Innovation Emergency with Trump 1.0's Patent Director

"Every indicator points in the same direction"

A friend and past ChinaTalk guest Walter Kerr is trying, ala Fast Grants, to step in the gap to provide funding to the most effective organizations most impacted by the USAID funding cutoff. He and some partners have launched the The Foreign Aid Bridge Fund and are looking to give out their first tranche of money Friday. I donated a few grand this week and think you should too.

Walter runs Unlock Aid, new think tank that has done some great work to make USAID a more efficient and effective organization. Have a listen to him on ChinaTalk (iTunes, Spotify, YouTube).

How do patents influence emerging technology innovation? How far could AI and DOGE push our current IP regime? Does it matter that China issues way more patents than the US does?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Andrei Iancu, director of the US Patent Office under the first Trump administration. Andrei has degrees in aerospace and mechanical engineering, and worked at the legendary Hughes Aircraft Company before going to law school. He is currently in private practice at Sullivan and Cromwell.

Co-hosting today is ChinaTalk editor and second year law student at Duke, Nicholas Welch.

Have a listen on Spotify, iTunes, or your favorite podcast app.

We get into…

The mounting evidence that China's patent system now dominates America’s, and whether these indicators constitute an emergency in the innovation ecosystem,

Why some US companies now prefer Chinese courts for patent enforcement,

The fundamental tension between private rights of inventors and public access to innovations,

What congressional inaction on patent eligibility means for AI innovation, and the bills that congress could pass to immediately jumpstart emerging tech investment,

What the current administration could do to help USPTO juice the economy,

Controversy surrounding the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), and whether DOGE could put PTAB on the chopping block,

How Trump will approach patent law and intellectual property rights, including perspectives on appointments and potential reforms.

Thanks to CSIS for partnering with us to bring you this episode, the first in a three-episode CSIS Chip Chat series.

Legislative Omissions and the Political Economy of Patents

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start off with the central contradiction in patent law. What are the two equities that this whole legal superstructure is trying to balance?

Andrei Iancu: Patent law has existed in the United States since the founding of the country. It’s in the body of the Constitution in Article I, Section 8, Clause 8. This is the only place in the entire Constitution where the word “right” is mentioned other than the Bill of Rights. They thought it was that important. The Patent Act of 1790 was the first law passed by Congress after the country was founded. Since then, it has been a central part of the United States economy.

Patents, and in fact all intellectual property rights, balance the private right of the individual creator versus the public right to access that creation. On one hand, it gives exclusive rights, as the Constitution says, to one’s inventions on the technical side, or one’s artistic creations on the copyright side. In exchange for that exclusivity, the creator makes the invention public, and the public has the right to see it and potentially use it.

This is the quid pro quo. This tension between the private right of protection versus the public’s right of access has existed from the very beginning. Thomas Jefferson was the first head of the patent system beginning in 1790. He was reviewing patents at night, and at that time, he said patents were, “an embarrassment” to the American economic system, because they are a sort of monopoly, which he hated. He was very uncomfortable with removing the public’s ability to freely access ideas. However, around the same time he also said that patents have “given a spring to innovation beyond [his] conception.” That tension in Jefferson embodies the tension that exists in the patent system to this day.

Jordan Schneider: Over the course of your career, what role has each branch of government played in balancing the rights of creators and consumers?

Andrei Iancu: Congress creates the laws, the administration enforces and administers those laws, and the judicial branch has to interpret those laws. It begins with Congress — they have to make the patent laws in the first instance, and they’ve been struggling from the very beginning.

Once the laws are passed, it’s up to the USPTO (Patent and Trademark Office) to enforce those laws and grant patents and trademarks, while the Copyright Office registers copyrights based on those laws. The problem has been that these issues are so complicated, and the tension between the two poles I’ve mentioned is so high, that Congress has left a lot of gaps. They have been incapable of legislating.

For example, the first substantive section of the patent code is Section 101. It defines which types of technologies are eligible to receive patents. It is so complicated it hasn’t been legislated on since 1793. The last time Congress wrote a law to say what technology is in and out was in the 18th century. Now, the Patent Office and the courts are trying to figure out how artificial intelligence and DNA processing fit into this 18th-century statute.

It’s a mess because Congress hasn’t returned to it in 250 years. There is a bipartisan bill to address this issue called PERA (Patent Eligibility Restoration Act). It was introduced in the Senate last year by Senators Tillis and Coons, Republican and Democrat respectively, but the bill didn’t move. We’ll see if they introduce it again. It hasn’t been touched since 1793, and it really is important that they get to it, but the issues are really hard.

“[I]f you observe a genetic mutation associated with a particular risk, such as diagnosing cancer of a particular type, and then you isolate it and create a diagnostic kit… That is the essence of invention. It takes a lot of time, money and investment to find that out…

All human invention is the manipulation of nature towards practical uses by humans on this planet. We can exclude nature itself, but any human intervention and manipulation — that is what human innovation and engineering is, and it should be eligible for a patent.”

~ Andrei Iancu making the case for PERA to the Senate Subcommittee on IP.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on the political economy of this. On one hand, you have the political economy fights over who gets to make more money — is it the generics, the healthcare system, or the biomanufacturing companies? Then you have this philosophical arc happening above all the individual industry fights. I’m curious, Andrei, as the pendulum swings, are the changes within specific industries, or is it a broader national shift over the decades where you go from the system more supporting the patent holders versus the patent users?

Andrei Iancu: Let me make something clear here. There is only one patent system in the United States, and by definition, it has to apply equally to all technologies. You cannot have patent laws for pharma that are different from patent laws for tech. Whatever the laws are, and however you interpret them, they basically have to be the same across technologies. This concept of non-discrimination across technologies is part of international agreements that the United States has been pushing for a very long time. The TRIPS agreement is a multilateral international agreement where all the member states have ratified it, and it’s fundamental to the patent system.

