Critical minerals! The world needs more of them, and the US government can help. We interviewed Arnab Datta of the think tank Employ America to talk through the ideas he put forward in his piece co-authored with Daleep Singh on “Reimagining the SPR.”

Since we recorded, Senators Hickenlooper, Graham, Coons, and Young introduced the Critical Materials Future Act to establish a pilot program at the Department of Energy (DOE) to employ an array of creative financial tools and acquisition authorities to support domestic critical material processing, refining, and recycling projects. The DOE was authorized to receive appropriations of $750 million to support at least three domestic projects, with support for each going toward at least three types of critical materials.

The legislation includes many ideas first put forward in Arnab’s piece. Three exciting provisions are worth highlighting:

It gives the Secretary of Energy a wide array of authorities to support projects including the use of forward and futures contracts, options, and other transactions as deemed necessary;

It includes flexible hiring authority to ensure that the program can hire experts from the private sector to carry out the goals of the program; and

The program would be guided by a holistic set of objectives beyond mere “stockpiling” including to provide financial stability and reduce supply chain vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the report required by the creation of the program would evaluate the use of the flexible financing authorities to alleviating challenges like market volatility, boost price transparency, and other important goals.

Co-hosting is Matt Klein who writes the excellent overshoot newsletter.

We get into:

The history and future of the strategic petroleum reserve, and how lessons from the oil market can offer insight about how to trade lithium, copper, and graphite.

How to engineer bipartisan support for moonshot policy ideas.

Lessons from a former kindergarten teacher on handling Congresspeople.

The Future of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about critical minerals, stockpiling them, and smart ways to trade them.

Arnab, for background, what is the strategic petroleum reserve, and how has it evolved over time?

Arnab Datta: The strategic petroleum reserve was established in the mid-seventies, basically in the wake of the Arab oil embargo that came out of the Yom Kippur War.

As net importers of crude oil, we realized we were very vulnerable to these types of shocks. We established a reserve, which is essentially a set of salt caverns that are dotted all over the Gulf Coast that could store crude oil for us.

At the same time that this was happening, the International Energy Agency was established, and all the members were required to keep about 20-25 days of export capability in their reserves.

At max capacity, we probably held about 600-700 million barrels of oil in there, but it hasn’t been utilized extensively. There have been a couple of geopolitical disruptions where oil was released from the SPR, for example, during the civil war in Libya in 2010-11. We’ve used it in response to natural disasters like hurricanes and things like that here, but that hasn’t really been utilized to its full extent.

When it was established, people thought about it as this asset of oil sitting in a reserve that we can release. But the SPR was created with a whole other part of its mandate to basically boost our domestic industry. If you look at the acquisition authority specifically, there are a number of goals that are outlined in that, including maximizing domestic oil production and promoting competition.

Matt Klein: Historically, Congress basically just sold oil from the SPR for money to close budget gaps.

Arnab Datta: It’s funny — if you go back to 2014, there was a big review of the SPR during the Obama administration, and that’s when the recent set of mandated sales began. They were just there to fill budget gaps.

Right now, the legal capacity limit of the SPR is a billion barrels, but the physical capacity limit is 720 million barrels. Around 2014, there was a plan to establish a new site in Alabama. They canceled that. Then they just started selling off all the oil just to whatever budget deal needed a piggy bank. Now, hopefully, more and more people are realizing that is short-sighted.

Jordan Schneider: Talk a little bit about how domestic oil production changed the whole point of this thing and what you guys have been pushing in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine.

Arnab Datta: As I said, the SPR was designed when we were net importers of crude. But in the period since the SPR was established, we became net exporters of crude and we are now the number one oil producer thanks to the shale revolution.

As we’ve become this huge exporter, our vulnerabilities have shown in other places. Refining capacity is one — we haven’t built a new large refinery with capacity over 100,000 barrels per day since 1977. Exxon Mobil Holdings recently announced that they are trying to build one in Texas. But as you can see, our vulnerability is no longer really in crude oil.

