India-China-US Relations in an Era of Strategic Competition

Was China destined to fumble their relationship with India?

India’s elections are underway! What does the future hold for the world’s largest democracy? Will the election results impact India-China relations? What about India-US relations?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Dr. Raja Mohan, Director of the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.

Co-hosting today is James Crabtree, author of The Billionaire Raj.

We get into:

What the border disputes between China and India can tell us about the political economy of the two nations;

The anti-imperial history that frames India-China relations;

Modi’s election prospects and India’s spirit of democracy;

What score Biden’s diplomatic team has earned in Southeast Asia;

Criticisms of Modi and accusations of democratic backsliding;

Opportunities for friction in the US-India relationship, including Trump tariffs, immigration, and Russia;

Whether the US is making a “bad bet” on India, and how India is prepared to involve itself during an invasion of Taiwan.

Harassment in the Himalayas

Jordan Schneider: Raja, can you start by explaining the history of India-China relations?

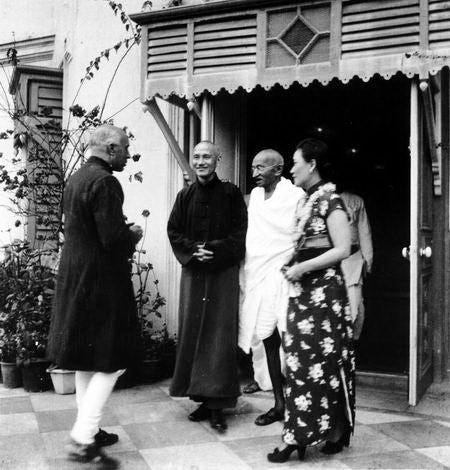

Raja Mohan: We can start our discussion of the modern relationship about 100 years ago at the Anti-imperialist Congress in Brussels. When the National Movement of India and the Chinese nationalists came to Brussels, they had this great dream about working together to overthrow imperialism and build a new post-imperial Asia.

But the story of the last 100 years is – that dream has proved to be elusive. They've never been able to work together consistently against the West, though that is the declared policy.

When the US had good relations with China, India did not have good relations with China. When China and India had good relations, they didn’t have good relations with the US. The dream of building Asian unity against the West was just a dream, because the internal conflicts within Asia are deep, including territorial conflicts and a whole range of others.

Even when they were fighting imperialism – the Chinese were fighting the Japanese, and the Indians were fighting the Brits – they still couldn’t even agree. China wanted India to work with them against the Japanese, while India said, “No, let's fight the British first.”

It was never easy to build that unity. The dream of coming together, but the inability to do so for a variety of reasons is really the story of India and China in their attempt to build modern international relations.

Jordan Schneider: I'm a little disappointed that the story doesn’t start with Xuanzang and the spread of Buddhism across the Himalayas, but we'll make do. What about relations in the 21st century?

Raja Mohan: At the beginning of the 21st century, India and China were largely on the same page trying to build the so-called “multipolar world.” The Russians had persuaded both of them to join this effort against the United States’ domination. But yet, within a decade, we saw the tensions between India and China begin to grow.

As China became stronger, the border dispute became a bigger issue. We had a series of military crises in 2013, 2014, 2017, and 2020. The last two crises were quite decisive in convincing India that this notion that we can work together with China to build a multipolar world was not going to be possible and that India had to come to terms with the Chinese power.

