Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China's Rise

"It's a lot easier to solve poverty for 20 million people than it is to solve the low-income problem for 900 million people."

Welcome to the 37 new people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 7,047 smart China-curious folks by subscribing here:

Scott Rozelle (Stanford professor, co-director of the Stanford Center on China's Economy and Institutions, all-around legend) came on the ChinaTalk podcast to discuss his recent book Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise, co-authored with Natalie Hell. What follows is an abridged and lightly edited transcript of our discussion on the problems facing "low-income China."

But before we get to the transcript, I wanted to announce the first annual ChinaTalk Student Research Symposium! If you’re a graduating senior or masters student who has written a thesis that incorporated Chinese language sources and would like to discuss your research on the podcast for 15-20 minutes, send me your undergraduate or masters thesis

Is China the Next Mexico?

Jordan: China, while the second-largest global economy, has one of the lowest levels of education on the planet, trailing nearly all middle-income countries in percentage of high school and college graduates. 70% of the labor force is unskilled, meaning less than a junior high education. Scott, why in 2021 should the world be focusing on rural China?

Scott: That's a big question. It's been a book that tries to bring together all of my research and experiences in rural China, since the mid-2000s.

What I discovered is one of the biggest problems in China that no one knows about is exactly what you said: China has the lowest level of human capital in the entire middle-income world. I don't care if I'm talking at Tsinghua University, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce, or an NGO in Shenzhen, people gasp when they hear this. I think that at this stage of development, as they're trying to move to high-income, this is potentially going to be a big challenge.

Jordan: So what is the worst-case scenario of how this all unfolds?

Scott: I’m a development economist, right? I squat in villages, do research and talk to teachers and parents and doctors, so you're probably talking to the wrong guy on this… but when I do discuss this with political scientists or macroeconomists, they say, “What if China follows Mexico’s path?”

When I was in grad school in the ‘80s, Mexico was called the next Taiwan. It had grown for several decades in a row at a very rapid rate. OECD, the organization of economic cooperation development (that's the rich man's club in the world), they allowed Mexico to enter. Mexico had made it, right?

Jordan: 70 years of one party rule! There's plenty of plenty of common points.

Scott: Exactly. It was rapid growth and then they hit this wall. And if they hit this wall, what are the implications? They're a big engine of growth, so world growth slows. Legitimacy in China, to the Chinese government, is through its growth. If it stalls, how do they gain legitimacy?

These are the kinds of things that I worry about. The kids and the families that I know in rural China are going to be the ones that take the first hit. So I think there's lots of implications here.

Jordan: I want to explore the Mexico comparison a little bit, Xi Jinping just like two days ago was bragging about all these gangs that he's been able to crack down on it. But the fact that he's able to say he cracked down on [3,600 “mafia like groups] means that there were a whole lot more than [3,600 ganges- to crack down on in the first place. In the past few years, a few of the potential faults that you write about if China isn't able to increase its workforce and find decent jobs for the common folk who haven't made it to the cities yet is crime and social unrest. What are your thoughts about criminal enterprise in China and how it feeds into the themes that you talk about in your book?

Scott: In the 1980s in Mexico, there was no crime. It wasn’t the Mexico that we know today. The Mexican government talked about what a safe place it was as they were growing very fast. Of course, everybody had a job. Everybody was employed. And that's China today. China's not a dangerous place, but Mexico wasn't a dangerous place in the 1980s.

What happened in Mexico, of course, is China happened, right? Wages in Mexico went up, as everybody got employed and the factories in Mexico decided to move. The maquiladoras moved to China. They moved back to the United States. They moved to elsewhere in the world and suddenly, within a couple years, 10 million people lost their jobs and that was 20% of the Mexican labor force.

What did those 10 million people do? About half of them or a third of them went across the border to the U.S. China's not gonna be able to do that. The second thing is they went into the informal economy; they started hawking fruit on the street, washing car windows, doing landscaping. The third thing, is they went into organized crime… Most people in Mexico don't want to be in crime, but there's going to be a share of people when your future looks so bleak you're going to finally make a decision: “I need to go this way or live in poverty.”

That's the decision that they made and look at Mexico today. So that's what I'm worried about as China starts to polarize. In China, 500 million people are facing long-term challenges in finding a job. Can China control the crime where Mexico wasn't able to? I would rather see them not having to control crime by instead having these people become actively engaged in the workforce.

