Free Asia, Red China and James A Michener + Tech Policy Fellowship

A self-portrait of an evangelist for the American way

Three tech blips at the top. First off, a really exciting new DC-based early career fellowship for folks interested in S&T policy just launched.

Second, Jacob Feldgoise, Junior Fellow at Carnegie, wrote up a fantastic little script that makes scraping public submissions to US Government requests for comments far less painful than individually clicking into hundreds of web pages to download PDFs one by one. Check it out here perhaps to explore the submissions Commerce requested on how to implement the CHIPS Act.

And lastly, Rhodium’s hiring for its second tech-focused analyst! If you think that reading all those CHIPS Act submissions would make for a good time, check out the job posting here to come work with me.

The following essay is by Dylan Levi King, a writer and translator based in Tokyo. Follow him on Twitter here and check out his blog here. Edited by Callan Quinn.

Pandemic restrictions over the past two years have travel to East Asia near impossible. In a more perfect world, perhaps this would lead people to put faith in local observers. Yet that is not always easy, especially when it comes to China.

Linguistic barriers make the job harder. Political interference, such as when the government prevents Chinese scholars from attending virtual events, doesn’t help either.

There is certainly value to the accounts of outsiders on the road in foreign lands. But journalists on tour in China have also produced some of the most execrable books in the English language. And few visitors to foreign lands return with their preconceptions shaken.

As pandemic restrictions are slowly lifted and Asia begins to re-open (fingers crossed), James Michener, a travel writer active in the middle of the last century, remains a still-relevant example of how not to engage with the foreign.

One of his many books, The Voice of Asia, details his voyages through Free Asia (a term for everything outside Red China). It is now forgotten, long out of print and provides few insights into the region, but it’s worth reading as the self-portrait of a true believer in and evangelist for the American way.

In my childhood memories, James Michener books anchored sofa side stacks of Judith Krantz, Reader’s Digest, and Danielle Steele. I read his thousand-page history of Hawaii - titled Hawaii - out of desperation, marooned in my grandparents’ mobile home beside a manmade lake in Saskatchewan.

He wrote dozens of novels with similarly sprawling conceits and plain titles: Space, Poland, Texas, Alaska, Caribbean, Mexico. These books sold in the hundreds of millions. They now occupy the bottom shelves in charity thrift stores and take up space in Rubbermaid totes of paperbacks at garage sales.

Michener now stands apart from American literary history. He was the right age to join the Lost Generation in Paris, but he spent the 1920s teaching English in Pennsylvania, lecturing at Harvard, and editing social studies books for Macmillan.

After Pearl Harbor, he joined the Navy, tooling around the South Pacific as a "paper work sailor.” He began typing the draft for Tales of the South Pacific in a barracks on an island in the New Hebrides. It was a bestseller when published in 1947 but is mostly remembered now as the source material for a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical.

In the years after Tales of the South Pacific was published, there were a couple of half-hearted follow-ups, including an autobiographical coming-of-age novel and another collection of island tales. Michener spent much of that time traveling in Asia. The Voice of Asia gathers his writing about those trips.

The frontispiece boasts that he is going to visit "every Asian country (with the exception of China).” That isn’t strictly true, but he makes a good effort, writing about stops in Japan, Korea, Formosa, Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Indo-China, Burma, India, and Pakistan.

This is not an adventure. There are few colorful details about grimy hotel rooms. He is not led down alleys in search of hashish or women. There is not much poetry, either. Only women earn much beyond the flattest description.

Michener returned to Asia at a time when it was more accessible to Americans than it had ever been before. There were new frontiers in Asia for adventurous tourists, adventurers, enterprising businessmen, and every category of public and private do-gooder. Anyone with a couple of grand in disposable income could board a Pan-Am flight for a sojourn in Bangkok or Tokyo. But a trip to Asia was still serious business.

Tourists joined intelligence and information services on the front line of global engagement in combating Soviet influence. The Truman and Eisenhower administrations were enthusiastic boosters of tourism to Europe and Asia (for more on this check out Christopher Endy’s Cold War Holidays: American Tourism in France and Christina Klein’s Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961).

Michener himself takes up this mission of engagement. But he is also attempting to form his own conclusions about debates on American foreign policy toward Asia that were raging stateside. Nobody could decide who had “lost” China to communism or how to avoid a similar fate befalling other nations of Free Asia.

The foreign policy establishment was split on support for Chiang Kai-shek’s government in Taiwan and on how to deal with North Korean aggression. Was Jawaharlal Nehru going to sell out to the Soviet Union?