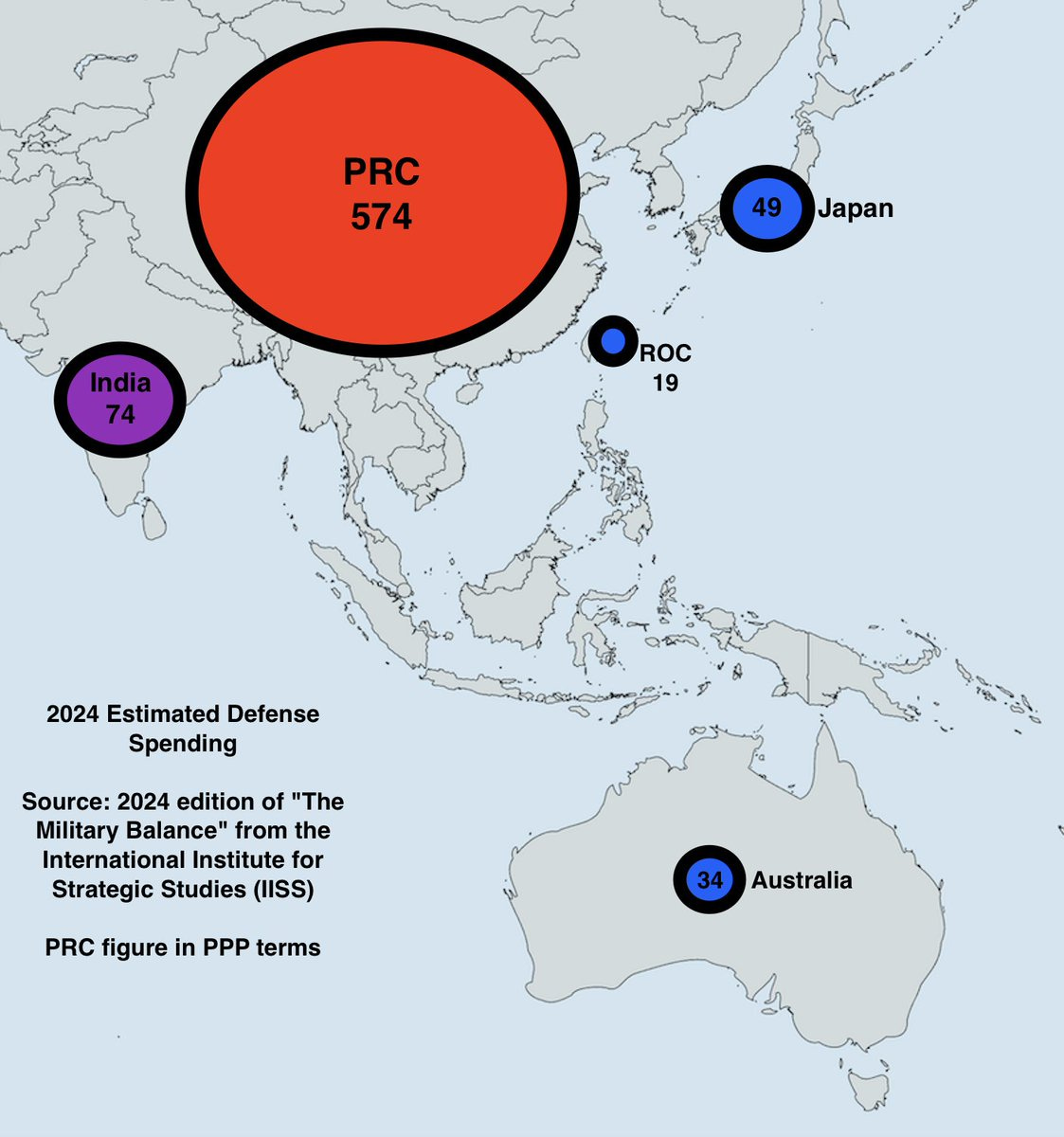

The fact is that in the middle of the 2010s, China’s GDP was almost five times bigger than India’s. Chinese military spending is four times bigger than India’s. To bridge that power gap, which is now staring India in the face, there was no choice other than working with the US and its Asian allies. That meant revising a worldview that was predicated on building a post-Western order. We had to work with the West to deal with Chinese power in Asia.

The 21st century began with the notion of building a multipolar world – a code for bringing down American hegemony – but then evolved to building a multipolar Asia with the goal of balancing Chinese dominance over Asia.

James Crabtree: Samir Saran once said, “The Chinese want a multipolar world, but a unipolar Asia,” whereas India wants the opposite.

Do you think that sums up their different worldviews?

Raja Mohan: You have to see through the oriental dissimulation. The fact is we have 60,000 troops locked up at 17,000ft against the Chinese troops. We are almost face to face. Whatever the way we speak about the distribution of power, the fact is it is Chinese power that keeps squeezing India, whether it's on the border, in the subcontinent, or in the Indian Ocean.

America is a distant power, as the Chinese classical strategist might say. You balance the near with the help of the far. Deng Xiaoping hedged Russian power by getting closer to the United States. Today, what Mr. Modi is doing is exactly the same – reaching out to the US to balance China.

We are in a Dengist moment in India. The parallel extends to India's growth, and India's opportunity to work with American capital to build itself up. Across the board, I would say, it is an era of partnership with the US. The fact is the differences between India and China are huge and the disputes have become bigger. They’ve become increasingly difficult to manage.

James Crabtree: You and I attended a think tank workshop in Singapore not too long ago where the IISS brought together a series of Indian scholars and Chinese scholars to talk about what the problems were between them. If I were to sum up the gist of that, it was that the Chinese side said, “Okay, we have this problem on the border, but maybe we can put this to one side and things will be alright. We'll work on some other things. We don't really have that much of a problem here. Let's not get it out of proportion.”

The Indian side said, “We absolutely do have a really massive problem here and you're not listening to us.” Do you think the two sides are talking past each other at the moment?

