How to Grok the CCP: The State of Open Source China Research

What one think tanker learned from reading and blogging about the People's Daily every day for two years

Welcome to all the new readers from Michael Pettis!

In the first episode in a series on open source research and the CCP, I speak with the head of China research at Takshashila Institution in Bangalore, Manoj Kewalramani (@theChinadude). Manoj is the author of a daily briefing, Tracking People’s Daily, on Substack and his recent book is Smokeless War: China's Quest for Geopolitical Dominance. Transcription and editing by Callan Quinn.

Jordan Schneider: Before we get into why you started this project of writing 2,000+ words each day about what's happening on the front page of the People's Daily, Manoj, what is People’s Daily?

Manoj Kewalramani: The People's Daily is the Central Committee's mouthpiece. It's the highest organ of public propaganda that exists in China, and it's sort of the definitive media entity that exists in China.

And why it's important is basically because it gives you a glimpse into the thinking that's going on at the highest levels of the party elite.

It enjoys a certain hegemony over the entire media ecosystem in China so it sets the tone for what you're seeing in the rest of the media ecosystem.

That's not to say that there aren't other actors who sort of float around with other things or that there aren't market dynamics at play with other actors, but this is your definitive source to understand what the central leadership is thinking - as much as they would like you to.

Jordan Schneider: What is this Tracking People’s Daily project and what motivated you to start it?

Manoj Kewalramani: I started this last year when I was working on my book. I wanted to look at the discourse coming out of China with regard to the pandemic.

I used to do a small blog at that point in time basically looking at pandemic-related content in the People's Daily. As time went on, it became a habit. By March or April 2020, I was sort of religiously waking up and starting the mornings looking at the People’s Daily and starting to navigate through the pages and figure what's going on.

If I didn't go through the People's Daily one day, my day felt like it was meaningless, it felt empty. It was addictive in a way.

I enjoy putting ChinaTalk together. I hope you find it interesting and am delighted that it goes out free to eight thousand readers.

But, assembling all this material takes a lot of work, and I pay my contributors and editor. Right now, less than 1% of its readers support ChinaTalk financially.

If you appreciate the content, please consider signing up for a paying subscription. You will be supporting the mission of bringing forward analysis driven by Chinese-language sources and elevating the next generation of analysts, all the while earning some priceless karma and access to an ad-free feed!

Mining The People’s Daily

Jordan Schneider: You know Manoj, some people wake up and meditate, some people take a walk, some people pray, and I think all those things start your day off on different tones. What has doing this done to your brain?

Manoj Kewalramani: That's a good question. I think one thing that's happened is that it’s altered my appreciation of organizational dynamics, whether it is within my organization or whether it’s other institutions. I now tend to see most organizations as top-down [which isn’t always the case.]

Secondly, if you look at media in the West or if you look at media in India, it's chaotic. It's sort of scattered and all over the place. There’s somebody shouting from one direction, another person shouting from another direction, there's a Twitter fight going on, and so on and so forth.

If you look at the Chinese official media system, it's extremely orderly. In some ways it's really simple, therefore, to go through and to navigate through.

When I then step back and look at the Indian media ecosystem, which I used to be a part of for over a decade, I end up finding it really disconcerting. [After looking at Chinese media,] it's really disorienting to then look at normal media ecosystems.

I've sort of enjoyed the order, which is blasphemous for a former journalist to say.

Jordan Schneider: You alluded earlier to the fact that the People's Daily is what the party wants you to see. What can and can’t you learn from an exercise like this?

Manoj Kewalramani: I'm not going there for news per se.

The front page doesn't really tell you anything about what's happening in the world or even what's happening in China.

You could have had a massive flood. You could have had a blast somewhere. It would make the front page of newspapers in most places around the world. But the People's Daily will still print a picture of lovely snow or Xi Jinping plastered across the front page.

You don't necessarily go there for news. It doesn’t give you that. What you go there for is essentially what the top leaders are doing and saying. You also go there for the ideological tone that's being set. If you looked at the past year, a lot of the focus was on the history learning campaign that was being run, for example.

