Ishiba and a World Without Japan

ChinaTalk’s Tokyo correspondent Dylan Levi King with an essay on the future of the LDP and Japan.

The run-up to the election for the new leader of Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) had few electrifying moments, but one came when the princeling Koizumi Shinjiro dropped his radical, hopeless manifesto for changing the country. He torched the political elite, declaring that Japan was in decline — trapped in a terrible, terminal downward spiral that put the lives of Japanese people and the future of the country at risk…

His schemes to arrest that decline were not appealing to most LDP electors, but it was brave to say what most acknowledge privately: Japan has no future. Perhaps there will be jobs and distractions for its few young people as the archipelago transitions into a budget tourism destination. Maybe the increasing heat of the real estate market will allow the postwar generation to afford a tolerable senescence. Maybe the money will still come to support the American bases. But, most relevant to this readership, Japan will cease to matter geopolitically.

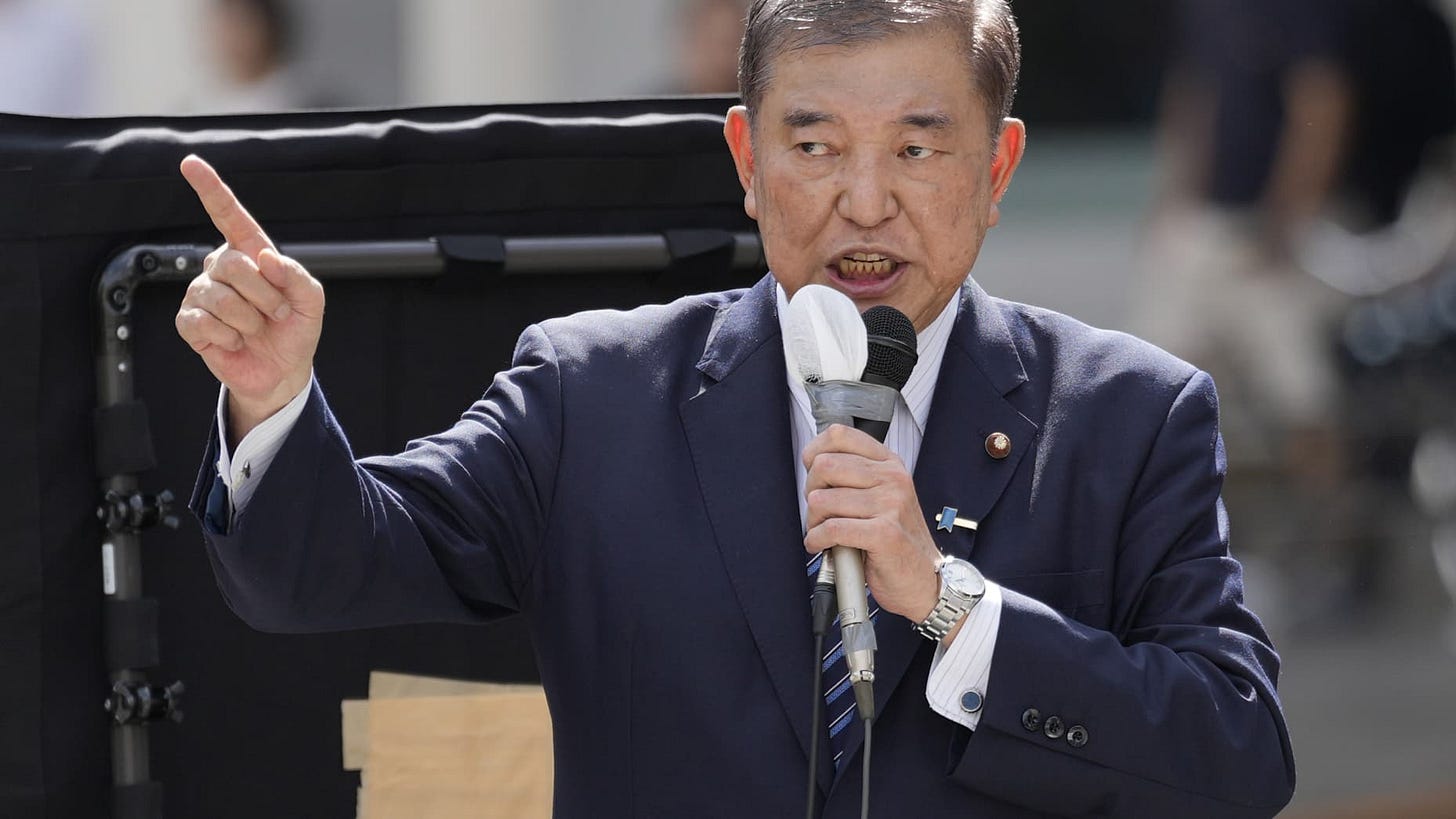

On September 27, Koizumi came in third behind Ishiba Shigeru, the America-skeptical ICBM otaku, and Takaichi Sanae, the ultranationalist Abe Shinzo disciple. A runoff spit out Ishiba as the new leader of the LDP and Prime Minister–designate.

This is how it was always going to happen, despite Koizumi’s apocalyptic warning.

