Gallagher, Tweets of the Week, Weibo Doom Scroll

Plus ASML, AI Pork, and KFC for Chinese New Year

Last week, Rep. Mike Gallagher announced he wouldn’t be seeking re-election. It’s a shame to see someone who’s sharp, mission-oriented, and not allergic to bipartisanship call time on his service in the legislature.

In this podcast episode with Philip Wallach last year, I dove into the history of the legislative branch. We closed by exploring some potential paths for Congress to flourish once again. But at a bare minimum, Congress needs to be able to attract and retain talent, both on the staff and principal level.

More than the money, travel, and time spent dialing for dollars is the inability of legislators today to pass big bills. If Congress were on the verge of an update to the National Security Act or Goldwater–Nichols Act to better align the bureaucracies to twenty-first-century great power competition, I got a feeling Gallagher would have stuck it out a few more cycles.

In my interview with the Representative last fall, the most depressing bit was when I asked him what he’d like to improve on. Gallagher’s response:

I wish I were better at speaking extemporaneously, and I keep thinking I’m going to wake up and that’s going to be a skill I have…As much as I crapped on the soundbite culture and how TV rewards the black-and-white analysis, you do have to do it. I think I’ve grudgingly accepted the fact that, in order to be successful, I have to engage on TV.

It would be nice if we lived in a system where players could advance by means other than polishing a skillset best left in high school extemp debate. For the US to compete, it needs a functioning legislature. The Hill is overdue for structural changes to realign legislators’ incentives away from viral hits and toward ambitious bipartisan bills. Below, I’m re-running an excerpt from our interview where he lays out one credible pathway there.

All that said, it’s a little absurd to write a requiem for a guy who’s 39 and will be back in the mix before too long. To steal a line from David Alder, he’s got a whole 40 years to run for president!

How Rep. Gallagher Would Fix Congress and Beat China

I went down to DC to interview Representative Mike Gallagher (R-WI) to discuss his own view of the larger dysfunction in Congress, his role as Chairman of the Select Committee on China, and how his background in military, intelligence, and academia shape his approach to his work. Lightly edited transcript below, or if you’d prefer, feel free to listen or watch.

Why Is Congress So Broken?

Jordan Schneider: How broken is the legislative branch? And on what axes?

Mike Gallagher: As an impetuous freshman in 2018, I wrote an article in The Atlantic talking about how broken Congress was. The Speaker of the House at the time, who was from Wisconsin [Paul Ryan], did not appreciate that article.

The fundamental problem, as I see it, is that the legislature is weak. It is incredibly weak.

If you read the Federalist Papers, the framers feared that the legislature would indeed become the opposite — too strong — and that it would suck everything into its impetuous vortex. They could not have foreseen a scenario in which power-hungry and ambitious members of Congress would willingly cede their constitutional authority to the executive branch. So if there is a cancer eating away at our Constitution and the body politic, it’s that: it’s Congress’s systematic surrender of power to the executive branch, which makes government less accountable.

You have unelected bureaucrats wielding powers that should be reserved for members of Congress, and I think it makes the American people more disillusioned. That is my diagnosis of the problem.

Now, what has made that possible? When the Watergate babies came in the 1970s, they saw over-empowered and corrupt committee chairs in Congress, and so they sought — in a well-intentioned way — to clean that up. But practically, they ended up transferring a lot of power to leadership. You had the creation of the Steering Committee at that time, and then a series of legislation — the Emergencies Act, the Budget Empowerment and Control Act, the War Powers Resolution — which again were intended to reclaim Congressional power but did the exact opposite.

Republicans took control in the 1990s, trying to do the same thing, but practically transferred more power to the Speaker.

Right now, we’ve arrived at a moment where power in an increasingly powerless institution is concentrated at the very top — which makes members less likely to have any loyalty to the institution, because they’re not rewarded for channeling their energy and ambition into their committee work. They’re rewarded for channeling it into Twitter or X (or whatever it’s called now) and cable news.

We’ve turned Congress functionally into a green room for Fox News and MSNBC. To me, that is the fundamental problem in Congress right now.

Jordan Schneider: Philip Wallach plotted two axes of change over the past hundred years. You talked about one of them, which is the committee versus leadership axis.

Mike Gallagher: So he agrees with me! He wrote a whole book saying that he agrees with me…

Jordan Schneider: He has another point, which is that there’s also a kind of pendulum, which you’ve seen over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first century, of Congress investing in itself and the level of professionalization — going from having basically no staff to lots of staff in the 1970s and 1990s and then tighter limits on staff budgets coming out of the 1990s. I’m curious to what extent you agree.

Mike Gallagher: With the caveat that I have not yet read Wallach’s book, which I would love to: though I am now married to national security in general and US-China competition in particular, my mistress remains Congressional reform, and I occasionally return to it. I think that’s true.