You saw the introduction of much more language which spoke about redness and red heritage and all of that. So you see that the general tone of commentary is changing.

Essentially, you get a sense of the party's priorities: political priorities, economic priorities and the sort of ideological line that the party wants to set, based on which you'll see policy formulations coming down the road.

I don't necessarily go there to look at granular things about social policy, economic policy and things like that.

Jordan Schneider: How do you think the Xi-era People's Daily ranks in entertainment value compared to previous People's Daily eras?

Manoj Kewalramani: There is absolutely nothing that's exciting. There are moments where you will find a piece like, say for example, earlier this year, there was some talk about push back against Wolf Warrior diplomacy.

It said something about creating an image of China that is lovable, and at the same time, there was very long commentary which mentioned how Zhou Enlai’s diplomacy in the 1950s expanded China's circle of friends.

When I was reading through that, my first thought was about whether this was somebody telling Xi Jinping that you need to go back to far more personable diplomacy rather than what you're doing right now.

But the other interpretation, which I think is probably much more accurate, is that this was basically saying that we need to focus on the developing world much more, which I think subsequently propaganda and policy suggest that that's where that's going.

The state of open source research on China

Jordan Schneider: What is your take on the kind of overall quality of CCP document-driven, open source research outside of China today?

Manoj Kewalramani: It's really poor. It's a really underexplored area and one of the reasons why I started eventually putting this out as a blog and I spend two and a half, sometimes three and a half hours, going through different things.

I increasingly realized that in India, there's very little focus on what the party is saying about itself and to itself. We aren't necessarily looking at that. In the West, particularly the US, there is far greater focus on that, but still it's insufficient.

In the US, Congress has been looking to create some sort of support for open source work and translation of documents, but there's so little that we do with so much that's available. I think there's so much more scope to do this.

There’s official newspapers and publications and documents that the party’s putting out, but there's so much more.

There's so much more analysis by Chinese academic scholars which we don't look at at all. Part of the problem also is that if you're only looking at official readouts and official publications, even just the People's Daily, you miss the diversity of thought that exists in China.

And then you start to believe that there's a hegemony of thought and there's a unified thought and everything works according to that, which is not necessarily true.

There's clearly much more debate than we assume there is. It's just that it takes place in forums that none of us seem to want to access, even though it may be accessible.

Jordan Schneider: It's a few things. Even if you have Chinese, [reading official documents] is a whole other set of vocabulary.

You talked about how boring it is and that folks have to get over that. But it's also that there's not a business model for doing this.

In undergrad, you can major in political science, you can major in history, you can major in international relations, but even a China studies degree will not let you take 12-week courses on how to do this.

How did you personally build this muscle?

Manoj Kewalramani: I think it was just consistency and looking at one thing and doing it on a regular basis. I'd be the first person to admit that my language skills leave much more to be desired. But you can keep up-skilling and there are tremendous machine translation tools out there, which can do really good work to at least give you a gist of what's being said.

As you do things more consistently, you start to get a sense of the cadence of the documents. What are the purposes of different sections? Why are certain changes relevant, why are certain changes not relevant, which documents matter more than the others?

The other thing that I think is important and a lot of this gets to why this open-source work is tricky and difficult is that it's not just language. It's not just understanding the Chinese political ecosystem and political economy. It's also having a sense of strategic affairs, how bureaucracies work, how international relations work. I think that's really, really useful.

Work in this sense happens in silos where people are Chinese language experts who are translating these documents yet they don't necessarily have the sense of political economy or elite competition to be able to interpret them at the same time.

You have people who maybe have that sense, but don't have a sense of how bureaucracies work.

And then you've got sort of strategic affairs to look at why some things are being done within the broader context of changes taking place between countries in the world order and so on and so forth.

That's the holy grail for me. That's what I'm trying to get myself towards, where I can bring some sort of a mixture of these different skill sets.

