One of the biggest innovations in China’s fight against coronavirus is the “QR health code.” In early February, Alibaba helped the Hangzhou municipality stand up a trial app. The idea was to use big data to help monitor control the virus’ spread individual by individual so that communities could reopen more safely. The company and provincial governments across China were able to stand up the app nationwide within a few weeks.

Those with green codes were able to travel freely. Yellow codes were supposed to self-quarantine for a week, while red codes were obligated to spend two weeks at home. Once up and running, the app allowed millions to safely leave lockdown.

QR health codes use opaque algorithms and data sources to make judgments about the infection risk of its users. The account below—translated and published with permission—provides the most detail we’ve seen about how the app was made and how it works.

The story below demonstrates the strength of China’s blurred lines between state and corporation, with Alibaba employees racing to build state systems within days—and reveals, at its conclusion, a remarkable optimism about our surveilled future. Later this week I’ll publish a handful of Chinese voices raising more skepticism.

So, why doesn’t America have this yet?

First off, there are privacy concerns. I can’t imagine the data sharing this program needs passing muster under California’s regime.

Equally important, America’s lockdown isn’t enforced nearly as strictly as China’s was. Even if you have a red QR code (which all of New York City would have given using China’s QR health code algorithm), under our current policy you’d still be allowed to go out. QR health codes were initially welcomed in China as a way to loosen restrictions and organize an ad-hoc system of population control where each housing block came up with their own mobility rules.

In contrast, any sort of contract tracing efforts in the US would likely make the rules tighter. That said, maybe this can turn into a sort of requirement for more risky areas like gyms, nightclubs, and nursing homes, but unless this is either government policy or something demanded by the public at large, I’d be very surprised if it gains traction in the states.

Why are American tech firms not at the forefront of this and other anti-coronavirus initiatives? Dan Grover argues the incentives don’t quite align for America’s tech giants like they did in China since they don’t have a straightforward path to cash in on these sorts of initiatives. Soon after Alibaba stood up its health QR code regime, Tencent rolled out its own version, and the two began competing across the country for health QR code ‘market share.’ Ali and Tencent then used their QR heath codes alongside other features like maps of health clinics to promote their telemedicine verticals.

The translation below appeared in Technode.

Stick around at the end of the email for ‘Best China Tweets of the Week’ and an analysis contest of an impromptu Xi speech for the chance to win $100.

The Health Code’s ‘Long March’

Written by Yun Xi, edited by ‘Ferocious Bro’

Published on the Hangzhou Engineer Crew official account, April 3.

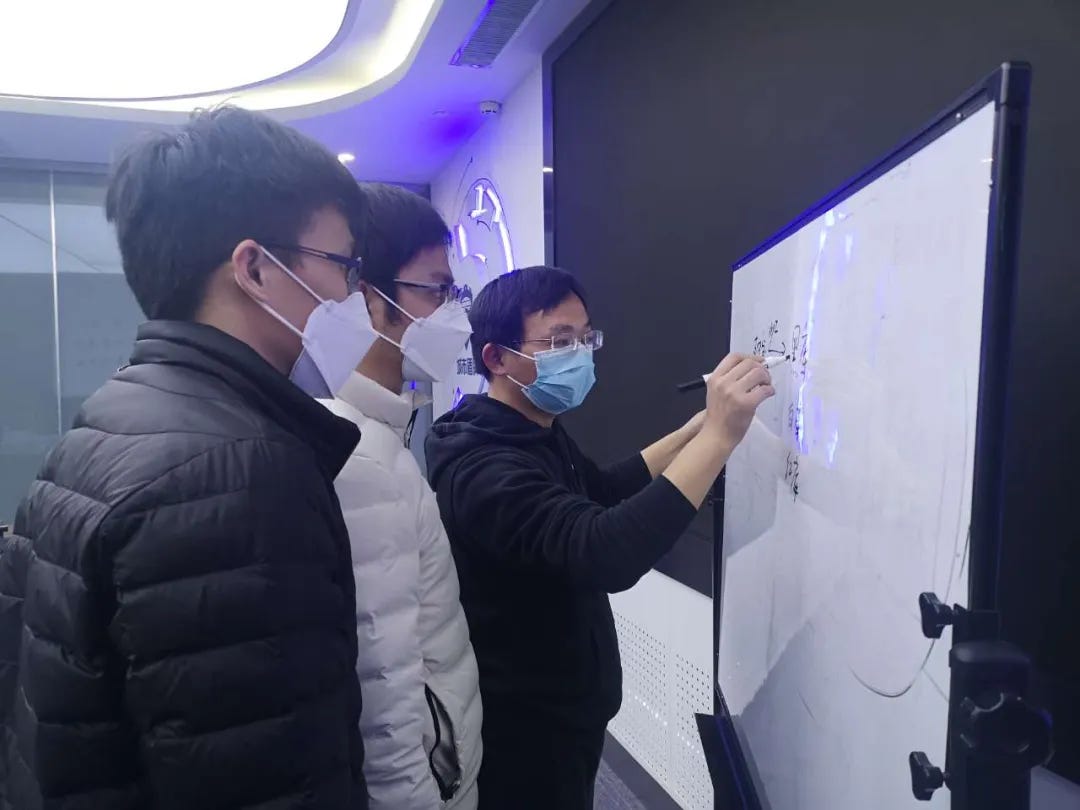

On Feb. 3, after Hangzhou had implemented strict quarantine measures as one of the first areas in Zhejiang province hit by the epidemic, the city’s Yuhang district organized Ali Cloud, DingTalk, and Alipay to form a virtual online team to urgently develop the earlier version of Health Code.

