America, are we cooked? To discuss, we have Peter Harrell, former Biden official and host of the excellent new Security Economics podcast, Kevin Xu, who writes the Interconnected newsletter, and @overshootMatt Klein, author of Trade Wars Are Class Wars and

substack.We discuss…

The chaotic implementation of new tariffs and their impact on international alliances,

Whether China will be able to capitalize on this opportunity,

Why the US dollar hasn’t strengthened in response to Trump’s tariffs,

Whether allies will choose nuclear proliferation over an unreliable USA,

The resilience of America’s strengths despite governance failures.

Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app.

Great Changes Unseen in a Century

Jordan Schneider: Peter, how do you feel the country is doing?

Peter Harrell: I actually don’t think we are cooked yet. There are enormous underlying structural strengths here in the United States that make me quite bullish about the future of America.

I should acknowledge that you caught me during a week of vacation in Southern Utah, where the weather is gorgeous and the rocks are magnificent. It’s hard to see us being cooked this week. If you ask me next week when I’m back in the office, I might have a different view on the situation.

Kevin Xu: We’re not cooked yet, but that probably implies some cooking is happening as we speak.

One line that got me thinking came from Josh Wolfe of Lux Capital, who runs a firm that I really admire. Early in the pandemic, he said, “Failure comes from failure to imagine failure.” For the sake of saving America or ensuring we’re not cooked, it’s probably useful to think hard about what “cooked” looks like so we can avoid going there — the aversion mental model of Charlie Munger.

This is something I think about more these days than before. That’s not to say we are cooked. There are many things in my personal and professional experience that suggest America remains special, if not exceptional, for all the right reasons. My current mindset focuses on imagining potential failures precisely to prevent them from happening.

Matt Klein: While I agree that we are not yet definitively cooked, we are definitely cooking. I concur with Peter that there are many long-term structural reasons to be optimistic about the United States economy and society. However, we have an administration that seems determined to attack all those strengths simultaneously. We’ve only been at this for about two and a half months.

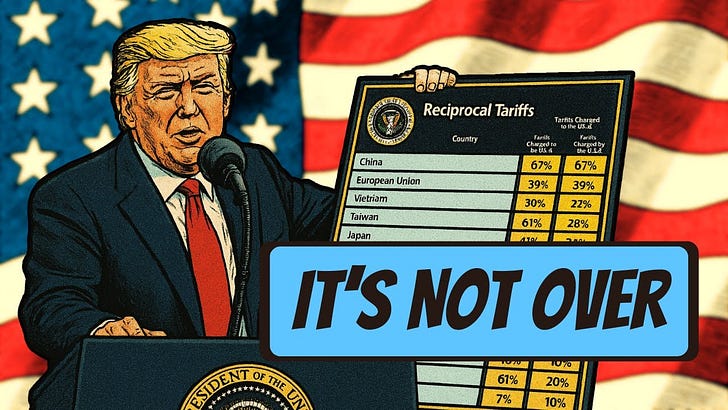

If we were looking solely at the tariffs announced last week, I would agree that while they have negative consequences — clearly demonstrated in market reactions — that’s not the main reason to be concerned. What’s revealing is how these specific tariffs were chosen and rolled out, which is revealing of the overall governance process of this administration.

The Washington Post did thorough reporting on how the process actually occurred. Various teams of staff at different agencies — USTR, Council of Economic Advisers, Commerce, and others — were simultaneously developing methodologies for justifiable, reciprocal tariffs. Substantial staff work was being done. They were asking US companies abroad about their challenges and conducting extensive research.

Yet the final decision, made just two or three hours before the announcement, abandoned all that work in favor of the most simple-minded, least rigorous approach — a formula based on essentially two variables: exports and imports of bilateral goods with each country. This approach isn’t justifiable theoretically or in any other way. After people independently deduced what had been done, administration officials repeatedly denied it before eventually admitting the truth.

What does that tell you about everything else? This comes after we’ve already seen attacks on scientific research, extreme hostility toward foreigners entering the country, and a changed approach to international relations that includes threatening some of our closest allies. The tariffs imposed capriciously on Canada and Mexico are particularly troubling, considering this same administration negotiated and ratified a trade treaty with them just five years ago.

Looking at the broader context — the attacks on the rule of law, for instance — raises serious concerns. You can’t put a GDP value on the rule of law, but historically, the confidence that people can safely prosper in this country as long as they don’t harm others has been one of America’s structural strengths. When you add everything up cumulatively, you can understand why people might be worried.

