Does America still have what it takes to stand up to China? Does short-term military readiness trade off with long-term strategy? What does the US need to do today to stay competitive for the rest of the century?

‘

’ is the author of Breaking Beijing, a Substack examining the military dimensions of US-China competition. Tony’s Substack goes deep on subjects you didn’t know you needed to understand, like Arctic policy, and takes a refreshing step back to look at great power competition holistically. Tony wrote Ex Supra, a sci-fi thriller about a near-future US-China war.We discuss…

What it will take to win the 21st century, and what America needs to prioritize in the short, medium, and long term,

Why investing in education, basic science research, and foreign aid pay dividends in military readiness,

Why Washington is short on coherent China strategy,

Taiwan’s impact on global nonproliferation efforts,

How AI could change warfare, even if AGI can’t be considered a “wonder weapon.”

Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app.

A Blueprint for Competition

Jordan Schneider: Tony, why don’t you share as much autobiographical information as you feel comfortable?

Tony Stark: Tony Stark is the nom de plume that I’ve used for years. I’m a China policy guy by both research and practice, with some background in tech research. I served in the US Army infantry, formerly active duty. I worked on Capitol Hill and in OSD, and now I’m in the private sector trying to help the US win the 21st century.

Jordan Schneider: Let's talk about the endgame for U.S.-China relations — you called it Plan Noble. When people talk about the endgame for U.S.-China relations, what should they actually be talking about?

Tony Stark: What they should be talking about is how to make the world unsafe for the Chinese Communist Party while making the world safer for Americans and Western-style democratic order. That is the ultimate endgame. Anything else where you talk about trying to depose the regime, or regional areas of control between democratic and authoritarian powers, doesn't actually solve anything, and it doesn't put you in an advantageous position. You're either ceding too much ground, or it's overreach. The goal is to make the Chinese Communist Party feel unsafe to follow their policy goals out in the world beyond their shores.

Jordan Schneider: Can you talk me through your decade-by-decade framework for the competition?

Tony Stark: 2025 to 2030 is your rough near term. That's your immediate threat. That's where the investments that you've already made or perhaps chosen not to make are directly impacting your ability to operate from a military standpoint in peacetime or wartime.

What you're trying to do now is focus on investments that you can produce and get off the production line in the next one, two, three years. You're focusing on maximizing that production, showing steady state investment to industry, both in terms of workforce and production. You're starting to invest in things that are attritable, because if you're only investing in exquisite systems, you are not really able to plan for a longer fight in the event that you get into one.

There are things that you have to do to ensure that we're still competing in the 2030s. This means prioritization to ensure deterrence in and around Taiwan. It means starting to build relationships throughout Southeast Asia, so if there are other contingencies you have to worry about, you could start laying the groundwork there.

Additionally, what are the basic R&D investments that you have to start to do from an AI side, quantum, synthetic biology? It starts today. The discussion in China policy over the last five to ten years has been, “We should have done this ten years ago. We disinvested of all these things in the 1980s and 1990s, and this is where it got us.” Now you can think about that from a forward-looking perspective — what do we need to keep and buy today such that in 2040 we’ll be saying, “Thank God we invested in that”? Now is really your last opportunity. You have to do it now.

Beyond 2030, that's when you start to see payoffs from large-scale industrial investment, education investment. Investments you start today start to pay off. 2030 to 2040, the big one is AUKUS. You're looking at smarter machines. You're looking at new weapons systems that are coming online that might be in initial rate production today, and you're looking at all of the new doctrine coming out across the forces that is actually getting their reps and sets internally for training and now being able to be demonstrated.

People usually use the 1980s example of the Abrams, various fighter jets, etc., that, between that and the combination of new doctrine through the ‘80s of air-land battle that culminated in the Gulf War, that's what we're trying to pursue for the 2030s. You’re getting to that point where not only have you managed to stave off destruction today, but you are also prepared for a higher-end fight with an even more capable People’s Liberation Army in the 2030s.

In the 2040s, your early R&D bets start to see payoffs. Consider this as buying in on a company that has maybe five employees and then might expand out to a real-sized corporation by then. You’re doing the government investment equivalent of that for any sort of R&D project or force design. Quantum and many of the positive sides of synthetic biology are likely in that late 2030s, 2040 category.

Through 2040, you have to give yourself the maximum wiggle room to account for external events, changes in budget, etc., while still having this guiding principle of what we are doing is to keep the CCP contained, to make the world unsafe for their operations abroad. That gets us to mid-century.