Li Keqiang said, “let’s have a “地摊经济,” that means farmer-salesmen, the ones that squat in the markets and sell fruit. Street vendors. He actually said there's 500 million street vendors that make 1000 yuan ($150) or less per month. That's higher than the poverty line for sure. But it's still very low income.

Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and Ireland don't have huge crime rates because as they moved to high income, the entire labor force was able to participate and be part of the big economic movement. That's the difference.

The Literally And Figuratively Left Behind Children of China's Countryside

Jordan: Scott, how do we reach this point?

Scott: If a mom has a baby in her arms, and you ask her, “What's your aspiration for this baby?” what do they say?

We actually asked 1,800 moms that question and 1,750 of them over 95% of them said, “I want my kid to go to college.”

Then the kid grows up and their mom wants them to go to college but they were raised like they're a farmer. So they’ve been kept safe and strong, but they haven't been stimulated. Then they go into very poor quality nursery schools that are private and expensive. Then they go into compulsory school K-to-9, and it's like the U.S. with school districts with very low property taxes… it's a really poor school district and big classes and poor teachers. Of course, they're in a system that has an exam, a single exam for the whole country. At the high school level it’s called the zhongkao. This kid, whose mother wanted him to go to college, is struggling to learn seventh-grade math and he suddenly looks at himself and says, “There's no way I'm going to pass that high school entrance exam, much less the college entrance exam.”

There are only positions in academic high school for half of rural kids. And so they get to this point and they say, “Do I want to go on in this school system?”

They drop out. They get to junior high and they barely know how to read and they barely know how to write. They're very disciplined. They're great workers for factories. That's what makes great factory workers: you're numerate, literate and disciplined.

But if you want to become a bookkeeper for an accounting company or a financial assistant in an investment firm or a bank, you better know math, science, English, Chinese, and computer skills. That's gonna get you a job in high-income economy. And these guys just don't. And so the little baby whose mom wanted them going to college is she's out of school by ninth

Jordan: Part of the justification for the One Child Policy was the idea that the state could concentrate its resources and raise the quality of the educational opportunities for the fewer kids that would be going through the system. Why didn't that happen? Or why did it only happen in certain regions?

Scott: China has a decentralized education system, social services, health care, unemployment pension… everything. Education is decentralized just like the United States. In fact, we have 40,000 school districts in the U.S.—China has 40,000 school districts. It's exactly the same. When school districts are locally funded and you don't have a tax base, the Bureau of Education has to make some hard decisions… or the county, which is above the board of education, says, “I have really scarce resources. Do I want to spend it on rural kids and their education? Or do I want to build a park and redo the infrastructure in town where urban residents live?”

And then you say, “What happens if I give these rural kids a really good education?” They all go to high school. If you take a hundred kids in a rural County to high school, guess what? Nobody comes back. Less than 5% of the people come back. You're taking these scarce, local resources and helping China, at large [but not the county]. This is why it’s totally incumbent on the central government to completely redo the financing of rural schools.

Jordan: Scott, it's really about more than money though, right? New York State spends $24,000 per student and does not have the best educational outcomes in the nation. You wrote a paper showing no significant benefits from attending model vocational high schools, as opposed to regular vocational high schools, despite their substantially greater resources. Aside from just the tax base, what else is broken?

Scott: My colleague from the School of Public Health at Emory, he had been a Stanford professor and was one of my mentors when I first started as an assistant professor, he said, “Scott, I think the problem starts way before these schools we’re visiting. I think they start in pregnancy and with kids that are zero to three.”

We’ve just written a meta-analysis of every paper that's looked at the cognition, the language, the social-emotional skills of children in rural China, and we're finding that almost half of them have delays. These are delays that are caused because of the absence of modern parenting. They don't stimulate their kids. They love their kids but they don't know how to raise their kids to be a college student.

China has a saying it's called “三岁看大七岁看老“, that means, approximately, “At three, you can see the future.” James Heckman, Nobel prize winner from the University of Chicago, has a paper that says, “Test the kid at three and I'll tell you what his sat score will be when he's 18.”

I think the fundamental problem is that China grew too fast and these rural parents see social media, see TV, and see the cities. That's what they want for their kid, but they don't know how to get them there.

Parochial (and National?) Short-sightedness On Rural Poverty

Jordan: Xi made it a very public central goal to eliminate poverty. So it's not like he is completely forgetting about every issue on the rural Chinese agenda. Do you have any sense of why certain goals like “eliminating poverty”, get more attention than stuff like myopia or malnutrition or early childhood education?