Jordan Schneider: Why is that?

Andrei Iancu: By definition, you don’t know where technology is going to go, and the whole point of the patent system is forward-looking. You can’t start picking winners and losers ahead of time — that’s the main reason. The other reason is one country might want to discriminate in favor of one industry, while another country might want to discriminate in favor of another industry, and it would be completely unworkable. There are other reasons too.

Nevertheless, even though the laws ultimately have to be uniformly applicable to all technologies, there are certain technologies that drive change in the system. For example, the major tension for the last couple of decades has been between big tech and pharma. This is a complete overgeneralization, but by and large, you could say that the pharma industries and life sciences industries want and need stronger intellectual property rights for a variety of reasons. Whereas big tech companies, by and large — again, I’m super generalizing here — tend to want weaker intellectual property rights.

Whoever prevails in that fight for their own corporate interests will affect everybody. That’s the interesting thing. It’s not like tech can demand changes that only apply to tech, or pharma can demand changes that only apply to pharma. Generally, this has been the tension between these big industries, and the pendulum has been swinging back and forth according to who has had more political power in the last few decades.

Nicholas Welch: Maybe we can stay on emerging tech for a moment. I’d be curious for your take on patent policy with regard to biotech. Let me know if this characterization is true, but your approach to patent law differed from your predecessor, Michelle Lee, and your successor, Kathi Vidal, in a few ways. You might be described as very supportive of patent rights, whereas Lee and Vidal could have been concerned with patent quality. Vidal made policies which caused invalidations of patents to rise from 59% in 2021 up to 71% in the first half of 2024.

In the context of emerging tech specifically, do you feel like companies have good reasons to demand patents, or should USPTO be cautious about issuing patents to technologies we don’t quite understand yet?

Andrei Iancu: Let me challenge the premise a little bit. It is true that invalidations in post-grant proceedings at the Patent Office have risen in the last administration with my successor, and I don’t doubt the numbers you cited. But that does not indicate an increase in patent quality. Those two are completely separate things.

I very much am in favor of and always spoke about the importance of issuing and maintaining correct rights, but that goes both ways. Just because you’re invalidating a patent doesn’t mean you’re increasing the quality of the patent system. The Office could be wrong in invalidating that patent, and that is a mark of lowering the quality of the system as a whole.

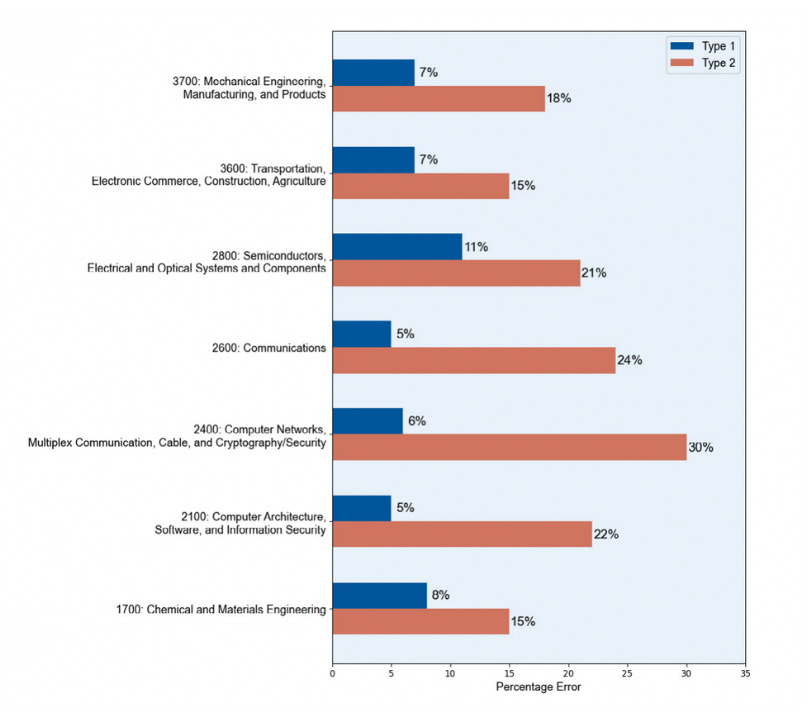

Recently, the Sunwater Institute published a report that shows the Patent Office errs significantly more in the direction of incorrectly not granting patent rights than incorrectly granting patent rights. While the incorrect grant of patent rights is a few percentage points in the single digits, incorrectly denying patent rights is in the double digits, according to the recent Sunwater Institute report, and I commend you to that study.

The question then becomes, which one is worse for the economy? You don’t want errors either way. But if you’re going to err on one side or the other, which one are you going to choose?

Right now, the Office is erring too much on the side of incorrectly withholding patent rights or incorrectly removing patent rights once they have been issued. That can do tremendous harm to innovation and investment in the United States.

In a free market economy like we have here in the United States, there are very few incentives that enable investment in risky new technologies. By definition, innovation is risky — it’s new. You don’t know if it’s going to work or not. Probably 8 out of 10 new inventions fail for one reason or another, and some of these inventions are really expensive to bring to market.

Drugs are a very good example. It costs, on average, about 2.5 billion dollars to bring a particular new drug to market by the time you do the basic science research, all the human studies, the FDA approvals, the marketing, and so on. It’s super expensive, and a lot of those ultimately fail. Now, in addition to all that, if they succeed, a lot of these innovations are easily replicable. A drug is very easy to replicate — you can just reverse engineer the chemical formula usually, and there you have it.