Raja Mohan: No, they’re not talking past each other – rather, their positions are fundamentally in opposition to each other. As you rightly said, the Chinese are saying, “Look, yeah, we broke 30 years of agreements. Don’t take it too seriously. There’s a new reality. Let’s keep that border issue aside. Let us get back to trade. Why are you stopping Chinese investments? Why are you stopping us? Why are you rejecting our 5G expansion and emerging tech cooperation?”

India is saying, “No, we're not going to do that.” Is there a way of breaking out of this? Maybe — if they approach Prime Minister Modi after the election and seek a reset in relations.

Because by grabbing a little bit of land, the Chinese have virtually pushed India to the American side. It has pushed India to focus on self-reliance. India is now focused on strengthening its defense and other capabilities. In many ways, what Xi Jinping has really done is shaken India out of its rhetorical, anti-Western posturing. India has largely been cured of it. But it will be open for a deal in which the pressure on India on the borders can be reduced, but I don't see them being able to return to a happy partnership like before.

Now, there is expansive competition in the Indian Ocean, in South Asia, and in global forums. I don't see how that can be wished away, but they can come to some kind of a modus vivendi on the border. I suppose the Chinese have an opportunity next year. But so far, there's no evidence that they want to fundamentally recast their position towards India.

Jordan Schneider: I think we need a little more history. Nehru and Mao were on the same side of the global non-aligned movement, but there were border disputes back then too.

Where were the forks in the road that led us to this point today?

Raja Mohan: We already discussed that we couldn’t find common ground in the interwar period. After independence, we thought we could put that behind us to cooperate.

That couldn't be done because of Tibet. Their relationship to Tibet has always been in dispute. Nehru thought he could put the border dispute aside and build a relationship by recognizing China when much of the Western world was isolating it. That attempt broke down in the late 1950s and the early 1960s. Then, we had a 30-year chill in the relationship.

At the end of the Cold War, we started all over again. The Russians convinced us, “Look, America is a big, bad, evil, unipolar power. Let's all get together to reduce the dangers of a unipolar movement.” India thought it was a good idea even as it began to engage the United States. This was the moment when India and China had some kind of peace on the border, the relationship was expanding, and trade was expanding.

That broke down, I would say, 10 years ago. Chinese power with respect to India had grown so much that the Chinese believed they could dictate the terms of the boundary settlement.

It’s the same approach China has taken with their neighbors in the South China Sea, and with Japan. In every fight they have picked, the Chinese have calculated, “There can be no countervailing coalition. We can always deal with the Americans on a bilateral basis and the US will not be able to put together a countervailing coalition.”

India surprised them by moving closer to the US and being willing to join the countervailing coalition in Asia. What we've seen in the last year is that more and more countries are willing to join this coalition, because the Chinese were unwilling to show any generosity or goodwill to its neighbors, despite all the CCP’s talk about a community of common destiny (人类命运共同体).

The assumptions that their neighbors were too weak to come together and that America was in decline both turned out to be wrong.

Jordan Schneider: Xi’s decision to pursue these border disputes has always surprised me. Of course, I come from a country that hasn't had a border dispute in more than 100 years.

But the idea that a few kilometers in the Himalayas could be more important than a functional economic and diplomatic relationship with India, makes me feel as though there's something deep and psychological going on with Chinese decision-makers that I do not really understand.

Why do you think border issues still have so much salience today?

Raja Mohan: At least in Asia, we are newly independent countries. We attach great value to territorial nationalism. The idea that this is our country, it belongs to us, and therefore we are willing to fight for it, is a common sentiment all across Asia, whether it's China, India, even Japan, or Korea. The number of territorial disputes in Asia is enormous.

When we talk to the Chinese, they say, “Look, this was our land. We’re just taking what is ours.” Indians would say, “Sorry, it's not.”

Deng was always wise, and said, “Look, leave it to the next generation. Don't quarrel over this. Let's focus on development.”

Xi has abandoned that line. A lot of people think Chinese stand 10 feet tall, they look far, they're wise. The fact that they picked a quarrel with all their neighbors, at the same time, says something about the level of miscalculation that has gone on in China. I'm sure professionals in Chinese diplomacy can see that. One doesn't know when a correction will come, but at some point, the correction will come. At that point, I think there will be room for a reset between China and its neighbors.

James Crabtree: The crux of this issue is that a Western coalition without India looks way more flimsy. When you think that China has made a strategic miscalculation, it might be that it was just a mistake, but it might be that you just don’t understand the incentive system within the CCP and the military hierarchy.

Raja explained that China made a rational calculation, which is that it felt if it threw its weight around on the border, India wouldn’t have many options. It turned out India actually did have some options. It just had to junk many decades’ worth of ideological baggage, which it has done with great speed.

