Is the NSC Unwell?

Historian John Gans discusses what ails America’s national security bureaucracy + ChinaTalk is hiring for AI analysts!

Heart attacks, prostate cancer, Jake Sullivan awake for a home invasion attempt at 4 a.m. because he was just up working on a random Tuesday night?

Is the national security bureaucracy in America, as one Cato blogpost recently put it, unwell?

To discuss, I have on today John Gans, a former Pentagon speechwriter, who’s had many, many other jobs in Washington. He is also the author of the fantastic White House Warriors, a history of the National Security Council.

We discuss:

Why the organizational design of the NSC leads to such crushing burdens for midlevel and senior staffers

Who gets to work at a place like this anyway

How POTUS’s time constraints impact decision-making

Why NSC’s historically are excellent at spotting problems but often overeager when crafting solutions

The pros and cons of the FDR, Kennedy, Nixon, and Trump “maverick model” of running the NSC compared to the Eisenhower and Obama vision of “regular order”

How seemingly prosaic technological innovations like track changes and video conferencing have dramatically changed national security policymaking

Before we get to the interview, I wanted to let you know that ChinaTalk is hiring for analysts looking to cover China and AI! Consider applying here.

Jordan Schneider: What is unwell about America’s national security bureaucracy?

John Gans: Well, there are obviously some outliers in the news recently. There’s the sad news that the Defense Secretary has been dealing with prostate cancer for months. General Eric Smith is the Commandant of the Marine Corps and is a former colleague of mine at the Pentagon. He had a heart attack and has since had surgery as publicly announced by the Marine Corps.

Is working in government bad for your health?

Heart attacks and prostate cancer probably aren't directly derived by the day job. There are plenty of people with both of these conditions who aren’t working in Washington or in the US national security bureaucracy.

That being said, I think there is a good question. I think every four years we see before and after pictures of presidents who looked spry, or at least relatively spry, when they get the job, and far less spry after four years and even worse after eight years.

I think that was pronounced with Barack Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton. This gig ages you. The same is true for those in the shadows. In fact, it might be worse.

They don't get the attention, great lighting, advanced teams, or staff making sure they have a peanut butter and jelly and whatever they were pumping Donald Trump with at the end of his term just to keep him upright after COVID and everything else.

These staff jobs are hard. They’re populated by people who drive themselves hard, and these are hard days. It takes a toll. As a system, it is not sustainable without a steady influx of new talent. There’s a reason national security advisers don’t do that job for 20 years.

The average tenure is short. There’s a reason these jobs go to younger people. The national security staff age has declined over about 80 years of the National Security Council because only certain people can do the job because your health is one thing.

Work-life balance is not even a discussion. If you have a family, a wife you’re taking care of, a mother to visit, if you have kids, you can’t do these jobs because the need is endless, the demands are endless, and the supply of time you have is limited.

But these people who are doing these jobs are tempted to sit there for twenty-three hours a day, and they’re in some ways rewarded for it.

Fresh Blood

Jordan Schneider: Let’s go through, step by step, the types of drivers that put someone in the situation where not just the National Security Advisor or the Commandant of Marines, but also the thirty-something with a significant other and a small child at home feels compelled to be working eighteen-, nineteen-, twenty-hour days.

We’ll start with this one because maybe it’s the simplest. It’s the sort of sense of importance and the type of person who wants to do this. It was interesting. I was struck by one of the characters in your book. He was at Kennedy’s inauguration, and Kennedy asked, “What can you do for this country?” You’re all inspired when you go into this.

We’re a long time away from that. We’ve had really ugly wars for the past twenty-five years. What type of person in the twenty-first century is drawn to these national security positions?

And if you could characterize the sense of why they’re in this game in the first place when there are so many reasons not to be from a compensation and work-life balance perspective. What’s the typical mindset of the person who ends up in one of these incredibly high-pressure roles?

John Gans: It’s a great question. I wrote this book on the National Security Council staff. There really isn’t a book about the staff, right? There are a few books about the advisors. I tried to just figure out what the staff was all about.

It was a really interesting experience. I would go out and talk to people, and I would say, these people, these are human beings, right? These people aren’t that different than you or me except, and this is the difference, right?

They’re flesh and blood. They generally have good educations. They come from enough of a foundation of family or financial support that they could attend a good college, maybe a post-grad degree, whatever.