Manoj’s 12 step program for understanding the Chinese political ecosystem

Jordan Schneider: I'm trying to formulate what the sort of like Coursera version of this is, and maybe we'll find a funder and put it out for free. What is the 12-week course that gets folks started on this as a practice?

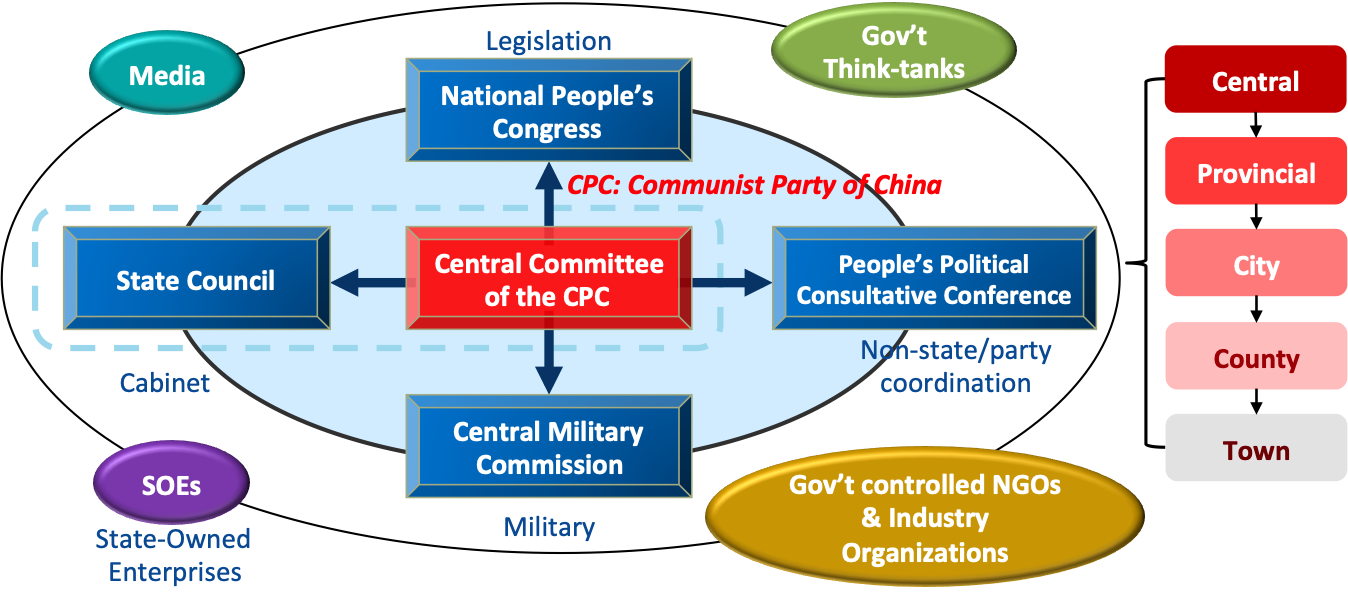

Manoj Kewalramani: I think the first session would just be to understand the different departments that exist within the communist party and the state system, just get a sense of the ministries, the departments, which are the important positions.

First, get that type of framework in place. After that, we look at the policy ecosystem. Get a sense of which department does what. So for example the first session would be about what the keys to control power are.

Then we’d look at who does what. What is the role of the Ministry of State Security or Ministry of Public Security? What is the role of the Cyberspace Administration?

Then how is all of this structured and what are the rules of each of these entities? How do they interact with each other?

I'd also look at the media ecosystem because I think the propaganda element is extremely important. There are different publications focused on different issues, right?

You've got the People's Daily, you've got Economic Daily, you've got Security Times.

You've got all of these different entities which are doing different things. What is the authoritative nature of each of them? Where do you go for what?

Then we come to what are the kinds of documents that you want to look at? The speeches given by the top leadership are the first thing that I would look at.

I would also look at are readouts from Politburo meetings and Politburo study sessions or the PLC sessions. Those are your documents. Those are going to guide policy, going to set the frame for where things need to go.