On Feb. 6, Hangzhou Municipal Party Secretary Zhou Jiangyong made a proposal at an important meeting: in order to help enterprises to resume work, the city should play to advantages of its digital economy. He proposed to establish a unified digital declaration platform, including personal electronic health codes and timely data sharing.

The Party Secretary wanted to roll out the code the next day.

Relevant departments in Hangzhou as well as within Alibaba worked overtime overnight to finalize the business logic map.

After a sleepless day of development, on Feb. 8, the enterprise employee health code was launched. The development team soon became the Hangzhou health code project team, and more government departments and technical personnel were transferred to the site.

In the early morning of Feb. 7, Yuhang District’s system, known as “Yuhang Green Code,” was officially launched. 269,000 people entered their information within 24 hours.

On Feb. 13, Ali Cloud senior technical expert Li Haolong wrote a pledge to get a Zhejiang health code online within 48 hours.

On Feb. 20, Li Kai, head of Ali Cloud digital government in Hubei province, received a list of developers who were stranded in Hubei—more than 150 people.

He used half a day to set up a virtual online group of more than 70 people, their task: in three days, to create a health code system for Hubei.

By then, the number of confirmed cases in Hubei had exceeded 60,000. Unlike other provinces and cities, which primarily use red codes to find out who to isolate, in Hubei the idea was to figure out who could go outside.

The epidemic situation in Hubei province is changing from moment to moment, so the government kept changing the requirements for the algorithm. Therefore, an entirely different algorithm from Zhejiang had to be developed.

Hubei was already divided into high, medium, and low risk areas. Within 4 hours, the team had an algorithm for the low-risk areas; within 12, for medium. For high-risk areas, they didn’t develop a general algorithm, instead focusing on covering essential workers by building a white list. People with unexplained fevers were placed on red code if they were in Wuhan; in the rest of Hubei, they got no code at all for the time being.

These problems were just the tip of the iceberg.

‘I have a sword hanging over my head’

The team started with only four people, and the complexity and accuracy of the algorithm increased exponentially, Li said.

There is no doubt that close contacts such as confirmed cases and their spouses had to be issued red codes.

“The most complicated are the atypical situations, such as driving through Hubei but sleeping in your car, or taking a bullet train through Hubei…” Ali cloud data intelligence team product expert, code engine product manager Ding Xianshu said.

“The most complicated cases to evaluate are the atypical one, such as driving through Hubei without a stop on the road, or sleeping on the road for one night, or taking abullet train through hubei, and further subdivision. Or if there’s are suspected confirmed cases in an apartment complex, do you have to put everyone in the complex on a red code?” asked Ding Xianshu, Ali cloud data intelligence team product expert and code engine product manager.

The code must also adapt to changes as rules are updated every day, changing how people visited and underwent temperature checks in public places, pharmacies, supermarkets, intersections.

At one point, project leader Li did not sleep for 48 hours. The calls kept pouring in and his lungs were clogged.

Everyone told Li to rest, but he refused. Someone complained to HR, and several colleagues forced him back into the car and sent him home.

Arriving home early in the morning, Li recalled, the security guards, having learned that he was developing the app, immediately stood and gave him a salute.

On the day of the launch of Zhejiang’s health code, the electronic government office of the general office of the state council instructed Ali to accelerate the development of a national integrated health code system.

Two days later, CCTV news featured the Zhejiang health code.

All the provinces soon wanted their own version.

So, on Feb. 18, Ali Cloud’s data intelligence team stood up four teams to bring the code nationwide. Hubei’s algorithm rules were the most complex.

“That green code, that green color—for a long time, it was hope.” Li said.

The road from Hangzhou Yuchang Green Code’s Feb. 7 launch to YiChang Prefecture, Hubei’s first green code on March 6, was just one month.

The long march that China’s tech giants have been trying to accomplish for nearly two decades —one platform covering Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, or a remote frontier or mountainous region—took just one month.

For thousands of years, humans and information have been two separate things. The invention of language, writing, printing, the telegraph, and the Internet made it easier for people to find information. After entering the era of mobile Internet, the smart phone has turned into humanity’s information organ.

But getting this mass of information out efficiently and accurately amounts to a revolution, and cloud computing is what underpins it.

In March 1953, the world had only 53k bytes of high-speed memory (RAM). Today, smartphones have 100,000 times that amount. People and information are already one. The essence of health code is to reshape the relationship between people and information, and to promote the emergence of strong information people.

But the creators of health codes don’t feel like heroes.

“What are we compared to the health care workers who are on the front lines of the virus and life and death?” Li said, “I only hate that I can’t go to Wuhan to participate in the construction of the temporary hospital.”

China Twitter Tweets of the Week + A Contest!

Here at ChinaTalk, we’ll run this contest! You have one week to email me your best 500 words on this topic. Satire and straightforward analysis both accepted. The winner gets $100.