That’s a difference-maker, the sense of humanity, but the difference between them and your average college graduate is, as you point out, that the number of people who were inspired to change their lives by the words of one politician in 1961 is shockingly high.

The number of the people I talked to of a certain age were like, “Well, I listened to John Kennedy, and I had to go work for the government.” It’s like they did. And they went and did things they regretted. Cases like one person who went to Vietnam and had a horrible experience and had a massive reaction and changed his life again — became much more of a dove. Another went on to put Marines in a position in Beirut where they were blown up at the airport in 1983.

They have made terrible decisions with this, but they are motivated to do this for some reason. I think there are not a lot of John Kennedys, and there are certainly not a lot of his inaugural addresses, right? But that still stands out as one of the best there is. But there are. Every generation there is something, a spark, a dog whistle that is heard by a certain number of people in the world who say, I have to go do this.

And, you know, for me, it was 9/11, and there’s a lot of people in my generation who are 9/11 people. For others, it was Ronald Reagan saying, “Tear down this wall.” And they hear it, and they go.

And there is enough of a supply of these folks who want to do this in their lives, and there is an endless demand.

Most people who want to do this, if they go to Washington and give it enough time, they will eventually show up in one of these jobs. It requires hitting a few marks, having a few educational marks, and having enough willingness to endure long days and low pay. And it’s not even that low of pay. You could do okay.

Certainly, if you’re in your twenties and thirties and wait it out and get to the end, you get the breaks that you require. It doesn’t require that many breaks to end up on the NSC staff. It doesn’t require any breaks to end up in a congressional office and do legislation that’s related to national security. It just doesn’t, you know?

That is the thing, right? Like, there are enough people here who need those young people that they’ll take them, and they just work there — and some just stick with it.

The difference between them is the same difference between your average politician and the President, right? Which is there’s enough of a fire burning in them to get to that top room, that they’ll endure anything to get there, and many of them do.

Pathways to Power

Jordan Schneider: It’s sort of interesting thinking about this in the context of US-China competition because it’s been this kind of weird, slow-burning thing for like 15 years, really. Like Alex Wang of Scale AI is the only prominent young person I’ve seen speaking with passion about US-China competition as a motivating force.

We haven’t had a 9/11, we haven’t had a JFK inaugural speech. I live very much in this world, and the folks who end up thinking about strategic technology competition, are just a very weird motley crew because there hasn’t quite been a crystallizing event or moment.