There’s another account of what happened, which was that it was an accident. As the Chinese on the border got involved with an emergent set of behaviors, which got out of control, the Chinese got backed into a corner and didn’t feel they could back down against the weaker party.

Which of these do you believe is true? Was it deliberate and driven from the top? Or was this a case of local commanders going too far, but feeling like they couldn’t back down?

Raja Mohan: Both were true. For almost 30 years, starting from the late 1980s and early 1990s, we didn’t settle the boundary dispute, but we established a set of rules to manage peace and tranquility on the border.

One of the main agreements was not to move large numbers of troops close to the border and to inform the other side if you plan to do any kind of military exercise. That gave the border a sense of stability.

What happened in the summer of 2020 was the Chinese suddenly moved a large number of troops close to the Indian border. That was a surprise for India. India had to respond, and deployed its own troops because China had just broken three decades of agreements.

Stuff happens when you put so many troops together. In Galwan Valley, a number of Indian soldiers and some Chinese soldiers died in a physical clash. That exacerbated the situation. These were the first deaths on that border in nearly 50 years. The death of the Indian soldiers then made it harder to walk back for either side.

The accident does not take away from the fact that – what China has been doing on our border, basically salami slicing, pushing closer, edging on the dance on the border with your military, thanks to the modernization of infrastructure in Tibet, this is exactly what they've been doing in the South China Sea.

Jordan Schneider: Also, that was four years ago now. If China wanted to give olive branches, there were plenty of opportunities. What you've seen over the past few years – correct me if I'm wrong – is just more buildup, more new roads, more new bases. There has been no explicit or tacit sentiment that China wants to put this behind them in favor of selling more Huawei products in India.

Raja Mohan: We had almost 21 rounds of military talks. But the fact is the bulk of the deployments made in 2020 are still there, and there's been no movement.

Meanwhile, the modernization of Chinese infrastructure in Tibet and the Indian response to it has meant this disputed border is now also militarized. Before, neither side had massive infrastructure on the Indo-Tibetan border. That has changed because the PLA modernized the infrastructure in Tibet, and once they did it, India had to follow suit.

If you're negotiating, the pressure to establish claims has also grown. Therefore, I think we're in the worst possible situation.

Much of the focus has been on eastern Ladakh in the northwestern part of the border that is between our Kashmir state and Tibet. But we're almost in a semi-permanent military confrontation all along the 4,000 kilometers of frontier between India and China.

At some point, both sides will have to say, “Look, is this good for us?”

As the Chinese proverb goes, “He who tied the knot must untie it (解铃还需系铃人).” India is waiting for the Chinese to start untying it.

James Crabtree: I saw the Indian ambassador when I was in Beijing last week, and I had a chat with him about how things were going. There didn’t appear to be anything moving in the relationship. Then, within the last week, Prime Minister Modi made a statement saying, “Relations should be improved in one form or another.”

Was this a pre-election signal or did it relate to something that was going on the border?

Raja Mohan: James, you and I have been newspaper journalists and editors. The headline creates an impression that is not necessarily true. The headlines said, “Oh, my God, there's a change in Indian position.”

I don't think Mr. Modi was signaling a change in position. Mr. Modi said, “Look, we like you. We want a good relationship. Why don't you fix the border?” They were creating the space for a reset.

There was a brief attempt at this BRICS meeting in South Africa last year. The two leaders were present, there were intense negotiations actually going on at the border. It looked like some deal could be done. In the end, it didn't work out. My sense is that post-election, there could be a moment to take a fresh political look at the crisis in bilateral relations.

Domestic Politics and Modi’s Third Term

James Crabtree: How's Modi doing and what should people be expecting in the elections?

Raja Mohan: If you go by the opinion polls, it looks like he's winning by a reasonably big margin. Last time, the BJP got about 303 seats in the lower house of parliament out of a total of 540 (India has a Westminster system). There might be some increase, but the opposition parties led by Congress are hopeful they can bring down the BJP by a couple of notches at least, if not deny them a majority. There is a contest, but I think it is a one-sided contest at this point.

The problem for many voters is that there is not a credible alternative to Modi. If there was one, perhaps you could have said there could have been a better challenge. We'll see him coming back strongly.

Mr. Modi is so self-confident that he says “my third term” before the elections. He's also saying, “Businessmen, parliamentarians, look, what you've seen so far in the last 10 years is just a trailer. The real movie will begin now. We're going to do big things. We’re going to do bold things. There's going to be more reform. There's going to be more transformational change in India.” In a sense, he is generating much greater expectations for some decisive action in the first 100 days of the third term.

Even before the elections are completed, the wooing of the Western capital has not stopped. Mr. Musk is arriving in Delhi this month and is expected to close a deal that involves a major investment in producing Tesla EVs in India. He's also meeting a large number of Indian space startups because India has done some privatization in the last two years under Modi. In the two sectors where Musk is a dominant force, space and EVs, Modi's opened up room for collaboration. My sense is that they’re going to see a lot of action there.

