right policy call depends on too many uncertain factors to judge today. Important open questions I have include:

How is Beijing likely to respond, from both an S&T policy as well as economic coercion perspective? Does this move have the potential to kick off a tit-for-tat that materially impacts inflation and flagship US companies dependent on China like Apple and Tesla?

Are the specific technologies redlined in the regulations really critical to the balance of military power across the Taiwan strait?

Will USG be able to effectively enforce these new regulations?

Will China be able to innovate out the US technology (like they did in the space sector) and develop these semiconductor manufacturing and ultimately military capabilities? On what timeline might this happen? At what cost and with what tradeoffs? Will Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese and European companies help them?

Do the investments the US is making through the CHIPS and Science Act give America the best chance to run faster? Is more or smarter investment necessary to, as NSA Jake Sullivan said, “maintain as large of a lead as possible” in “force multipliers” in the tech ecosystem? For that matter, have we really identified all of the critical force multipliers in the first place?

Does the ‘Sullivan Tech Doctrine’ ultimately raise or lower the chances and severity of conflict in Taiwan?

These questions need the best possible answers in order to equip policymakers as they wade into uncharted waters. For a deeper exploration of how to upgrade the analysis feeding into these decisions, I’d encourage you to take a look at Carnegie Mellon professor Erica Fuchs’ paper on ‘Building the analytic capacity to support critical technology strategy’ and my essay for the EA Forum on the need for more investment in China Studies.

And finally, I’d encourage you to call your Congressperson and ask them to support the American Technology Leadership Act, which aims to solve part of this problem.

Long overdue. Change through trade has clearly failed. The west should secure all supply chains and trade preferentially with democracies

This is more or less what FDR did to provoke the Japanese into doing Pearl Harbor. I included your article and thread in my latest https://emergingmarketskeptic.substack.com/p/emerging-markets-week-october-17-2022 plus mentioned something else that I did not know: Not only do Chinese companies need to set up an internal party office when they have at least three party members working for them, securities investment funds in China now must do the same.

THAT'S A HUGE TURNOFF FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT THERE VS. INDIA, VIETNAM ETC!