Because of that risk, high cost to bring it to fruition, and easy replicability if you succeed, what incentivizes the investment community and the innovation community to invest time and resources in these risky new technologies as opposed to investing in something else like the old stuff, the tried and true stuff, or opening another restaurant? In a free market economy, there’s not much incentive without the protection of a strong patent system or strong intellectual property system at large.

We risk losing the investment and innovation engine in the United States. This is a big problem with new technologies like artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and quantum computing — things that are long-term, very risky, and very expensive to bring to fruition. If we don’t maximize our innovative output and investment input into that innovation economy, we’re going to be left behind because we are in a humongous technological race with China and others.

Nicholas Welch: You mentioned in the context of drugs, they’re very easy to reverse engineer — you can just take the pill and analyze it. Semiconductors, on the other hand, are super hard to reverse engineer. When I read through Chris Miller’s Chip War, it sounds like the reason the Soviets couldn’t keep up with our chips is they’d get a chip and it would take them forever to take it apart and figure out how they made it. Once they figured out how it was made, they didn’t have the right tools to make it themselves, and by the time they got that, we were already onto the next generation of chips. Curious for your thoughts about how the patent system is valuable or not to the semiconductor industry, especially because those products are just so complicated to manufacture.

Andrei Iancu: They’re very complicated to manufacture and more difficult to reverse engineer for sure, for the reasons you’ve mentioned. However, it’s really expensive to get them going. Look what’s happening right now with the CHIPS and Science Act — we’re trying to get companies to invest to create new plants in the United States. It’s really hard to get this off the ground. It takes decades to bring one of these plants to fruition and tens of billions of dollars.

It’s one of these things where, yes, it’s more difficult to reverse engineer on the back end — it’s not impossible, but it’s more difficult. The investment risk is so high. I was a supporter of the CHIPS and Science Act because I think the United States needs to do more, and a lot more, to create these new technologies and stay competitive.

However, there was no intellectual property provision really in the CHIPS and Science Act — patents were barely mentioned. If you do not combine this financial investment that CHIPS and Science authorizes with a strong intellectual property system, it’s just not going to happen. The private sector investment will not come along at scale. Some of it will for sure, but at scale it won’t come along to co-invest with the public funds, and you cannot do it with public funds only.

Unfortunately, what I’m saying is turning out to be correct. We are investing in the CHIPS and Science Act, but it’s kind of like putting money through a sieve because it’s not going to take unless you have a robust intellectual property system. You need to strengthen the system and give guarantees to the investors that if they co-invest with the United States together with the public funds and they invest at scale and we create these plants, we will not lose the IP to China or somebody else and we’ll be able to enforce it if necessary.

Jordan Schneider: Coming back to a comment earlier, I’d be curious for your take on the amount of discretion that the Executive branch and the USPTO (US Patent Office) has in particular. How far, without new legislation or some new Supreme Court ruling, could an administration potentially push it in one direction or the other?

Andrei Iancu: The PTO director and the administration have some discretion to move that dial, but not complete discretion. The administrator is always bound by the legislation on one hand and then by the courts interpreting that legislation on the other hand. Within those parameters — what the law is and how the courts have interpreted it — there is always flexibility, and the PTO director can dial those things up.

Just as one example from the very first point we discussed earlier in the program, the PTO director certainly has the ability to institute policies at the PTO, institute examination guidelines, and train the examiners to make sure that we grant correct rights — that we don’t grant patents that should not be granted, and at the same time we don’t deny patents that should actually be granted.

On the back end, when reviewing already issued patents, the PTO director has discretion to dial how many or what types of reviews and patents we will take on and exactly what the review criteria will be, again within the bounds of the legislation and as it’s been interpreted by the courts. Just as Nicholas identified in the statistics earlier, you can see from administration to administration — the last administration, for example, canceled proportionately more patents than my administration did in the first Trump administration.

There’s definitely that bandwidth. Unfortunately, the less Congress legislates, the more discretion there is for the director. I’m not saying that’s a good thing — I don’t think it is. Patents and IP in general are long-term assets. Companies need to make investments in these assets for the long run, and not knowing how some of these rules are to be interpreted is not good for the economy.

I’ll give you just one example. There is a bill called the PREVAIL Act, which would tighten the laws surrounding post-grant reviews (PGRs) and IPRs, which we’ll talk about. These are proceedings where the office reviews whether patents should be left in force or canceled. This bill tightens the laws surrounding those proceedings. I’m a big supporter of that bill because it removes some discretion from the Patent Office and sets in law what those guidelines should be in many ways. The public will have a higher level of predictability surrounding the IP they have to deal with. To me, that would be a significant improvement, but we don’t have that right now. The director has significant discretion on those proceedings.

China’s Patent System

Since 2000 alone, Beijing has also undergone massive reforms of its IP system, including four major revisions to its patent law... China’s patent office, CNIPA, has hired tens of thousands of examiners and has expedited time-to-grant for patent applications. Specialized IP courts in China provide rapid rulings and readily issue injunctions. In fact, US companies often now sue in PRC courts when they have a choice of jurisdictions in order to obtain the injunctive relief no longer available in the United States.

~ The Hoover Institution’s 2023 “Silicon Triangle” report, pp. 178-179

Nicholas Welch: Let’s talk about China. China has their own patent administration system called the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA).

A talking point we hear all the time is that they grant a lot more patents than the USPTO does — and that’s true. The US has a test for patents based on abstractness, whereas the Chinese authority reviews the invention as a holistic whole and focuses on the technical solution. In 2023, there was a study that said more than 12,000 cases had been granted in China and Europe but denied in the United States on statutory subject matter grounds.