Jordan Schneider: In order to make sure we don’t find ourselves in a World War III or happen to lose it over the next 30 years, what is the first thing that folks should be thinking about, focusing on, and shoring up?

Tony Stark: You have to be able to build, acquire, and deploy things today that work. Where some of the scholars and leading thinkers — Rush Doshi, Elbridge Colby, and others — get torn up in debating this is whether to prioritize short-term or long-term, and you can’t just choose one. You have to do both. That’s the very difficult reality.

You need to hold that five-meter target — “What if Xi really wants to move in 2027, 2028, or 2029? What do we have to do today? What can we feasibly do today to prevent that? How do I do that in a way that still allows me to invest in the long term?"

Yes, you have this sprint in front of you, but if you burn all of your energy in the first mile of a 26-mile race, you will lose. Simultaneously, if you just go at an easy pace, at your own pace, irrelevant to the competition in your marathon, where is your competitive spirit? You’re definitely not going to be the first at the finish line.

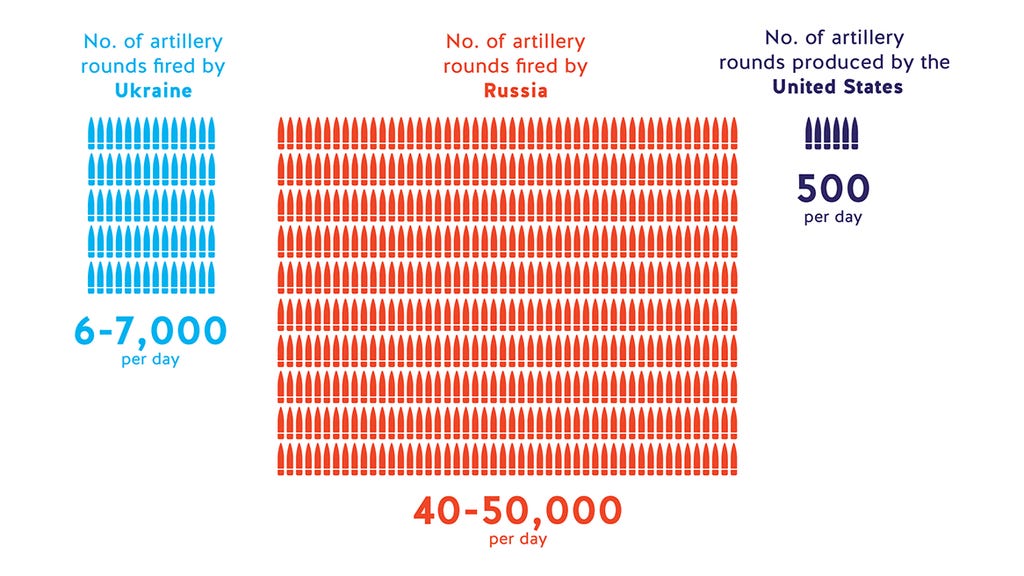

What does that specifically look like? Unmanned systems and munitions. Munitions are probably the biggest investment you can make, because magazine depth is just an exorbitant challenge. At the high point of Ukraine operations, they were burning 60,000 rounds of artillery a day. The Pacific fight involves a different set of munitions.

Really, it’s about ramping up production and giving the industry that signal of, “You are reliably going to get investment from us for the next few years. This is our priority.” A lot of our tech works. There’s not a whole lot of areas where we’re saying, “If we had a new main battle tank by 2027, we’d win the fight.” The Abrams is pretty good. But I would like about 1,000 more long-range anti-ship missiles. Everyone would. That’s obviously capped by actual production rates, but I think you get the idea.

Jordan Schneider: Maybe going one step up from that — you’ve got to want to do the competition. You wrote a piece back in 2023 entitled “Where Did All the China Hawks Go?” We’re recording this March 21st, 2025, and it is still very unclear just what this president’s stance towards China and Chinese territorial aggression is going to be.

You can lose before it even starts. We’ll get into the acquisitions stuff and force structure stuff in a second, but you can lose at a systems level in two ways. First, you don’t even show up, and second, you stop being the system that you initially thought you were in the first place.

This is a global beauty contest as much as it is a competition between the US and China. If America is a less attractive partner for ideological reasons or for reliability reasons, then that’s a problem. The US and China together add up to less than 50% of the world’s GDP. There are a whole lot of other countries that are potentially up for grabs, that are going to choose which way to lean over the coming decades.

