Is China’s model of economic development compatible with democracy? Were events like Tiananmen Square and the rise of Xi Jinping inevitable under China’s governance structure?

Welcome back to part 2 of our interview with Yasheng Huang 黄亚生, the author of The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline.

In this installment, we discuss…

The aspects of imperial China’s governance Mao chose to embrace, and those he chose to abandon,

The factors enabling Mao’s radical policies compared to imperial rulers,

Why China was able to grow so much faster than India, despite the setbacks of the Cultural Revolution,

Statistical approaches for evaluating the effectiveness of autocratic development models,

China’s economic reforms and rural development policies in the 1980s,

How the events of 1989 permanently altered China’s trajectory,

Whether the rise of Xi Jinping was inevitable.

Apple Podcasts:

Spotify:

Co-hosting today is Ilari Mäkelä of the On Humans podcast. Here’s part one if you missed it.

Mao’s China — Dynastic Traditions and Leninist Innovations

Jordan Schneider: Last week, we discussed Chinese history up to 1949. Ilari, could you give us a brief recap of our first episode?

Ilari Mäkelä: To understand China’s history, Yasheng Huang emphasizes the importance of focusing on the little-studied period after the collapse of the Han dynasty in the third century. During the next few centuries, China resembled Europe, with no single power base and competing ideologies. Huang’s studies have shown that this was also when China was at its most inventive.

Unlike Europe, this political fragmentation ended when China was unified again in the 6th century under the Sui dynasty. Everything changed with the introduction of civil service exams on a large scale. These exams allowed a significant portion of the population to participate and created stability. Many Chinese believed that through hard work, they could gain political power.

While this system prevented the development of a European-style aristocracy, it funneled all intellectual efforts into serving the emperor. Consequently, there were no power struggles like Henry VIII versus the pope, nor was there an Enlightenment-style intelligentsia. Instead, China produced numerous Confucian-educated civil servants.

Jordan Schneider: Professor Huang, what aspects of this imperial tradition did Mao adopt or reject when he began to rule in 1949?

Yasheng Huang: Mao took over China in 1949, inheriting certain aspects of imperial China while departing from others. He maintained and extended autocratic controls, implementing strong economic controls through central planning, state ownership, and government price-setting. Politically, communist China’s power reached beyond the county level, extending to villages through land reforms and the communist system.

However, Mao actively went against imperial tradition by de-emphasizing bureaucracy and meritocracy. This shift began in 1957 and intensified during the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Universities were closed, examinations and expertise were downplayed, and ideology was elevated. While ideology was important in imperial China, Mao’s approach differed significantly, relying on political and ideological studies rather than the traditional examination system.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting that you argue the more codified a system is and the fewer power bases that exist, the more important the leader’s actions become. However, even powerful Ming or Song dynasty emperors couldn’t have executed the level of radical changes that Mao implemented from the mid-1950s through the end of his reign. Mao seemed to combine the worst of both worlds — centralized personal power without bureaucratic and cultural safeguards that would have prevented disasters like the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution.

Yasheng Huang: Excellent observation, Jordan. Two additional factors contributed to this difference.

Modernity — imperial China lacked modern means of transportation and communication. Indoctrination was the primary tool, and once officials were dispatched to remote regions, central control diminished. In contrast, modern systems allow for instantaneous and ongoing control through air travel, trains, and buses, facilitating frequent indoctrination sessions in Beijing.

Transformative agenda — imperial China, like many traditional polities, focused on maintaining the status quo. They often lacked knowledge of potential transformations or how to preempt them. Mao, however, had a highly transformative agenda. In 1958, he famously aimed to surpass Britain and America in steel production — a concept foreign to Ming dynasty emperors.

Communist China was more ambitious and transformative, aided by Leninist techniques and organizational capacity. It wasn’t a carbon copy of imperial China, but incorporated elements borrowed mostly from the Soviet Union.

Vladimir Lenin’s theory of the vanguard of the revolution emphasized the ability of political elites to rapidly transform society. While Karl Marx predicted that communist revolutions would occur after capitalism, Lenin argued they could be launched directly from feudalism. This transformative agenda was absent in imperial China but central to Mao’s rule.

