How The Chinese Internet Turns ‘Hong Kong Independence’ Into A Smear

Also: Paul Triolo on the Chinese Government's Relationship to Technology

I’m Jordan Schneider, Beijing-based host of the ChinaEconTalk Podcast. In this newsletter, I translate articles from Chinese media about tech, business, and political economy.

This week’s episode with Paul Triolo of the Eurasia Group on China tech policy and competition came out particularly well. We talked Huawei, export controls, Europe’s response, and industrial policy. Here’s an excerpt from the beginning of our conversation.

Clearly the Chinese government saw the technology not as threatening necessarily but as enabling, both from an economic, governance and control point of view. They could have decided on the internet, for example, to do a white list like the Saudis. But instead they chose to do a black list, and to not throttle the technology development. They’ve kept ahead of it.

The governance capacity piece of it people miss. They view technology early on as enabling them to do better governance, both the good, and the things that people worry about in the west like techno-authoritarianism and surveillance.

The Chinese leadership has alot of engineers and I think this idea of engineering society accounts for this desire to use technology in ways to deal with difficult problem of governing a giant country. They saw technology, maybe niavely in some sense, as a way to solve the big problems that China faces, from water issues to controling a population.

The government’s biggest blindspot is its own role. If you look at China and the success of tech firms in the private sector, it has really been driven by companies that are operating in very competitive markets like Haier, Huawei, DJI. These are companies that may have come out in part of the state sector and had some benefits in terms of subsidies, but for them to be global players, that’s not the government driving it. The government may be playing a supporting role, they’re a customer, but they’re really competing at the cutting edge. So doubling down on Made in China 2025 and other industrial policy makes it tough to create global players. Letting market forces work is a beautiful thing and that has produced arguably China’s most successful tech companies.

Fang Kecheng, a widely renowned commentator and former journalist at the Chinese newspaper Southern Weekly, is currently teaching at City University of Hong Kong (CUHK). Recently, after posting on the video platform Bilibili, he was subject to a vicious online harassment campaign, with many of his attackers accusing him of supporting Hong Kong independence.

Fang, however, has never supported Hong Kong independence. Yet even someone as moderate as him — who in this article advocated for nothing more controversial than goodwill and mutual understanding — can find himself on the receiving end of vitriol. Content moderation on Chinese media platforms rarely applies to nationalists: the many threats made on Fang’s life are still viewable on Bilibili.

On November 18, Fang published an article on his WeChat account about this ordeal, which has been viewed more than 100,000 times. This piece gives us a look at what a culture of online nationalism looks like, especially when warped within the Chinese media ecosystem. The highest-rated comment to Fang’s article reads: “It’s an illusion; the Red Guards have never left.”

Fang, a media veteran, framed the following article in such a way as to ensure his article would not be censored and perhaps garner the most support for a wide audience of mainland readers perhaps skeptical of his political leanings. It is still available to read here in Chinese, and we’ve translated it below.

This translation first appeared in SupChina, an independent digital media company dedicated to informing, entertaining, and educating a global audience about business, technology, politics, and culture in China. They also host my podcast!

This edition of the newsletter is brought to you by Outlier Linguistics.

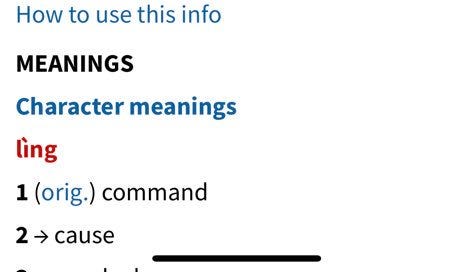

Every time I have to whip out my phone to look up something in Pleco, I get a little depressed, having just reminded myself of how little Chinese I really know. But the Outlier Linguistics Pleco add-on has turned Pleco from a chore to a delight. For most characters I look up, thanks to the Outlier add-on I get to learn an always useful and oftentimes hysterical etymology.