Then we come down to guidelines and opinions which are usually issued at the highest level by the Central Committee and the State Council together. These are really long, somewhat abstract, some often very repetitive, boring documents.

But they're really, really useful because if you just look at them there's a bit of a preamble after which you have something called guiding ideology - which you'll never find in say the American system or the Indian system - where the highest authorities are issuing something which says that your actions need to be guided by XYZ ideology.

That tells you a little bit about the power dynamics within the party. It tells you a little bit about the approach that the party has taken to a particular policy going forward.

Then you have the principles that this document needs to meet. Then you have specific goals and targets. I'm saying specific, but they can be quite abstract because it will be something like by 2025, we need to get here. By 2035, we need to be the best at this domain and we need to have achieved everything and the world will be civilized and everybody's going to be happy.

And then you have the pathway to get to that. Again, these are fairly high level abstractions where it'll be like to be able to achieve carbon peak carbon neutrality, or to be able to maintain supervision with regard to the implementation of carbon peak targets, we need to use AI for supervision.

We need to use technology. We need to use this and use that. So you'll see sort of pathways without necessarily clear direction. For that you come to one level lower, you have obviously laws which are eventually passed, but you also have regulations and rules.

Jordan Schneider: What would your homework assignments be?

Manoj Kewalramani: I think there are different things. So I would want to give some assignments that would essentially look at elite politics and the political implications of what's being said.

If you're reading through speeches by Xi Jinping or speeches by other senior leaders, or if you're reading through readouts from Politburo meetings, I would want you to look at the dynamics of the politics.

What's the kind of message that's being sent? Often this communication is also external signaling. What are the signals that you're deriving out of that?

I'd also want them to look at some of these fairly high-level abstraction guidelines, then I would want them to take that and go and look at what the different departments ministries have said, how they've interpreted these.

Sometimes they interpret these very differently. What was said and how was it interpreted and what was the eventual outcome on the ground? If you can create that flow chart, that's a really excellent takeaway.

I want folks who are studying this to be able to make those connections and to see where things move in translation, how local interests play a role in them being adapted and so on.

Jordan Schneider: I think it's really important. There are two things that are sad. First, doing this is not necessarily a way to support yourself. For the people who do this, for a lot of them it's just for the love of the game, and this is stuff you do in the morning or late at night where you have your other job, which is not necessarily focused on reading party documents. So that's the one sad thing, which I don't think one course can fix.

But in the meantime, to fill that gap there is an appetite among young China watchers to be able to build this muscle, to do this sort of stuff. But the resources just aren’t there, which is a bit of a tragedy, especially just considering how people always talk about how we need to understand China better.

Academia and the vast majority of the think tank world I think has largely failed in giving folks the baseline understanding of the party that they need to do some of this really important work.

And, as you said, you're really not going to get it from journalists, who have to write five articles a week and don't really have the time to do this sort of very detailed, not particularly sexy work of reading through these party papers and documents.

Manoj Kewalramani: For people to go into primary research, it's becoming increasingly more challenging. On one level, this is a massively important research resource for people to go and use at another level.

Because China is getting more closed, you need to exercise this muscle much more while looking at policy implementation to be able to understand what exactly is happening in the country. Even if it’s just to get a sense of what's happening in the country, because without having boots on the ground, it's going to be much more difficult.

As that sort of challenge grows, I think it's important for folks to fund this sort of work.

Jordan Schneider: It's particularly dangerous, I think, in an environment where people are always assuming the worst out of the CCP, and Xi in particular. Sometimes that may be justified. Sometimes it won't be.

But if your bias is towards seeing things as an aggressive expansion as power which is going to take over the world and you have no other inputs which could potentially check that, you're just going to fall into this sort of circle of confirmation bias, which is dangerous if you're actually wrong.

Want more? The full interview with Manoj is available here.

Does the lack of resources available to learn about how to do open source research on the Chinese government and institutions keep you up at night? ChinaTalk is looking for funders who can support us in developing those resources. Please get in touch!

Thank you for reading. ChinaTalk grows only through word of mouth. Please consider sharing this post with someone who might appreciate it.