Kishida Fumio, the current Prime Minister and chief of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), was unable to overcome catastrophically low approval numbers, a slack economy, and (by American standards pretty tame) scandal. He announced last month that he would move aside for a replacement, and the usual crowd lined up to take a shot at his posts. We had seen them all before: the would-be Iron Lady (Takaichi Sanae), the Georgetown-educated internationalist (Kono Taro), the old-school bureaucrat (Hayashi Yoshimasa), the princeling (Koizumi Shinjiro), the financial whiz (Kobayashi Takayuki), the military nerd (Ishiba Shigeru)...

A bit of LDP Kremlinology, a scan of opinion polls, and a survey of newspaper columns made it clear that the frontrunner would be perennial also-ran Ishiba, with Takaichi taking up the lead, and Koizumi and Kobayashi tolerated as sideshows. The two younger men — Koizumi and Kobayashi — made waves early on, with bold proposals for economic reform (Kobayashi’s pro-business platform) and constitutional revision (Koizumi wanted to put the clause outlawing war to a referendum), but they lacked support from the éminences grises of the LDP. Takaichi, the most hawkish of the candidates, tried to soften her image ahead of the showdown with Ishiba, but was tripped up by her allegiance to other former Abe acolytes that have been caught up in the recent political financing scandal.

And so, Ishiba was chosen almost by default. Even though Ishiba’s record in the House of Representatives and Cabinet was not electrifying, and even though his national public support has always been anemic — he is competent. He won’t embarrass himself. He will be designated the Prime Minister on October 1.

Ishiba will undoubtedly drag the LDP across the line in the snap election he has called for late October. Although his party has been internally fractured by factional battles and scandals, the elements of the opposition that could stand against the LDP are once again in complete disarray (conservative Noda Yoshihiko’s election to the leadership of the Constitutional Democratic Party a few days earlier broke their temporary pact with the Japan Communist Party); the LDP’s current and potential government partners — the regional technocratic parties, as well as the Soka Gakkai–backed Komeito — are still content to offer their support.

For anyone that believes in Koizumi’s warning of terminal decline, the election of Ishiba might be slightly disturbing. It’s not that he is an incompetent leader, nor that he is particularly corrupt — but rather that he is unlikely to be able to actually do anything.

The ultra-stable state of Japanese politics is precisely the problem. It has become increasingly difficult to push the country in a new direction.

Ishiba is destined to become another in a long line of interchangeable helmsmen, steering Japan into increasing geopolitical marginalization.

Ishiba will be another Kishida, at best. We will have another “compromiser,” as Kenji Kushida termed Kishida. Many more uncharismatic caretakers will shuffle through the revolving door. Like Suga and Kishida, Ishiba will keep the machine ticking along, without seeking — or managing — to create policy with their individual stamps on it.

Even though Kishida arrived in office with a respectable mandate, modest goals, factional support, and plenty of good will, he was forced to water down his New Capitalism scheme, which was intended to get the economy back online. In the end, the modest reforms that he did force through earned guarded praise from international observers, but he failed to snap the long-term malaise, growing inequality, and the short-term pain brought on by inflation, frozen wage growth, and the weak yen.

As William Pesek pointed out in Barron’s, eyeing Kishida’s replacements, “there’s not a single known economic reformer.” That is true of Ishiba, certainly. He has signaled with familiar language his desire to raise wages and increase consumption, but it is clear that radical reform is not on the horizon.

Increasing poverty, or at least inequality and a stagnant economy, are not minor inconveniences, even to geopolitical partners.

And so, perhaps, as American leaders as far back as Ronald Reagan have demanded, Japan will get serious about funding its own defense, but the cash and political will required is not forthcoming.

The record of Abe is important here: he was a man with a mandate, who remained in power longer than any postwar Prime Minister — but he failed in his pledge to roll back Article Nine, succeeding only in securing a shaky legal ruling to follow the United States into regional conflicts. Those that came after him have struggled, and the same pattern will continue. Kishida fought for more defense spending, but it still remains unclear where the money to pay for it will actually come from, nor what strategic benefits will be acquired.

Ishiba might have once expressed bold plans to take Japan out from under America’s nuclear umbrella, but, in truth, he will be a caretaker Prime Minister with a shaky majority — and that is not a strong position from which to defy public opinion and go against the peace commitments of his coalition partners (the Soka Gakkai–linked Komeito are sometimes a peculiar partner to the LDP)...

Nobody will press Ishiba to act rashly. The geopolitical realities of the Second Cold War, as well as the sort of warfare we can expect, no longer call for an unsinkable aircraft carrier, as another LDP man termed Japan in 1983, during a desperate visit to Washington. For the conceivable future, there’s not much reason to expect the theater-wide conflict imagined in the simulations (to draw Japan in, these rely on fantastic strikes on Okinawa). Proxy wars and insurgencies on China’s margins could involve Japan’s espionage agencies, but probably not the Self-Defense Forces.

The American leadership can deal with this.

If we could imagine the situation as seen from Zhongnanhai, they might sum it up this way: the Japanese will buy Tomahawks, tolerate bases in Okinawa, and put increasingly absurd strings of zeroes behind their defense budget, and talk about reshoring — but their military capabilities, willingness to fight, as well as their ability to wage economic warfare, are limited. Maybe we can sell them electric cars, eventually.