Should we care that China grants a lot more patents than the US, and is there anything we could learn from how China runs their patent system?

Andrei Iancu: Yes, we should care. It is a concern to me that somehow, they’ve created a patent system that seems to be more robust than ours in some respects. China continues to steal IP at extremely high rates in many different ways, but on top of that, they also have their own innovation ecosystem, and they’re maximizing it to the extent possible for their economy. One of the things they’ve done over the past couple of decades is systematically improve their patent system, and in some ways they’ve overtaken us when it comes to some of these protections.

You touched on one of them — the Chinese laws when it comes to subject matter eligibility. In other words, what technologies are subject to patent and which ones are not. Their system is more clear and more robust than ours, which, as I said at the beginning of this conversation, has not been legislated since 1793. The Chinese system, when it comes to subject matter eligibility, is new and fresh.

That absolutely has an impact, particularly for our economy. If we want to maximize innovation in the United States and maximize investment in that innovation in our free market system, we need clear laws. We need to know the rules of the road and make sure that industry believes its investment will be protected by the rule of law. Right now, on things like subject matter eligibility, the rules of the road are unclear. You’re making all these investments and you just don’t know if it will be protected down the road, if it’s in or out of the patent system, or how it will be interpreted. That uncertainty, at least on the margins, is depressing our ability to invest at scale in these risky new technologies. That puts us at a disadvantage with China.

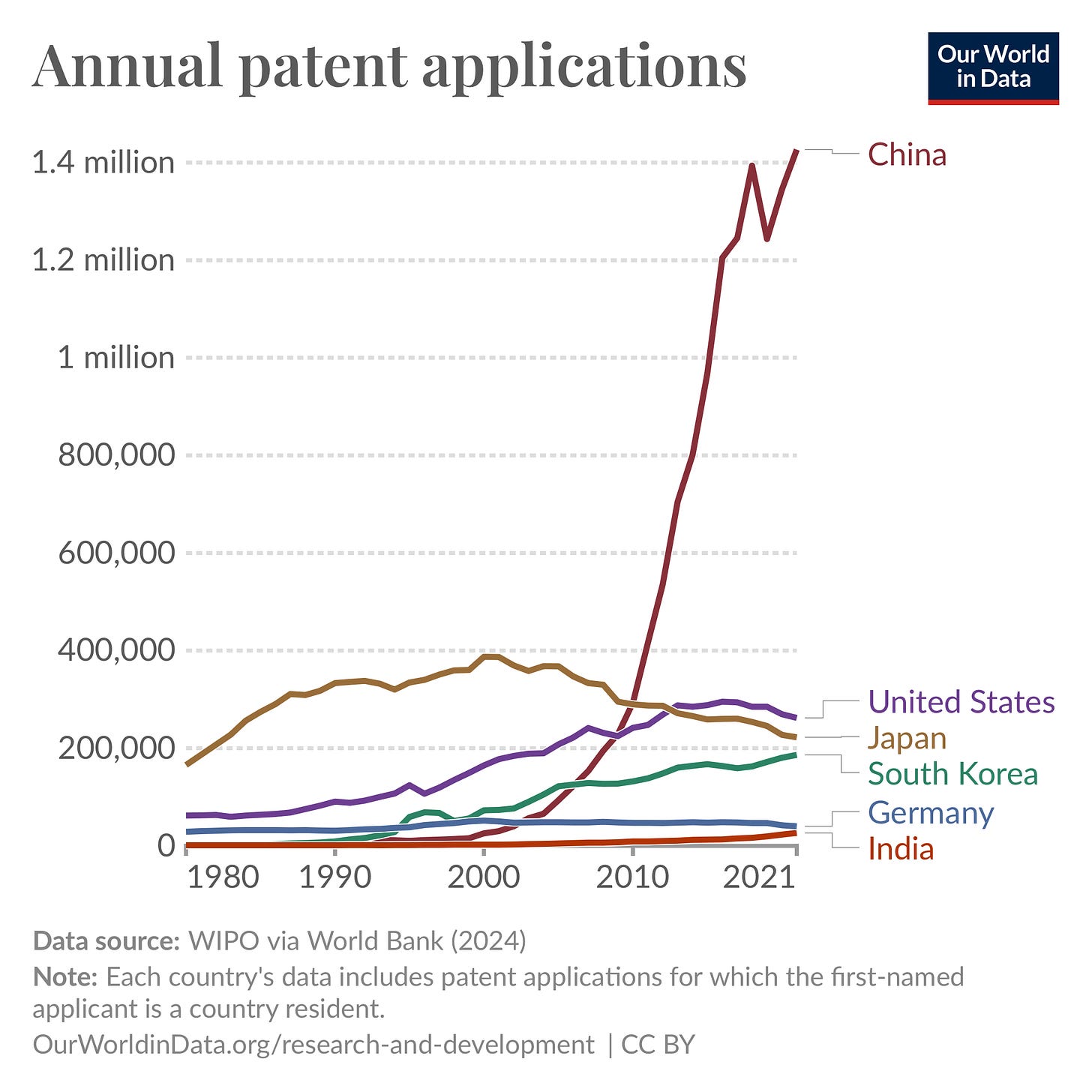

If you look at the number of patents Chinese companies have versus the United States and graph it out, it should be frightening to anyone in the United States that cares about these issues. If you start graphing 20 years ago, the Chinese were at the bottom, barely registering on the scale of patent grants worldwide, and the United States was at the top or among the top. But take that out to the present day — about 10 years or so ago, there’s a hockey stick effect that comes into play with the number of Chinese patents or patents granted to Chinese companies.