As nice as magazines are, it’s nicer to have the entire industrialized world on your side versus on the other side. I go a level up personally when thinking about this problem.

Tony Stark: 2015 is a good place to start looking at China Policy because that’s when the South China Sea island development and various hacking operations hit their peak, in the Obama administration.

That was the start of when, aside from us wonks, people needed to start paying attention. The Trump administration focused on deterrence by denial. There was a mix there where President Trump was friendly with Xi Jinping, but there were also tariffs, and those in the DOD under Jim Mattis and others were trying to figure out how to fight in the first and second island chain — how to show up to the fight.

The Biden administration took a different approach. They had to continue some of the Trump administration’s legacy of being able to fight in the first and second island chain, but they also said, “We’re going to do industrial policy. Not only are we going to show up to the fight, but we’re going to show that America is strong enough to survive that long fight, that competition.” That’s the CHIPS and Science Act and parts of the infrastructure bill — what does that 15-20 year investment look like for us?

But simultaneously, they didn’t really like the idea of having to do this from a foreign policy perspective. It was not particularly convenient, and that was a challenge.

Here we are today in a world where we still don’t have a solidified China strategy. On top of that, there are not many champions of actual hawkish China policy in DC or around the country. You brought up “Where Did All the China Hawks Go?” It’s not particularly a blue or red problem at this point.

There are motivators on both sides where there’s less interest in China as a competitive space, whether that’s because of wanting to focus on domestic policy, the Western hemisphere, commerce, or making trouble with other folks, rather than saying, “This is the priority."

That’s where we are. We are adrift, and this is a really bad time to be adrift. I mentioned before that we should have done this 10 years ago. It wasn’t good to be adrift 10 years ago, and now we’re about to be adrift on a raft going into a hurricane. This is going to get really bad if we don’t figure this out.

Jordan Schneider: The urgency is less from an “I think Xi is going to invade in 2027” perspective, but from a comprehensive national power perspective. The Chinese military in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s was not a serious challenger on paper to the US and its allies. That is different now because China is richer, they have modernized, and they are able to project force in new and interesting ways at scale. You would have to go back to the early Qing dynasty to have a relative power comparison to what we’re looking at today.

It’s not a bad thing that a billion people in China are richer than they used to be. However, we’ve all learned this very horrific lesson of what autocrats can do with Putin in Ukraine. Even if you think Xi doesn’t necessarily have bad intentions over Taiwan, building a deterrence capability ensures that whoever’s leading China over the next 30 years understands it would be devastating for them to start a high-intensity conflict. This seems like a reasonable insurance policy for the US to invest in.

Tony Stark: Over the late Cold War and definitely over the last 30 years, we’ve become accustomed to being able to pick and choose the fights we enter or how we engage in them. With 9/11, we didn’t pick that fight, but afterward we maintained this idea that we can go anywhere, be anywhere, and simultaneously withdraw if we want.

Some leaders in Washington might decide, “We don’t really want to pick a fight with the Chinese.” That’s understandable. We didn’t really want to pick a fight with the Nazis either in 1937, and we still ended up having to confront them. Wars happen because of fear, honor, or interest. The enemy gets a vote, and if they decide that fear, honor, or interest requires them to either fight us, challenge us, or push us around, then they will do so.

Elbridge Colby said, “Taiwan is not an existential problem for us.” Not in the sense that losing Taiwan means the end of humanity. But it’s like hanging off the edge of a cliff and having one hand slip. We’re already at that precipice. If you lose Taiwan, yes, you lose face, and you lose TSMC. But there are also 24 million Taiwanese who would fall under the boot of a regime that believes they should not exist.

This situation triggers concerns for every ally or potential ally in Asia and Europe that the US might not be there to back them up. “The authoritarians are on the march, and this might happen to me.” That either leads these countries to surrender or to acquire nuclear arms. Nuclear proliferation is something you don’t want to pursue. That’s where the existential problem for America transitions to an existential problem for humanity — when you start worrying about nuclear proliferation. The more fingers with access to nuclear buttons, the higher the risk of nuclear conflict, which nobody wants.

Jordan Schneider: The question is whether we’ve already crossed that threshold with what we’ve seen coming out of Trump’s diplomacy over the past few months.

We’re going to do a whole show on global nuclearization in response to America’s treatment of NATO. It’s really dark.