Is the market reaction purely about the tariffs? Or is it a realization that all these things are adding up and potentially creating serious costs? That’s the big open question. We haven’t crossed the point of no return by any means, but there’s reason to be very concerned about whether we’re “cooked” or not.

Peter Harrell: Matt, don’t forget they also tariffed the penguins. In addition to tariffing the penguins, we then saw Howard Lutnick go out and justify it on the basis that maybe they would somehow get involved in rerouting trade from China or some other such place. This whole story of tariffing the penguins and then claiming you had a rationale because you’re worried the penguins will get into the transshipment business really doesn’t inspire confidence in current trade policymaking out of the administration.

Matt Klein: Right, there’s a decent chance they actually used a chatbot to come up with the exact tariff formula. Someone did a test — if you asked the free version of ChatGPT or Claude, how would you come up with it? They basically came up with exactly what the administration said, including basing it on internet domains as opposed to customs jurisdictions. Hence, the penguins.

Peter Harrell: Let’s also keep in mind this is an administration that has canceled most of its paid subscriptions to major outlets. Presumably, that is why they’d be using the free version of ChatGPT rather than paying for at least something that might have calculated the formula correctly.

Jordan Schneider: How weird can the next four years get? To what extent is this reversible by a Democratic Congress two years from now or a new president four years from now?

Peter, you were part of the “Let’s Make Friends With Our Allies Again” team in the early years of the Biden administration. What was that experience like?

Peter Harrell: I should begin by saying that I actually believe there are enduring, long-term American strengths. We have a very entrepreneurial culture that, by and large, values education quite highly. We have a pretty hard-working work ethic here. Even if the Trump administration is cutting federal R&D spending and grants, there’s a tremendous amount of private R&D in this country.

We start with a number of very strong underlying societal, business, and commercial strengths. The question is really, against these underlying societal strengths, how much damage can things like the very chaotic tariff policy we are seeing do?

I break that down into two different buckets. One is economically, how much damage can it do? Here, I don’t think we’re at the end of the story. We’re recording this on Monday morning. Maybe the market reaction is still getting through to Trump and they will begin to change course.

Particularly on the tariffs, I’ve argued for a couple of months now that this is all illegal. The statute that they are using for these tariffs simply doesn’t authorize them. As of last week, we are now seeing litigation against these tariffs, and we are more likely than not going to see the courts begin to curb some of these tariff powers. He’s still going to have a lot of tariff power even if the courts do curb them, but the courts will likely insist on some rational order being brought to the tariff agenda.

But you asked about the global damage. Aside from the economic harm, there’s also a geopolitical set of actions here. It’s really angered the Europeans, Japanese, and South Koreans. How does this impact our alliance structures?

There’s likely to be some durable damage to our alliance structures. Our Western European allies aren’t going to pivot to China — they understand it is not in their economic or social interest to join themselves fully at the hip to the Chinese. That would hurt their economy too. They’re going to need to raise some barriers of their own to China to prevent their own industries from being hit.

They will see Americans as less reliable allies going forward. That doesn’t mean they won’t cooperate. The analogy I’ve been using is that in four years, post-Trump, whether it’s another Republican or Democratic presidency coming in, many of our core allies will view it as, “Well, you just went through a divorce with us. We’d be happy to come up with a more amicable custody arrangement and see if we can be on better terms at parties, but we’re probably not going to move back in together."

This will be an enduring hit to our alliance structures, though it doesn’t mean that a future administration won’t be able to get a good degree of cooperation on areas of mutual interest.

Matt Klein: I would just add that this is happening at the exact same time, particularly with Europe, where we’re doing a complete heel turn on foreign policy grounds and essentially abandoning a lot of what they consider to be their core strategic interests. It’s not just the economic approach that would be offensive to them, but when paired with the approach to Ukraine and Russia, and the possible withdrawal of American commitments to NATO, and of course, the threats to annex Greenland from Denmark — viewed collectively, this creates some long-term damage. The damage extends to Canada too, which has historically maintained a very close relationship with the US for well over 100 years, and that relationship now seems to be severely damaged.

