Huawei Banned, So Let's Invade Taiwan to Take TSMC?

On May 15, the Commerce Department announced a set of strict new rules that intend to cut Huawei off from the global semiconductor ecosystem. The rule changes set WeChat abuzz with what to do next.

Proposed responses range from calling for a massive national project to catch up in semiconductor technology to encouraging a new generation of Chinese to rewrite the rules of global governance.

A disconcerting number of articles suggest, at times as a casual aside, that Huawei’s problems would disappear if China takes control of Taiwan, and with it TSMC, the world’s largest contract manufacturer of semiconductors.

Ning Nanshan, an anonymous Shenzhen-based commentator who posts on his own blog about Chinese industrial and economic development, argues that Huawei will be able to buy cutting-edge chips that are free of American technological components in a matter of years, but that in the meantime Huawei’s business can survive in order to maintain China’s dominance in 5G. His article published last week received a few hundred thousand views.

Ning looks at three questions: 1) What capabilities does Huawei need to develop in-house or cultivate domestically over the next few years in order to achieve full “de-Americanization” of its core businesses? 2) What measures should Huawei adopt in order to make it through the intervening years before it is able to get cutting-edge chips through a wholly de-Americanized process? 3) What should China do to punish America for trying to throw Huawei off its dominant position in 5G?

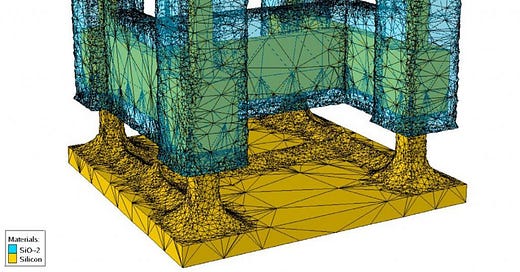

After explaining the ways in which the new measures go further than the previously adopted American Huawei ban, the author examines how the new restrictions will impact Huawei’s access to Electronic Design Automation software (a tool necessary to eliminate errors and cuts cost associated with designing chips, see here for why China is lagging behind in this area), to the basic architecture needed to design chips, and to foundries that can fabricate chips.

The following abridged translation is by Cody Goldberg.

In this week’s podcast, check out an interview I did with some researchers out of Georgetown’s CSET on how China’s AI research budget stacks up with America’s and why it matters.

A Brief Discussion of America’s Huawei Ban

Ning Nanshan, May 20th, Self-published

In order to meet the software needs of future chip design, Huawei should develop its own Electronic Design Automation software. China’s largest company capable of proving EDA tools, Huada, may not be up to the task of meeting Huawei’s needs. HiSilicon is currently using older EDA software for its chip design, but the task of developing new EDA software is no longer insurmountably difficult. Huawei seems to have already taken steps to this end.

A pretty visualization from Synopsys, one of America’s leading EDA firms

HiSilicon’s chips, meanwhile, are built using ARM’s chip architecture. It is important to note that ARM is not even an American company; the UK-based company is owned by Softbank, and has been willing to cooperate with Huawei in using legal means to circumvent American bans in the past. In fact, though ARM initially indicated that it would sever its Huawei connections in May 2019, it reversed course in October after determining that its chip architectures were of UK origin. However, ARM has R&D facilities in Texas and California, and much of its technology has American origins. Therefore, ARM will be unable to provide Huawei with further technical services or cooperation due to the new U.S. measures.

However, Huawei has already obtained permanent authorization to use ARM’s v8 chip architecture. It can modify designs based on ARM architecture to meet the needs of its own processors. After being modified by Huawei (or more specifically, by HiSilicon), can ARM architecture chips still be called an American technology?

Huawei is already deeply invested in building a technology ecosystem around chips that use ARM architecture. As part of its long-term strategy, I believe Huawei has already established autonomy from ARM with regard to the chips built on the UK company’s architecture and has already assessed the risks of facing U.S. sanctions from a technical and legal standpoint.

The next step for Huawei is to work in conjunction with domestic partners to develop its own EDA capabilities, and to continue to develop chips based on the ARM architecture.