The United States is basically flat for the last 20 years — by and large, the numbers of patents to US companies are growing pretty much 2-4%, in line with GDP growth. The Chinese numbers show a hockey stick effect about a dozen years ago. It rises and then overtakes the United States about a decade ago, and now they’re blowing us out of the water. They’re blowing us out of the water across the board, but more importantly, in the technologies that really matter. For example, they’re getting six times as many patents in deep machine learning as the United States. This relative positioning applies in almost all the new areas of technology, and that should be a significant concern.

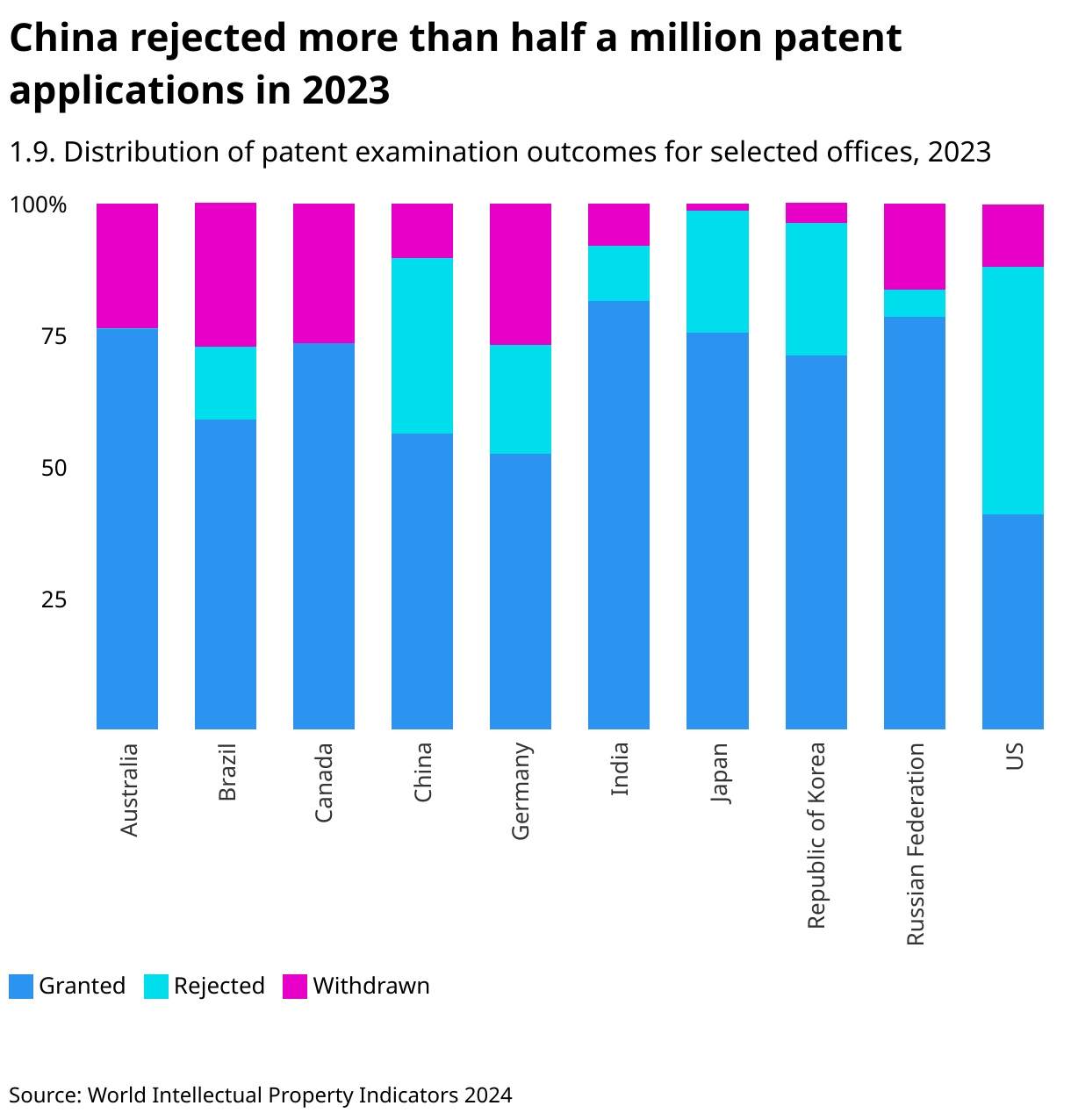

Jordan Schneider: When I see charts like that, my first mind goes to Goodhart’s law — what kinds of incentives are being set up here? It really comes down to a question of patent quality. To what extent is the amount of patents issued at the national level a good proxy for innovation? Is it better to look at the market cap of Baidu versus Meta to address that point?

Andrei Iancu: It’s a very good point. I don’t think you should just rely on the number of patents to make a definitive determination as to who’s winning the race in a particular area of technology. But it is one indicator, and it’s a really good leading indicator of where the technology will be in a little while.

Regarding patent quality — that’s the talking point that people who want to weaken the United States patent system make, which is, “Okay, they’re getting a lot more patents, but they’re weak patents, they’re bad quality patents.” I say, what’s your evidence for that? Show me the study that on average the Chinese are getting weaker patents worldwide compared to United States companies getting their patents worldwide.

I don’t think there is a reliable study out there that shows that. It’s not like all of our companies are getting the best patents in the world, either.

Jordan Schneider: With seven thousand a week, you’ll get a lot of duds too, you know.

Andrei Iancu: The Chinese are now getting three times as many patents as the United States. If you just eliminate two-thirds of those — okay, we’re even. Are there that many really terrible patents that Chinese are getting? Where’s the evidence for that?