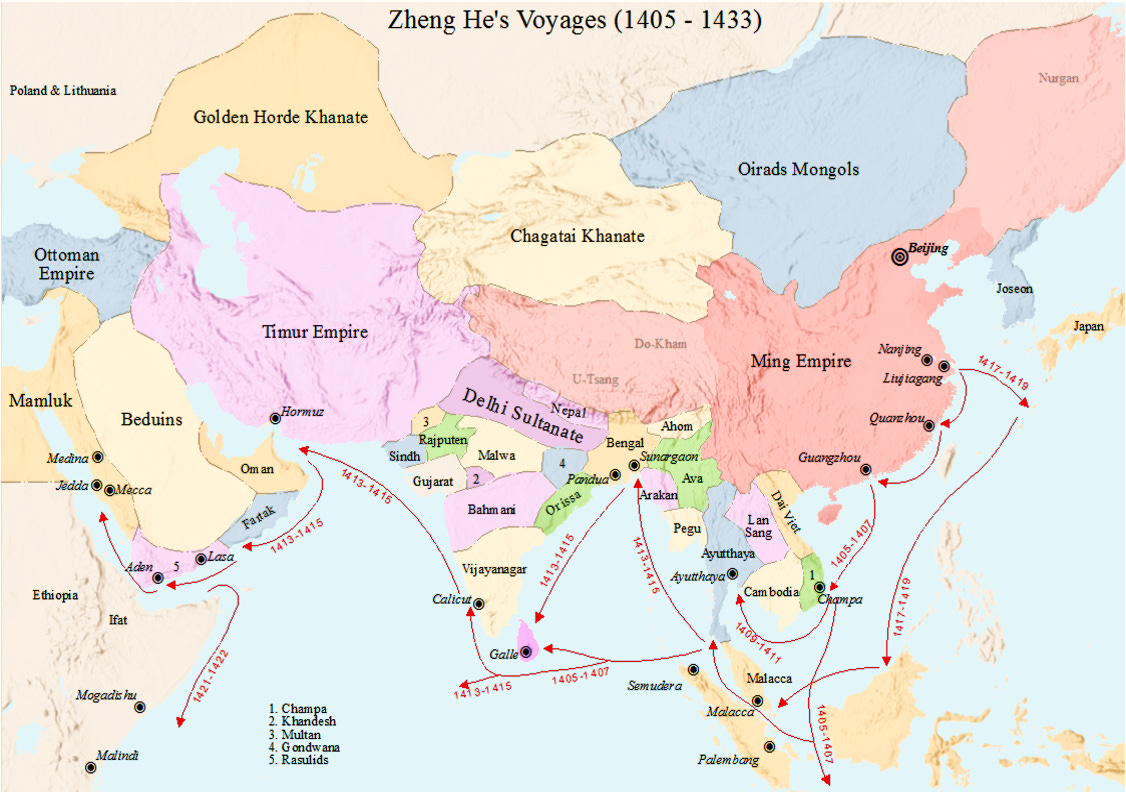

Jordan Schneider: The contrast between the Ming dynasty and Mao’s Leninism is fascinating. You argue that when Marco Polo arrived in Yuan Dynasty China, he felt transported 500 years into the future. During the voyages of Zheng He 鄭和, the Chinese viewed other cultures as backward and lacking.

Human nature may play a role here. When elites feel they’re at the top and things are stable, they may be less inclined to explore, change their minds, or question whether their system has all the answers. In contrast, from the fall of the Qing dynasty through the Republican period to Mao’s era, there was a keen awareness that China needed to catch up with the rest of the world.

To what extent is this perspective determined by China’s relative position as more or less advanced than other societies?

Yasheng Huang: I agree that the factor I mentioned is one of many contributing to this perspective. However, even given the disparity between East and West 500 years ago, it doesn’t fully explain China’s isolationist stance. The mental model you describe likely applies to the political elite who, upon seeing nothing impressive abroad, decided to remain insular.

Today, people from wealthy countries often explore poorer regions out of curiosity. When Christopher Columbus embarked on his voyages, he had personal motivations and potential gains alongside nationalistic agendas. This personal stake was entirely absent in Zheng He’s voyages, which were purely state-sponsored activities with national objectives.

Jordan Schneider: That’s an apt comparison. European colonization in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries — despite the lack of respect for native populations — still involved scientists and observers who documented their experiences. This information flowed back into the broader ecosystem. In contrast, China lacked this type of engagement for over a thousand years.