A second thing that happened during that period was financialization. The WTI contract and the Brent crude contracts were established in the eighties, and they transformed the market dramatically. They’ve made it easier for producers to attract more financing. They created a mechanism for the bottom of the market to hit less quickly in the event of a supply glut or for the top to be a bit slower in the event of a shortage. More broadly, there’s a transparent market with important pricing and investment information that’s widely available.

Coming out of the COVID pandemic and recession, we started to get really worried about the prospect of a crude oil shock causing inflation and even a potential recession. We had been looking at investment patterns in shale and seeing investment drop off, so we were worried that prices would go really high.

We started to explore different authorities that we could use to boost domestic oil production in the short term and minimize some of that price pressure.

We zeroed in on the SPR, and whether contracting authorities and acquisition authorities at the SPR could be used to provide producers with the certainty they needed to go and produce.

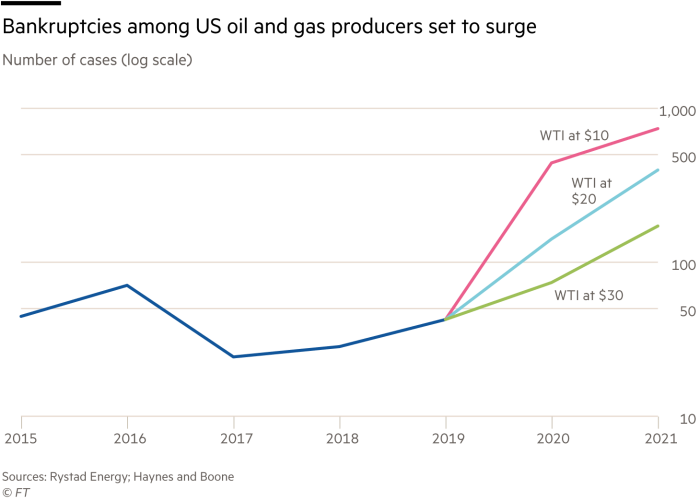

Coming out of the shale revolution in the late 2010s — prices decreased and there were a whole host of bankruptcies among shale producers at each successive price level. Thus, investments eventually started to become less sensitive to price increases.

Even as prices coming out of the Russian invasion of Ukraine hit $130, we didn’t really see a huge investment response. Why? You heard oil CEOs talking about this. They had billions of losses over the previous decade that they needed to make up, and they couldn’t justify investments to their shareholders if the price increases were going to be just a momentary blip.

We needed some mechanism essentially to get at that capital discipline problem.

Matt Klein: When oil prices went extremely low and WTI went negative, there was actually a proposal to refill the SPR specifically to essentially bail out American oil producers.

That did not happen, which probably exacerbated the supply shock problem a year or two later.

Arnab Datta: It shows you how short-sighted politicians can be on this stuff. They took the stance of “We’re not going to give a bailout to oil companies,” but the oil companies ended up profiting off of that in the end.

Matt Klein: I know a lot of the work that Employ America has published is about using the SPR for managing crude, but is there a capacity with the existing legislation of the SPR to also stockpile and trade refined products as well?

Arnab Datta: It depends on how creative you want to be with an authority. We do have smaller kinds of refined product reserves — they’re not utilized in the same sense. There are storage issues that come with storing refined products.

A lot of this is oriented around the question of how much oil price instability — both for refined products and for crude — affects exchange rate stability. We made the case that this is something worth taking seriously and accordingly, that the Exchange Stabilization Fund at Treasury should be utilized for this purpose.

Now, that’s not something that it’s typically seen as outside of the scope of some of the folks at Treasury. I understand their concerns. But outside of some of those authorities, it’s difficult to do this.

Matt Klein: You mentioned the storage issues — do you mean that refined products just literally would not be suitable to put in the salt caverns that the SPR has?

Arnab Datta: Yes, they degrade differently. To be clear, we could build facilities to store refined products. But they degrade outside very, very specific conditions. They degrade much more quickly.

Jordan Schneider: Why don’t you talk through the tension of working on this and pushing forward climate goals as well?