Tony, you have a recent piece about the evolution of combined arms warfare. What is your mental model when trying to evaluate what changes could be coming to the battlefield, and how to invest around them?

Tony Stark: Everyone focuses on what we see in Ukraine, and I think much of that is applicable. When discussing a potential US-China conflict, you also have to understand that Chinese capabilities are technologically superior to the Russians in many ways. You probably have to increase that threat assessment significantly. This isn’t to make the Chinese sound invincible, but to understand the substantial difference between Russian and Chinese technology in certain areas. The Chinese are undoubtedly learning many lessons from the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Regarding the future battlefield, we’re evolving from traditional combined arms warfare that has existed for the last 150 years. Combined arms warfare integrated radio, control, precision fires, and different military branches at both joint force and service levels to synchronize effects and damage the enemy. This involves coordinating artillery while infantry and tanks maneuver, with tanks and infantry working together rather than in separate formations. That’s the basic concept for the audience.

Now, we’re taking all that learning from the last 150 years and applying it to unmanned systems that, at a rudimentary level, can think and perform tasks autonomously at a narrow level. The challenge is determining what’s best for humans to do, what’s best for machines to do, and where they work in concert.

For example, the Ukrainians still need soldiers and manned tanks on the front lines, but there are particularly dangerous areas where they operate, such as the combined arms breach — blowing a hole through enemy defenses. The enemy knows you’re coming, likely knows where you want to breach, and has artillery, wire, mines, and other defenses in place to prevent this. You don’t want to be the human in that situation, even if you’re in a tank. I could send you countless videos from Ukraine demonstrating why. But if you can send machines to do it, you reduce your exposure while accomplishing the rest of your mission.

That’s the first part of robotics and unmanned systems as enablers for shooting, moving, and communicating. They allow you to shoot with better precision, communicate more effectively, and move either faster or in more dispersed ways. These are the fundamentals of warfare.

Moving to the shooting aspect, Ukraine uses what they call one-way attack UAVs or even USVs in the Black Sea. These rudimentary war robots make decisions independently or are remotely controlled, functioning to collect information, transmit it to personnel behind lines, and target and strike. This represents the next iteration of artillery, close air support, and long-range fires.

The final component is maneuver — infantry, tanks, and other forces pushing through, fighting through the enemy, taking and holding ground. This is the hardest component because it requires relying on those previous capabilities — collecting information, shooting, etc. — and combining everything into one package that must be survivable. While machines are more expendable than humans, they’re still expensive and time-consuming to build.

The challenge is creating something that can survive in harsh environments. Cold, heat, rust, and moisture annoy us as humans but don’t typically kill us, unless you’re in extreme conditions like the Arctic. However, machines have specific thresholds, often lower than humans, for what they can operate in. How do you ruggedize equipment while ensuring it keeps pace with the rest of the formation? How does a ruggedized unmanned vehicle with a 50-caliber weapon maintain pace with tanks moving at 30-40-50 miles per hour, while remaining survivable, maintaining targeting capabilities, and withstanding being thrown and bounced around with all its internal electronics?

Essentially, you’re asking for the equivalent of a ruggedized iPhone or laptop to survive being bounced around on high seas, in mud, in swamps, etc. That’s extremely challenging, especially to get it to do all the things you want it to do. There’s a lot progress in the startup world and even among major defense contractors, but this represents the current battle laboratory we’re witnessing.

Jordan Schneider: This is a good counterpoint to the narrative that AGI is going to change everything once and for all.

In Watchmen, which is a great graphic novel that was turned into an excellent HBO series everyone should watch, Dr. Manhattan is a superhero that America deployed in 1974. He shows up in Vietnam, and the war ends five minutes later because he’s essentially a Superman-type figure. America’s ability to control him simply wins wars without discussion.

It seems implausible that in the near or medium-term, AGI is going to create a gap in capabilities at the level of the US versus Iraq in 2003.

Tony Stark: To that point, as a reminder to everyone, please do not connect the nukes to the AI. Please do not do that.

Regarding the Dr. Manhattan concept — your AI is only as good as your data. We don’t actually know what the equation is to get us to AGI. You’re not looking for the Higgs boson where you think, “I believe it’s in this range and if we get there, I just need to look in the right space.” It’s as much a philosophical question as a scientific one.

I would discourage those who claim that AGI will solve battlefield problems from strategic decision-making to having some “wonder weapon.” That’s not happening.