Autocratic vs Democratic Development Strategies

Jordan Schneider: Ilari, would you like to bring us back to Mao?

Ilari Mäkelä: One interesting aspect is the package Mao inherited from the imperial era (albeit in a mutated form) is the autocratic tradition, which we often view as partially negative.

One of the most fascinating questions in comparative economics is why China has grown so much faster than India. Some argue that democracy doesn’t work well for such a large country as India, suggesting that autocracy, like in China, is necessary. You have a different perspective, focusing more on China’s human capital resources.

I recall you mentioning in your TED talk that China grew at a pace similar to or even faster than India, even during Mao’s era. This suggests that growth occurred despite policy, not because of it. You attribute this to an inherent push for growth in China, absent in India, linking it primarily to literacy. Is this correct?

Yasheng Huang: The baseline judgment on China and India is based on almost a single data point from the World Bank website — the GDP per capita of China and India in 1980 or 1990. It shows that India had a higher GDP per capita than China at that time. Twenty or thirty years later, China’s GDP per capita surpassed India’s. Many people used this data point to argue that autocracy (China) could grow faster than democracy (India).

However, there are a couple of problems with this conclusion. First, the data is almost certainly wrong. One issue with Chinese GDP data is that they used a Soviet system called the material product measure, which didn’t include the service sector. In poor countries without industrialization, you have agriculture and a sizable service sector. For many years, the service sector was very large in the Indian economy.

Ilari Mäkelä: But isn’t it still true that China has undergone a more dramatic transformation than India since the 1980s?

Yasheng Huang: Absolutely. The point I was making earlier disputes the initial discrepancy. Given that China grew faster than India, it’s actually more impressive if you believe that China started from a higher per capita base. However, there are many differences between China and India. It’s puzzling why people immediately jump to the conclusion that it was because India was a democracy and China was not.

To properly evaluate this, we need to look at global evidence to compare at least two competing hypotheses, which are human capital and the political system. Academic literature increasingly shows that autocratic and democratic systems don’t have a significant impact on growth rates. Some autocracies grow very fast, like China, Taiwan, and South Korea in the 1960s and 1970s. There are also spectacular failures, such as the Philippines, Indonesia, and many African countries.

The problem with the formulation by many Chinese and some Western intellectuals is that they escalate a factual statement about China growing faster than India to a statement about the superiority of autocratic systems.

When discussing systems rather than specific countries, you need evidence from other countries with the same system as China. That’s just common sense.

Jordan Schneider: Where do you think this argument comes from then?

Yasheng Huang: Some people believe in autocracy and are grasping for evidence to show their belief has economic benefits. I often point out to them that China was also autocratic under Mao, but it didn’t grow very fast during that period. An honest person would conclude that there must be something else different between Mao and Deng’s eras. Perhaps globalization, open policies, or private sector development played a role.

I’m dissatisfied with media coverage because they often go for sensational statements without examining the logic behind people’s views. In academic seminars, these arguments wouldn’t hold up for five minutes because basic logic would demolish them. Unfortunately, media attention often goes to those making broad, sensational statements rather than those presenting logical arguments and evidence.

Liberalism and the Future of Chinese Democracy

Ilari Mäkelä: One reason for the hyperbolic “it’s because of autocracy” conclusion might be that some Westerners have inadvertently contributed to this by repeatedly claiming that autocracies cannot grow fast. When faced with a fast-growing autocracy, it’s easy to jump to the opposite extreme conclusion. Would it be fair to say that there are certain conditions under which autocracies can grow fast? For China, factors like the imperial legacy of civil service exams (Keju) leading to high literacy and human capital, and a post-Mao autocratic political environment that was more conducive to growth due to increased pluralism and diversity, played significant roles?

Yasheng Huang: That’s a very good observation, Ilari. In my current book, which is a revision of my 2008 book, I argue that the right way to look at China or any country is to focus on the direction of movement rather than static conditions. That is, we need to look at whether the is country moving towards more openness or more closure.

It’s not accurate to say that China couldn’t grow because it’s not a Western democracy, or that it could grow because it’s not a Western democracy. The key is to look at the movement of both Eastern and Western countries. Are they moving in an open or closed direction? In statistical terms, this is called a difference-in-differences approach.

Under Deng Xiaoping, China was undoubtedly an autocracy, but it was moving away from Mao’s totalitarianism towards a more authoritarian society. For people living there, this shift made a huge difference. The incentive effect comes from that movement.