The central conceit of the book is that he is going to get the straight dope. He is going to listen to the voice of Free Asia. This is what Michener believes:

The most meaningless cliché used to obscure our understanding of Asians is to label them yellow hordes. They are yellow, many of them, but they are also individual human beings who can be approached by every single psychological avenue used to persuade Americans. The nation of Pakistan—as a group of such human beings—is motivated precisely by the same social, economic, political and nationalistic drives that motivate the sovereign state of Texas or the regal city of New York.

It strikes me as peculiarly American to believe that a personal survey of straight talkers is a good way to evaluate the truth. And, like all Americans, Michener believes himself to be a free thinker, unencumbered by ideological hangups, and prepared to objectively sort truth from fiction.

We see one limitation of this approach in an interview in the first section of the book. He meets a handsome demobilized soldier in Japan and asks him what he did during the war:

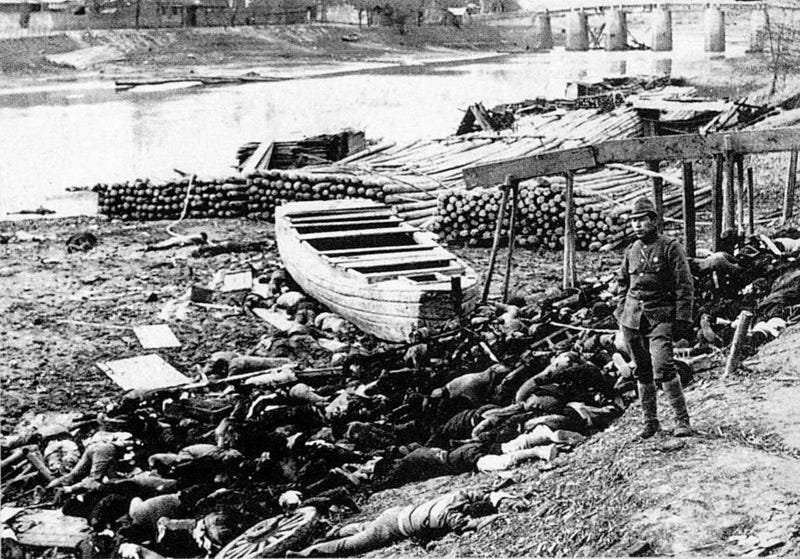

…“[W]e were sent to China and I was present at the fall of Nanking. Yes, I knew you would ask about that. I'll tell you all I know about Japanese troops in Nanking. To begin with, I'm a married man and understand both why troops sometimes run wild and why they shouldn't be allowed to do so. But all I saw myself at Nanking was one terrible incident at the river. Our soldiers herded many Chinese onto ferryboats and cut the boats loose down the river. Then our men raked them with machine guns. Did my machine guns take part in this? No, for by this time I had been promoted from machine guns to something else. I can honestly tell you I saw nothing more than that of the rape of Nanking. Did more take place? I can only tell you what I myself saw.”

A former Japanese soldier trying to settle into civilian life under American occupation might have some reason to downplay his involvement or the extent of the crimes committed. Even if we accept that he is telling the truth, he can only tell us what he himself saw. He explains his own limitations. Michener does not record him drawing any conclusions from his experiences about the postwar order.

Michener is no more trustworthy than the Japanese soldier. His investment in the Cold War project is sincere and unshakeable. But he can also only tell us what he himself saw or heard.

The conclusions that Michener makes at the end of the Japan section are disconnected from the interviews he transcribes. He says that “Japan would be unwise to tie herself so completely to a non-Asiatic power.” He says that an alliance between Japan and the United States would be alienating a billion “former Japanese enemies”—but then how would the Japanese re-integrate into an Asian order led by its former enemies?

Certainly some Chinese people in Nanjing that day must have seen the soldier’s men firing into crowds of civilians. Michener does not take them into account.

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that Michener was wrong. There are still fifty thousand American troops in Japan. The alliance has lasted. I don’t blame him for the poor predictions. But they are fairly solid proof that he wasn’t listening to the straight shooters he lined up in Japan.

He had already arrived at his own conclusions, I suspect. His Quaker upbringing must have something to do with this. He believes in the inherent goodness and sameness of all people, it’s clear. His hatred of the communists is clear, too. He hates them because they are godless and immoral. Michener’s America is the opposite of the Soviet Union.

Morality is key to Michener’s vision of an American-led postwar order. Morality is what has to guide the country’s decisions. In Korea, his antipathy toward Syngman Rhee and craven American supporters is clear, but abandoning Rhee to his fate would be morally wrong. Michener believes that everyone will come to the same conclusion and that American morality will be a counterweight to Soviet materialism:

Primarily [American intervention in Korea] saved free Asia and the entire free world. We should therefore do everything possible to tell the people of Asia why we acted as we did. ... Our free libraries, our cultural attachés, our Fulbright Fellows, and our Point Four program are doing a great deal of good. We are far from having lost Asia.