In the next 10 years, you’ll see incremental gains from AI in tactical decision-making, data processing, the ability to find, fix, and finish targets, as well as logistics.

Logistics are probably the most significant use case for AI because humans are really bad at efficient logistics.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk more about the “wonder weapon” concept. Historically, these were terrible ideas. Hitler kept thinking he would invent one weapon that would win the war, and it didn’t work. He didn’t even know he should have been focusing his resources on nuclear weapons instead of three-story tall tanks and V2 bombs.

The enemy has a vote. The enemy can copy and counter what you do once you deploy it. War is much messier, and there is no single trump card that can help the US beat China.

Tony Stark: Exactly. Some of that perspective comes from how we teach history, either at the popular level or undergraduate level — “The allies got the bomb, and then we beat the Japanese.” In reality, many other things happened before that to get us in that position.

I really like your point that Hitler didn’t even know the actual wonder weapon he should have been building. That’s a perfect comparison to AGI. I assure you, if you try to chase AGI by itself, you will not reach your goal.

If you focus on very narrow applications — and I say narrow in the AI context, not meaning you just do one thing — if you focus on applied tasks that will actually have effects at the tactical and operational level, as you start to aggregate those systems, you’re learning valuable lessons. You’re proving what does and doesn’t work, and that’s not just about the machine, but about how to develop AI itself.

Jordan Schneider: Foreign aid is a rather spicy topic lately. We’ve seen USAID seemingly hitting a giant destructive reset button. Tony, what’s your pitch for spending money in a broadly aid-focused sense in foreign countries?

Tony Stark: I wrote an article a while back called “Fighting the Four Horsemen.” The Department of Defense fights war, which is one horseman. Foreign aid fights the other three — pestilence, death, and hunger — which cause pain and are often drivers of war.

Do our foreign aid programs get everything right? No. I can’t think of a government or corporate investment plan in history that got everything right. Everyone has a pet project they want to work on, or they simply make bad guesses. Your data won’t be perfect, and you have to plan for that.

What does foreign aid buy us? It buys goodwill, which sometimes matters when you’re a soldier stuck behind enemy lines and somebody remembers, “The US government fed me during a famine.”

It also allows us to prioritize the things that matter. If we prevent a famine in Africa, then we don’t have to deal with the economic and possible military fallout of that famine. From a purely realist standpoint, this prevents us from having to dedicate additional resources when we need to focus on the main adversary.

At its most basic level, that’s what foreign aid does for us. Obviously, it does many other things — it fights viruses at their source, prevents outbreaks, and if outbreaks occur, prevents diseases from spreading through early identification. All these things matter when discussing how we create stable institutions at home and a stable, prosperous economy for more Americans. As we’ve seen, viruses and ecological disasters hinder those efforts. You’re fighting many threats abroad through foreign aid so they don’t come home.

Jordan Schneider: I couldn’t have said it better myself. The Office of Net Assessment is being canceled. Hopefully it’s just a reset button and won’t disappear forever. But I think there are parts of this new energy in Washington which aren’t even anti-intellectual — they’re anti-thought. You should do things because they seem “based,” as opposed to actually putting in the time to think about costs and benefits.

Tony Stark: US history throughout the Cold War is littered with examples of times when we simply didn’t understand the ground state of things, and we either made situations worse or ignored them. I can think of any number of coups or civil wars we got involved with in the ’50s and ’60s that might have gone differently if we had actual people on the ground. That’s an example of where information matters. You cannot simply look at the globe and decide, “I want to do that.”

The broader case for education is that an informed population is more independent. America is a nation based upon choice, opportunity, and independence. An educated civilian populace leads to prosperity — that’s simply the equation.

I’m not saying that everyone needs a college degree or a master’s degree. I don’t agree with that, and that’s not how the economy works. You need people in trades. You need people who join the military at 18 and go to college later in life.

When I talk about education, everyone focuses on higher education because that’s usually their most recent memory, that’s the fun part, and that’s where you get into politics because you’re 18 or older. K through 12 education is largely neglected.

Jordan Schneider: Can you illustrate with the anecdote about Army recruits with literacy issues?

Tony Stark: As a former Army infantryman — I enlisted after college because I decided I needed to earn my way to leadership — within the first two weeks on the ground at Fort Benning, you go through what is basically a leadership training course. What it really involves is going from station to station with your group of recruits.