Scott: I’m all for getting rid of poverty, but getting rid of poverty was easy, right? Who's poor in China today? I'm not talking about in 2030, but today, right? It's the elderly without kids. It's the disabled, and of course it's the non-Mandarin speaking minority groups that have trouble integrating themselves in the economy. Up until now, if you have a strong body and you can speak the local language, you're going to have a job and you're not poor.

I don't worry about poverty. Terry Sicular and her colleagues have a fabulous paper written with national data that basically shows China has a huge middle-class, it's 400 million people, but they have 950 million people that are in low-income.

It's a lot easier to solve poverty for 20 million people than it is to solve the low-income problem for 900 million people.

The myopia problem, the nutrition problem, the intestinal worm problem, they're invisible problems. China's trying to develop 2,000 county seats, fourth and fifth tier cities, into little urban centers. They're trying to make 2,000 Cincinnatis, right? I don't see what people are going to do there. There’s not going to be any manufacturing in those cities. There's not going to be any construction in the long run in those cities… and everybody's low income! There's not going to be any demand for services.

Jordan: One of the striking examples in your book is of farmers regularly deworming their farm animals, but not even conceiving that this could be a problem in humans. Also these eye exercises (which I've seen done in China) are scientifically proven to be completely useless. Which is even more mind-blowing when you can just buy glasses for 20 kuai and this problem is solved. So aside from the obvious interventions of fixing water supply and whatnot, how would you rejigger the Chinese bureaucracy to get it to pay more attention to these invisible but critical problems?

Scott: So the first problem is nutrition problems, especially anemia. It’s not stunting. It’s not being severely underweight. It's a problem of micronutrient deficiencies… not enough iron, among other things.

We went out and we tested tens of thousands of kids. We found out that 40% of rural kids in many different provinces all had this condition. It's invisible. We then went and we did a vitamin per kid per day. We gave teachers the vitamins and gave teachers a boiler. Lo and behold, the anemia went down and guess what?

The Bureau of Education doesn't really care about nutrition problems, anemia. That’s what the Ministry of Health does, not the minister of education, but when student’s anemia went down their grades went up. Ooh, we certainly got their attention! We then had a connection over in Gansu, the next province over, so we went to Gan Su and said, “Hey guys, in Sha’anxi, we showed that a vitamin a day can reduce student anemia. And it makes their grades go up! They said, “That is in Sha’anxi. That doesn’t work in Gansu.”

So we did another intervention there. So we finally do this in three or four places, and we're having this conversation with Vice Premier Liu Yandong and she came out and said, “We gotta do something about it.”

One year later, there's a national nutritious lunch program for 26 million kids funded at three to four billion yuan a year. It's still underfunded, but it's there. So that's how you solve this problem.

But that's not a solution anymore because we can't have these direct conversations with the top leaders anymore.

Jordan: Getting to the crux of the matter of you—white guy, Stanford professor—being the one to drive this change (or you have a team, there are Chinese collaborators): But why isn't Chinese academia and the Chinese government addressing this without REAP’s involvement?

And what do you think the Chinese government is losing by cutting off these sorts of interactions, as it seems they've done in the past few years?

Scott: Research is just like schooling, is just like pensions—it's locally funded. Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen give their professors a lot of money to work on problems of Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Gansu doesn't have money to spend on rural education research!

There's just nobody to do it. It's a lack of supply that leads to a lack of demand for research on these issues from professors. We've been very lucky to be at Stanford and we have lots of great supporters. Most of them are Stanford alums or parents of Stanford students. They've been great supporters. We then take that support and pair it with people on the ground. I don't go to the village and interview these kids. We have to have local collaborators. When we say, “Do you want to do this?” Oh, our local collaborators are passionate about this work!

So that's the problem, right? It's an invisible problem. If you say, “Let’s go raise the IQ of 10 million babies who aren’t developing well,” when does that come to fruition? About 2045, right? That's when they'll be through college. Even this leadership that doesn't have to be elected every four years, I don't think they're thinking out that far.

Jordan : We've done the is “China a longer-term player than the U.S.?” debate a few times on ChinaTalk. The easy, sexy stuff is investing in semiconductors. But it’s on these issues where the real work gets done.

Scott: And high-speed rails that you put your name on, right?

Jordan: This is the exact sort of thing where if you were making the argument that China was more strategic and more far-sighted, this would be where all the money would be going to, because if you're playing a 50 year game, the prospects of SMIC making it to the next node is far less important than whether or not 300 million people are going to be able to read write and write, if you’re talking about your country’s economic future.

Scott: 100%. It's a hard thing to get your mind around and you see the problem.