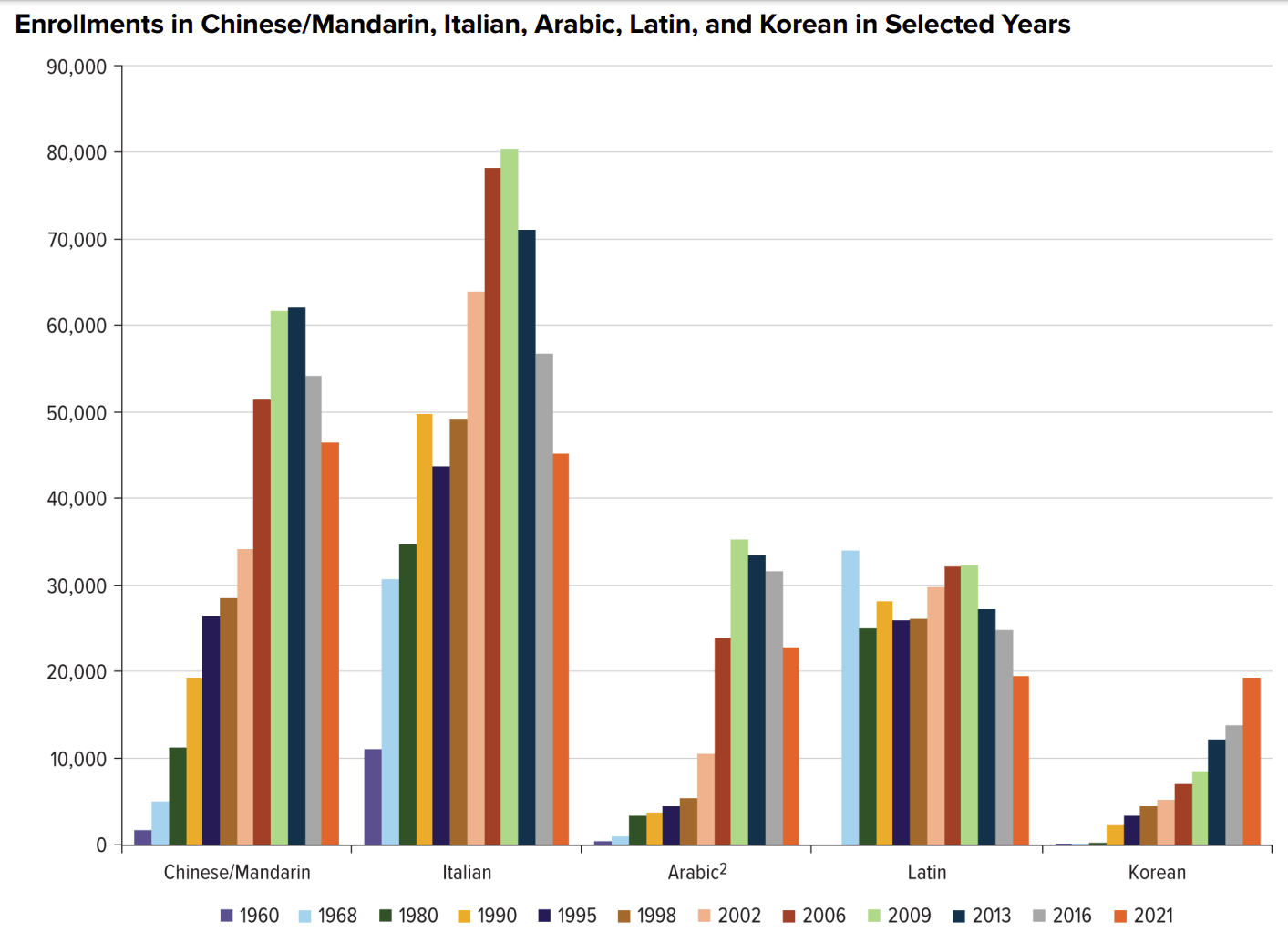

And by the way, way fewer people are studying Chinese way less than they even were five years ago.

John Gans: It is interesting, though, because I will say this, which is in some ways Washington isn’t that different from other towns where there’s a collection of talented people. It’s probably not that different from Silicon Valley where you have this world, and, we’re talking computers — I’m pointing to a computer, even though obviously that makes no sense to everybody listening to it for sure.

But, like, something about that world connects with them. They hear it, and they go, this is where I want to go, and they land there. Same with Hollywood. You watch a movie or a show, and something about it captures you, and you go out there and you say, “This is what I want to do.” In most cases, those places will allow you to do that. I think the China stuff is interesting because there have been different times in our history when China has done that.

Henry Luce and — oh, I’m sure the missionaries early in the century were inspired, I think. It’s interesting because I have friends who worked on Russia forever. That was not a hot topic either. I have a friend who works on Russia who has always worked on Russia, and it was like, how often was Russia cool over the last twenty to thirty years? He’s now at the Foreign Service, and he’s in his space. China was always, especially over the last twenty years, kind of like a niche — a big niche.

If you aspired for power, that was probably not where you ran over the last twenty years. It was a counter path because everybody wanting power ran to learn Arabic, serve in Iraq or Afghanistan, and check the boxes so they could get there fast.

But China was always one of those ones where it was also harder. Like, it’s harder. You know, it’s a lot easier to just go sign up and do a five-year tour, take a — hope you get lucky and don’t get hurt in Iraq or Afghanistan, and get security clearances to go in. Whereas learning Chinese and getting into that country, that’s a bigger, harder thing to do.

Jordan Schneider: I want to come back to this, the who’s in it and what’s motivating them because you have this ostensible ethos of the National Security Council where you have this concept of “Washington common law.”

These folks are like the air-traffic controllers. They’re getting all the dots in order, making sure the briefings are presented, and all the stakeholders are at the table. But you end up with the people who are on it being the youngest, the hungriest, the most capable.

They want to make their stamp in the universe, they want to be in the sequel to your book, right? And you don’t get a chapter in “White House Warriors” if all you’re doing is just kind of being a train conductor, right? There’s a really interesting tension there because I think that is another one of these drivers that leads people to these eighteen-to-nineteen-hour days, where they see themselves as absolutely mission critical.