You read about a particular Medal of Honor winner and try to complete team-building challenges. You can probably imagine what that’s like — an outdoor course where you need to get across the fake lava by putting planks together or something similar. When you inevitably fail, you do a lot of push-ups or burpees.

The drill sergeants make the recruits read the Medal of Honor citation. What struck me was how many recruits struggled to read their own history. That’s your lineage as an infantryman — the people who came before you and did great things — and you can’t read it. If you can’t read it, how can you understand your place in the world? How can you analyze things on the battlefield? How can you make decisions in complex modern warfare?

People might argue that in the 1800s, half the recruits couldn’t read. It’s a different story now when you have to operate drones and tanks. You need to be literate and able to make complex decisions.

A Marine Corps report came out a couple years ago stating that the ideal infantryman is around 26 years old with a bachelor’s or master’s degree. The population can’t support that, and frankly, I don’t think you actually need that. What you’re looking for is a more well-educated population through K through 12.

Jordan Schneider: When you see people with degrees from prestigious institutions expressing thoughts and logic that demonstrate brain rot from short-form media and Twitter — it’s evident that their content consumption has shifted dramatically over the past five years. That’s a scary transformation to have witnessed closely over recent years.

Tony Stark: Don’t get me wrong — I enjoy funny Instagram reels too. The point is that reading from an early age teaches critical thinking because you have to read, decipher, and learn about the world.

Never let anyone convince you that humans aren’t built upon curiosity and research — we are. If we give people the right tools, they will research sciences and social sciences rather than QAnon conspiracy theories.

Jordan Schneider: What are your dream pieces of legislation?

Tony Stark: I would like to see multiyear procurement for weapon systems. I know there are Congressional limitations on spending beyond two years, but multiyear procurement, especially for long-lead items, would be beneficial.

I would also like to see legislation on refining our economic warfare capabilities. I wrote a piece a long time ago about a Department of Economic Warfare. That doesn’t necessarily need to be created, but it’s clear that each economic warfare component — whether it’s the Bureau of Industry and Security or the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in Treasury — advocates for policies from their own perspective. That’s the nature of Washington.

This makes it difficult when facing a massive economic competitor like the PRC. You have people in some departments saying, “Our priority is investment,” while others say, “Our priority is hunting down terrorists.” This leaves us asking, “What tools do we reliably have to fight the great economic competitor that is the PRC?” I’d like to see legislation addressing that.

Jordan Schneider: Any book recommendations?

Tony Stark: I think Rush Doshi’s The Long Game is valuable. I don’t agree with everything Dr. Doshi presents regarding his assessment of the broader threat matrix of the PRC. However, if you want to read the party in its own words — because I’ve encountered many people in the DC policy community who ask, “What are the Chinese saying?” — there’s a book right here that documents it.

You can read it if you choose to. Literacy, again, is important. That’s one recommendation.

Number two is Spies and Lies by Alex Joske, because everyone should better understand how our main adversary chooses to interact with people from an influence perspective. I found it to be a fascinating book. I’ve heard there were other case studies that were going to be included but weren’t for various reasons. So if someone reads that and thinks, “This is only 10 cases,” I assure you there are more.

You have to read Chris Miller’s Chip War because the semiconductor problem, like most supply chain problems, is incredibly dense. He presents it in a way that’s very accessible and goes beyond simplistic views like “TSMC makes chips in Taiwan and America wants control of that.” You need to understand why this is so important and the potential economic fallout if we lose TSMC in any fashion.

Jordan Schneider: I’ve read all three of those books. Regarding Chris’s book, it’s been out for two or three years, and it’s frustrating that no one has written a “Chip War for Robotics” or “Chip War for Biotech.” This book sold many copies. We need the industrial and global national security history of more industries.

Tony Stark: I would pay so much money for a “Chip War for Synthetic Biology.” For the Ex Supra sequel, I’ve consumed a vast amount of books on synthetic biology. Textbooks aside, most of them are very preachy. I was listening to one audiobook that said, “The Chinese might do some bad things in Xinjiang, but who can tell?” Clearly, they’re trying not to get their research canceled in Beijing.

I would really like to see that because it’s such a fascinating debate you can have with anyone in any policy community about how synthetic biology might impact you. Unlike Chip War, which is a very technical view of the technology, synthetic biology is darker. One book posed the question, “What if one day it’s immoral to not modify the genes of your baby?”