Jordan Schneider: How should we read the rhetoric we’re hearing from Mark Carney? Here’s a quote from him:

The global economy is fundamentally different today than it was yesterday. The system of global trade anchored on the United States that Canada has relied on since the end of the Second World War, a system that, while not perfect, has helped to deliver prosperity for our country for decades is over. Our old relationship of steadily deepening integration with the United States is over. The 80-year period when the United States embraced the mantle of global economic leadership, when it forged alliances rooted in trust and mutual respect, and championed the free and open exchange of goods and services is over.

Peter Harrell: There is clearly both a tactical and strategic part to Mark Carney’s comment that the relationship is over. Tactically, Carney is in the middle of a political campaign in Canada, so there’s a domestic political dynamic. He wants to send a signal domestically that he will stand up to Trump and won’t take being belittled the way he thought Governor Trudeau was constantly belittled by Trump.

He’s also signaling to the Trump administration, “We are prepared to push back. We’re not going to take this lying down. While we would like a negotiated solution, we are going to stand up.”

But there is also a deeper strategic point he’s making to Canada — “While the United States is very likely to remain our most important trading partner and our most important security partner, we here in Canada need to begin hedging our bets. We can’t be dependent on the United States to the extent we have been over the last 20, 25, or more years."

He’s sending a message that Canada isn’t going to cut everything off with the US — he does want to get a deal — but Canada will be looking to increase its trading connectivity with Europe and not just rely on the US market. Canada probably isn’t going to be reflexively in favor of agreeing to many of America’s asks when it comes to China. Canada will take its own interest with China into account. They don’t want to be flooded by Chinese exports either, but they might be looking for Chinese investment if their trading relationship with the US is weakened. They need to figure out where they can get capital. I hope they don’t go down that road, but Carney is beginning to signal he’s got to figure out what their long-term economic interests look like in a world where they see the US as a less reliable partner.

Matt Klein: The takeaway is that this represents a long-term cost — a long-term cost to Canadians, a long-term cost to the US. This is a standard textbook situation: you want to have the closest relationships with your immediate neighbors because distance is a challenge. It’s beneficial to have integrated manufacturing, finance, and other sectors between Detroit, Windsor, Toronto, and other border regions. If the conclusion is that Canadians think it’s better not to maintain that integration, then everyone will be worse off than in the alternative scenario.

Jordan Schneider: Kevin, do you think China will capitalize on this?

Kevin Xu: The Chinese economy still has many of its own problems that are in the process of being addressed. These include the property bubble and a weak consumer economy that they’re trying to stimulate.

Headlines are already emerging about stimulus measures, ratified from the National People’s Congress in March, now being accelerated from a deployment perspective now that the tariff numbers from both the US and Chinese sides are known. China needs to do many things for itself in this precarious situation.

There’s always this reflexive narrative — every time we consider whether the US is doing well or not, we automatically wonder if China will immediately fill that international space. I am personally very skeptical of any country being willing or able to fill the international role the United States has occupied for the last 30-40 years if the United States steps back.

What other countries have observed is that being the hegemon, being the global superpower that handles a lot of responsibilities, can be a thankless proposition. The tariffs have demonstrated to all countries that retreating to take care of your own national interests is now the fashionable approach. It’s acceptable to have no hegemon for perhaps the next 10 years. Everyone takes care of themselves.

Whether that’s the economically optimal outcome, we all know the answer. However, politically speaking, that may be the most preferable path for all countries’ leadership, including China. There might be anecdotal evidence where China fills spaces or programs where USAID used to operate but no longer does. From the Chinese perspective, they’ll be very tactical about how they fill that vacuum and let the rest of the world, or the chips, fall where they may if we are indeed entering this new world order — or lack of order — which I believe we are stepping into right now.

Matt Klein: I’m curious what you make of Xi Jinping appointing the ambassador envoy to the European Union in Brussels — someone who had previously gotten in trouble with Europeans for suggesting the Baltic States didn’t really have a legal right to exist.

Jordan Schneider: This seems odd considering it would be a great time for the Chinese government to improve relationships with Europe, especially given what the US is doing. What do you think was the rationale for that?

Kevin Xu: First of all, we give Chinese foreign policy making far more credit than it deserves. There’s a narrative that portrays their actions as part of a masterfully executed 20 or 30-year plan, but that’s completely misinformed. Every foreign policy, regardless of political system, has a domestic component. Being strong and pro-China from a foreign policy perspective still has a lot of appeal.