For instance, the other day I stumbled upon the Outlier entry for 令 (to command) and learned that its original meaning came directly from two form components of a mouth commanding a kneeling person. Having this is my head will make sure I never forget which components make up the character.

Click here to learn more and enter the code ChinaEconTalk for 25% off.

The five days I was attacked by the internet

By Fang Kecheng, translation by Pieter Velghe and Jordan Schneider

The night of “Singles Day” [November 11], I released a new video on Bilibili. Using the “interactive video” function introduced by Bilibili this year [sort of like a choose your own adventure but for video], I posted a test about “whether you are suitable to do a Ph.D.”

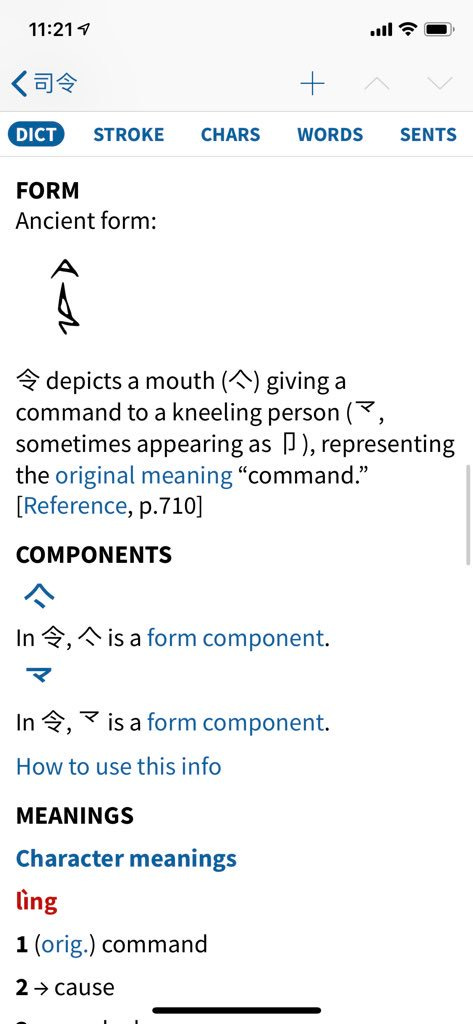

A day or two later, the comments section looked normal. But on Wednesday (November 13), this video was suddenly flooded with offensive comments. From the scale and speed that they came in, it was clear that these comments weren’t organic, and that it was part of a deliberate organized campaign.

These comments were hasty, full of distortions, often with ghastly language.

Selected translation: two-faced, CIA spy, “burn joss sticks” ie you’re going to die soon, race traitor, faggot…you get the idea