Building a Career in Writing

Jordan Schneider: All right. Tony, do you mind telling everyone your age?

Tony Stark: Yes, sure. I'm 29 going on 30.

Jordan Schneider: Awesome. When did we start Breaking Beijing?

Tony Stark: Two and a half years ago. Before that I've been writing on and off since I was in college.

Jordan Schneider: When I talk to students and student groups, oftentimes people ask me, "Jordan, what's your advice for getting into policy?" I say, "Start a Substack. If you're scared about using your own name, you can do it anonymously, and it'll still lead you into cool places, doing interesting things.” Here, we have the one and only Tony Stark, the perfect example of this. What advice do you have for folks debating whether or not to put their writing out in public?

Tony Stark: Write your own stuff. First, don’t use AI, but more importantly, write what you know and what you’re interested in. Don’t chase buzzwords.

If you’re thinking about stuff in your own way, that’s where your writing is going to come out best. It’s going to show as your own brand from a personal marketing standpoint, and you're also going to have a better sense of control over what you should and shouldn’t write.

Jordan Schneider: The most fun you will have in doing a policy writing job is when you get to choose what to write about. The best version of this job is you picking the topics that you're most interested in, reading about them, and then writing in your own voice and style.

This is the cool and scary thing about this field — it’s not like immersion lithography, which you cannot do unless you are at TSMC or Intel. You can write about policy just by sitting at your computer reading and writing. You shouldn't gatekeep yourself.

The other thing you said, Tony, which is really important, is that you want this to be the most fun part of your week and a repeated game that you play. You’re probably doing this on nights or weekends. It has to be exciting to you for a reason other than 4D career chess.

Tony Stark: Absolutely. I even tried, once or twice, to force myself to write on current events, and you just don’t get good quality work, especially if you're trying to use it as a way to promote yourself.

Secondly, reps and sets matter. I got really good at writing because I wrote frequently for work and in my personal life. Not all of it saw the light of day, but just writing and getting that feel for that, getting that feedback, going through editing — that’s what's going to make you better. It’s just like physical fitness.

Jordan Schneider: Can you talk a little bit about the doors writing opens, even if you only have, say, 2,000 readers?

Tony Stark: Before I wrote on Substack, I wrote on Medium, and I wrote threads on Twitter. I don’t think people understand how much policymakers, and especially staffers, are online and reading that stuff. They’re looking for feeds of information. They’re looking to understand what’s next, what’s current. That’s the space that you have to plan.

It will be a slow burn at first. I’ve had high-ranking commanders reach out to me. I’ve had high-level politicians reach out to me. I've been hired now at two jobs at least partially because of my writing.

It doesn’t happen to everyone, and it's not going to happen immediately, and you should pace yourself for that. Work on focusing your craft. But yes, it can happen.

Jordan Schneider: As a hiring manager, what you want to see is a body of work and sustained commitment and excitement to the topic, not just writing about critical minerals because it's in the news this week. The best way to prove you’re interested in something is to show that you've been thinking about it critically. It matters less if you are right or wrong, but just that you are being rigorous and analytical in your thinking on a topic is the thing that gets people excited.

Tony Stark: Another very important part is that you have to know when you are wrong. Maybe your writing cadence was wrong, how you phrased something was wrong, or a concept was wrong. People who stick to their policy viewpoints despite being proven wrong repeatedly, even if it's something very niche — the audience doesn’t like that. They want to see that you can iterate.

Jordan Schneider: By the way, when you're in your 20s, you're not like John Kerry running for president in 2004. No one is going to care whether or not you flip-flop on something. The idea is just to show that you are thinking and continuing to think about whatever it is you're interested in.

In your writing, you are manifesting the sort of doors that are going to be open to you in the future, and it's just better to do that about the stuff you’re passionate about than the stuff that’s current.

Tony Stark: Absolutely. You don't want to box yourself in, because all of a sudden, you become that one guy or girl that has the expertise, and you didn’t want to have that expertise. Now you’re stuck somewhere you don't want to be. It’s better to just follow your passions.

Jordan Schneider: Any other words of wisdom?

Tony Stark: Write what you know, don't chase other peoples’ ideas, and don't be afraid. You are already ahead of your peers because you are making the attempt to write.

Jordan Schneider: Here’s an open invitation — if you write five Substack articles, Jordan and the China Talk team will give you feedback. That is the new policy. DM me to have me review your writing.