Arnab Datta: I’ll credit my colleagues, Skanda Amarnath and Alex Williams, for making the case that this is important for decarbonization.

When you think about the energy transition, the price volatility of crude oil is as much of a challenge as crude oil itself. There’s a tendency among folks on the further left to engage in “keep it in the ground” rhetoric.

It ignores the fact that people need oil. This is not something that’s going away overnight. We need to think about how we are managing that stable transition and making sure that EVs, for example, are price-competitive with ICE cars.

This type of flexible contracting allows you to essentially set a soft floor on prices. If prices go to $40 again, EVs become less price-competitive. Making sure that the levers of policy are being utilized towards price stability over time is important.

Matt Klein: China is another very large oil consumer, of course, and they are much less transparent, but they also have very large strategic reserves and seem to use them actively to manage prices. What your sense is of how that works?

Arnab Datta: I have some friends who are very interested in this and they share data when they can find it, which as you said, is not easy. Generally, when I see some big development that they’ve started purchasing a lot, I try to just think about it in the context of what it means for prices going forward and whether we’ve got enough supply coming on.

There have been times when some action has happened where they started purchasing and storing a bunch of refined product. There’s always a worry about what that might mean — What are they gearing up for? I just can’t get a sense of their motivations from that. I really try to look at what it means in the broader picture for the supply-demand picture.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s come back to the legislation. What is the actual contracting change?

Arnab Datta: Put simply, the DOE can now utilize forward fixed price contracts when it’s acquiring oil for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. In the past, prior to this rule change that happened at the tail end of 2022-2023, the regulation for acquisition basically said, “When acquiring oil for the SPR, DOE shall use a price index to account for fluctuations in market prices between the time of contracting and the time of delivery.”

What does this mean in practice? If I am DOE and I write a solicitation for a million barrels of oil nine months from now, the clearing price at delivery is not pre-contracted for. It’s based on the spot price of oil at that time. What that means is if you’re a producer and prices go up in that period, great, you’ve earned a little bit more money, but if prices go down, you'‘e at a loss. At the time that this practice was established, it wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. In some ways, it made sense. It was before a futures market. But now, particularly in the context of sending an investment signal, which is one reason why the DOE undertook this change. You want certainty. That’s the thing that producers need. They need certainty, particularly at the floor that they're going to be able to get a certain price.

The big change that DoE made in this regulation was changing that single sentence from “shall” to “may.” They can still do the market index pricing, but they’ve started to use fixed price forward contracts, which they’ve been engaging in for the better part of a year now.

Matt Klein: The type of oil that’s produced in the US by shale producers is meaningfully different from the type of oil that historically the US has imported and put in the caverns. Does the SPR make allowances for things like the sulfur content and viscosity? Are they aiming to specifically say, we want to support the US shale industry by stockpiling the light sweet versus the heavy sour? How is that process unfolding?

Arnab Datta: Unfortunately, their solicitations are all in sour crude right now. There’s a good reason for that - it’s what they have storage capacity for in the SPR. They do take sweet and they have stored it, but it can’t be commingled from what I understand. You basically need to keep the sour with the sour and that’s where the capacity is right now.

The other reason they tend to prefer to purchase sour is because our refining capacity is much more oriented towards sour. That’s a challenge that we still have to work through frankly.

If we’re thinking about incentivizing domestic investment, we’re really thinking about the shale patch because that has the shortest investment cycle - just nine to twelve months. We need to think about how we can maybe reorient some of our existing SPR caverns towards the sweet so that we can use it more as an investment signal that way.

Matt Klein: You mentioned you’re from Canada — the tar sands oil is very sour, right? Is there a possibility of doing some kind of cooperative arrangement with the authorities there to say, “Well you have the really sour stuff, we got the sweet stuff, so let’s work out a deal?”

Arnab Datta: It’s something I would certainly like to see. There are authorities and ways that you could do this. You could utilize the exchange authority. Whether it’s possible technically - the people who manage the SPR are really the only ones who know that.