Imagine an entrepreneur in 1978. They wouldn’t be deterred by the lack of Western-style institutions. Instead, they would be encouraged by the fact that they could now start a business without fear of arrest, unlike in 1976. The incentive effect came from China becoming less autocratic, not from being autocratic.

As a policy question, the real issue is whether to move the country more towards or away from autocracy, even if the decision isn’t about fully embracing democracy.

Jordan Schneider: Can we relate this to your personal history? If you were born five or ten years earlier, do you think you would have even bothered learning English? How did this change in the political climate reflect in your youth, particularly in terms of learning and the drive to acquire knowledge?

Yasheng Huang: In my personal case, I was always interested in knowing more rather than less, regardless of the environment. After coming to the US, I spent hours in the library reading Western writings about China, particularly about the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward, because I couldn’t access that knowledge in China.

Regarding business motivations, people need to feel secure to make investments. If you know you’ll be arrested immediately after making an investment, you won’t do it. In my book, I emphasize the importance of not underestimating the incentive effect of not being arrested. Many people focus on China’s lack of secure property rights law, neglecting the fact that Deng Xiaoping significantly increased the personal security of the Chinese people. This increased security was a crucial factor in encouraging Chinese entrepreneurs to start businesses.

Ilari Mäkelä: The era after 1978 is indeed special and quite different from everything else that happened under the CCP. There wasn’t a significant rural-urban gap at the time, with rural areas growing as fast as urban areas. There was also a diversity of voices within the party, ranging from old-school economic planners to reformers like Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳. Since you lived in China in the 1980s, could you share your personal experience of that period?

Yasheng Huang: I first came to the US in 1981, but I returned to work for the World Bank in China during the 1980s. However, my understanding of that period didn’t come from my lived experience. Like many Western observers, I didn’t have a clear view of the 1980s until I began working on my 2008 book.

After publishing a book on foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2003, I was left with the question — what was driving Chinese growth in the 1980s, before FDI became crucial? This led me to research the 1980s extensively for my 2008 book, Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics, which is also summarized in my 2023 book.

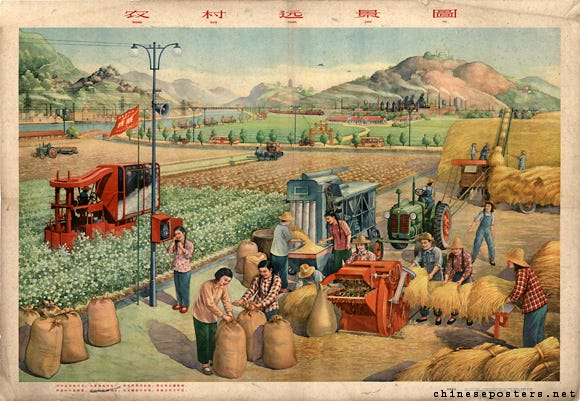

I discovered that reforms in rural China went far beyond agricultural reforms. There were contracting reforms, land reforms, village elections, and even rural financial liberalization. I was astonished by how proactive the Chinese leadership was about rural financial liberalization. Top officials from various banks were issuing support for these reforms.

Large-scale financial institutions developed extremely fast in rural areas during the 1980s. This affected 800 million people, as China was 80% rural at the time. Yet, Western scholarship largely ignores this period. The prevailing narrative is that China grew without financialization or with a state-owned financial system, disregarding the extensive documentation and statistical analysis showing otherwise.

It’s frustrating and saddening that there’s so little curiosity about this crucial period in China’s development, despite its immense impact on hundreds of millions of people.

Ilari Mäkelä: You’ve piqued my curiosity. Before we discuss what happens next and why this trend doesn’t continue, I’d like to ask a question. I mentioned earlier that one of the interesting aspects of the ATS is that it’s not always a matter of the CCP making decisions based on a grand strategy. Often, it’s because there is no grand strategy. There are internal power struggles, such as Deng Xiaoping versus Chen Yun 陈云, or Zhao Ziyang versus Li Xiannian 李先念. Based on your research into those documents, to what extent was this a unanimous decision in Beijing versus the liberal factions of Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 and others being able to operate under the cover of confusion?

Yasheng Huang: People like Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang didn’t suddenly decide to implement financial liberalization. What’s remarkable about 1980 is threefold.