Similarly, on the high-tech stuff, I'll just add one more point, the semiconductor mission which was started in India, nothing happens in a hurry. The fact is, since Mr. Modi's visit to Washington in June last year, that's 2023, the determination with which he has pursued the semiconductor mission. Now, we have at least three major projects on the semiconductor side which have been launched in the last few weeks. Things are moving, especially in the high-tech sector where the connection between India and the US capital is getting stronger by the day.

James Crabtree: I thought it was interesting that you said India is now in a Dengist moment. Ruchir Sharma, the investor and author also wrote a column for FT, where he argued that India is becoming more East Asian in the sense that they now have more autocratic leadership, but they are also more successful economically and in terms of manufacturing and technology.

Is that what you think we can expect after the election? Is India gradually moving, dare one say, in a slightly more Chinese direction?

Raja Mohan: Yes and no. The yes part is this — post-independence, what India did was something completely different from what Northeast Asia did, what Southeast Asia did. Northeast Asia focused on building domestic capital, gaining access to the American market, being a strategic partner for the US, and building itself up. That is what the Japanese and the Koreans did.

The Southeast Asians opened themselves to foreign capital, gained access to Western markets, and brought in Western capital to produce cheap goods. Export-led growth saw them prosper. For 65 years, what India did was something in between, which is — we kept our domestic capital down in the name of socialism and we kept the foreign capital out, saying, “We don’t need imperialist money within India.” The worst possible outcome was the building up of a bureaucratic, semi-capitalist, semi-socialist state, which was disastrous for India.

Mr. Modi is really the first prime minister who is explicitly pro-capital. He's saying that, “Look, it is capital that creates jobs. We need more jobs. We need a bigger economy. Therefore, I'm going to let the animal spirits of Indian capitalism unfold.” Unlike Indira Gandhi who said, “Look, we don't need foreign capital,” in the name of self-reliance, Mr. Modi is saying, “I want more production in India. Western capital is welcome. Come and produce in India and produce for the world.”

It's more open to the Western capital in a way that we were not before. It's also open to domestic capital. The fact is that Indian capital is thriving for the first time in the last 75 years. That is the direction. In a way strengthening domestic capital, in that sense, we are close to East Asia.

As far as the East Asian authoritarian model, I would say India is too big, too diverse, and too fundamentally constituted by the number of religions, castes, and communities. There are at least 25 languages in India.

We are democratic by structure, not by upholding some kind of liberal, a priori principle, because there's no other way of ruling India.

Even Mr. Modi had to reach out to a large number of lower-caste groups, because originally, the BJP was an upper-caste Hindu party.

There is a transformation going on. The very logic of staying in power and getting at least 40% of the vote would depend on building wider coalitions. I don't think that fundamental proposition has disappeared. While you can say, “Look, there is abuse of state power. There is domination by the current government,” I don't think the domination is systemic. My sense is that Indian diversity will continue to keep us democratic.

The Trump Factor and Opportunities for Friction

Jordan Schneider: Do you predict deeper relations between India and the West regardless of who wins the US election?

Raja Mohan: That’s an interesting question, because with the US, what we've seen happen over the last 20 years, the trajectory has been up and up irrespective of the administrations in Washington and within India. Even before Mr. Modi, there has been a movement to build a new relationship with the US, there is a strong consensus on both sides. My sense is that it will continue.

India was part of the sanctions regime because of nuclear proliferation-related issues. Once George W. Bush broke out of it, conditions were created for reviving India-US technological collaboration. We see that now unfolding under the so-called initiative for critical and emerging technologies.

When India shed its philosophy of keeping the West out of the Indian Ocean, that opened space for the Indian Navy to work with the US Navy, European navies, the Japanese, and Australians. Today, India has almost 21 ships in the Horn of Africa and the Gulf of the Arabian Sea today actually undertaking a maritime security role.

The range of collaborations is expanding, irrespective of which administration is in power in Washington. My sense is this trajectory will continue to grow in the areas of trade, technological collaboration, as well as defense and strategic collaboration.

If Trump comes, there will be the issue of managing tariffs. If India is smart, it will prepare for that eventuality and say, “Look, we’ve got to find a way of dealing with Trump’s promise of a 10% tariff across the board.” India needs to show it's a little more trade-friendly.

We've not been user-friendly when it comes to trade agreements. If we want our trade with the US to grow, we have to start to rethink, because India-US trade is the largest today. It's over $200 billion, the biggest trade relationship that we have, and our government will move on.