But it’s a broader point that’s really important - because of how globalized this market is, we should be thinking more about how we can utilize allies and their resources to achieve a shared goal here.

One big development in the oil industry of the past couple of years is that the Dangote refinery in Nigeria finally got online and that’s purchasing West Texas intermediate - shale sweet crude. We do have capacity coming online that is able to take more of our shale patch product.

From Strategic Oil to Strategic Minerals

Jordan Schneider: How do the dynamics we’ve been talking about around energy map to critical minerals?

Arnab Datta: One thing that is similar is that a lot of the dynamics that you see when it comes to investment among producers are true for a lot of commodities, like copper and lithium. They tend to be characterized by these supercycles that are in some ways even more extreme. In the shale patch, you have a nine-to-twelve-month timeline from investment to production. In a lot of mining contexts, that time period can be years.

You don’t have a lot of price certainty. There is a risk that you’re going to start producing at a time when there’s too much supply already on the market and you’re not really going to get a great price for it. These are the dynamics that characterize all commodity investment. That's the challenge we really need to work with here.

There’s a tendency to under-invest, because the cost of underinvesting is suboptimal profits, while the cost of over-investing is potential bankruptcy.

You saw this after the big shale investment in the late 2010s when oil prices went down, but you also saw it in lithium. In the late 2010s, China had basically scaled back a bunch of its EV subsidies, so there was a huge supply glut of lithium on the market. You saw producers from Australia and Quebec basically go bankrupt because they couldn’t sell their product on the spot market in a way that was economical.

Jordan Schneider: All right, so what’s the answer?

Arnab Datta: Daleep Singh and I wrote an article about this in FT — this was before he rejoined the administration, but our idea was to reimagine the SPR as a strategic resilience reserve. The concept is that we have these vulnerabilities in other places with other commodities, whether it’s lithium, copper, steel — a whole host of things that we need for the energy transition, but also in refined products. Could we reimagine the SPR to basically address the similar vulnerabilities and disruptions in different markets?

Jordan Schneider: Let’s go a few levels deeper, Arnab.

Arnab Datta: It’s worth stepping back and just thinking - put simply, we’re trying to manufacture a lot of the tech needed to decarbonize here in the US - EVs, solar panels, small modular reactors. But to manufacture that stuff, we need a steady supply of a bunch of different commodities, let’s call them energy transition commodities. Things like lithium for EV batteries, graphite for casings for nuclear reactors and copper for electrification.

For many of these commodities, the US producers are reliant on a single source - China. They’re the only ones who really have developed these markets. They've designed them in a lot of ways around their own domestic goals and policy. So when we think about having our own manufacturing renaissance, basically from a risk management perspective, securing the supply chain for these commodities is a key challenge that we have to undertake.

If you’ll indulge me in going a little bit deeper on that, this issue runs from a market level all the way down to individual projects. If you think about energy transition, commodity demand is rising all over the world. But the supply is controlled by China from the raw ore, which sometimes they can control anywhere from 60% to 90%. Even more important is the refining capacity, which they often control 90% of. They really have a lot of the supply themselves.

What they can do is they can tactically strategically flood the market for these commodities, driving the price down globally. That both changes the market, but it makes it really difficult for new entrants to invest. If we’re thinking about domestic miners in the US, miners in Australia and Canada, it’s very difficult for them to invest when the current price of lithium, for example, is really low. So that makes it difficult. It also reduces the value of those assets, and it creates opportunities for China to go in and buy these distressed assets and continue that domination.

But aside from these market dynamics, the market infrastructure itself is also very dominated by China. If you take something like lithium or cobalt, the only physically cleared benchmark contracts are on the Guangzhou Futures Exchange. Basically, there’s a couple for some of them - I mean, there are ones on the LME as well. But if you’re looking to hedge, that’s where you have to go.