We should be careful about over-interpreting the strategic nature of many of these moves. This could simply result from random internal political dealings — perhaps this official was up for a position, and this was what was available to him. His previous statements may not have factored into any grand strategic preference from the American perspective.

The EU-China relationship is probably the most interesting and dynamic one to watch. There isn’t an obvious trajectory where, because the transatlantic alliance has deteriorated, a Eurasian alliance will suddenly emerge. We’re in an era where most nations are primarily looking out for themselves.

Jordan Schneider: It’s worth recalling that China also has a recent history of bungling major policy tests with the COVID lockdowns. Xi is getting older, he’s a large man, formerly a smoker, and there’s no succession plan yet. That’s the risk people forget when they view China as an ocean of stability.

The CCP’s track record for power transitions is not particularly excellent. Sooner or later, we’ll witness that system trying to work around this issue, which could have big downside risks. For all the jokes about Trump’s third term, I don’t think we’ll go that far in America.

Peter Harrell: As we observe the market turmoil and chaotic tariffs, it’s easy to criticize Trump’s policies. Trade policy specifically is unlikely to yield positive results either in the near or long term. However, there is a smarter way to reform American trade policy. Matt has written about this over the years. A more thoughtful approach to American trade policy could actually benefit the United States without causing such chaos.

While we’re currently experiencing maximally chaotic Trump policies, there will likely be some initiatives from Trump and Congressional Republicans that will leverage American strengths and prove beneficial. As someone who served in the Biden administration, I acknowledge the criticism of our ability to actually build things over the last four years. While some criticism is exaggerated, I believe there is merit to the idea that we need a deregulatory agenda to facilitate more construction in the United States.

If Trump succeeds in reducing barriers to physical construction at federal, state, and local levels — whether for manufacturing facilities or infrastructure — that would be positive. Additionally, while I’m skeptical of tax cuts heavily favoring the wealthy, some stability in our tax regime could be useful. We obviously need to address this issue this year.

So while I’ve been critical of Trump’s trade policy and other aspects of his approach, including on Ukraine, I believe we may see some more valuable policies emerge over the next couple of months.

The Moron Risk Premium

Jordan Schneider: You need competent staff to create legislation, executive orders, and regulations. If we’re experiencing a complete policy lobotomy for the next four years, does that mean even the potentially positive initiatives in the Trump agenda won’t be able to flourish?

From 2016 to 2019, there were relatively few crises. With COVID in 2020, Trump might deserve a B+ grade, all things considered. Five years later, we’re forgetting about some of the more questionable pandemic suggestions. But if this is how the administration functions during a relatively calm period, four years provides ample time for outlier events to occur. The administration’s ability to navigate and respond to external shocks — let alone self-inflicted ones — has significantly diminished in my estimation based on recent weeks.

Kevin Xu: I’d like to expand beyond the Loomer situation specifically, which I know you discussed in a previous episode. This relates to what Matt mentioned earlier about one of my personal indicators of the “cooked or not cooked” divide — the arbitrariness in our civic life.

One of the enduring strengths of the American system isn’t just the rule of law broadly, but specifically due process. The fact that any decision, large or small, follows a process that’s impersonal and largely apolitical. Whether you’re getting your Social Security check or renewing your driver’s license at the DMV — which may be inefficient but treats everyone identically — this extends to the other extreme regarding what influences the hiring and firing of important government officials.

Having served as a political appointee, as Peter has too, we understand we serve at the president’s pleasure. Being fired isn’t catastrophic for us. However, civil servants are different for very specific reasons. When institutions that traditionally uphold due process are systematically undermined, that pushes us toward the “cooked” side of the spectrum.

What Laura Loomer has illuminated as a circumvention of due process troubles me most — not specifically who was fired, which I don’t have a personal assessment of, but the process represents the biggest warning sign.

Matt Klein: This is consistent with how they’ve been rounding up people who are either legally in this country or whose status may be uncertain, then immediately deporting them to places like El Salvador before they can prove their status. You could do that to a U.S. citizen, and if you act quickly enough, they can’t prove their citizenship either. That pattern is concerning.

Kevin Xu: Exactly right. There’s anecdotal evidence around me now of people who carry extra documents despite being American citizens when traveling, such as going on a cruise. They think, “I don’t look the way some people might expect, so I need extra documentation to ensure I can return to my own country.” At the ordinary citizen level, this erosion of due process has already taken root.