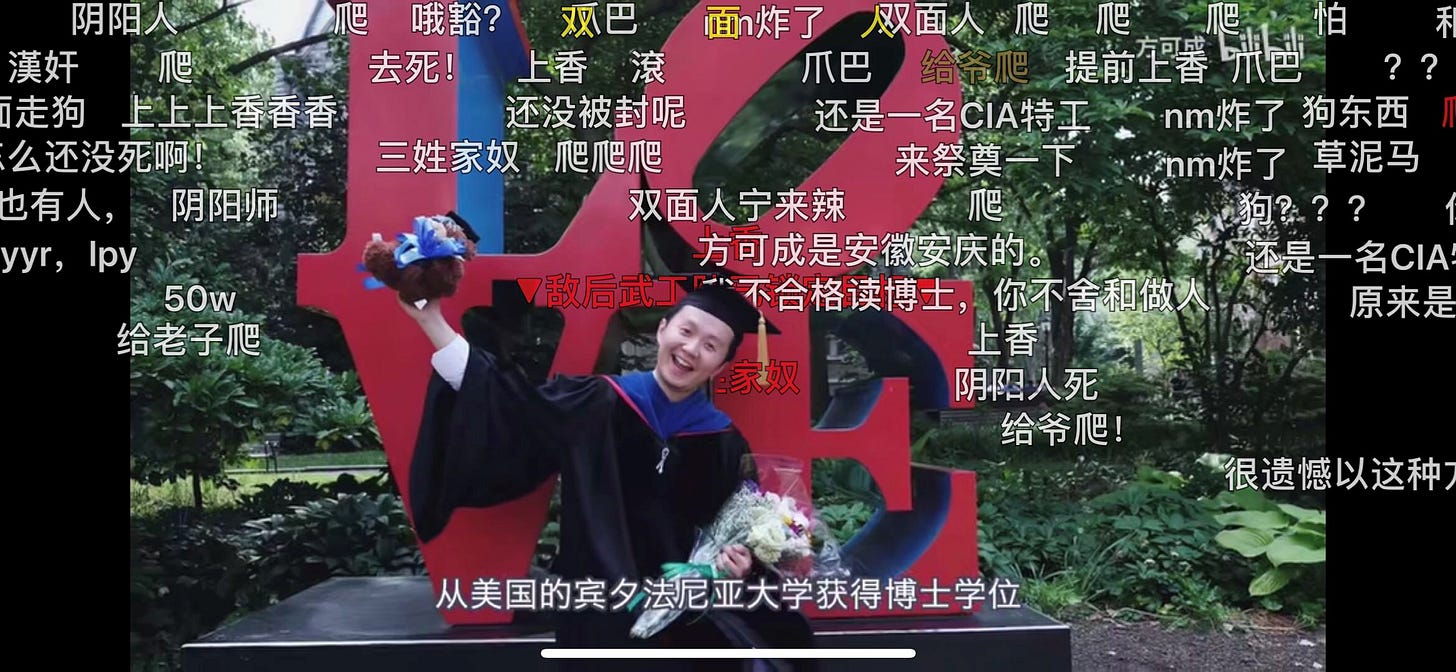

At the same time, hundreds of abusive messages poured into my private inbox on Bilibili. The following screenshots are only the tip of the iceberg.

“From the moment I saw you’re a reporter from Southern Weekly, I knew you were a foreign shit-eater. Please rip off your yellow skin and throw it on your daddy’s and mommy’s faces hahahahaha.”

As of today (November 18), these insulting messages have yet to cease.

The online violence wasn’t limited to Bilibili. It also extended to Weibo [Chinese Twitter] and Zhihu [Chinese Quora]. I had no choice but to change my Weibo setting so people could only post comments after following me for 100 days. [Interesting idea, cc: Dorsey].

The focus of this group’s attack was on the cooked-up charge of supporting “Hong Kong independence.” They collected far-fetched, so-called “evidence,” using absurd logic to force false labels on me, then using this as the basis to openly attack me. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

We should have long ago moved away from that era where people can be arbitrarily labeled and then be publicly humiliated and attacked. We should not allow online violence to stain our online space.

Hong Kong is ill. Violence is only a symptom. What needs to be cured is a deeper problem.

Here, I would like to state my basic position: I believe “one country, two systems” is an extremely great concept, and I support the fundamental state policy of “one country, two systems.” Hong Kong is an integral part of China. China cannot lose Hong Kong. I firmly oppose “Hong Kong independence.” I deeply love this land that’s under my feet. In fact, I have also said before that I feel very blessed to be able to work in Hong Kong after getting my Ph.D. One of the important reasons is that I can contribute what I have learned to this place. I hope to, in this international metropolis, work hard to build bridges of communication that seek common ground while resolving differences between East and West, and between the mainland and Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan.

I oppose the violent behavior that has appeared in Hong Kong society in recent months. I believe that those who use violence should be lawfully punished according to legal procedures. In recent days, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), where I work, has become a battleground, and the school was forced to end the semester ahead of schedule. I feel very sad about this. I miss my students and class very much. I hope the university can resume normal operations as soon as possible. I hope the whole of Hong Kong can restore its stability as soon as possible. I hope the Pearl of the Orient can overcome this crisis and regain its brilliance.