Another issue is immigration. There are five million Indians today in the US. Will Trump crack down on them? My own sense is that any immigration policy reform in the US would still involve bringing technical talent. That's where Indian advantage is. My sense is that this issue too can be managed.

Then on the Russia question, I think it is a problem. If things get worse in the next few years, how do we reconcile our differences in Russia will be an issue. Then, as I keep telling my European and American friends, India is less of a problem in Ukraine than the Republican Party is.

What happens in the US, what happens in Europe with the Germans is far more consequential, because India is not so attached to Russia that it would squander its expanding relationship with the US and Europe. The question for India is, how do I manage the path dependence, if you will, of the legacy weapons that created dependence on Russia?

Already, you see India's not buying too many weapons from Russia, new weapon systems. It is also trying to produce a lot more spares within India. The whole focus on getting Western capital to produce weapons in India, we're starting to see some progress. I would say the Russian factor is beginning to decline in India's overall international relationship.

India sees China as a problem and Russia as a friend. For Europe, China is a friend but Russia is a problem. The Republicans and Democrats seem to have the same issue. Where do you focus?

James Crabtree: As the European in the room, I should point out that actually India’s largest trading partner is no longer the United States. It is now the European Union and has been for two years.

The most-read article about India in the West last year anyway was Ashley Tellis’ piece in Foreign Affairs, America's Bad Bet on India. He argued that for a long time, the United States had a policy of “strategic altruism” towards India, where anything that was good for India was good for the United States. In this piece, he was saying, “Nope, not anymore— don’t expect India to come and help with Taiwan.”

You can see a number of other potential pain points in the relationship. You mentioned Russia. We haven’t talked about India’s alleged assassination of Sikh separatists in Canada. You can also look at what people call democratic backsliding domestically, namely what the data suggests is an erosion of some of India’s democratic institutions and its treatment of minorities under the current government.

If you put all that together, is there a case to say that the foundation of the India-US relationship has a few more cracks in it than maybe we might think?

Raja Mohan: What's happened in the last 20 years is the two bureaucracies have moved forward with collaboration. As the Americans might say, “The train has left the station.” This notion that you can simply halt it because India won't work with you on Taiwan or India's democratic backsliding, I don't think that works politically.

If there is a war between China and Taiwan, it’s not a certainty that everyone is going to simply rally to the cause of Taiwan. Most countries are divided. This notion that India is somehow the problem on Taiwan is fundamentally wrong.

Second, I don't think the US is expecting India to sail its ships into the Taiwan Strait when the confrontation comes. My sense is what we are looking at is some burden sharing in which India can take more responsibilities in the eastern Indian Ocean to facilitate US concentration on the Taiwan Strait.

India can help without having to put boots on the ground or ships on the water. We are looking at practical ways in which we can cooperate.

There is a new realization in Delhi that a Taiwan contingency is also an Indian contingency — because if Taiwan goes under, the Himalayas are the next. That is the biggest dispute that China has. Therefore, we’re no longer seeing Taiwan as a distant conflict because the outcome in Taiwan matters to us. Therefore, it's not as if India is going to simply be a bystander.

With all respect to my friends in the US — I follow US history and US foreign policy. This notion that the US only supports democracies is shocking to me. The US could do business with China for 40 years. I don't see why they won't do business with Modi’s India. They loved the Pakistani military for 70 years during the Cold War.

The history of US policy is about pragmatism. We've seen that in the case of Saudi Arabia, in the case of MBS, how the US had to deal with it. I'm not really worried that the democracy argument is a deal breaker between India and the US. In any case, I’m a liberal. We'll have to fight those battles at home. A bunch of Americans saying, “We will not do business with India,” is neither here nor there.

James Crabtree: I couldn't agree more with that. If you look at the partners in the free and open Indo-Pacific, it does include Vietnam, which is a Leninist country.

The Himalayas are obviously the principal source of conflict, but I’d like to hear some more about the Indian Ocean. China’s submarines pop up in Sri Lanka, or China will suddenly become quite friendly with countries on India's periphery, like the Maldives at the moment.

What do you think China is trying to do in the Indian Ocean and how is India responding?

Raja Mohan: Historically, we thought about China facing the Western Pacific, India facing Indian Ocean.

The rise of China as a great trading power has also helped fuse the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. China needs resources from the Middle East and from Africa. China is not going to be satisfied by remaining merely Pacific, but it wants to be a player in the Indian Ocean. Just as the Portuguese, the Spanish, the British, the French, the Americans would come to the Indian Ocean as age of capitalism dawned, why wont the second largest economy show up in the Indian Ocean?

As a large trading state, China is building a large navy. That, again, is not a shocking outcome. It’s a matter of time, they are going to be a big force in the Indian Ocean as they build more aircraft carriers. They have the first base today in Djibouti. They’re looking for facilities, dual use arrangements all across the Indian Ocean littoral.