And so, exports to and imports from China continue to increase. The political and industrial elite of Japan, despite embracing American directives on China, cannot lean too far in one direction.

The possibility of Japan distancing itself from American-led security initiatives and turning to closer ties with China seems just as unlikely — for many of the same reasons. To rebalance away from the United States would require thorough reform and tactful planning of matters as diverse as trade policy, food security, and defense.

Ishiba is not a renowned statesmen. Pro-China smears against him have been picked up by mainstream outlets beyond Japan, but it is mostly fantasy. The fact that he was in Taiwan when he announced his run for the LDP leadership is not a coincidence. Rather than being enthusiastic about the possibilities of the Sino-Japanese relationship, he is mildly unenthusiastic about perpetually hitching Japan to American fortunes, skeptical of the nuclear umbrella, and believes in securing Japanese independence by restoring her military might. It is illuminating that he is alone among LDP heavyweights in advocating normalizing relations with North Korea, while also suggesting first-strike capability against Pyongyang is crucial.

He will also be forced to tackle the China relationship without the benefit of the eighty-five-year-old Nikai Toshihiro, long-term LDP Secretary-General and stalwart protector of a Sino-Japanese relationship, who has become vital to the local economy. Chinese domestic observers celebrated his visit to Beijing earlier this month as a sign of stability, but an editorial in the Asahi Shimbun noted that it is probably the end of an era.

As far as the rest of the world is concerned, the Japanese political system will tick along, without causing undue distress to the United States, nor beyond the level of diplomatic dustups, to friends-of-friends, like South Korea and the Philippines.

Ishiba is unlikely to arrest — or even acknowledge — the decline that Koizumi spoke about. If Ishiba oversees the decline reasonably, he will continue to hold power; if he fails, another LDP veteran will be shuffled into his office. And none of it matters.

Dylan also writes a fantastically eccentric Substack. My favorite entry is his one on eating Chinese noodles in Tokyo. See below for his meditation on Ishiba.

It was a Friday, the day Abe Shinzo was shot. I was on my way back from the beach, I think. I remember watching a screen in the train paused on the shot of the ambulance waiting for the helicopter to arrive and carry the Prime Minister’s body away. There was no official announcement, but the tone made it clear that he was already dead. I almost wept, thinking of his widow, and thinking of the man that I had seen in the quarantine video, playing with his dog in a modest kitchen. The screen flipped to the next news story, or to an advertisement. I looked around the car. I don’t know why I imagined some public expressions of grief or distress from the commuters, but there were none. ▭ I wanted it to mean something. That night, I went to a ■■■■■ ■■■, and tried to make conversation about it with ■■■ ■■■■ behind the counter. She changed the topic. I tried the same tactic with a ■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■, when I went to pick up ■■ ■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■■■, but I was brushed off in the same way. ▭ But it meant nothing. ▭ The best I got was from two kids from Okinawa in the square outside Koenji Station, who were at least willing to celebrate political violence. ▣ I took a train to Nara a few months later. All I found were tattered sheets of A4, bearing warnings against laying flowers, pasted up where the Prime Minister had collapsed. There was nothing else to see. I walked in the dead malls around the station. I walked through the state housing projects at the other exit. ▣ This is a good thing about Japan: the sort of political discussion that animates American society is rare in Japanese life. I am talking about my neighbors. They fall into three groups: there are those that do not apparently care at all about political affairs, there are those that are engaged with local committees, but mostly as a channel to air grievances against neighbors, and there are those that are actively involved in politics and never talk about it in social settings. Most of the latter group are members of the Communist Party. I can spot them among the group that gathers outside the Metro station every second afternoon to shout for denuclearization and living wages. ▣ This makes me think of an acquaintance, an older woman that I talk to every now and then because our ■■■■ ■■ ■■ ■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■. I learned that she attends any political rally that is held in our neighborhood. She goes to greet the politicians running for office, and even calls up encouragement to them, as they speak from the roofs of vans. She will attend events for any candidates that arrive, regardless of affiliation. Her own politics do not align with any of them. She is rare: she likes to talk about politics in the same way that Americans do. She asked me earnestly one day whether or not I thought vaccines might contain 5G transmitters. When I reacted with enough warmth, she began to inform me about various Zionist and Korean conspiracies against her country. She doesn’t vote. She doesn’t care. Nothing matters. ▣ I am being dismissive, I know, of this woman. I was too dismissive of the old Communists I mentioned before. I was too dismissive of the young men from Okinawa that fantasized about even more shocking acts of terrorism. By not even mentioning them, I am being too dismissive of the young people that are involved in ongoing struggles. I am talking about the minority; I don’t understand them. ▣ The lack of interest makes sense, generally. Populism is taboo. Charisma is closely monitored. Voter turnout will never improve. It is fine that a Prime Minister can be chosen only because he has failed enough times, and everyone feels pity for him. ▣

Check out more from Dylan here:

Takaichi is not ultranationalist. These cheap platitudes are so boring.