There was political fragmentation at the very top, as you mentioned.

The policy ethos was focused on tangibly improving people’s lives rather than solely on GDP growth. Any policy or practice that improved people’s lives was considered the right approach by definition. For example, small-scale sellers on Beijing streets selling chickens and various goods were allowed because it improved their lives by providing income.

There was a prevalence of initiative-taking. A concrete example is the Rural Credit Foundation, an almost national-scale rural financial institution. The central bank refused to recognize it, fearing disruption of financial control. However, the Minister of Agriculture stepped in and provided legitimacy. Such local bureaucratic initiative is unimaginable in China today or even in the 1990s.

These practices weren’t initiated by Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang, or Hu Yaobang. Deng Xiaoping famously said about township and village enterprises, “The Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party takes no credit for it. It was a total surprise to us.” Essentially, there was space for organic and spontaneous practices, which almost entirely disappeared, especially in rural China, after 1989.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss 1989 then. You have this concept of axiomatic legitimacy, where after 1500 years of imperial rule over the broader Chinese landmass, people expect and defer to the legitimacy of the center, except during rare occasions like dynastic falls or major invasions. Professor, to what extent do you believe a counter-revolutionary reaction was inevitable?

Yasheng Huang: I don’t believe 1989 was inevitable. I concede that China’s post-1989 direction was more likely than before, but it wasn’t 100% determined by axiomatic legitimacy. Every culture starts with certain presumptions. In Chinese culture, due to history and autocratic rule, there’s a presumption that whatever the government does is legitimate and beneficial to individual welfare.

This view was present in both the 1980s and 1990s. The difference lies in the ability to question and debate these presumptions in the 1980s. Sometimes, you might end up with the same view you started with, which is fine. However, the opportunity for discussion and inquiry existed.

In contrast, without freedom of discussion or what Amartya Sen called “discussion democracy,” people tend to maintain their initial views without examination.

This is evident today, where many young Chinese people, even those living in the West, refuse to engage in different mental processes and cling to their axiomatic views.

Jordan Schneider: The real question is whether a discussion democracy can exist under CCP rule. Is it possible to have a system where people like young Yasheng Huang can question the legitimacy of Beijing’s rule? Can a governing body be comfortable with this level of questioning, or was the 1980s an anomaly due to the aftermath of Mao’s era, which ended when the system responded to people asking too many questions?

Yasheng Huang: I’m of two minds on this issue. It’s debatable whether 1989 was an inevitable result of a looser autocratic system or a consequence of individual decisions by leaders and students. When I study history, I’m struck by how often individual events shape its course.

Looking at Taiwan and South Korea, both experienced massacres but didn’t reverse their economic and social progress. At some point, their leaders decided to let go and allow change.

Today, Taiwan and South Korea are vibrant democracies, arguably performing better in some aspects than Western democracies. During the pandemic, for example, people in these countries trusted their governments more readily.

Regarding China in the 1990s, it wasn’t necessarily imperative for the regime to reject all political reforms proposed by Zhao Ziyang. Hu Jintao moved China further in a statist direction, and Xi Jinping continued this trend. I attribute much of the blame to the leadership that came to power in China after 1989, whom I refer to as the “Shanghainese” due to their origins and viewpoints.

This new leadership focused on globalization, privatization, and urban development while neglecting rural areas. They viewed the countryside as a burden, believing peasants couldn’t contribute significantly to GDP growth or technological development. This perspective shaped the “China model” of urban development, high-tech industries, and infrastructure that we see today. The rural reformers, including Zhao Ziyang, were sidelined or marginalized in the aftermath of Tiananmen.

Ilari Mäkelä: I’d like to challenge your earlier statement that 1989 wasn’t that important. It seems it could be the most crucial event. The conservative old guard wanted to maintain their way, while Deng Xiaoping aligned with liberal reformers like Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. The Tiananmen Square protests allowed the conservative faction to drive a wedge between the political and economic liberals and Deng Xiaoping, who appeared to be an economic liberal but a political conservative.

This shift resulted in everything you described, but it also led to another significant change. You mentioned the ideologically stubborn youth in China today. Some argue this is also a post-Tiananmen symptom. The government decided to emphasize ideological training over economic focus. New curricula were introduced, emphasizing national humiliation. Wang Zheng’s 汪铮 book, Never Forget National Humiliation, discusses how this phrase became a classroom mantra for Chinese children.