The best example and most recent example is in the 1990s. One of the Gingrich reforms was to get rid of the Office of Technical Assessments. We tried to revive that. We had a vote on that two years ago; it didn’t go anywhere. But that’s one example of the trend that Wallach points out.

I would offer a third axis, too — or maybe it’s a subset of one of these — which is that there’s a divide within Congress that most people don’t understand: the divide between authorizers and appropriators.

Authorizers basically tell agencies what they can and can’t do; they do policy — whereas the appropriators actually give money to the agencies to do things.

Now, functionally, most authorizers don’t authorize. We have many executive-branch agencies that are operating in the absence of an authorization, and appropriators increasingly authorize appropriations bills. So that divide — which dates back to the early 1800s when John Quincy Adams was a member — has been a source of incredible dysfunction. We combined the committees in the late 1800s and then separated them again in the 1920s (I believe).

But my view is that you need to make the Appropriations Committee subcommittees on each standing committee and then better align those committees with the executive-branch agencies that they oversee. And by the way, make oversight not its own committee, but rather a subcommittee of these committees that actually do meaningful work. Then you solve the problem of members of Congress spending all their time fundraising or bashing people online because they have a productive outlet for their efforts.

Jordan Schneider: So why don’t things like this happen?

Mike Gallagher: That is a great question. If you look at the last round of serious reform, there was a super committee — Senate and House — on legislative reorganization in 1993. If you read the postmortems of it, they conclude that none of the reforms were enacted because of existing committee chairs not wanting to give up their power. It is the people that have power right now that obviously are loath to give it up.

I also think there’s another thing going on: Congress has absolved itself of responsibility. In the scenario we live in now, members of Congress can blame the executive branch or write a letter to the executive branch asking it to do something that Congress theoretically has the authority to do. It’s actually useful if you care only about getting reelected, because you can just criticize without owning anything. So we’ve gotten lazy as a legislature.

I would add one more thing.

In my own view, we’ve strayed away from the model of the citizen-legislator. That intent of the Framers where you’d serve for a season and then you’d go home is no longer the norm. Now politics has become a career, and fundraising has become the overwhelming activity in that career.

The only thing I can think of to fix that is term limits. I know people have divided views on that, but I think it would actually help.

Bringing Back a Fan Favorite—Tweets of the Week

Last year on ChinaTalk, we published an epic breakdown of BIS’s new export controls from a thirty-year lithography veteran.

Litho World & Commerce: Lost in Translation?

Today’s breakdown is authored by “Lithos Graphien,” an anonymous contributor with decades of experience in the chip industry. Special thanks to Arrian Ebrahimi of Chip Capitols for his edits. Jordan is in LA next week and holding a meetup! Register here

Our main takeaway — that the regulations would force ASML to stop shipping the 1970i and 1980Di to China — was borne out this week in ASML’s annual report.

I loved this thread from John Sullivan on how the Wire riffs on the Warring States era.

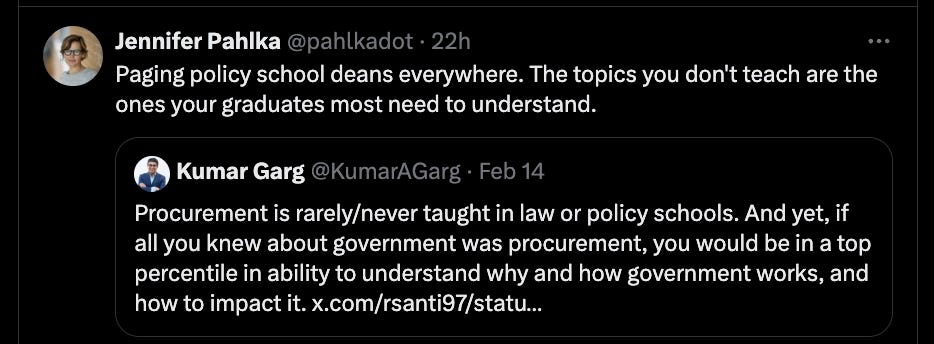

The tweet below is in reference to the excellent interview Santi Ruiz conducted with Rick Dunn, the man who brought Other Transaction Authority to DARPA. Procurement and HR dark magic are the two areas where effective senior leaders in government seem to end up spending all their time.

I’d encourage you to check out Lennart et al’s new paper on how the potential for compute controls to impact global AI governance.

Riding a Waymo in Phoenix last summer was better than any roller coaster for the sheer thrill of having a car robot drive me around (took my breath away even more dramatically than Apple Vision Pro!). Going back to Lyfts afterward, I was much more aware of just how dangerous human drivers can be. If you are in SF, Santa Monica, or Phoenix, I would highly, highly recommend taking a ride.