I’m sure Jake Sullivan believed to the depth of his bones that if he was not working twenty-hour days during, you know, the pull-out in Afghanistan, fewer people would have gotten out. And if he wasn’t staying up all night talking to Zelensky and artillery manufacturers, there would be fewer shells that the Ukrainian military could use.

And part of that is — I’m sure part of that is true, but also, there’s this sense of, like, look, I’m at the pinnacle. Here’s my moment. Now’s my time to change the shape of world events. And if not me, who?

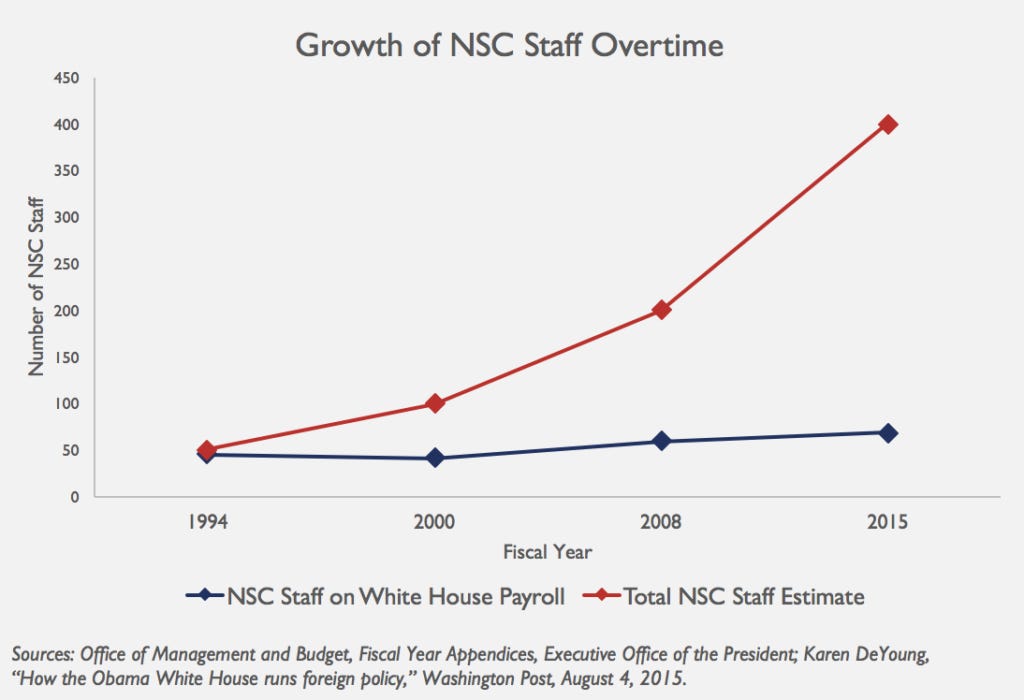

John Gans: The common law piece is … I use that term because the National Security Council was created in the 1940s. The National Security Act of 1947 is massive. The NSC staff was created with just one line of law. And there’s not, like, “The staff will be X, Y, and Z.” It is just like there will be a staff.

And what happened is that over sixty, seventy, and now almost eighty years, the NSC staff has evolved into being a creature of the President. All of these things were not certain. This was like up and off.

It’s just developed as a result of decisions that everybody’s reinforced and accepted. Nobody’s lost it. Nobody like, “I’m going to end this. I’m going to cut this off.” There are a few times when the people have tried that, but it was always like the President gets to do what he wants. He’s going to get a bunch of people here.

Both parties have sort of been okay with it, and it has existed. As a result, the demand signal is set. We need this number of people every day for a year. These billets exist. There’s just a desk that needs to be staffed, and somebody needs to do it. You get those decisions, you get those assignments.

Most people don’t get directly hired by the NSC. It’s not like they have a page that they, you know, career page where you can go and sign up and get there. Usually, you’ve served in the military, the Intelligence Community, or the diplomatic or Foreign Service.

And because there’s no money that’s really spent on the staff, its budget is actually not that much in terms of what’s appropriated. The NSC has always just taken people from these different baskets of paid-for money.

They’ve taken staff from the officer corps of the military, they’ve taken staff from Foreign Service, and from folks from the intelligence.