I compare them to Mexico and Turkey and South Africa. They say, “China's not Mexico. We're different from them.”

I say, “But you aren't doing the same thing South Korea and Ireland did.”

Then they say, “We're not the same as South Korea and Ireland.”

And you know what? The fact is they might be right, Jordan. Maybe this isn't a problem for a huge country like China. They have millions and millions of college grads. It's still a small portion of their population. Maybe it's not… but maybe it is.

If there's a small probability that this could really undermine the growth of China and undermine its social stability and it's peacefulness, for heaven sakes, let's buy insurance right now! Let's not put, I don’t know, $3 trillion into high-speed rails over the next 15 years. Let's put at least part of that money into 0-3, 4-6, K-9, high school. How about let's focus on retraining adults who are getting laid off in the factories?

Why Land Reform Should Be The #1 Topic Of Discussion

Jordan So, on the privatization of rural land…giving urban house dwellers the deeds to their lands was the greatest wealth transfer in global history. Why is it such a big deal that the farmers don't have real deeds to their land?

Scott: It relates back to the problem of the new dual circulation economy, which is: “We’re not going to rely so much on foreign demand for our products. Trade is gonna start to become less and less important. So we've gotta have our own demand drive growth.”

900 million people are low income and guess what? They don't spend money on services. Why is that? It's because they don't earn a lot of money in the first place, but then once they earn it what do they have to think about?

They think: “I could buy services or buy consumption goods now… or I could save it. Why do I need to save? If I have a boy in my family, there's a sex ratio problem, then I need to save 500,000 yuan just to get my boy married in 20 years if he's one year old or 10 years if he's 10 years old. Also, if I have health insurance, if I cut my finger or get a stomach ache, I can go get treated almost for free. And that's a great step forward. But if I get cancer or have a heart problem or have any sort of other serious health problem…”

Catastrophic health coverage isn’t perfect in rural China. In fact, you often have to pay an advance to go get coverage in rural areas. So you have to save money for the chance that there's a catastrophic illness.

Of course, retirement. The average rural person gets 65 yuan a month in pension payouts. The average urban person gets 3,000 a month.

But you could have this insurance policy, your land. If you have land, you have insurance, right? You have collateral to get a loan. So suddenly you have this asset that provides at least partial insurance which relaxes the savings motive and encourages domestic demand. I don't know why people don't think about that. And, you can't say the P word, right? “The privatization of land word”… It's just not even… it's not even on the table.

Country Driving

Jordan: Say I have a month, what is my dream rural China road trip?

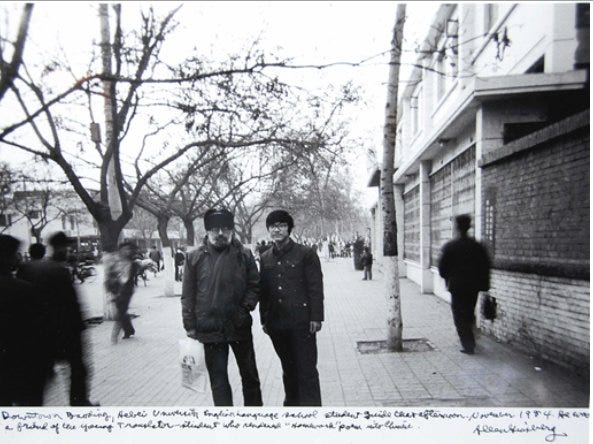

Scott I would do it in early-mid-September. Start in Gansu and just head South towards Guangxi. Go through Ningxia, Southern Sha’anxi, Sichuan, Chongqing, and Guizhou. Fall is the best weather in China. You can stay in very nice hotels in the County seat. There's lots of recreation areas in these areas, but then also make sure that you get out and walk through the villages.

Just stop on the side of the road and walk into the village. The great thing about China's villages is they’re open everywhere. You don't need any special permit or anything for them. And people are so nice. They'll invite you into their home and they'll tell you their stories. So you can have a great time: stay in nice hotels, eat cheaply, and see you go all the way from North Asia to the tropics.

Jordan: Scott Rozelle, what a pleasure. Thank you so much for coming on. ChinaTalk

Scott: Jordan, we look forward to lots of interaction with you in the future. You're my favorite ChinaTalk guy. Thanks.

Tweets of the Past Two Weeks

If you like food videos, this channel is a must-watch. She also has 500k subs on YouTube! Some videos have English subtitles.

Yangyang is such a good writer even GT gives props. Give this woman a book deal!