The existing cash-settled contracts are also imperfect. If China has a localized supply glut, it’s going to impact the price of those contracts. If you’re a lithium producer in Quebec and you’ve got a signed offtake agreement with Texas Tesla Gigafactory, the price index in your contract, which is normal practice, is highly correlated with Chinese local market supply. When their prices go down, the value of your contract with the Texas Tesla Gigafactory goes down. That makes it very difficult. It can make your project more distressed.

Stockpiling is an answer a lot of people are throwing around. It’s useful because you can give producers some of the certainty they need, but it’s not necessarily sufficient, because what we really need is market infrastructure. We need something more transparent.

Matt Klein: If China is the biggest market for physical lithium, changes in Chinese demand will affect the price of lithium, which will affect the Quebec-Texas trade — that makes sense to me. But I don’t understand why the fact the futures market is based in China would make a difference. Can you kind of walk me through that?

Arnab Datta: I should have been a bit clearer there. The fact that the physical contracts mostly exist in China is much more of - if you’re a producer looking to hedge, that’s where you have to go. That market is not necessarily the best governed or necessarily the most reliable in terms of meeting contract obligations. I’ve talked to producers who have tried to go there and use it to hedge, and they haven't had great experiences with the actual honoring of contracts. In 2019, a lot of these offtake contracts, whether they were on exchanges or not, just weren’t honored. Companies were left holding the bag.

Jordan Schneider: You had this cool riff on lessons from the Fed and this idea of crisis prevention versus crisis mitigation. Why don’t you talk a little bit about that?

Arnab Datta: This case, zooming out — the thing we’re really trying to deal with here is uncertainty. Uncertainty can come up in a bunch of different contexts. There are a lot of different market failures that can happen — agency issues, asymmetric information — but you're basically dealing with a bunch of different tail risks.

What we analogized to was the Federal Reserve. When it’s managing financial risks, it essentially has a toolkit that it can utilize to prevent crises and to mitigate them when they occur. We can’t predict everything, obviously, but if we can build a toolkit that’s capable of conducting operations in both those spaces, you can build something more resilient.

In the context of the Fed, crisis prevention looks like things like capital requirements for banks to make sure that if there’s some kind of a crisis, they can bring some equity to bear. Then there are a whole host of other bank regulations. In past crises, in 2008 and 2020, they’ve basically served as the lender of last resort. To keep liquidity in the system, they purchased distressed assets - I mean, indirectly, at least.

In the context of commodity markets, you have similar dynamics. You need to evaluate, in real time, if there is enough resilience in the system so that we’re getting the level of production we need. You can do that with things like forward price contracts, like put options. You can make sure that there’s enough incentive to produce to a certain level so that we don’t have a shortage.

But if it does occur, or if you get the other challenge, where if you get too much production, you can have the federal government step in and just start purchasing it and serving as the buyer of last resort so that those companies that did produce don’t end up going into bankruptcy. They have a place where they can still remain viable as companies by selling their product.

Matt Klein: Arnab, you said that Employ America got into this originally because you were rightly concerned about the possibility of an oil shortage leading to unwelcome inflation in ‘21 and ‘22, which was right. I’m curious, are you guys next going to cook up a plan for the Fed to trade commodities futures as the logical way of doing this?

Arnab Datta: We, in our paper, laid out a couple of ways this could go. One is you can cobble together a set of executive branch authorities to basically undertake the work necessary to do this. There’s some new offices that have been created. These are offices that potentially could be set up to evaluate markets in real time. There's a foundation that was established at the Department of Energy with a pretty wide ambit to support the Department of Energy’s work. Could they be evaluating what’s happening in lithium and copper and saying, we need to hit this vulnerability? Possibly.

Then you have a number of different funding streams, like the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations. You have the Loan Programs Office. Could they be undertaking activities? We put out a recent proposal for LPO to basically capitalize a special-purpose vehicle that would engage in the trading we’re talking about to give producers the certainty they need to go produce. It’s not a perfect version of this, but it's a pretty good one, and it’s one you can do with the authority you have.

Broadly, though, I’d love to see Congress equipping an office with the capacity in terms of staff to evaluate these challenges and vulnerabilities in real time and giving them the toolkit to actually act through market channels. Basically, to both purchase either directly with producers and tie it to capital commitments, or to just purchase on exchanges would be really useful.