The way you get those jobs is because it’s perceived to be a mutual interest between whatever the parent agency is — the military, the Marines, or whoever, and the White House. Oh, it’s in both our interests to have these people serve here, so it’s kind of a plum assignment. Who gets your plum assignments? Your highflyers. Your highflyers then, get a two-year tour.

And those are basically what you get. You get a year, and then you can usually re-up for a second year, or you get two years flat out. That’s your place. I interviewed a lot of people for the job over the course of the book. And one of them said, “You’re like three steps from power.” It’s president, it’s then the national security advisor, the deputy national security advisor, whoever your boss is, and sometimes you’re closer.

And you sit there and say, how many times do you get to do that? You are in a position where you know you are probably the — you might not be the deepest expert on China, Afghanistan, AI, but for those two years, you have the opportunity to know more about that thing, about what’s happening, than anybody on the planet.

All the information goes to the center. They get to pull information from the embassy or wherever. And they have it all, and most of it gets sent to them. They don’t even have to fight for it because everybody wants to get their information to the White House.

You’re sitting here, you have two years, you have all this information, and you are a high-flyer. What are you going to do? And it’s funny. When I talked to people about this book, I was like, “You have an incentive to do something at that time.” And people would say, why?

And I said, in most cases, and in many cases, in almost every American war since World War II, the person that has said, “Yeah, we should do more,” has been a National Security Council staffer. And they have done that. And I’ve heard from staffers. I’ve been yelled at by staffers. And they said, “I didn’t do that.” And I’m like, “Okay, but you could have.” Or they would say, “I would never do that.” And I said, “Okay, we’ll see.”

I haven’t served on the staff, so everybody says, “Well, you didn’t serve on staff so you don’t know.” I’m, like, “Okay, well, I’ve interviewed dozens of staffers. I’ve read lots of stuff.” Like, you get to write a President — a memo to the President, tell him what you think he should do. The incentive is there.

“Go Big When We Can”

Jordan Schneider: You have this great kind of heuristic. I think you argued pretty compellingly over the course of looking at post-World War II, looking at the history of the NSC. They have all these information inputs and everyone’s trying to feed them the stuff. They actually do a better job of identifying the problems than a lot of other parts of the bureaucracy.

But because you’re on this short leash. I mean, you only have two years. You’re this high-flyer. You probably have a general bias towards action. You have this quote, “Go big when we can.” The sort of flashy, big solution where the president gets involved and solves your thing is this institutional bias of being this thirty-something who wants to make their dent in the universe. It’s for a good reason, but there is this kind of interesting savior complex that ends up manifesting in these roles.

John Gans: That’s a quote from an NSC staffer. That is literally a quote. The incentive is there. You’re sitting in the back seat of the car and you’re watching. And you don’t — you’re an NSC staffer. You are not an operator. Like, you are not doing the operation.

I looked at wars because it’s the high stakes. Like, it’s — to me, it’s like if they do it in war, they can do it anywhere. And, so, one of the things is that they are not the general on the ground who’s making decisions and sending guys and women out, and they’re not a diplomat in the room doing the negotiations. They’re not the operator, nor are they supposed to be.

When the NSC staff gets in operations, they tend to get in trouble for good reason because they aren’t operators. They don’t know the rules of the game. They’re not in that space.

They’re basically sitting in the back seat of the car. And arguably, they have a better view of what’s going on because they have more information coming to them. They’re not sitting in the theater, not sitting in the war, they’re not sitting in the headquarters in Baghdad, not sitting in the Green Zone.

They’re just sitting at 1600 Pennsylvania. They’re going to go home that night. They’re probably going to get better sleep and have better food. They’re going to see something better. They’re great at seeing the problem. They are great at saying, “Holy mackerel, we’re about to hit that car.” Or even more kindly, “Holy mackerel, we’re about to miss this turn.”

We’ve all been in a car when that’s happened. Do you jump up and grab the steering wheel? The challenge with it is that when you’re sitting at that desk, you feel some sense of the President’s responsibility, and it is the President’s responsibility. The President’s job is to grab the steering wheel or at least tell them to turn — order them to. And, so, these young people feel that sense of responsibility.

It’s a shared responsibility. It’s that principal-agent component, and they want to grab the steering wheel. And in many cases, they have. I take the long view on this, which is that American wars since World War II — there’s not a robust showing, I don’t think. There’s not really eighty years of statecraft that I think is going to hold up in the history books as a really fine effort.