Peter Harrell: Regarding the layoffs — setting aside how the recent NSC layoffs occurred — let’s consider the dismissals of career staff across agencies. This will adversely impact the Trump administration’s ability to pursue goals that many of us on this podcast and those listening would actually support.

A couple of weeks ago, BIS Undersecretary Kessler, who oversees export controls at the Commerce Department, spoke at a conference about ramping up export controls enforcement on China — something I would support. However, the administration has now laid off a large number of BIS export control staff. As a straightforward American, I struggle to understand how they expect to increase enforcement while eliminating most of the staff.

This will have two impacts — the more important being the effects on Americans who believed they were entitled to procedural rights only to discover they don’t have them. Additionally, the Trump administration itself will encounter barriers to pursuing even broadly supported goals because it won’t have the necessary staff to implement them.

Jordan Schneider: Matt, do you have any leading economic indicators for us?

Matt Klein: The most leading economic indicator would be asset prices. Academics refer to this as both a mirror and an engine. On the other hand, it tells us people are obviously less optimistic about the outlook for various reasons and more uncertain. On the other hand, high and rising stock prices have been a support to both consumer spending and business investment.

When companies have higher stock prices, they feel more comfortable hiring people and investing in capital expenditures. They’ll now be less comfortable doing those things, which could have self-reinforcing real economic effects. Consumers who look at their asset portfolios and think, “I’m doing well, I can afford to spend more of my income,” will be less inclined to do so.

Taxes are due next week, and people who make quarterly estimated payments will need to write a big check. These payments are based on what you earned last year, but you have to pay from what you have now. This will be unpleasant for many people.

The hard data we’ve had on inflation, unemployment, and other indicators have been acceptable, but that information is already outdated. The most recent employment data from mid-March was actually quite good in some ways, but much has happened since then. Most other data we have is from February, making it difficult to assess the current situation.

Survey data have been quite pessimistic, though with variation — some surveys look worse than others. The economic impact remains unclear at this point. The situation appears concerning, but that’s somewhat anecdotal and easy to say when stocks drop 15% in three days.

Jordan Schneider: Peter, do you have a nuclearization take for us?

Peter Harrell: The perceived lack of reliability of the US as a security partner will encourage a number of US allies and partners to take steps to increase their own self-defense capabilities across different vectors.

In recent weeks, several Eastern European Baltic nations have begun moving toward withdrawing from the treaty that bans landmines. They’re clearly signaling that, given Russian aggression and America’s potential pivot on Ukraine, they need more defensive weapons, including historically criticized ones like landmines. We’re already seeing evidence of countries revisiting aspects of their defense posture in light of these new geopolitical realities.

It would be quite rational for countries like Japan or South Korea to begin quietly considering what developing an independent nuclear capability might look like as a deterrent against Chinese or Russian aggression. Whether or when they will take that step remains uncertain, but it would be rational for them to begin contemplating it.

Similarly, a nuclear debate in Europe is emerging, but it will likely begin quietly before gaining momentum.

We are already seeing it, indeed. The question there is whether the issue will be developing an independent British and French nuclear umbrella that extends across Europe, or whether Germany needs its own independent nuclear capability. As Matt notes, we’re already witnessing that debate.

Matt Klein: Right. The Polish government has said that they now want to develop nuclear weapons.

Peter Harrell: Whether they’ll go nuclear in the next four years is uncertain, but we’ll likely see progress toward nuclear capabilities in Europe.

Kevin Xu: Returning to economic indicators, something that perplexes me — a factor on my own “cooked or not cooked” indicator — is the dollar’s value. Since the recent policy announcements, the dollar’s value has actually decreased slightly, which contradicts the theoretical best-case outcome of these policies.

The theory suggests that as trade barriers rise, the dollar should also strengthen against other currencies. This would shield some erosion of American consumers’ purchasing power while putting the government in a favorable position to refinance debt at lower rates, thereby reducing the deficit. However, this hasn’t happened yet. I’m curious about your interpretation of the dollar’s reaction. I have my own theories, but I’d like to hear your thoughts first.

Matt Klein: You’re right that the dollar’s movement was unusual and different from what many had anticipated. During the first Trump administration, officials claimed tariffs wouldn’t be as inflationary as critics thought because currency values would absorb some of the impact. Looking at what happened in 2018-2019 when they implemented tariffs, the dollar did rise to offset some effects. Earlier this year, when tariffs were announced on Canada, Mexico, and China, the dollar appreciated against the Canadian dollar, peso, and yuan, which seemed to confirm this pattern.