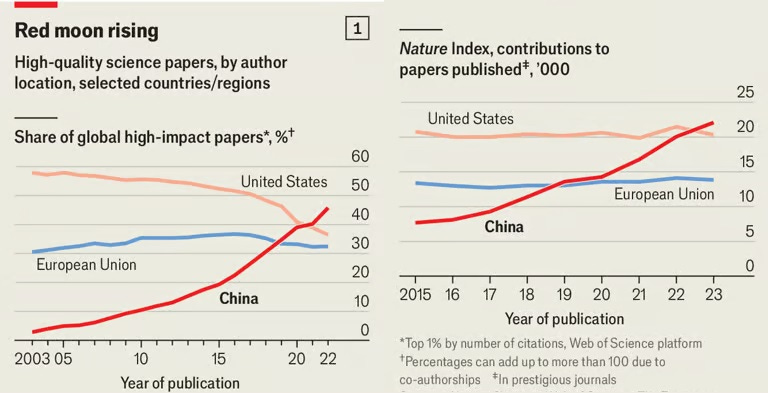

More importantly, it’s one indicator. We need to look at all the other indicators, and all the other indicators point in the same direction, with no exception. Chinese scientists and engineers are authors of more peer-reviewed scientific and technical journal articles than American authors. The Chinese are graduating many more scientists and engineers every year than the United States — not close, many more. The Chinese are beginning to take leadership roles in standard-setting committees at extremely high rates.

Every indicator points in the same direction. We can start to dismiss one or the other for one reason or another, but I don’t think the United States should lose sight and shrug its shoulders and say it’s just fiction numbers.

The evidence bears that we are in a tremendous technological race, and they are making tremendous progress.

We better attend to it right away and pull every possible policy lever to incentivize the maximum innovation output in the United States. Otherwise, we’re going to wake up in a year or two or five, and it’s going to be too late.

Nicholas Welch: Another indicator that supports what you were saying — this is from a Hoover Institution report in 2023 — PRC courts provide injunctive relief in nearly 100% of all successful patent cases. Specialized IP courts in China provide rapid rulings and readily issue injunctions. In fact, US companies often now sue in PRC courts when they have a choice of jurisdictions in order to obtain the injunctive relief no longer available in the United States. That blew me away — if American companies are choosing to sue in Chinese courts over patent infringements or to obtain injunctive relief, maybe we could start reforms and have people sue in United States jurisdictions. That’s huge.

Andrei Iancu: That is right. It’s yet another way we have weakened our intellectual property system. It is very difficult to obtain injunctions for patent infringement in the United States. If you think about what a patent is fundamentally, a patent, like any property right, is the right to exclude. If I have a house, I have the right to have a front door with a lock and exclude people if I don’t want them to come in. It’s a fundamental right of any property right. If I have a field, I have the right to put a fence around it and exclude other cows from coming to graze on my grass if I want it, or I have the right to charge people to come in and graze on the grass or do whatever I would like with my property.

Same with intellectual property. In fact, as I said at the very beginning, the Constitution says that patents and copyrights are meant to give inventors and authors their exclusive right, which means the right to exclude and the right to an injunction. But since the eBay decision from the Supreme Court about 15 years ago, that has been very difficult to obtain in the United States. Whereas in China, for example, or in Germany, it’s almost automatic, the way it used to be in the United States all along, until recently.

That basically diminishes the value of American intellectual property. It makes it less valuable and therefore less useful to inventors and investors as they contemplate what to work on and what to devote their energies to. That is very detrimental to our innovation economy. There is a bill out there, bicameral, bipartisan, called the RESTORE Act, to fix this issue. But again, it was introduced late last Congress and it hasn’t moved yet.

Nicholas Welch: In US courts, when you say it’s harder to get injunctive relief because of eBay, does that mean the alternative is just money damages? A company could say the cost of litigating and even losing would be cheaper overall — as long as a court can’t actually force me to stop using the patent, I may as well just go through the litigation. Is that what we’re referring to here when you talk about weakening patent rights?

Andrei Iancu: Yes, exactly. If you don’t have the right to exclude and all you have is the ability to charge a fee, then you are into what’s called a compulsory licensing system. That’s not really a property right.

Imagine you have your house, Nicholas. The law says in your town that you can have your house, God bless, but you can’t kick anybody out. Then along comes Jordan, and he says, “I’m setting up in your back bedroom. You can’t kick me out, but you know what? I’ll pay rent. I’m going to just live with you. I’m going to come in with my wife and my three kids and my mother-in-law and we’ll just live in your house and we’ll pay rent.”

How valuable is that house? You’re most likely going to move from that town if that’s the rule. Most likely you’re not going to buy that house or make that investment if people can come set up in your house, even if they want to pay rent. No, thank you! If I want to rent it out, I will, but you can’t force me to rent it out.

This is such a fundamental principle for real estate, real property, or personal property. Same thing with personal property — like a watch. I’m going to come and just take your watch, but I’ll give you ten bucks a month and I’ll just take your watch and wear it wherever. Who even thinks about these things? It’s laughable.

But when it comes to intellectual property rights, the American courts recently don’t have a problem saying you don’t have the right to exclude. It makes no sense, and as a result, on the margin it devalues that property right. It’s irrelevant that you can also charge rent on it. Sure, it’s helpful — it’s better than nothing, definitely better than nothing. But it is such a humongous devaluation of that exclusive right that the Constitution contemplated.