If you're looking at a longer view, they will be here. Maybe India has about 10 years to come up with a strategy in which we can at least secure our interests. Any such strategy on the Indian Ocean would involve cooperation with the Americans, with the Quad, even as India builds up its own capabilities and shares the burden of managing the Indian Ocean dynamic, not only with the US, but with France is also a resident Indian Ocean power, which is exactly what we're doing. Which is to, after years of saying, “European imperialists stay out of Indian Ocean, American imperialists stay out of the Indian Ocean.” Today, Mr. Modi says, “You're welcome. Let's all work together for the” — what is it, the rules-based international order and a good maritime behavior in the region.

Here is a problem for India. The problem for India is that much of its defense resources go to the continental realm to defend the land frontiers against Pakistan and China. It cannot devote more than 17%, 18% of its defense budget to navy. Even though the Indian Navy is pretty large, is the fourth largest in the world, it needs to have a coalition strategy if it wants to be effective.

The naval side, as China becomes a major power, the coalition strategy becomes more and more important for India, and for the US too, are sharing this burden with India, helping India take larger responsibilities, boosting Indian capabilities on the maritime side is also helpful. That's where we are. The Quad is really about a maritime coalition. My sense is, as Chinese naval power grows, this coalition will also get deeper and deeper in terms of the things that it does.

Jordan Schneider: Okay. You mentioned the Quad. Let's do — I don't know, give Biden and multilateral diplomacy in South Asia a grade.

Raja Mohan: A-minus, at least. In 2020, nobody believed you could really bring all these guys together. The story used to be that America was in decline, and we would all be happily living under the Chinese hegemony in this part of the world. This idea that our friends in Southeast Asia, like Kishore Mahbubani was saying, “Look, the story is over. China has won and the West was too incompetent to do anything.”

The amount of time Biden administration has spent sheerly in terms of showing up to high-level engagement with the region, has been important. They have expanded cooperation with Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, the Philippines, and with Vietnam.

People were looking for an alternative. The moment the US says, “No, we're going to be around. We're going to stand up to Chinese domination,” a lot of Asian countries would take that opportunity, because that increases our leverage, our negotiating capabilities. Things have changed.

This idea of a “latticework” is popular in the Biden administration. Here again, what the US has done is to look beyond mere bilateral alliances to building partnerships with countries that are not going to be allies, like India or Indonesia. At the same time, they encourage partnerships between the allies and the partners — moving from a hub and spokes model, which was a post-war construct that US had developed in Asia, to a networked security where many of the regional powers will come together and work together to provide an architecture in which Chinese power can be balanced.

That scheme of a latticework, the scheme of building a coalition where the US actually can back countries that are willing to stand up, unlike allies in Europe. While Europeans say, “Let the Americans do everything,” today, Japan is saying, “We are willing to take on a larger burden.” India has its own great power aspirations. Therefore, it says, “Look, I'm going to contribute.”

Some countries in Asia are not passive partners on the NATO train. They're willing to do things for their own interests, not because America wants it.

Meanwhile, this notion that the West is in decline or the US is in decline, we see the date at which China might overtake the US is being postponed, probably indefinitely. The US is today coming back on the economic side.

The US has the top five tech companies. California has a GDP which is bigger than India's. The resources the US can actually deploy if there is political will is massive. We've seen some demonstration of that in the last few years.

My sense is, if the technological revolution continues to unfold, the US weight will continue to grow relative to Europe and China. That's going to make it much more interesting in the region, rather than this notion of a predictable, elegant American decline under joyful China's rise.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned tech. How did ChatGPT land in India? Are people excited or scared about our AI future?

Raja Mohan: No, I think we're loving it, as the Americans say. Indian elite was always very tech-oriented. If you go back to right from the 1940s, the idea that, look, technology was the kind of thing that was going to bind India and the US.

The first nuclear reactor in Asia was built in India by General Electric in 1956. The first satellites in Asia were built for India by Ford Aerospace.

The notion that India and the US can work together in technology is a deeply held one. The politics were never in synergy. Today, what you're seeing is really the coming together of India's large technical pool of talent and natural connections with Silicon Valley.

In fact, the difference between India and the US on AI is this — Americans say, “Danger, danger, danger. Let's limit it.” That's the Biden administration. India is saying, “No, we want to use it to accelerate India's development.”

At the Bletchley conference on AI, for example, the Western proposition was to find guardrails. While India was saying, “No, we need it more.” What we've seen happen is really some of India's enthusiasm has become infectious.

The recent visit to India by Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella highlighted the value of Indian innovation. We have 25 languages. They’re trying to use the Indian diversity to create structures that are going to be very helpful in thinking through the next stage of AI and ChatGPT development.