Weibo Doom Scroll

This week I’m excited to announce a strategic partnership with Weibo Doom Scroll, a fantastic Substack that for the past year has been putting out daily translations and commentary on all of Weibo’s most surreal and revealing happenings. We’ll be pulling from Moly’s newsletter for a weekly best-of on Fridays, where we post ChinaTalk’s favorite excerpts.

A TikTok video of Lizhuang pork 李庄白肉, famous for being “bigger than your face, thinner than paper”:

The comment section here is filled with bots saying, “We need to support high-quality content!”

And someone comments, “And yet I, as a language prediction model, cannot taste food.”

A blogger recommends various YouTube channels that explain concepts far better than his university professors, including Ben Lambert, Vsauce, Minute Physics, Steve Kaufmann, Professor Dave Explains, etc.

Comments say, “Yeah, but how do I get over the Wall?”

“And these uploaders are usually Indians.”

“Anyone cover primary school maths?”

“If you give a civil servant 10 million RMB, would they agree to quit?” I’ve asked this question to a lot of civil servants in a lot of different cities.

When I asked civil servants in small towns in the midwest, most of them are willing to quit for 10 million RMB. Even civil servants in small town Shandong are willing to consider quitting for 10 million.

But if you ask civil servants in big cities like Shenzhen, Nanjing, or Hangzhou, even if they’re just bottom-level employees, very few are willing to quit.

The treatment that civil servants get in different cities in China can be drastically different. For civil servants in small towns in the midwest, they make only about 60-80k a year if you count all the benefits. But in economically prosperous areas on the east coast, civil servants can make more than 200k a year.

10 million can lure in people who make 60k a year — but it’s a lot harder to lure people who make 200k a year.

Comments say, “You post a lot of bullshit every day. Have you ever made 10 million RMB? Do you not have a concept of money?”

“If you put 10 million in CDs, you could make over 300k a year.”

“You can’t just count a civil servant’s income while they’re working, you gotta count their retirement benefits, too.”

A lot of people blame Jiangxi’s high bride prices on sexism. I mean, that’s definitely a part of the reason, but I don’t think it’s the core.

The best example I have is Guangdong, which is just as sexist as Jiangxi, with just a skewed birth gender imbalance — but they have very low bride prices.

The main reason Jiangxi has high bride prices is because of economy and geography.

All the surrounding states have much better economic development than Jiangxi, causing large amounts of young women to flow outward. So the poorer an area is, the less women it has, and the higher the bride price.

Anywhere in China with high bride prices follows the same logic.

Comments say, “I think it has more to do with tradition. Anhui’s economy is pretty crappy, too, but it doesn’t have high bride price.”

“As someone from Jiangxi who’s worked many years in Guangdong, I think these two regions have different types of sexism. In Jiangxi, people actually abort girls. Most families have an older sister and a younger brother, or two brothers. But in Guangdong, people don’t usually get abortions. They admire having many children, both boys and girls, and just have big families.”

“In Fujian, it’s the girls who pay the dowry, and nobody ever brings it up.”

Has anyone discovered these three weird phenomena? Once our parents’ generation is too old to make New Year’s Eve dinners, then would we do away with Chinese New Year entirely?

For kids born after 1990s or 2000s or even later, too few of them know how to make a ton of dishes. Watching my mom steam and stew and cook, I just feel like a giant baby. I can’t even bring myself to make some egg-fried rice because I think it’s too much of a hassle — much less put on a feast for the whole family. Maybe our increased standard of living has made us lose a lot of culture and customs.

Unsurprisingly, a lot of people are spending their New Year’s Eve dinners in restaurants, to the point that you can’t get a reservation anywhere. After all, New Year’s Eve dinners make sense only in a rural village. When you’re stuck in a studio apartment in the big city, the vibe just isn’t great. Even if you have a nice penthouse or a mansion, nothing compares to making a huge banquet and having the whole village come over, where everyone is one big family.

There’s no sound of fireworks anymore. Back in the day, first thing in the morning, you’d wake up to the sound of fireworks, getting rid of the old year, welcoming the new year. Now, it’s quiet, and all the streets are empty. People are just eating for the sake of eating, and then each leaving their own way. And by the second or third day, everyone’s back to talking about work. This kind of Spring Festival is more like checking an item off of your list, than actually enjoying the holidays.

I don’t know if anyone else has noticed these phenomena. I don’t know if we’ve changed or if life has changed. Now, I don’t even want to visit my relatives for New Year’s, when that used to be what I looked forward to the most when I was little.

Comments say, “The person who cooks has way too much work heaped on them. Everyone else can just chat and have fun and sit around. Now, nobody wants to do it anymore. Everyone eats outside now. I hate having a table of people drinking and eating and chatting, and one person in the kitchen forced to serve them all.”

“New Year’s is just Labor Day for women.”

“Ate hotpot for New Year’s Eve and KFC for New Year’s proper. It’s not bad — I think I might make a tradition out of this.”