Trump and IP

Nicholas Welch: If we don’t have predictability, maybe we can get some predictions from you about the next few years coming up, because there are so many policy winds that blow toward the USPTO office. Trump, for example, has nominated David Sacks as the brand new position of AI and Crypto Czar. Sacks is presumably a “regulate AI less” kind of person. Trump’s pick for assistant AG for antitrust, Gail Slater, has been quoted saying she wants to bring back the so-called “New Madison” approach — no duty to license patents, and also that standard essential patents (SEPs) should get the same protections as other patents, which presumably stands for strengthening the rights of patent holders.

Within the leeway that we have, which seems quite large, how do you think an incoming USPTO director is going to handle some of these big issues for the next few months and years in Trump’s second term?

Andrei Iancu: To quote Yogi Berra, “It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” With that caveat, I am definitely encouraged by the IP positions in the new Trump administration. I wrote an article in Fortune magazine in October 2024 touching on many of these points, including the regulation of AI. I predicted back then that a Trump-Vance administration would be a significant improvement when it comes to intellectual property and these new technologies.

Looking at the appointments — there hasn’t been enough time to see what they will actually do — but just looking at the appointments of the individuals, I am very encouraged. I worked with Gail Slater in the first administration. I’m familiar with her positions generally, and what you just mentioned illustrates that this administration, and Gail in particular in antitrust, understands the importance of IP to a growing economy and our technological competitiveness.

The New Madison approach basically says that intellectual property is good for the economy. It’s not an antitrust issue that should be regulated from an antitrust perspective. By and large, all patents, including standard essential patents, should be treated the same way and should be given full enforcement rights. There’s no special provision anywhere in the code or legislature that standard essential patents should be treated any differently.

Back in the first Trump administration, we had a collaboration between the USPTO, the Department of Justice, and NIST to put forward policies like this. We had, for example, the 2019 Standard Essential Patent policy position that basically said what you just articulated — all patents are to be treated equally, and they have all the rights of enforcement, including injunctions, and the laws should apply equally to all patents, including standard essential patents.

The Biden administration came in, and one of the first things they did was take down the 2019 policy, so the United States right now has no policy. I am hopeful that with Gail at DOJ Antitrust and Howard Lutnick coming in at the Department of Commerce, which oversees both PTO and NIST, that we can reinstate those types of policies that are protective of American intellectual property. We’ll see how they shake out in the end, but I am very encouraged by the appointments.

Jordan Schneider: Aside from the general direction that you can reasonably project based on the appointee choices and what they’ve said so far, you have this new energy with AI plus DOGE, which wasn’t necessarily in your time in the Trump administration. How crazy could things get at PTO? What are things you would have never dared to do in your time as a director that the Trump administration 2.0, which is clearly considering pushing the envelope in many different places, could potentially do for better or worse when it comes to the Patent Office?

Andrei Iancu: Let me first say that I don’t think the PTO is first or among the first in sight for the people at DOGE. They have other fish to fry before they get to the PTO. Having said that, it’s really important to understand that the PTO is unlike almost all other government agencies.

The PTO is not quite a regulatory agency that regulates the public or taxes the public or anything else. Unlike most government agencies, the PTO creates rights. The public comes to the office and applies for certain rights — patents and trademarks — and they leave with more rights than when they came in, usually. The PTO issues over 7,000 patents every single week. A very large number of trademarks get registered every week. That is additive to the applicants and additive to the economy. We’re not the taxing authority, we’re not the regulatory authority — we help the economy.

That’s a really important distinction, combined with the fact that the PTO does not operate on taxpayer dollars. PTO operates almost exclusively on user fees, and the PTO examiners are production-based — they have to produce a certain number of units every bi-week. This is very different from most government agencies. That’s why I’m not entirely comfortable discussing action at the PTO within the concepts of DOGE, because I just don’t think it fits within that. It’s entirely possible that the new Trump administration will have some bold actions at the PTO, but I just don’t think it’s going to be within the DOGE framework, which is aimed at, by and large, reducing government and reducing government waste.

Jordan Schneider: Andrei, this sounds like you’re pleading at the pearly gates to be let in.

Andrei Iancu: I am pleading for folks to just understand that the PTO is really a special agency that, by and large, helps the economy. Now, I will say there are lots of improvements that can and should take place at the PTO.

One of the boldest things that I’ve seen people talk about in the context of DOGE is that there should be action with respect to the PTAB. The PTAB is the Patent Trial and Appeals Board. It has two functions — trials and appeals. The appeal side is the bigger side. If you’re a patent applicant and you disagree with the examiner — the examiner just will not give you a patent because somebody else invented first or whatever — then you can appeal to this PTAB. That’s the appeal side.

The trial side works on patents that have already been issued. If a patent has already been issued, somebody else in the public can challenge it and say that it’s invalid, it should have never been issued, and bring it to the PTAB for a trial. The trial side of the PTAB has been very controversial over the last decade. It was created in 2012 by the America Invents Act signed by President Obama.

It’s been really controversial from the moment it began because, by and large, it has the administration, not the independent courts, remove a granted right. That makes people uncomfortable for many different reasons, including the fact that 85% of the patents in these IPR post-grant examinations at the PTAB are already involved in a similar proceeding in court. There are now effectively two proceedings at the same time on the same sort of issues between the same parties — one in the Article III independent courts and the other one at the PTAB.

I have heard folks say, “Hey, DOGE, why don’t you take a look at the PTAB? It’s redundant government waste. You should eliminate the PTAB.” Now, I haven’t seen any serious look at that by DOGE. As I said, I think they’re very busy with other things. But if you’re asking me about one of the wildest things that could happen, I could see that happening at the PTAB. But I still think it’s far-fetched.