We're fully on board. My sense is with the semiconductor mission, with NVIDIA now promising India to hand over the chips, the special chips, we are at a very important moment. That's the goal of the critical and emerging technologies initiative between India and the US at the formal level, but it's really the huge surge of collaborations between the Indian startup ecosystem and the American Silicon Valley Capital.

Historically, American capital helped boost the Chinese tech sector. For all the talk about Chinese tech sector's growth, it was American VCs who really helped fund those whole advances.

Today, something similar is beginning to happen with India, and the old constraints on technology collaborations have gone. The logic of money and business is actually going to propel us closer to each other. In areas like semiconductors, space, and the use of digital public infrastructure, we're really coming together in a big way. I would say that it's the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

Jordan Schneider: Yeah. AI diffusion has been a big theme of ChinaTalk over the past few years, and the idea that developed countries will be too scared to take the plunge while the developing ones see more upside and ultimately, gain more from these technologies or something definitely will be following in the years to come.

Recommended Reading

Jordan Schneider: Let's close with some book recommendations. What do you think ChinaTalk listeners should be reading to upgrade their understanding of India?

James Crabtree: There's my book about the rise of billionaire capitalists in India. Also, there's a book called The New India by a journalist called Rahul Bhatia. I'm very confident this is going to be the big India book of the year. It brings together the story of the rise in big tech in India and the rise of the BJP.

He's a fantastic author and essayist, one of the most talented longform writers in India. That one will be really worth reading.

Raja Mohan: The Western liberal focus on one set of developments India is blinding them to the larger social churn that is going on within India. I would say, to understand the rise of the BJP, there is a very good book that has come. It's called The New BJP by Dr. Nalin Mehta. He was also a former colleague at the National University of Singapore.

There's a lot of data there to show how the BJP expanded its social base, how did it bring a large number of castes, which were not traditionally supportive of the BJP into its pool. How has the representation of the lower caste changed in the elected representatives in BJP-dominated states and in the positions of the party hierarchy?

Some say the BJP is the world's largest party, not excluding Chinese Communist Party, and it is really well-organized. This book, The New BJP, does give some insights into the social side of the broader internal coalition that the BJP has built.

James Crabtree: Jordan, if you want to chuck a couple more in, given this is a India-China discussion, then there are two books that jump to mind on that. One is by Tanvi Madan at the Brookings Institution. She wrote a book called the Fateful Triangle, looking at the history of India, China and the US over the second half of the 20th century.

When I was in the Indian Embassy in Beijing last week, I was looking on the pictures of all of the previous ambassadors, a real array of Indian diplomatic talent who sent to Beijing. They really do send their very best to Beijing. It's the most important bilateral relationship, I would say.

One of them is a guy called Vijay Gokhale, and he has written three books recently on the India-China. One of them is called The Long Game, which is how the Chinese negotiate with India. All three of Vijay Gokhale’s books either on the Indian view of China or the Chinese view of India, they’re all good. Those would be some good books, if people are interested on the interaction of India and China.

Raja Mohan: The Long Game is certainly a good one in a way — It tells you the question, Jordan, you were asking earlier, why have we not been able to solve the problem? It tells you the difference in the negotiating strategies and assumptions which led to the real crisis today, deep structural crisis in the relationship.

Jordan Schneider: I'll just throw one in here. Actually, in college, I took one course on India. The India book that really started stuck with me, Ramachandra Guha, India After Gandhi.

The prose is excellent. Anyone who likes good history writing should pick it up.

Raja Mohan: Guha is a genuine liberal and he brings in his very strong voice. His critique of the government is widely supported. On many issues, he's been really ahead of the curve, I would say.

One such issue is his view that India should not be a major power. India not only ought not to be, it should not even try to be a great power. That also reflects a tradition within India, this self-abnegation, Gandhian tradition of saying, “We don't do this kind of stuff.” There, the story has moved on. As India's relative size in the hierarchy — as India's relative size of its economy grows and as India's position in the hierarchy of the major powers goes up, India is on its way to becoming a major power.

Just by sheer weight of its economy and the prospects for its growth will put it in a position where it has to take larger responsibilities. Unlike Japan and Germany, it's not an ally. It can't simply say, “Look, Americans, you do the hard work. We'll make the money.” In a sense, it has to play a larger role in shaping the world. How India does it, that is the big question that Guha does not address but I think his book is brilliant.

His critique, India should avoid great power aspirations was something that Sonia Gandhi and the Congress had largely approved. There is that tradition that we are not like the classical Western powers. We are different.

Under Modi at least, that argument has been defeated by the other side. India wants to be a power, and most people in the country seem to love that idea, good or bad.