Wars have a lot of problems. Most of them haven’t been great — lots of opportunity.

The NSC staff has great judgment for when something’s going wrong because they can see things. But they have very poor judgment on what to do because they’re not doing the things. It’s the classic operator’s dilemma.

When I’m cooking something, I’m in it, but somebody from outside the world can sit and say, “Oh man, you’re messing this up.” But when you’re in it, you don’t really get it, and you’re kind of like “I’ll figure it out.” They don’t have to have that problem.

But because they aren’t operating, they don’t have a sense of how to fix it. And they’ve done well in that prescription business.

Bureaucratic Bandwidth

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned presidents and one of the things that really stuck out to me was your story of the Obama administration in the first year, the decision whether or not to send more troops to Afghanistan.

You have this back and forth. Where are the generals? Boxing them in? But Obama, he’s really trying to do the regular order thing. He’s getting all the memos written, everyone’s at the table — this very deliberative discussion. He sees all the pros and cons of it.

The crazy thing for me was you have this line where he’s like, “Obama spent twenty-five hours on this.”

Like, this is an incredibly consequential decision. One of the most important decisions of his presidency. There are billions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of lives on the line … and twenty-five hours.

That’s just for the big one. With the ChinaTalk audience, we spend a lot of time thinking about national security and foreign policy. But this is, at most, 15%, 20% of the president’s time. And of that, your little issue is going to be some fraction of it.

It’s just kind of wild that we have this system — where there’s this executive who’s the one that ultimately has to make these decisions — just has so little bandwidth.

What are the sort of downstream implications of that dynamic, John?

John Gans: It’s not easy. I can sort of say it’s all been a subpar record over eighty years, but it’s not like it was easy. You can kind of get it. You’re sitting at a nice presidential library, Simi Valley for Reagan, or College Station for George H. W. Bush — whatever it is. You’re sitting at this library, at this nice desk, you’re going through their files.

You go through files from the first days of the Gulf crisis that became Desert Shield and then Desert Storm. You go through it, and the number of things going past one staffer’s desk is just truly shocking.

This is in the pre-email era. Today, it must just be constant. The amount of bad stuff stacking into your space is truly shocking. It’s very funny. I can’t actually tell if you think twenty-five hours is too much or too little. From the perspective of somebody who spent time with the President, like trying to understand the President, like, that’s a shocking amount of time. Like, it was a shocking number of hours they dedicated to it.

And that’s just the hours he sat at the Situation Room table. The amount of everybody else’s time was shocking, right? It kind of gets to it, but I think it also falls in the category of making national security decisions is kind of like planning a wedding. You can plan a wedding for tomorrow, or you can plan a wedding for three years, and the planning will take whatever time you give because you will just fill the time.

I think there’s a degree of this which is, like, you could have probably – and he could have probably made that call at hour three, and it probably would have turned out about the same way. I mean, I think what you do get is that the weirdness of the system is that it is a collection of parts that come together in a rather, you know, it was designed to, like, let’s just get everybody in the room, and we’ll think it through.

That was the concept. It’s not rocket science, but that was the concept, to get a bunch of smart people in the room. There’s a lot of staff work that goes into it. Then to accurately track what a bunch of smart people decide in the room and then implement it takes a lot of staff time. You have this whole operation built on trust.

This is the weirdest thing about the system because, you know, you could very easily see — and this has happened before. We’ve talked about who these people are — super ambitious, they’re driven to make history, they all have streams of information, they all want to have a say.

But the people at the National Security Council aren’t the only ones who want to have a say, right? Does the Secretary of Defense. You have all these super driven people who are super ambitious and are trying to make the most of their moments to make history and make their names, make their career.

The only way you can actually get them all to work together is if they trust each other.

You have to give a smart Secretary of Defense a chance to make his case over and over again. Because if you’re going to say no to him, the only way he’ll implement your decision is if he, at the end of the day, is if they genuinely believe you gave them a chance.

Now, like orders and all these sorts of things — that happens, and that’s what’s weird about that decision. At the end of the day, Barack Obama said, “This is an order,” and all the people like Bob Gates and everyone else were like, “That’s fucking weird.” Like, who gives an order, right? What happened was that the effort to build trust — to get everybody in the room and to give them a chance — actually led to a distrust that broke down.