Nicholas Welch: Another way the USPTO is unique — the USPTO director is in the executive branch but operates kind of like a quasi-judge. They can review decisions executed by the PTAB judges who aren’t actual judges. In 2021, there was this interesting Supreme Court case, United States v. Arthrex. It was an Appointments Clause case (people should do a lot of Appointments Clause homework because that’s what tanked the Trump Florida documents case). It says that PTAB judges are principal officers, which means if you’re a principal officer instead of an inferior officer, you need to be Senate-confirmed, and they weren’t. As a sufficient remedy to this problem, we can just let the USPTO director review any decision made by the PTAB judges, because a director is a Senate-confirmed officer.

How much leeway or authority does that actually give the director? We now have this director review process for any decision the PTAB makes. The USPTO office is going to be feeling a lot of policy winds from whoever happens to be in the White House. What are the odds that some Chinese company sues a US company in US courts and it goes to the PTAB, and then Trump gets on a phone call with Xi Jinping and says, “Nice company you have there, it would be a shame if Secretary Lutnick told the patent director to not review this” or something like that? The USPTO director is kind of a judge with political valence. Am I understanding the org chart right here? What are the implications of Arthrex going forward?

Andrei Iancu: You’re understanding the org chart well — it’s a very perceptive and good question. Just to back up for a second to set the stage, the PTAB does have judges. You say they’re not real judges, but they are judges. They’re not what we call Article III judges from the Constitution, but they are administrative judges. The administration has judges in various areas. The Social Security Administration has judges to resolve disputes with your Social Security checks, the IRS has its own judges to resolve tax disputes you might have with the government, and so on.

We have these patent administrative judges — we have trademark administrative judges as well in the trademark office. They’re not independent Article III judges. The whole point of the Constitution having three independent and co-equal branches is to create a judicial branch that is independent from politics. Yes, the judges are appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate once, but that’s it — they’re lifetime appointments. The founders found that to be really important to create independence of the judiciary, to be independent of the political winds. That has worked really well for the United States for the past 200-some years, especially in disputes between private parties over private issues. You want to have this independent judiciary that deals with that so they’re not impacted by politics.

However, the America Invents Act created this new proceeding at the Patent Office, the Inter Partes Review Proceeding (IPR), where you can have private parties fight amongst themselves over private property (a patent) in the executive branch. What the Supreme Court said in the Arthrex case is that because it’s in the administrative branch, the buck has to stop with the political appointees. The administrative branch is politically controlled and it has to be controlled by the people voting in the President and therefore the President’s appointees.

The Supreme Court said that’s what the Constitution demands. You cannot have unaccountable career officials that ultimately issue final decisions from the administration that are not controlled by the politically appointed individuals. Why? Because if that were the case, the public has no control then over the actions of the administration. The people need to vote in or out based on the acts the administration takes. If you don’t have political accountability, you’re missing out on the vote of the public.

The Supreme Court said in Arthrex that the final decisions from the PTAB have to be affected or at least available for review by the politically appointed director. That was in the summer of 2021, at the beginning of the Biden administration when the Supreme Court decision came out. The PTO director in the Biden administration basically said, “That’s what the Supreme Court says, therefore I, the director, will take upon myself as a human being to review these decisions if I am asked to do that."

To be honest, I think it’s very uncomfortable to have a political appointee (who comes and goes and is subject to political pressure) call balls and strikes in private disputes between private parties. This is not a dispute between the taxpayer and the IRS — this is a dispute usually between two corporations fighting over this particular property, a patent.

For me, it’s uncomfortable to have the political appointee making those decisions. I don’t think it’s good for the public in the long run because it’s unpredictable — you don’t know who the next appointee is going to be, and patents are long-term assets. But I understand the Supreme Court point here about the Constitution — since this is an administrative action, you have to have political accountability.

It’s really hard to fit this square peg in the round hole. You’re trying to fit a judicial action — resolving private disputes between private parties over private property — but in a politically controlled administrative agency. It’s very difficult to resolve. This is why this IPR system has been controversial since its institution in 2012. People are by and large uncomfortable with a political agency resolving these disputes. At bottom, in my view, this should be left to the independent Article III courts that the founders created in 1776.

For now, we have the statute, it has to be administered, and we have the Supreme Court decision. I would personally implement that differently. I would try to create separation to the extent constitutionally allowable between the Director and these decisions for many reasons. In the end, I would try to find a way to move as much of this towards the court system as I could, because private disputes between private parties for private property should be handled by the independent courts to the extent possible.

Mood Music

Andrei couldn’t come up with a patent song so we asked Deep Research for some suggestions and it gave us these absolute gems.

The claim that all technology needs the same IP law is insane. Embarrassing if that is actually the political consensus vs just the opinion of a lawyer.

Pharma clearly has a different Tabarok Curve https://marginalrevolution.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/InnovationStrengthCurve32.png

Well written and interesting, in regards to this sentence ignores the structure of education systems: "The Chinese are graduating many more scientists and engineers every year than the United States", the structure if systems is very, very important to consider. The usa used to have a superior structure, The American Academe as we understand it was constructed after WW2 from the consolidation and centralization of the Old Republic's decentralized, diversified, and pluralistic academe, the legacy good of the old system took decades to wither away (not saying the current system is 100% bad but it mostly is and it could be far better with fairly apparent reforms), our centralization has produced grant cartels, and uses most scientists in the academe as slave labor (the long lengthed phd programs, if you go back to their origins, seems to be constructed not out of need but rather corrupt motives) part and parcel with it we have deep cartelization in our economy which inhibits science and engineering, things like the Bayh-dole act which decrease science and engineering, etc.. BTW, China under Xi has been deeply politically and economically centralizing in recent years, part and parcel with this has been to move their academe to the sorts of centralized model we have so as to make it more of a tool of special interests groups in the national center which means they may very well start to develop the same pathologies as ours soon.