Regarding our SPR intervention — what is happening now is great in terms of the fixed-price contracts, but it’s still a bit clunky. Besides the sour-not-sweet issue, it happens kind of beside the market rather than through the market. If we’re thinking about market intervention, if DoE could just directly be trading WTI contracts, that’s a more efficient channel to the market. Equipping the SPR office of the DoE to basically set up a trading account at CME and start trading this stuff would be pretty useful.

They can keep pushing for an incentive to build even more storage capacity, potentially. There are new contracts being established. There’s a new company - I mean, it’s been around for a while, but there’s a company called ABX that just launched their first contract last week or a couple of weeks ago. It’s an LNG physically cleared contract. They’re looking to really make a splash in battery metals in physical contracts, which don’t really exist outside of China right now.

Jordan Schneider: We saw this work pretty well with the CHIPS program office, but that required a new organization and 200 people coming in from outside of government who have been actively playing in these markets for their careers. Curious about your take on that, Arnab.

Arnab Datta: It’s always tough. CHIPS has done a great job. One thing I will say is just stepping back to your point about the political consensus around this — it is changing.

I speak with a lot of miners and folks in the industry — they speak to Republicans about this.

More and more Republican staffers I talk to are starting to understand, particularly because these are not functioning free markets. This is a place where another country is playing a very active role, and there is an understanding that we need to respond in kind. We can leverage our skills in building financial markets to do that.

To your point about staff capacity, when we first started doing this work, advocating for this with the SPR, there was a lot of resistance from people internally because it is very different. It’s a totally different type of contracting. It’s not something that had been done. But you also do find that over time, bureaucrats do learn how to do this stuff, and they can figure it out. Ideally, you want to set up something that has the capacity to do this - like the Fed has economists and people from the banking industry who know how to set up purchasing facilities in a crisis. You want that built in, probably, but there are also ways to get it done without that.

Jordan Schneider: One thing about the other dynamic that is a little underappreciated about this is you can attract talent to do cool stuff. This is a whole lot more exciting than whatever was happening with the Strategic Petroleum Reserve ten years ago. If you allow people sort of room to run and be creative and thoughtful and use their energy in an active way — you can attract a different type of talent.

Arnab Datta: Traders are included in this context. I’ve spoken to traders who lament the fact that Joe Biden is now the greatest oil trader of all time. It’s him and Marc Rich basically, next to each other. When you think about the necessity of doing this for public purpose and that you're not going to get a percentage of the trade on the other end of it, but you're going to execute something really cool, people get excited about that.

Matt Klein: I’m reminded of something I worked on a long time ago when I was an intern somewhere else, which is the farm subsidy system we have in this country. People obviously have a lot of issues with it in various ways. Nevertheless, there’s a pretty strong cross-partisan consensus that it's good to have a whole system of supports that are all different for different kinds of crops. It's not just one system - it’s very customized for things like whether it’s peanuts or wheat or soy or whatever.

Yet that seems like something built up over 90 years. Do you see other people thinking about this commonality, like what we can learn from that and whether that is an appropriate analogy?

Arnab Datta: It’s right. The Commodity Credit Corporation is the last of the government corporations established out of the New Deal that’s still standing. That’s because farmers rely on those tend to come from red districts. You could imagine something like that for mining districts.

One important thing is that people in that context understand that we need to be creative and have flexibility in designing different contracts for different goods, as you said. What happens in the lithium market is going to look very different than graphite.

We did a series last year on why the federal government has an interest in establishing a liquid lithium benchmark. In the context of graphite, that’s not really true, because graphite is used so differently, basically in everything, that its form and function look so different that it doesn't make sense to have this commoditized version of it.

That analogy is helpful for that point as well. It takes time to build these things. After we wrote the FT article, a lot of folks started to reach out, people from mining in the defense industry and commodities that are coming into defense with the green energy transition. Building that type of coalition, though, is something that can be done. It's just that everyone needs to see something in it for themselves.