The narrative of Chinese humiliation and rejuvenation under the Communist Party became a way to prevent another Tiananmen Square incident. By teaching children about the horrible past and the great present, while instilling suspicion of foreign influence, the government shaped a new generation. The Xi Jinping era seems to be a natural progression of two trends — nationalism in textbooks and the lack of political pluralism in the CCP.

Yasheng Huang: I apologize if I wasn’t clear earlier. I absolutely believe that 1989 was extremely important. In fact, I think it was more significant than many scholars have acknowledged. They usually recognize its political impact but overlook its economic consequences. In my revised 2008 book, I presented statistics demonstrating that Tiananmen also had substantial economic effects.

The question is whether it had to turn out this way. There’s an unconfirmed rumor among Chinese intellectuals that Deng Xiaoping considered inviting Zhao Ziyang back at one point. If true, and if Zhao had returned, would China have taken such a divergent path? My observation is that while there was a 90% chance of China ending up this way, there might have been a 10% chance that leaders weren’t as constrained by 1989 and could have continued reforms.

Taiwan and South Korea, for instance, had their own massacres but managed to move on. Perhaps some distance from the event is necessary. However, China remains stuck in a Tiananmen mindset long after the event, which I believe is largely, but not entirely, determined by Tiananmen.

Jordan Schneider: The key issue, relating to your lifespan argument, is that reform in Taiwan and South Korea occurred after the death of their autocratic leaders. China’s problem was that it had more people with charismatic, revolutionary legitimacy who lived exceptionally long lives. If Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun hadn’t been around in the late 1980s, the slightly younger generation, more open to different political perspectives, might have had more power. My counterfactual is that if Tiananmen had happened in 1994 or when these older leaders were more incapacitated or absent, the balance of power within the system might have been different. Even after Mao’s death, there were still enough people with strong beliefs in the old system and charismatic credibility to maintain their influence, preventing the new generation from asserting themselves.

Yasheng Huang: I agree with your analysis about the overlapping generations, which was absent in Taiwan and South Korea. Interestingly, the Cultural Revolution profoundly affected many revolutionary elders. While many were staunch conservatives, a few were quite liberal – more so than the technocrats who came to power in the 1990s. They were willing to think about issues systemically, which is how I define liberalism: considering solutions at a system level rather than focusing solely on leadership changes.

Take Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋, Xi Jinping’s father, for example. He was liberal not just in supporting liberalization but in making procedural arguments. At the Politburo meeting that ousted Hu Yaobang, he argued that the process violated agreed-upon rules. This was a revolutionary way of thinking in such a system, more profound than simply advocating for a market economy or democracy. His insistence on process and rules was more revolutionary than economic liberalization, although ultimately, he was defeated.

The lesson China should have learned from the Cultural Revolution was that it wasn’t just Mao’s mistakes, but the system that allowed him to make those mistakes.

Earlier Chinese Communist Party documents reflecting on that period showed this understanding. They instituted some separation of powers, with the presidency and party secretary general held by different individuals. However, this lesson was forgotten after 1989 when Jiang Zemin was brought to Beijing. Worried about his weakness, they abolished other power centers to consolidate his authority, leading to the China we see today.

Jordan Schneider: Professor, I searched for your name in Chinese and found many English language interviews about your book, but only one in Chinese. Have you considered starting your own YouTube channel or podcast series?

Yasheng Huang: I’m not very good at that, to be honest. It’s worth noting that before Xi Jinping, and even during his first term, I did many interviews with Chinese media outlets. I could go into great detail about data and evidence, much more so than with Western media. I was very impressed with the quality of Chinese financial journalism. However, the situation has changed now, not because the quality has declined, but because the political environment has shifted.

Ilari Mäkelä: Let’s examine China today then. In some ways, Xi Jinping seems to be a natural progression of these trends…

In part 3 we discuss the rise of Xi, succession dynamics, and prospects for liberalization in China’s future

We discuss…

The Steelman case for why China needed a leader like Xi Jinping,

What sets Xi apart from his predecessors,

Succession challenges in authoritarian states and likely scenarios post-Xi,

Why engagement with China failed to produce political liberalization,

How the US could have better leveraged economic relations with China,

Creative approaches to human rights advocacy in China.