After the war, the United States must atone for its role because it is morally correct to do so; and Koreans will be won to the American anti-communist cause because of this demonstration of morality.

Morality comes up again in the section on Taiwan and his answer to the question of whether or not it is right for the Americans to support Chiang Kai-shek fighting his way back to the Mainland. His conclusions on Taiwan are refreshing. And unlike Japan and Korea, he gets it mostly right.

The China Lobby seems to have been involved somehow in his trip, since he ends up whizzing around in one of Claire Chennault's surplus C-47s, hanging out with the military, and never interviewing anyone that’s not clearly a KMT sympathizer or a recent arrival from the Mainland. He says Chiang runs the “most efficient government in Asia”:

It polices the island so that even white men can move about at night without risk of murder. It has launched an education program, prints liberal newspapers and insures just trials. Furthermore, in order to erase evil memories of initial Chinese occupation, the Government has specifically worked to protect the indigenous Taiwanese population.

However, Michener is haunted by the fact that Formosa is “perhaps the single country in the world that prays constantly for war.”

Crucially and correctly, he has doubts about Chiang’s ability to take Red China. It could be done with American support, but it would be immoral to offer that support—unless Russia “starts a war,” of course. Without that war, which Michener deems unlikely, the future for Taiwan is not pretty:

I foresee a long and silent tragedy on Formosa. Thoughts of rewinning the homeland will have to be abandoned. ... Formosa will prosper as a strange colony, half Chinese, half Taiwanese, existing under American-British protection. Other crises will arise elsewhere and Formosa will be forgotten. That is why men on Formosa pray for war. That is why Formosa is one of the worst places to build American foreign policy.

In the Hong Kong section, the last stop on the margins of Red China, an interview with “old China hand” Bill Downs returns to the theme of moral uprightness. America won the mechanical war, Downs concludes, but lost the moral war. Downs’ conclusion, however, that America should return to an isolationist foreign policy, disagrees with Michener’s call for American moral leadership. Once again, Michener is not listening.

As he travels through Singapore, Indonesia, Indo-China, Burma, and India, Michener’s relative lack of expertise becomes more obvious. He spends a lot of time trying to figure out whether his interviewees support communism.

But he must have gotten something out of these interviews, because he generally concludes that these places were left a horrible mess by their respective colonial governors, and America ought to support friendly nationalists, pan-Islamists, and agrarian reformers before the Soviet Union can steer them down the road to tyranny.

The book’s conclusion has some general rules for a reader hoping to understand Asia. They are good, if not particularly revolutionary. He counsels empathy and forgetting stereotypes.

But then he admits something to us: many of the people he talked to found him absurd. His blind defense of the American way struck interviewees as absurd or insulting. The question he faced most often in Asia was this: "How can you justify your treatment of the Negro?"

Michener has told us again and again how American morality will carry the day. But he seems unprepared to face the interrogation of skeptics.

As an unnamed “Asian” hammers him on race relations, he points lamely to Jackie Robinson and Ralph Bunche as examples of African-Americans defending America "for its treatment of Negroes."

When the topic of the FBI investigating American intellectuals comes up, the response reads as parody:

Asian: But the F.B.I. and the Gestapo are after the same thing, aren't they? Crushing all liberal ideas.

I: Will you try to understand what I am going to say? We have reason to think that communist Russia is determined to destroy us. We have found spies hiding among us. In high places. We have asked the F.B.I. to protect us.

Michener is dismayed to report that his interlocutors were rarely or never persuaded. Here, the central conceit is undercut again. There is no attempt to figure out why people on the other side of the world would be suspicious of the American way.

We read the writers that the FBI was protecting Michener from, like Agnes Smedley and Edgar Snow. Unlike their books, The Voice of Asia could have been written without leaving the United States. That is the only enduring value of it: it holds up a mirror to the American observer of Asia. It’s a challenge to escape the same prejudices.

I enjoy putting ChinaTalk together. I hope you find it interesting and am delighted that it goes out free to eight thousand readers.

But, assembling all this material takes a lot of work, and I pay my contributors and editor. Right now, less than 1% of its readers support ChinaTalk financially.

If you appreciate the content, please consider signing up for a paying subscription. You will be supporting the mission of bringing forward analysis driven by Chinese-language sources and elevating the next generation of analysts, all the while earning some priceless karma and access to an ad-free feed!