Part of that is where you get into the contractual flexibility, the financing flexibility, so that every kind of industry can get something appropriate for them. One of the problems that we have with legislating these days is something very narrow gets constructed. It's a loan authority. Loan authorities can be great. Lending right now is helpful because the cost of capital is very expensive. But it's not the only thing. It's not the thing that's going to bring a project online necessarily, because you also need a demand piece to it. So making sure that something is built that has that flexibility is really key.

Matt Klein: Right. The demand piece is why the cost of capital is so expensive.

Arnab Datta: Exactly.

Jordan Schneider: We got the inside game. We got the outside game. We've got PDFs, we've got Financial Times articles, we got blog posts, we got private memos, we got podcasts.

How do you sort of orchestrate something like this, a relatively bipartisan, technical-ish thing into existence?

Arnab Datta: Orchestrating is very generous. I'm just incredibly lucky to work with amazing people. Skandar, our executive director, was very early in identifying this as a potential problem. It helps to be first and be good and be right early on.

The way that we approach our work here, particularly in the inside-game aspect of it, is we do a lot of work and apply a lot of rigor to make sure that what we're proposing is within the realm of possibilities, both from a legal perspective, from a policy implementation perspective, and from a political perspective. You need to evaluate all of those fears and put something forward.

I was very lucky. My first job was with Michael Bennet, who's a very thoughtful senator. My first boss was a guy named Charlie Anderson, who thought through this stuff very deeply and technically as well. So I was lucky to learn that skill from him and other people in that office. When you're thinking about balancing the different pieces, the first piece of it is really getting those details right. Everything after that can follow, but it needs to have some level of viability and rigor to it early on.

Our very first version of this was the weekend after Russia invaded Ukraine. Skander and I wrote a two-page memo that we sent to NEC and NSC outlining the contours of the original proposal, which is different than what it ended up being. Then realizing we heard some positive responses to it, we got some more negative responses to it. We tried to then think about what the public case looks like.

We need to think about how to reach every different kind of stakeholder there that might have some agency in this. We started to make that public case. Then over time, when we felt that they weren’t being responsive enough, we got a little bit harsher. Then when they were responsive, we started to ease up a bit and try to find ways to work through some of the details. You need to be nimble.

Jordan Schneider: Can you expand on making sure this is actually legal and knowing when to be mean?

Arnab Datta: On the legal side, it is common practice for the White House to suggest something to an agency and for that agency to come back and say, “This is unlawful.” That happens in every administration. It is not always true, but sometimes it is. But a lot of times it’s “This isn’t how we do this now.” There’s a conception that the way we do this now is the only legal way to do this. It's evolved over time.

You need to be able to have the confidence to say, that's not always the case. Then it just goes to how strong a legal argument you're able to craft. I'm a lawyer, and I relish the opportunity to write a legal memo laying this stuff out. Generally, in the context of the spending power, that's something where the executive branch has a pretty high amount of leeway.

When it comes to contracting, the law will define and constrain what you are able to do, but it’s rarely going to say you absolutely can’t do this. With modern-day financial contracts and lending contracts, you can usually craft something that is flexible enough to meet your goal and also comply with the law.

That’s an important thing. I’m sure there are general counsels at the Department of Energy who would disagree with my interpretations of things, but at least showing that you’ve done the work also goes a long way because you want the principal, the champion who’s pushing this forward, to at least have some of that confidence as well.

As for when to be mean, it’s going to be different for everyone. We got a bit harsher in our tone. Skander went and did some podcasts where he was a bit harsher. We put out a couple of blog posts where we were critical of Secretary Granholm and what she was saying publicly. For us, our North Star was the policy response. When we felt that they weren’t being responsive and they weren’t being correct in how they were applying this, we started to get a bit harsher. Then when they were communicating with us a bit more, we eased up.

I’ll single out a guy at NEC named Neale Mahoney, who became the champion for this and really saw it through to execution. He was someone who was very responsive and he helped us think through some of the logistical challenges.