In my opinion, the elimination of violence and the restoration of stability depends not only on the power of law enforcement, but even more on carefully researching and understanding the crux of the violence and on the promotion of communication and dialogue. Hong Kong is ill. Violence is only a symptom. What needs to be cured is a deeper problem.

In fact, I only started working in Hong Kong in August, and my understanding of Hong Kong is still very limited. Therefore, in the past three months, I’ve basically not expressed any views on the issue, because I am aware that I do not have the qualifications and ability. All I can do is look more, listen more, observe more, and think more.

In other words, in the past three months or so, I haven’t made any comments on Hong Kong, let alone any statements in support of Hong Kong independence or violence.

So how have my online attackers on various platforms tried to `pin me down as having done so?

The so-called “evidence” they threw out approximately falls into these categories.

The first is an article I shared on Facebook. I don’t know what legal channels they used to access Facebook, but they took screenshots of my page.

They claimed that I “shared support for mob behavior,” then posted those screenshots, even though these were only the observations of my colleague at the front line of the conflict in CUHK. When this happened, I was not on campus. In fact, I was very concerned about what happened at my school. If this is evidence of guilt, then all those who have forwarded posts related to the situation in Hong Kong, are they pro-Hong Kong independence too?

Another screenshot they put out was of an episode I shared about Hong Kong by This American Life, a well-known American podcast. In fact, this program did not express any opinions, but interrogated all aspects related to the situation, and aimed for depth of understanding of both sides. I think this kind of program is valuable. It promotes understanding and communication on many aspects and presents different perspectives. It has nothing to do with “Hong Kong independence.”

And so on. There have been quite a few. Their “evidence” even included a poster of when I participated in a salon a few years back. The theme of the salon was, “How do citizens talk about politics.” Citizens talking about politics is a daily occurrence in a normal society. What is the connection with “Hong Kong independence”?

They also claimed that there was something wrong with my Facebook profile picture. On the day after “Reporters Day” [one of five professional appreciation days in China, along with Teachers Day, Nurses Day, Doctors Day, and Farmers Day], I began using a photo of me wearing a reporter’s reflective vest, writing in the photo caption, “I am no longer a journalist but am training more reporters to report the truth and serve the public.”

If wearing a press vest is a problem, I would like to invite all internet vandals to take a look at the following picture.

Everyone should know the person in the photo: Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of Global Times. I don’t know, would you internet vandals also label editor-in-chief Hu as supporting “Hong Kong independence”?

In a torn society, we especially need journalists who pursue truth and promote communication. I am very proud of and cherish my identity as a former journalist and teacher of journalism. I have also been committed to promoting media literacy through various channels and emphasizing the importance of the quality of information. I absolutely do not believe that this can become evidence of “Hong Kong independence.”

Third, they find my articles are also problematic. However, they actually didn’t finish reading my 20-plus-page English papers. They just looked at the titles and started interpreting each word without understanding the meaning. For example, when I wrote a paper on “Little Pink” [about China’s cyber-nationalists], they claimed that my paper was criticizing these “Little Pink.” In fact, my paper was actually clarifying the label, as I traced the origin of the word and wanted to point out that it was not a proper label. [Ed’s note: see our translation of one of Fang’s articles on this subject.]

Others mentioned my only Chinese paper in recent years (published in Fudan University’s News University magazine), saying that it was an “enemy intelligence investigative report” I made for the CIA. Another person responded by saying, “That makes sense.”

One of the online users from Bilibili couldn’t see further than that, and so started hating.

If the attackers are willing to carefully read my papers and other articles, I welcome them to, and can even provide them with free PDFs. However, if the attackers only read with the aim of looking for evidence of “Hong Kong independence” or “espionage,” they will be very disappointed, because there isn’t any.