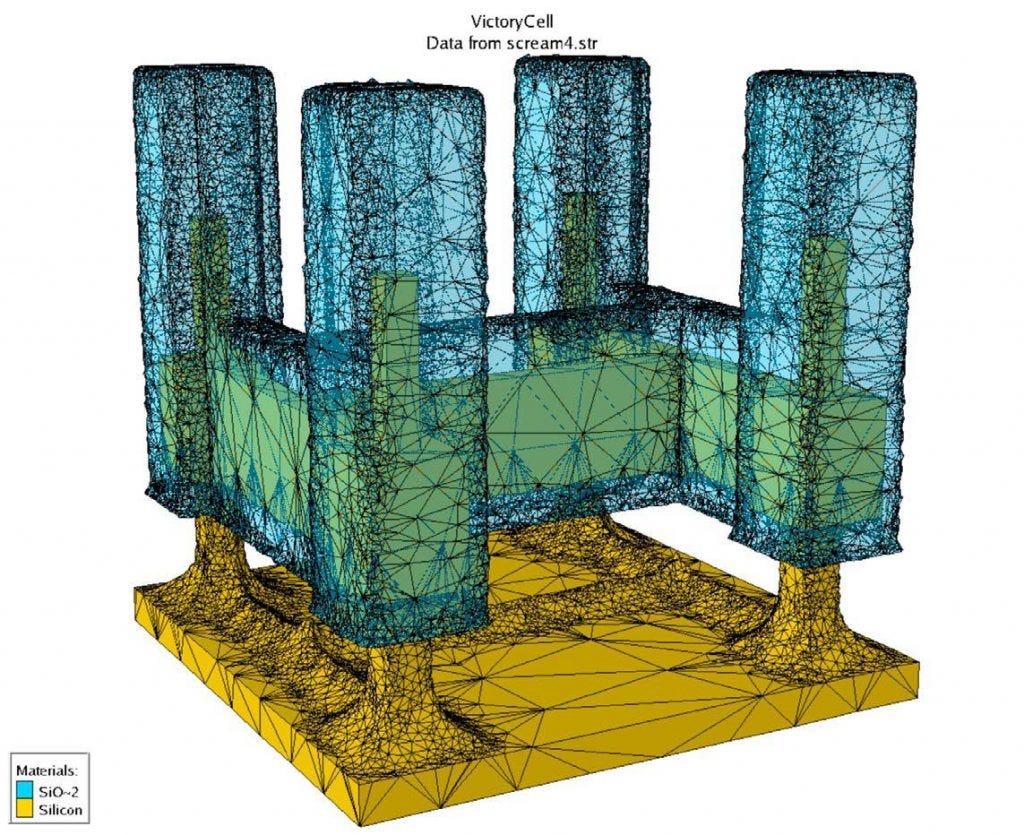

Another type of newly restricted products are chips produced according to the design specifications of Huawei and HiSilicon. Any chip foundry [a semiconductor OEM] that uses equipment on the American CCL list is required to obtain a license to continue selling to Huawei or its affiliates. This rule is clearly aimed at TSMC, the world’s largest semiconductor producer, and will also affect Samsung, SMIC, and Huahong. The restrictions will even affect sales of chips produced at foundries in China, such as at TSMC’s Nanjing foundry or SMIC’s mainland foundries.

Some relevant background information about TSMC:

On May 15, the same day that the U.S. announced its new restrictions on Huawei, TSMC announced plans to build a 5-nm fabrication facility in Arizona. TSMC is not moving manufacturing to the U.S. of its own accord. It has no choice but to cooperate with America, which wants a greater degree of supply chain control in the semiconductor industry. The U.S. has been having the same conversations with Samsung and Intel, too, asking that all three manufacturers move more fabrication to the U.S. [See last week’s issue on why TSMC’s Arizona foundry is likely to underwhelm.]

TSMC, which has the world’s most advanced semiconductor technology, is particularly critical to these plans. Should China unify in the coming years, Chinese semiconductor production capabilities would jump lightyears ahead, not only eliminating the “Huawei dilemma” we face today, but also eliminating any future possibility of advanced fabrication shifting to the United States.