So, Obama had to actually issue a direct order, which is why it was such a bizarre decision. You end up in a situation where this is all an effort to try and get the best out of smart people. There are examples of good decisions that were made, but it tends to lead to distrust more times than not.

The Biden administration is unique because they actually haven’t broken down into rivals and factions as aggressively as all others have. But they all have it. This one will eventually do that because they all do, because that’s human nature — the kind of people that end up in these jobs.

Jordan Schneider: Twenty-five hours, initially, seemed to me like not a lot of time. Two and a half days to make the biggest decision of my life. I’d want to know — about a topic I don’t really know a lot about, right? I would want more context and maybe a little more time to breathe.

But on the other hand, before that process, if everyone around the room could take odds on what Obama would do, I’m sure the betting favorite would have been, yeah, send in more troops, but not a ton more troops. The NSC as a trust-building institution that often is counterproductive is a really interesting dynamic.

Do real companies need trust-building organizations when the executive makes a decision? Is this something unique to the National Security bureaucracy or is America just this, like, unwieldy thing?

John Gans: I think, yes. You read the Steve Jobs book. He explains one of the reasons he was a terrible CEO the first time around was that he didn’t give a shit about what everybody said. He was just, like, if you can’t do it, get out.

And it led to, you know, eventually he got thrown out, right? And then he came around. It helped develop Tim Cook and other people. There’s a piece of this that is, I think, that everybody needs to do it. I mean, what makes national security different, right? I think, one, is financial incentives. There isn’t the “hey, you know, we’re all in this together, we can make a lot of money and, like, you’re going to be financially rewarded” dynamic. That’s one decisive factor.

I think it is also weird because, at the end of the day the National Security Council is kind of shielded. It’s like most people don’t know who the NSC staffer is working on China.

[ChinaTalk listeners will definitely know this was Kurt Campbell, our guest for the 300th episode!]

How many people in America know who Kurt Campbell is? Like, they don’t. I mean, Kurt Campbell’s on my dissertation. I love Kurt Campbell. He’s like a trip. He is amazing. I wish more people knew who he was. He’s smart, interesting, challenging, and charming. But how many people know who that is? Like, how many — I guarantee you most of the people who read my book were like, I have no idea who Meghan O’Sullivan is, but she influenced the biggest national security decision — certainly of the 20 years of her time — on both ends, right?

It’s fascinating. Most people don’t know who these people are. It’s not like you’re famous, right? War is also a very uniquely weird thing to deal with. National survival and war is very high stakes.

How do you get people to do this without shutting down? That’s a piece. And then the fourth thing I say is that everybody has a specific boss. Take Defense Department reports. Most of it is like uniformed military, and they will be there after the President leaves.

They could all sit on their hands for four years if they really wanted to. You know, same with — same is true of the Foreign Service. The same is true of the Intelligence Community, and the same is true of the rest of the federal bureaucracy.

And how do you get the best out of the so-called deep state?

Who’s going to be here the day after you get thrown out of office? You have to convince them to help.

That’s a very unique thing, because in theory, you could fire people in the private sector — like Steve Jobs. You have a hard time doing that to the US military.

You could maybe get rid of a chairman. But you can’t fire every one of them. Eventually, you’re going to need somebody to do the job. That’s the other piece. It is a very weird dynamic. The only basis for it — there’s only one person in the system who has any reason they can give an order. It’s because a bunch of people in America voted for them. Everybody else is hired by him. It’s a little weird. It’s a unique situation in that way.

Jordan Schneider: Governing by remote control is something that one of your subjects said. That was a concept I loved.

John Gans: Yeah, it was Condi Rice. She was like, “I’m the National Security Advisor. And if I want to get the US military to do something, I have to kind of hit this button and hope they do it.” That was her whole thing. I remember doing an interview with her, and I found her — I found all these characters to be pretty amazing, but she was very much more matter-of-fact. This is hard on a good day, right?

And a lot of times, remote control didn’t work for her. Don Rumsfeld didn’t let it work.

Paid subscribers get instant access to the second, much larger part of our convo with John Gans. We discuss:

The NSC’s role in America’s “forever wars.”

Roosevelt, Kennedy, Nixon, and Trump’s “maverick model” of running the NSC compared to the Eisenhower vision of “regular order”

How seemingly prosaic technological innovations like track changes and video conferencing have dramatically changed national security policymaking

How reading Shakespeare can improve the quality of our policy-making