The textbook reasoning suggests that tariffs make investments in the United States relatively more attractive for selling to the US market compared to investments abroad. This should create financial inflows into the United States that strengthen the dollar. Yet that’s not what happened this time. Even with very large tariffs — essentially increasing our overall tariff rate from roughly 2% to 25% — which theoretically should make investment in the United States much more attractive, the dollar declined.

This outcome aligns with concerns about economic instability. Whatever theoretical attractiveness might come from these trade barriers has been offset by other factors. If investors believe the tariffs won’t be permanent or are uncertain about what the final levels will be, why would they commit to long-term investments?

There are arguments both for and against tariffs potentially boosting investment in the United States, but most would agree it depends on a commitment to policy consistency. This level of uncertainty is destructive to investment, compounding the fact that the tariffs themselves will negatively impact many existing investments.

Peter Harrell: What happened in the UK in fall 2022 provides an instructive parallel. During the very short-lived Liz Truss premiership, they introduced what was called the “mini-budget” — though there was nothing mini about it. They implemented major changes to taxes and spending that many considered irrational.

Part of what concerned observers was that they bypassed normal procedures established for presenting a budget in the UK. They have an Office for Budget Responsibility that’s supposed to provide independent forecasts, which they essentially ignored. As a result, British interest rates spiked dramatically and, despite rising interest rates, the pound sterling declined.

This prompted comparisons to an emerging market currency crisis. Someone coined the phrase “moron risk premium” — meaning the additional risk factor wasn’t about inflation outlook or deficits, but about the competence of the people in charge.

Something similar may be happening here. Whether the dollar will decline significantly from this point is impossible to predict, but the fact that it didn’t strengthen as expected, is indicative of something having happened

Jordan Schneider: The comparison of America exhibiting emerging market economy-level policymaking is perhaps the most succinct way to tie all this together. The problem is we haven’t had many global hegemons who transitioned from being functional to deeply dysfunctional.

Peter Harrell: The trade policy approach is truly striking. If the Trump administration had announced several weeks ago that they planned to launch investigations over the next six to twelve months — giving them authority to increase tariffs on Europe unless it provided better market access for our tech firms and reduced its car tariffs — the reaction would have been different. If they had focused on targeted tariffs to re-shore specific sectors we care about, economists would debate the pros and cons, but we would have seen an orderly process with a reasonable chance of achieving policy success.

Even if there were economic costs, we wouldn’t be witnessing these wild market reactions. But that’s not the approach they’ve chosen. Instead, they seem determined to turn the world upside down overnight and then deal with the consequences.

What’s particularly notable is the rhetoric over the past week describing this as “medicine” the American economy needs to adjust to. Historically, political leaders talk about economic “medicine” when facing a massive debt crisis or when the economy is in free fall, requiring tough choices to turn things around. You rarely see leaders advocating shock therapy for an economy that’s actually growing reasonably well. Typically, adjustments are gradual. This represents a historically unprecedented approach to economic policymaking.

Jordan Schneider: That’s true, although some people in the administration legitimately believe there was either an existing crisis or an imminent one. Whether you or I agree, that perspective might be informing their approach.

You’re right about the hypothetical alternative — an Earth Two possibility where we had a sane, rational, logical approach to restructuring trade relationships. But that’s not the world we’re actually in. Any closing thoughts?

Kevin Xu: Not cooked.

Peter Harrell: I agree, not cooked. We’re going to get through this.

Matt Klein: We’re not done yet. For all the damage we’re doing to our international relationships, if the US was able to become friends with Vietnam by the 1990s, maybe it’ll take some time, but we can be friendly with Canada again.

Jordan Schneider: Alright, I guess that means some Canadian outtro music as an olive branch to our friends from the north.

I liked the are we cooked analogy. Since you seem to agree the U.S. is at least partially “cooked” I’m not clear how you “uncook” the damage to date. Assuming the destruction of US economic, legal, and political infrastructure stopped today, who would trust the US in the future? Other governments? Companies? Investors? Citizens? Try sending back that medium well steak at a restaurant next time and insist they turn it into tartare.

God, I hope we can pull through this together. Thank you for the informative and thoughtful conversation.