The online violence that lasted for so many days, with use of so much obscenity, was based entirely on unconvincing “evidence” and logic. It is any wonder that some onlookers were worried? Can anyone give us some hard evidence?

The rhetoric that exaggerates differences, dangers, and hatred deepens misunderstanding and estrangement between the two sides.

In the past three months or so, I have made only two statements on Hong Kong. These weren’t big comments, but just personal observations of life here.

One was “a trivial record of the night of October 4, 2019, not of much value, but just a micro-perspective of these turbulent times,” which I posted to Weibo on October 5. In this post, I recorded how the students in my class were affected by the turbulence and did not have public transportation to go home after class in the evening, but in the end were all brought back home by friendly strangers.

Some people were very dissatisfied with the content of this message, saying that it falsely claimed that the situation is peaceful. But in fact, living in Hong Kong, I know that it is not all peace and quiet. Then, how to cool down the whole situation? I think a fundamental way is to revive goodwill. I truthfully recorded what happened on the night of October 4 and stand by every sentence. But I also want to convey a certain attitude.

Another message is one that I recently posted in my Wechat Moments. The gist is this: Hong Kong has not seen systematic hate crimes directed at mainlanders, so there is no need to panic, let alone instigate hostility. This is based on my genuine feelings of living in Hong Kong — I speak Mandarin every day and have not encountered any danger. I have seen many mainland students get along well with local students. Local students also respect me very much.

In fact, Hu Xijin pointed this out in a recent Weibo post: “So far, except for one beating of an HKUST student, no other mainland students in Hong Kong have been directly injured or illegally detained.” He also said that mainland students who are willing to stay in Hong Kong “pay more attention to the fact that there is no actual persecution of mainland students around them and believe that there’s not much chance of such an extreme situation happening.”

Hu Xijin’s post on Weibo

I hope that panic and hatred will not spread. Anyway, this is only a selfish thought: I hope to personally be safe in Hong Kong. But to be safe, the precondition is that the differences between mainland and Hong Kong people should not be artificially inflated. The rhetoric that exaggerates differences, dangers, and hatred — while on the surface looks like an expression of concern for mainlanders in Hong Kong — may in fact utilize distorted information and lead to a “self-fulfilling prophecy” and deepens misunderstanding and estrangement between the two sides. That’s like pushing mainland people in Hong Kong into a fire pit.

Hatred and exclusion have never been the way to solve problems. Hong Kong people and mainlanders are both Chinese. What I want to think about is how to make Hong Kongers and mainlanders better understand each other, instead of pushing away this piece of land that belongs to all of us, together.

Starting from September, I’m taking Cantonese lessons every Saturday. Although I can’t converse in Cantonese yet, I hope I can still communicate with and understand the people here more and gradually integrate into this place where I work and live. I hope I can have as full an information intake as possible, that I can continue to think rationally, and adhere to integrity and kindness.

Looking at the foul language in my private messages in Bilibili, I think, what is the fundamental difference between those who commit online violence and the organizers behind them, and those who in real life who pour petrol on the elderly to set them ablaze?

These are all acts of pure evil.

We cannot expect flowers of hope to bloom from evil.

What warms my heart is that in recent days, many friends who I know and do not know have sent messages of care and encouragement. They convinced me that the world still has kindness. Kindness between people is the fundamental reason why we still have hope for the future.

Only by continuing to observe, listen, communicate, understand, think rationally, and reject violence and hatred can we rebuild our common and beautiful home.

Finally, I would like to say: I am not writing this article to try to persuade those who attacked me online — since it was a deliberately organized act, it means that many of them may have refused to communicate and think a long time ago. They just follow orders and rush toward a fabricated label. They might even again quote this article out of context. I don’t care what they say. However, after so many days of continuous attacks, I think I should restore the truth and show my position, which is the most responsible thing I can do for everyone.

Thanks for reading! If you’re interested in translating (I can pay!) or joining the ChinaEconTalk wechat group, please add me at jordanschneider.