The U.S. has not yet mastered the 5nm fabrication processes, so it forced TSMC to build a facility in Arizona in order to obtain the capability.

TSMC, however, is intent on keeping its production primarily in Taiwan. It currently has three fabs outside of Taiwan — one in Washington state, one in Shanghai, and one in Nanjing. 90% of the total output comes from the Taiwan plants. Moreover, the Arizona plant will no longer be technologically cutting edge by the time it is completed in 2024, by which point TSMC will have the capacity to do 2-nm fabrication in its Taiwan foundries. The Arizona fab will have a capacity of 20,000 wafers per month, the same as the Nanjing facility, though the Nanjing foundry produces an older technology than 5-nm.

Okay, now to return to America’s ban:

Huawei still has 120 days to obtain supplies from TSMC and other foundries, but after that the foundries cannot continue to supply Huawei. In theory, Huawei could urge suppliers to increase production over these four months to help it stockpile more chips.

But what will Huawei do after May 2020?

As discussed earlier, Huawei must use fully self-developed EDA software to design chips and must identify foundries for chip fabrication that do not use American equipment or technology. The EDA will be completed by Huawei’s own research in concert with other domestic partners. This was already a strategic project that Huawei was working on because EDA software had become difficult to obtain after America’s initial Huawei ban in 2019. Finding a foundry that can produce wholly de-Americanized chips will require the cooperation of a domestic foundry, making use of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and European technology. Both of these steps will take time, probably a number of years.

So how does Huawei buy that time?

1. Prioritize the use of chips for the delivery of 5G base stations.

The U.S. has not attacked Huawei because Huawei is the second-largest smartphone maker in the world, but because Huawei is the global leader in 5G technology. Therefore, Huawei’s chip stockpile must be used first and foremost to supply the needs of its 5G bases.

Meeting this demand should not be difficult. The number of base stations globally is in the tens of millions, constituting a small source of demand compared to the billions of mobile phones in the world. Nor will Huawei be building every single base station. Therefore, it is fully feasible to meet the chip demands of 5G base stations. In China, for example, there are expected to be 550,000 5G base stations built in 2020. Huawei can stockpile the millions of chips needed to build these base stations.

It is also important to note that because Huawei already provides 2G, 3G, and 4G services to more than 100 countries around the world, it is impossible for the United States to completely prohibit fabrication on behalf of Huawei. It will at least have to allow for the supply of chips for maintenance of existing infrastructure, lest it pose a threat to the network stability of many countries.

Of course, the mobile phone market is a different matter. Huawei shipped 240 million units in 2019 and supplying these phones with chips will be difficult under present conditions.

2. Use non-U.S. chip manufacturers not affected by the U.S. government’s announcement that will still be able to sell chips to Huawei.

According to an IHS Markit report, the proportion of Huawei phones equipped with Qualcomm chips fell from 24 percent to 8 percent between 2018 and 2019, while the proportion equipped with MediaTek chips rose from 7 percent to 16.7 percent. Low-range and mid-range chips can be purchased from domestic and other non-U.S. chip manufactures, while Huawei relies on current stockpiles to meet its needs for high-range chips in the interim.

3. Diversify Huawei’s business, using other revenue streams to shore up the company while its core business is limited.

In May 2019, Huawei announced the establishment of a department working on smart car solutions for car manufacturers. This is a huge market that Huawei can tap into. According to the company’s growth plans, the smart car solutions market will be one of its major areas of growth in the future, accounting for fifty billion dollars in annual revenue by 2030. Other revenue streams that do not rely too heavily on chips include Huawei Digital Power — a Huawei division that helps telecom providers improve energy efficiency, and saw orders in excess of thirty billion RMB in 2019 — and Huawei Smart Home.

These business lines do not need chips of the same advanced technological degree required by mobile phones, and thus chips fabricated by domestic foundries or by HiSilicon could meet Huawei’s needs. After all, domestic lithography machines can achieve 90-nm fabrication, which means that HiSilicon could build a de-Americanized fabrication line with relative ease. Less advanced chips account for a sizable portion of the market — in 2019, SMIC earned more than half of its revenues from wafers of 90-nm or lower (meaning a lower degree of advancement, a number higher than 90-nm).