Let’s close with discussing your book, Tony. I don’t read a lot of this genre...

Tony Stark: I don’t either. That’s my actual confession. People ask me, “What are your top 10 sci-fi books?” I get to five and then I’m stuck. I love science fiction, but I think I can predict where most books in the genre end because they’re so repetitive.

Jordan Schneider: The strongest elements for me were the out-of-the-box but still grounded military scenarios — warfighters in outrageous geopolitical or technological situations where there’s a cyborg assassin on your tail or drone swarms. Not drone swarms in a hand-wavy way, but as described by someone who was an infantry officer who has done the reading and can paint a grounded yet novel and provocative vision of what the future of war might look like. I’m curious, in your first book and now going into your second, how did you think about what visions of future warfare you wanted to portray?

Tony Stark: When I was in college, before I joined the infantry, I attended a defense tech conference where they were showing off various early-stage technologies. There were all these talks about the future of war, high-end conflict, gadgets, and push-button warfare. The following year, I found myself, almost to the day, trying to dig a ranger grave — a very shallow defensive position — in the backwoods of Fort Benning with a broken shovel. That experience embodies my perspective on future warfare.

I wrote something similar in the combined arms piece I recently published:

In 2025, a hypersonic missile can fly thousands of miles to strike a single target built on the backs of days’ worth of intelligence collection, analysis, deception, and SOF-enabled targeting behind enemy lines…and simultaneously, a few blocks away one guy can beat another guy to death with a shovel in the same war for the same piece of ground.

If you want to understand the combat operations in Ex Supra before reading it, that’s very much it. You have this high-tech fight, but the bloody, muddy reality is that you’re still going hand-to-hand. People are still dying in the mud. No amount of shiny technology is going to change that.

Jordan Schneider: Mike Horowitz sent me his History of Military Innovation thesis, and S.L.A. Marshall’s Men Against Fire was on it. I hadn’t read it beforehand. It’s such a strange book because the author is known for fabricating stories and exaggerating his battlefield experience. Yet, this book does an excellent job of capturing that John Keegan The Face of Battle approach in the World War II context, which feels very relevant to Ukraine and to other theaters today.

The reality is that despite the many drones in Ukraine, people are still sitting in trenches on the front line. Wrapping your head around the fact that this aspect is unlikely to disappear from warfare anytime soon — regardless of how advanced the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program is or how sophisticated robot technologies become — is important. There is a human element to warfare that has been with us forever and will likely remain for centuries to come, for better or worse.

Tony Stark: Another aspect of considering future warfare is not only what technology you think will work, but what technology you think will fail. I make this point about rail guns repeatedly in my story — that they somewhat work and somewhat don’t. Even the best high-end technology has shortfalls.

Jordan Schneider: One of my favorite World War II stories concerns American submarines whose torpedoes were simply broken. The trigger mechanism didn’t work until around 1944. All the submarine captains knew it and would report back saying, “Our trigger isn’t working. You need to fix this.” For whatever bureaucratic or acquisition-related reason, they kept being told, “No, you just need to be closer. You shot at the wrong angle. It’s your fault.”

This illustrates the future of war — having submarines capable of destroying aircraft carriers or battleships, but taking America three years to get its act together to truly leverage this technological advantage. Things don’t work as expected, learning happens at lots of levels, and AGI won’t solve these problems. We still need people writing unconventional analyses like yours, Tony, to help us conceptualize and think through the future.

Subscribe to Breaking Beijing and check out Tony’s book, Ex Supra, which is available now on Amazon and in independent bookstores near you!

Oh dear. I don't think you are thinking in the correct way; a bit Beltway? You can't outcompete China technically, they produce more graduate engineers annually than you have got. And you can't easily recreate the industries you have lost, or the skills of the workforce at all levels. Fit in with that in the best way possible. That's what we in Britain did when we passed the torch to you all - with many errors of course. Good luck!

So many gems in this one, thanks.

While it might seem to be a matter of semantics (it's not), I prefer to use "advanced AI" rather than AGI. Mostly for the reasons you raise. It's fine for the AI research community. It doesn't mean much for the DoD. It tends to lead people down the deus ex machina wonder weapon path, which is fraught, to say the least.

Unfortunately, despite all the excellent military and industrial policy advice proffered, you both hit on the critical policy shortcoming we're facing today: "it is still very unclear just what this president’s stance towards China and Chinese territorial aggression is going to be."