Jordan Schneider: Resources and time are limited and you can’t do everything. As you’re thinking about trading off between another one-on-one meeting with a staffer versus writing another thing, is there a heuristic? Is it all just by feel?

Arnab Datta: I don’t know if there’s a heuristic. I will say that very quickly you run into the capacity limits of one organization and a couple of Twitter accounts who care about this thing. When it comes to the things that I’m happiest to try to invest time in and hand off, it’s some of that amplification effort.

We were really lucky to talk to and get some journalists who have influence to write about this stuff at important junctures, folks like Matt Yglesias or Robinson Meyer who really get this policy and get the importance of it. That’s something where I’ll certainly invest more time because I know that’s going to reach an audience that is helpful for me.

There are two pieces specifically about this that you can go on our website and see. One is about managing logistical risk at the SPR and the other is about auction design. I would imagine that maybe ten people read the entirety of these reports. They are long, they took days to write. I’m really proud of them. They’re really good. But that work is partly to get something out there, even though no one’s going to read it. It’s helpful for people within the administration to say this is out there now, there is an argument here that is credible, that has some work behind it. I’ll put a lot of work into that even though no one’s going to read it.

One thing I would say as a piece of advice is something I wish I did more: ask people “What does your boss read?”

Getting direct time with the boss, with the actual representative or senator, is difficult. It’s certainly difficult for outside people. The way you can do that is by getting into the publications that they read themselves.

You also need to manage bad press. Marco Rubio, for example, does care about the press that he gets on the Wall Street Journal op-ed page. In the past, there have been cases where he spent a lot of time on bills and he’s been publicly supportive of them, and then just changed a day later because one bad article came out.

The Future Of ChinaTalk and Advice for Fatherhood

Jordan Schneider: ChinaTalk is basically not going to be able to pay for my incipient child with just philanthropic support and paid subscriptions. That requires me to look for sponsors that are not foundations.

Where would you two draw the lines if you were me?

Arnab Datta: I’m highly nonjudgmental about sponsorship stuff. When I was in high school, I was the kid who just didn’t care that Wilco was in Starbucks or whatever, because I just liked Wilco and I wanted more people to listen to their music.

Your product is good and people care about it, and it’s really good that you keep doing it. Other than ethically bad companies, you should just go nuts and get what you can to keep it going.

Jordan Schneider: I love the permission slip. I’ll take it. My favorite iTunes review I’ve ever gotten is, “Jordan’s a US government shill. He gets all this money from the CIA.” I wish!

Jordan Schneider: Matt, I’m about one month out from fatherhood. What’s your advice?

Matt Klein: There’s a really good book, later adapted to a movie, called Lone Survivor. It’s about a Navy SEAL in Afghanistan. The whole first part of the book is about Navy SEAL training. At the culmination of the training, they go through something called hell week. This is when overwhelmingly most people drop out and don’t become official Navy SEALs.

The challenging part isn’t that they ask them to do anything harder than they’ve been doing. They’ve already done long runs and other tasks like being chained down in a pool to see how long you can hold your breath underwater. The hard part about hell week is that you're doing the normal stuff while being sleep-deprived for basically the entire week. They also play loud noises at you, including the sounds of crying babies.

What this means is — you are going to be a Navy SEAL soon, so that’s kind of cool.

The other thing to think about is, if it seems really hard, a lot of other people have managed to survive it. You’re in good company.

Jordan Schneider: That was the best line from the baby class you take before delivery. I was in this room with all these overachieving couples in their early thirties, and then the head nurse who was doing the class said at the end, “Some teenagers have kids. I have faith in you. It's gonna be okay.”

Arnab Datta: I used to teach kindergarten, and I had a couple of kids who had close to teenage parents. They turned out fine.

Jordan Schneider: How has your experience in a kindergarten classroom helped you in your policy entrepreneurship journey, Arnab?

Arnab Datta: Being able to address every level of immaturity or maturity is helpful, especially with Congress and people in Congress, from baby staffers to representatives and senators themselves.