4. Accelerate the development of wholly domestic fabrication plants under SMIC and Huahong, and promote the development of upstream equipment manufacturers.

At present, it would not be viable for domestic manufacturers like SMIC to supply Huawei in violation of the U.S. ban. SMIC is still in a technological and production capacity building phase. Although it can now produce 14-nm chips, its production capacity will only reach 15,000 wafers per month by the end of 2020.

In order to catch up with international competitors, SMIC has invested a lot of money in equipment procurement. In 2019, it spent 600 million dollars to purchase etching machines from Lam Research and spent 540 million dollars to purchase new machines from Applied Materials Group.

It also announced that the China National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund and Shanghai Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund would be investing 1.7 billion dollars and 750 million dollars respectively into SMIC Southern, a subsidiary of SMIC. 40% of the new capital will be used to expand production capacity.

SMIC and Huahong should not risk incurring U.S. sanctions by supplying Huawei. So long as Huawei sticks it out for another two or three years, domestic semiconductor fabrication will see a major breakthrough.

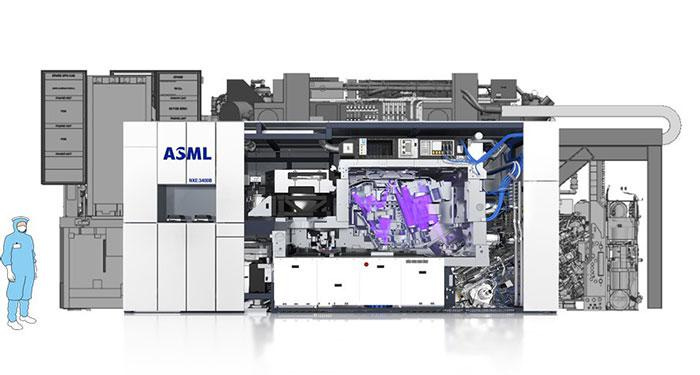

Domestic companies are currently developing their capabilities to create the equipment needed for semiconductor production. In areas where China is currently most behind, there are companies engaged in intensive research. For example, Shanghai microelectronics is working on lithography machines and Beijing Zhongkexin and Kaishitong are working on ion implantation. Lithography machines are of particular concern, so as part of the 13th five-year plan which concludes this year, Shanghai Microelectronics is expected to release a 28-nm lithography machine. If the 28-nm lithography machine can be successfully produced during its trial period in 2021, mass production can begin by 2021 or 2022, enabling China to develop a fully de-Americanized 28-nm processor using only domestic, Japanese, and European equipment.

ASML’s lithography machines cost over $100m and Chinese firms can’t figure out how to make them. I quite enjoyed Engadget’s intro to EUV lithography which takes a tour of Intel’s Oregon fab.

Of course, 28-nm processors will not be sufficient, and development on more advanced lithography machines is already underway by domestic companies. For mobile phones, 14-nm processors are often required. Base stations have a lower requirement threshold (i.e. a higher nm).

Now, a final word. The strategies that Huawei can adopt to survive have been thoroughly analyzed. Huawei will survive these dark moments and support the growth of domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

While the localization of semiconductor fabrication develops over time, the main question is not whether or not Huawei can survive. Despite a few hard years, Huawei will certainly survive. The main issue is supporting Huawei in maintaining its dominant position in 5G and helping it continue to be able to supply the needs of 5G bases.

In addition to stockpiling goods and accelerating the localization of the semiconductor manufacturing process, this requires a national counterattack. Although it is difficult to force the United States to lift the Huawei ban, China has two paths open to it: China can make America companies feel the pain, and, more importantly, China can adopt measures to hinder the development of 5G technology in the United States. Any companies that can help America achieve its goals in terms of 5G development should be the targets of this counterattack.

For the first line of attack, Boeing is a good target; for the second line of attack, Qualcomm is a good target. Apple also fits the first target, but Apple’s supply chain is deeply tied up with China, so targeting Apple would also harm China.

Please consider donating to ChinaTalk’s Patreon.